Dizzying, furious, scathing, and absurdist—artist and writer Sener Ozemen’s The Competition of Unfinished Stories is a testament to an identity, region, and language under siege. The novel, with its many layered narratives, confronts the Turkish state’s enduring violence against its Kurdish minority, illustrating the psychic and physical fractures of oppression with intellectual complexity and emotional clarity. In attempting to disentangle the knot of selfhood from a merciless assimilating power and a growingly fragmentary everyday existence, Ozmen builds the architecture of fiction to its most veering heights, capturing all the threads of reality’s illusions, and thus resulting in one of contemporary fiction’s most vivid portraits of psychological dissolution—that which still never turns away from the need to express its truths.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

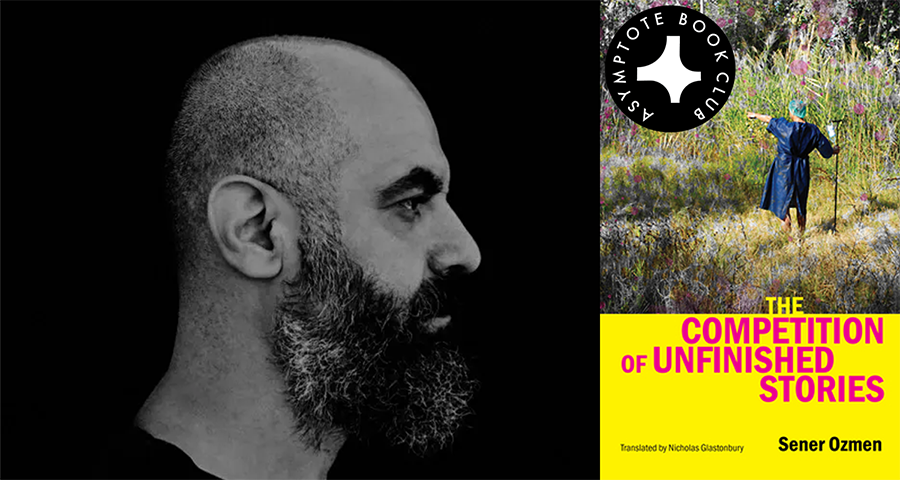

The Competition of Unfinished Stories by Sener Ozmen, translated from the Kurdish by Nicholas Glastonbury, Sandorf Passage, 2025

In her book Immemorial, Lauren Markham notes that “the feeling of grieving something that isn’t yet gone, and whose disappearance isn’t fully certain . . . is an eerie, off-putting one.” This liminality and its disquieting effect are what animates Sener Ozmen’s The Competition of Unfinished Stories, deftly translated by Nicholas Glastonbury. This is not only the author’s debut in the Anglosphere, but one of the first works written in Kurdish’s northern Kurmancî dialect to receive an English translation.

Ozmen is a prolific Kurdish writer and multimedia visual artist, the author of numerous books of poetry, novels and short stories, criticism, and artist books. Across his written oeuvre and artistic practice, he has drawn attention to both the urgency and difficulty of speaking from a position of marginalization; The Competition of Unfinished Stories, originally published in Kurmancî as Pêşbaziya Çîrokên Neqediyayî in 2010 and translated into Turkish as Kifayetsiz Hikâyeler Müsabakası in 2015, follows in this spirit. The novel dramatizes—in a challenging and disorienting way—that the stories one tells are always co-authored and situated, demonstrating the interrelatedness and imbrication of the self. As Judith Butler observes in Giving an Account of Oneself, “When the ‘I’ seeks to give an account of itself, an account that must include the conditions of its own emergence, it must, as a matter of necessity, become a social theorist.”

In the case of Ozmen’s novel, attempts at storytelling reveal a splitting of the self and a rupturing of identity under an oppressive and suppressive regime. Kurdish history in Turkey is fraught and violent, with the advocation for Kurdish rights and language having become synonymous with terrorism, resulting in ongoing clashes between Turkish soldiers and P.K.K. militants for almost fifty years. Since the establishment of the republic, there has been a sustained effort to eradicate Kurdish identity, language, and culture: a process of “Turkification.” People have been sued, fined, or imprisoned for minor and seemingly inoffensive uses of the Kurdish language—such as usage of the letters W, X, and Q, which are part of the Kurdish but not Turkish alphabet. Turkish law forbids the acknowledgement of Kurdish as a distinct ethnic group, and for almost a decade in the early 80s to 90s, it was illegal to speak Kurdish in public. The millions of Kurds living in Turkey were commonly referred to as “Mountain Turks.” For Kurdish people, this is not just a campaign of marginalization, but of active erasure, linguicide, and radical assimilation.

To capture the precarious existential condition of Kurds, Ozmen has crafted a book that resembles a piece of performance art, defying novelistic conventions and incorporating numerous references to western philosophy and critical theory (Deleuze, Althusser) as well as pop culture (Neil Armstrong, Eurovision). The protagonist, Sertac Karan, is a Kurdish atheist who finds himself teaching at a conservative, religious Turkish school. In the first part of the book, subtitled “Faith,” Sertac’s students rebuke him for failing to follow the appropriate scripts: for example, forgetting to say “Peace be upon him” after invoking the prophet. Having been abandoned by his wife and fed up with his job, he is alienated from “the Community of Believers” at the school. As he sits in the classroom, waiting for the day to conclude, meditating on his unwillingness to rock the boat, his mind drifts back to “an unfinished story” that he lets take over. The book then alternates between the perspective of Sertac the teacher, written in the present tense, and the stories he begins but never completes, all of which resemble his own memories, plunging increasingly into absurdism and flights of fancy.

The preface to the novel is narrated by a woman named Merasîm, who steals Sertac from her older sister Yasemîn. She appears in his narrative as a domineering wife, and in the stories as Sertac’s first girlfriend and heartbreak. Unlike Sertac, Merasîm is given a first-person perspective, and as such, the book initially seems to be her story rather than his. It begins with the line, “The first time I saw him was in October 1998”—and we don’t learn “his” name until the second paragraph. From the outset, the reader’s experience of Sertac is mediated through someone else’s story, a framing device that becomes unsettling when we learn about one of Sertac’s recurring dreams: that Merasîm becomes a famous and award-winning author using his stories, erasing him as the author.

Through these themes of obviation and subject-object reversal, The Competition of Unfinished Stories offers a sustained commentary on Kurdish identity within the Turkish nation state. Merasîm confesses that Yasemîn habitually condemns her for eliding Kurdishness by referring to a mythical place called “The Southeast” instead of Kurdistan, and even though their mother is Kurdish, their father is an émigré and insists, “‘Biz Türküz, kızım’” (“We’re Turks, my daughter”). This erasure of their mother’s identity, and her refusal to defend it, upsets Yasemîn to no end, but seems to have little impact on Merasîm—a cavalier attitude that affects Sertac as well. Their first fight occurs when she mispronounces his name: “As far as he was concerned, there was a mortal difference between ‘c’ and ‘ç’ that I couldn’t possibly understand. . .” This scene recalls a fight Sertac’s father had with the birth clerk about the diacritical mark on his newborn son’s name: Sertac has inherited an intergenerational struggle over language.

Spivak’s famous question “can the subaltern speak?” seems to haunt the novel. Sertac tries to speak, but does so always indirectly, through his unresolved stories. Along the way, a polyphony of narrative voices create dissonance rather than harmony, always threatening to hijack the narrative. A constant refrain throughout the book is the assertion, “This story was his story.” It is an attempt to assign authorial control to Sertac, but the narratives continuously slip through his grasp. The book thus offers a commentary on the complexity of self-narrativization when one is determined by what Maldonado-Torres calls “the coloniality of being”; Sertac is a victim of the epistemic violence perpetrated by the Turkish state, and his inability to finish a story is symptomatic to his denial of his homeland, identity, and history. From a Turkish perspective, there is no Kurdistan; there never has been, there never will be. Ozmen’s novel meditates on what this effacement does to someone’s subjectivity.

Asterisks appear after certain words or names, leading to notes written by a fictional translator, which are themselves biting, irreverent, and overtly political. In a discussion of the word “Sheikh,” the note regretfully notes that the English word is transmitted from Arabic rather than Kurdish: “. . . this word . . . occupies this text the way that Kurdistan is occupied by Arab countries: unwillingly, and with a tyranny only surpassed by the Republic of Turkey.” Elsewhere, in relation to the name Ataturk, the translator notes the missing umlaut in his name, because “no such letter exists in the Kurdish language,” and goes on to justify this omission given that “Ataturk is the father of Turkey’s language policy”—a policy that has aimed to suppress any traces of Kurdish: “. . . we should feel comfortable withholding from him the courtesy of his umlaut.” It isn’t accidental that these acts of subversion and reclamation take place in the margins of the text. Reflecting on the dynamic between Sertac and his colleagues, the narrator mentions that it is convivial until the invocation of “the Kurdish question,” which is glossed in footnote as: “A truly dazzling euphemism for what happens when the Kurds resist their wholesale erasure, no matter violent or nonviolent. As a still more famous question asks: What is to be done? The ‘Kurdish question’ is a question to which the only acceptable answer, at least to the state of Turkey, is to stop with all this Kurdistan shit.”

Atatürk, and the precedent of Turkish nationalism he set, loom large over the novel, which tellingly begins in Mêrsîn, where there is a museum for the founder’s house. In the stories that trace Sertac’s childhood, his teachers command him and his peers to “shed those tears for Ataturk” on the anniversary of his death. As he grows up, beset by contradictions, he eventually falls into the rituals of Turkish nationalism, publicly proclaiming the slogan “How happy is he who calls himself a Turk,” but always privately reflecting on his profound unhappiness. At home, his mother insists “We’re Turks,” but does so in Kurdish. These tensions lead Sertac to realize that he is part of an ongoing project of assimilation: “He wasn’t one of them, it seemed, or he was one of them but not one of them enough; he had so many shortcomings, but eventually, ever so slowly, those shortcomings would be allayed, ever so slowly.” As more Kurdish revolutionaries, including his beloved uncle, begin to disappear, Sertac discovers fear, a force that would go on to permeate his life. His paranoia increases to the point where he doesn’t leave the house, afraid of what might be done to someone suspected of dissent. The possibility and normalization of torture and punishment cause him endless anxiety; he brings his ID even to the bathroom.

Meanwhile, the apathy toward “the Kurdish question” reaches a boiling point for Sertac the schoolteacher. In one crucial scene, he confronts a group of young women accepting donations for Palestinians, acknowledging the “incomparable cruelty” they’ve suffered but angrily bringing up “something not quite as far away”: Saddam Hussein’s mass murder of Muslim Kurds in Iraq. Sertac laments a lack of solidarity and the hypocrisy of hierarchizing the oppressed, demanding, “How many Arab states, including Palestine, raised their voices in objection to this massacre . . .? Let me tell you: not a single one. Why? Yes, why? Is God not One? Was God not One then? I will never entrust my faith to a God who is Arab!” As his sense of betrayal grows, his relationship to religion too is strained, and he speaks of the Qur’an: “I don’t even know what you contain! And I don’t get how you can fuck with me and my soul so much when I don’t even believe in you!” Recalling a Zarathustra-in-reverse madman from his childhood who affirmed God’s greatness rather than proclaimed his death, Sertac finds himself adopting the same position.

This religious awakening coincides with Sertac’s psychological break, as the writer and the character begin to blur dangerously. His name begins to take on epithets such as “Sertac aka His-very-own-accomplice Sertac,” splitting his sense of self, and he laments the futility of his compositions: “He realized he would never, never, never finish his story. He finally realized that this life of his, this life devoid of any meaning at all, only emerged as the outcome of these unfinished stories he never, absolutely never, ever, experienced himself—he was the product of one of those unfinished stories.” In an existentially fraught catch-22, Sertac finds that he has no reality outside of his stories, and their unfinished nature can only mirror his own lack of coherence and completeness.

Paraphrasing Foucault, Butler writes about how government can limit possibilities of selfhood: “. . . what I can ‘be,’ quite literally, is constrained in advance by a regime of truth that decides what will and will not be a recognizable form of being.” In a perversion of the Delphic imperative toward self-knowledge, Sertac begins to understand the effects of oppressive power: “I know myself, I alone know ‘what’ I am. No, I was never ‘somebody.’ They kept me from becoming somebody; they didn’t even let me see myself as a normal person. . . . I am an unintended outcome, the outcome of experiments that could only have been conducted in a colonial laboratory.” The crushing realization that undoes Sertac’s sanity is that he is a creation of the Turkish state, that he has no autonomy or authenticity as a subject. What seem to be accounts of his past are really just made-up stories, as memory itself has become a site of power and control, a narrative that can be thrown into doubt. The limitless scope of the imagination offers no redemptive power or escape; it only serves to further imprison him.

In the next two parts—“Doubt” and “Signifier”—the schizophrenic paranoia that develops under repression is on full display. Linear plot recedes, and stories proliferate in a kind of surrealist fever dream. First we find Sertac as a reluctant revolutionary who tells fictional tales to his fictional therapist, Dr. Sarîn Zavaryan. In one of the sessions, Sertac describes the collapse between his personal fate and that of Kurdistan: “. . . I can’t remember when the name of that homeland began to be memorialized as so-called, when all of these places became so-to-speaks, when they turned into probabilities, when they descended to the level of nothing, when they became nothing but sheer void . . . when, finally, that homeland became an unhappiness that crashed into me.” The fictional Sertac can’t even express his psychological anguish in his own language without the mediation of a translator (the translator, revealed at last), who asks him, “. . . don’t you trust my translation?” His words are then once again “translated” into the therapist’s official report, which describes the collapse between his real life and his stories. Yet this entire scenario, too, turns out to be an idle, fictional imagining of “the other Sertac,” who remains in his home, trying to finish a single story.

Diagnosing the plight of his people, Sertac explicates: “We Kurds live not in a postcolonial society, nor in a postmodern society, but in a posthabitable society . . . a society that has been torn apart and stitched back together.” Like Penelope, he weaves and unweaves his stories to the extent that he loses the thread entirely, a metaphor for the act of trying to narrate a history that is actively being undone. Yet even such loose threads find their frayed ends. In part four, “Signified,” a new narrator takes over in the first person: Alî Osman, one of Sertac’s students from the first part of the book. Through his telling, we learn about the shocking act of violence that brings Sertac’s tale(s) to a conclusion—one that reconfigures the positions of the teller and the told, the author and the character, the stories and the world they take place in.

In the book’s final act, a series of “Unfinished Endnotes,” Merasîm’s editorial voice returns, a development foreshadowed by Sertac’s description of her as “after all, in charge of everything.” Morphing into an increasingly frightening figure, she berates Sertac for his narrative choices. To this, he can only appeal, “I . . . didn’t . . . finish . . . the story . . . yet.” Young Sertac’s obsessive penchant for lying had made him happy, but Sertac the writer’s ceaseless storytelling tortures him. The title of the novel appears here for the first time, and we learn that Sertac is trying to apply to “The Competition of Unfinished Stories” under Merasîm’s watchful eye. In this inverted Scheherazade dynamic, Sertac is not inspired to tell stories to save himself and his people, but under frenzied duress.

Adriana Cavarero observes in Relating Narratives that “life cannot be lived like a story, because the story always comes afterwards, it results; it is unforeseeable and uncontrollable, just like life.” Ozmen’s novel illustrates this observation with great pathos, right up to the end. The notes shift from Merasîm’s feedback on Sertac’s manuscript to Sertac’s notes, concluding with his own unmediated account of his life that refuses to explain any of its inconsistencies or oddities: “Well, that’s just how things turned out.” With equal parts starkness and absurdity, incision and humor, The Competition of Unfinished Stories illustrates that when even the most banal facts of life—the letters of the alphabet, the diacritic over a name—become sites of battle, all the matter of reality must confront and interrogate its own fictionization.

Hilary Ilkay works in sales for the Canadian indie press Biblioasis, and she is an Associate Fellow in the Early Modern Studies Program at the University of King’s College in Nova Scotia. She is a Managing Editor for Simone de Beauvoir Studies Journal and an Assistant Managing Editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: