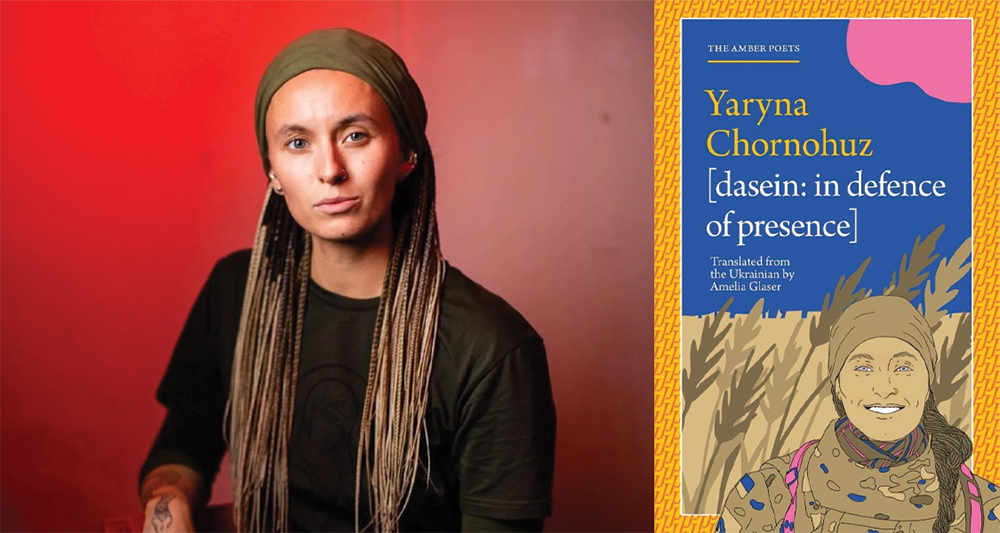

[dasein: defence of presence] by Yaryna Chornohuz, translated from the Ukrainian by Amelia Glaser, Jantar Publishing, 2025

In 1922, the Spanish philosopher, essayist, and poet George Santayana wrote: ‘Only the dead have seen the end of war.’ Though initially penned when reflecting on the impact of World War I, his words would remain just as pertinent a century later. With this sombre message ringing strong as horrors continue to unfold in Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, Jantar Publishing brought us a transfixing collection in late 2025: [dasein: defence of presence], written by widely lauded poet and member of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, Yaryna Chornohuz, and translated by Amelia Glaser. Originally published in Ukrainian in 2023 and drawing on Heidegger’s principle of Dasein (‘being-there’ / ‘being-in-the-world’), Chornohuz writes of her experiences and reflections from the frontlines with harrowing lyricism, exploring themes of existence, mortality, and grief.

In Being and Time, Heidegger defines Dasein as ‘this entity which each of us is himself and which includes inquiring as one of the possibilities of its Being’—in other words, this philosophical principle is distinct from a mere essence or detached existence, but rather stresses the importance of active engagement with one’s environment and circumstances. This significance of inter-personal and inter-situational interaction challenges humanist interpretations, in which people are viewed through the lens of a static Cartesian subject. Further still, this involvement, being so consciously instigated, thereby inherently necessitates a confrontation with one’s own mortality as much as their personhood.

Chornohuz, who had previously dedicated herself to seven years of study in philology, Ukrainian literature, and philosophy, and used to work as a volunteer paramedic, enlisted full-time in the Ukrainian Armed Forces in 2020 after her partner, Mykola Sorochuk, was killed in action. [dasein] therefore traces Chornohuz’s attempted reconciliations with her partner’s death, as well as her reflections on her own mortality—both a consequence of her loss and an inevitable symptom of serving in the war. Her choice to reference Dasein in the collection’s title (in Ukrainian as [dasein: оборона присутності]) signals her intentional participation in the discussion of being and all it entails: a lifelong pursuit of expressing authentic truth, or, as Heidegger put it, ‘the most primordial phenomenon of truth’ (‘das ursprünglichste Phänomen der Wahrheit erreicht’).

If in The Unwomanly Face of War, Nobel Laureate Svetlana Alexievich asserts that she must write ‘the truth about life and death in general, not only the truth about war’, what does [dasein: defence of presence] tell us about Yaryna Chornohuz’s truth? Firstly, as Hugh Roberts states in the collection’s foreword, this war is an existential one. By consequence, a biting tension suffuses Chornohuz’s poetry: the recognition that war as a concept—while ideologically abhorrent (‘the / puppeteer of wars knows full well that the reapers of / war’s fruits are themselves fruits of war’)—is utterly indispensable in ensuring Ukraine’s safety, history, culture, language, future, essence, and existence. In this way, defending the country is no longer a choice; it is an incontrovertible duty and unavoidable reality.

Chornohuz’s exhortation in defence of Ukraine’s presence is at once melancholy yet resolute. Her dedicatory epigraphs are simultaneously assured and indicative of the emotional intensity of this collection. ‘To my grandfather Oleh Chornohuz’ recalls the prominent Ukrainian satirical writer who passed away in early 2023, while her closing statement—‘To all those who died in the battle for Ukraine’s continued resistance to russia’s genocidal war 2014-2023, which continues to this day’—pulls her reader into the desolate reality of Ukrainians.

Everything about [dasein]’s poems contributes to their lasting, altering effect. As indicated by the stylised use of punctuation in the collection’s title, the title of each poem is also closed off by square brackets. Indeed, the book’s first composition even bears the punctuation mark’s name: ‘[square brackets]’. Typically used in quotations to denote an addition or change to the original, as well as a clarification supplementary to the text, the use of square brackets throughout [dasein] is inescapable to the reader’s eye, with the question surrounding its possible interpretations persisting throughout the collection.

The ellipsis is also granted its own poem. Ellipses have long been used in writing to build suspense, to denote the tapering off of thought, and perhaps even the burgeoning hope of something yet to come—but Chornohuz sharply eliminates ambiguity as to its meaning:

when I look at the bracketed ellipses

that delineate your life

surrendered to the light

Here, the whispers of a future which we might otherwise associate with ellipses are smothered; any potential is cut short and contained within the prison of the square brackets. The expanse of a life is constricted, while its depth and complexity are rendered reductive and perfunctory, represented by three small, consecutive dots alone: a tension between the micro- and macrocosm. The opening and closing lines of the poem, ‘how quietly you left…’, therefore categorically eschew any indeterminancy as Chornohuz’s cycle of reflection returns to the same point from which she had departed.

In ‘[the ones who will die fighting]’, the opening stanza includes the lines ‘in war no one ever resolves to die fighting / (that’s just a silly literary notion)’, echoing sentiments from other prominent examples of war poetry; Wilfred Owen’s declaration that ‘Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori’ is ‘the old Lie’ springs to mind. Instead of niceties, she opts for bracing honesty—the same kind that she states the world attained ‘when it named all the names’, listing how ‘Serhiy lost Yana / Yuliya lost Ilya / Inna lost Ihor/ Halyna lost Mykola’ in ‘[the Creation of the World, which they don’t remember]’. This continues in ‘[Ukrainian danse macabre]’, where she once more humanises and immortalises the deaths of the individuals behind the statistics with her pen:

. . . in this country it’s precisely those

who can imagine in their youth what it’s like to make love when they’re old

who won’t get to grow old

who will certainly die young near the village of Zholobok in greater Luhansk or Donbas

from a shell aimed at the dugout

from a detonated grenade

from a sniper’s shot

An especially haunting poem is ‘[left under occupation 2]’, the second in a poetic triptych, with the emotive lines:

“but if you were alive I’d embrace you.”

“and if you were alive you’d hear my voice over the ripples of the Donets”

I keep on walking behind you in single file

as though on the next recon mission

The poignant image of our speaker keeping close behind the ghost of her departed is reminiscent of Orpheus and Eurydice; Chornohuz is our Orpheus—our singer, our poet, our prophet—forever a single step behind her love, who remains inaccessible behind the veil separating the living from the dead. The poet’s evocation of this liminality, as well as the depth of her loss, is a mere glimpse into the power Chornohuz wields over her language and expression throughout [dasein].

Glaser’s English rendering is sublime. From the choice to maintain Chornohuz’s anthropomorphisms as gendered (‘we’ll invite Death over, / to warm herself by our fire’) to retaining the poet’s de-capitalisation of ‘russia’, Glaser effortlessly transmits this collection’s defiance and pathos. A particularly remarkable translation comes in ‘[a spot too red]’:

голос не гасне якщо вміє бути

but a voice won’t die if it knows how to be

The Ukrainian’s voiceless glottal fricatives of ‘г’s and sibilants are mimetic of a voice fighting its way out of the throat and asserting its presence, quietly but with steadfast strength—and though positioned differently within the line, these same sounds prevail in the English too.

[dasein: defence of presence] was always sure to attain and epitomise Heideggerian authentic truth because, as Chornohuz herself affirmed in an interview, ‘поезія ловит моменти істоні завжди’: ‘poetry always captures moments of truth’. The irrefutability of her writing and her truth is that it is fundamentally born of pain, which she proclaims is the only thing that does not lie ‘in [Ukraine]’. To return to Alexievich, not only is ‘pain . . . proof of past life’, it is also proof of love and therefore of legacy. After a person’s death, the pain you feel is the ultimate testament to everything you shared and experienced together. The pain is the indelible vestige that time will not heal and memory will not erase; it is the wound that refuses to scar. Thus, not only does Chornohuz ‘place herself . . . in a poetic lineage of transgenerational trauma’, as Hugh Roberts states, the pain and trauma that engendered this collection also keeps the departed alive on the page. As a reader, it is an honour to partake in their remembrance.

Such is the lot of the Ukrainian poet: ‘to eternally weep elegies over / freshly dug graves / and also over ancient ones’. Yaryna Chornohuz has undoubtedly entered into the canon of Ukrainian literature, and one can only hope that Glaser’s English translation can help this powerful voice carry farther still. While Virgil opened his Aeneid by singing of arms and the man, Chornohuz ends her opening poem with no less striking an image:

I want to sing, while I can,

of freedom

Sophie Benbelaid is a Senior Assistant Editor for Asymptote based in London and holds two degrees in French and Russian Literature from the University of Oxford. She was acknowledged for her contributions to Robert Chandler’s translation of Other Worlds: Peasants, Pilgrims, Spirits and Saints by Teffi, and was a finalist in the International Translation Contest “Writers of the Silver Age about War” held by The Library for Foreign Literature and the Institute for Literary Translation. Having previously worked as a translation intern with the Institute for Literary Translation, she is an aspiring literary translator and hopes to publish her work in the near future. For now, you can read her writing on her Substack.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: