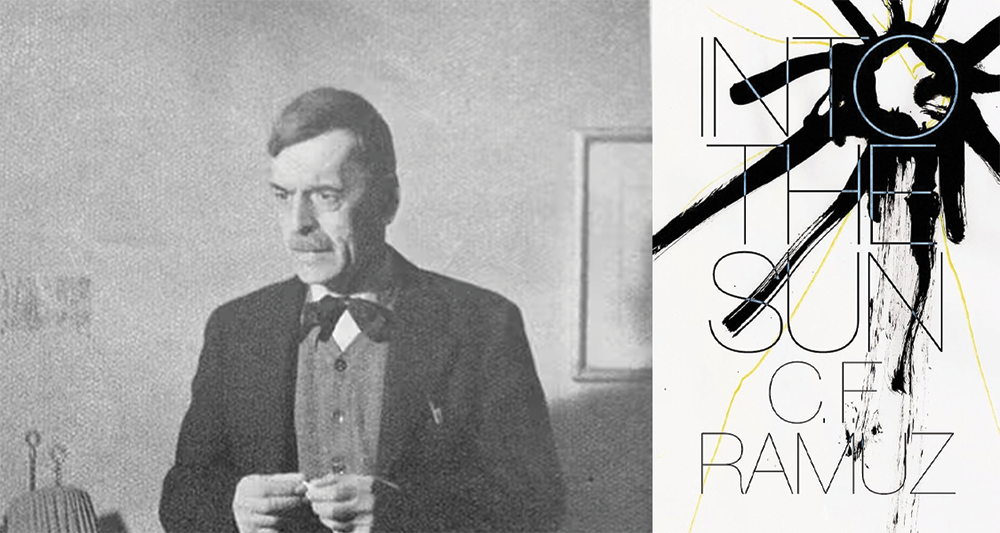

Into the Sun by C. F. Ramuz, translated from the French by Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan, New Directions, 2025

Originally published in 1922, C. F. Ramuz’s Into the Sun is a quietly devastating depiction of the climate crisis, centring its narrative around the predicted outcome of the sun eventually engulfing the Earth. Catastrophe narratives can lean into the dramatic, but among Into the Sun’s distinctive qualities is the resistance of hyperbolic description and genre conventions; instead, Ramuz’s novel is filled with clarifying depictions of manifold human reactions—particularly silence, denial, and the stubborn persistence of everyday life. The structure of the novel, too, defies expectation, being composed of a series of vignettes that do not necessarily follow a narrative thread. Rather, the discrete elements resemble individual short stories that share the same backdrop and quiet, elliptical narrative. The result of these stylistic combinations work to create a text that feels distinctly contemporary, given the current global concern for climate change and its repercussions.

Ramuz’s discreet, almost detached tone is evident from the novel’s early chapters: ‘Because of an accident within the gravitational system, the Earth is rapidly plunging into the sun.’ In presenting the facts with a clinical eye, the arrival of the central revelation is underplayed, only previously intimated via subtle mentions of rising temperatures. As the news then spreads globally, the small lakeside town in which the novel is set (unnamed, but clearly Swiss in its cultural references) carries on as if nothing has changed. The villagers hear the warning, but they do not believe it. According to the psychologist Matthew Adams, eco-anxiety can manifest in a variety of ways, including denial, and this tension between knowledge and enforced oblivion forms the emotional core of Into the Sun: Ramuz is less concerned with the mechanics of catastrophe than with the psychological and communal refusal to accept it.

In its scattered, piecemeal approach, the novel is minimalist and brief, without any overarching plot or clear protagonist. The vignettes, while providing a detached insight into the daily lives of disparate individuals, also help to illustrate the novel’s focus on community; most of the characters will never meet one another, but they share a single commitment to the construction of their shared world. Ramuz’s narrative is thus built through repetition, variation, and mood, overlapping across its various chapters. Themes evolve gradually, and despite this disparate approach, those willing to engage with the novel’s quiet intensity will be rewarded by its multiplicity. As the text proceeds, it touches on ideas of resource scarcity, indifference, negation, and more, allowing for an expansive social overview and a sense of simultaneity.

Furthermore, Into the Sun is compelling in its restraint. In eschewing scenes of panic or destruction, Ramuz focuses instead on atmosphere, tone, and the subtle shifts in collective consciousness. The villagers do not scream or flee—they simply wait, adhering to their routines for emotional self-preservation in the face of their upcoming predicament. As the final day approaches, one of the few named characters, the investor Gavillet, is given what is seemingly a tragic—though never explicated—end: ‘Gavillet opens the dresser drawer; he takes out his revolver.’ Although gunshots are then heard in other chapters, the target is left vague, and violence—both structural and interpersonal—is described only obliquely:

Just like that, they form something like republics; each village is one of these republics. Each village has gone back to the olden days when they were surrounded by walls and moats. Armed men are stationed on every path. They lie in ambush behind the walls, beneath the sheds, behind the large pear tree trunks;—and all that arrives: automobiles, bicycles, people in cars, people on horses, pedestrians—all is stopped.

Ramuz often blurs the line between narrator and character, between thought and observation, and the co-translation of Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan captures this fluidity with grace, weaving an emotional texture without losing the text’s strangeness. In its ambiguity, the prose gives nature a symbolic role to play; as the lake, the mountains, and the vineyards all remain untouched as the sun draws closer, Ramuz does not anthropomorphise the landscape, but rather uses it to construct metaphors for absence, emphasising the novel’s existential themes: that the world will endure, even if humanity does not. This calmness, then, becomes increasingly unsettling—a reminder of the universe’s indifference to human fate.

Where human emotions do come to the surface, the tone is one of quiet dread, evoking unease through stillness and inaction. The villagers’ passivity becomes its own form of violence, though Ramuz is careful to highlight that this refusal to act is not malicious, but deeply human. Denial is a coping mechanism, a way to preserve sanity in the face of the unimaginable, and such an empathetic approach takes the novel beyond a critique of industrial society, into a meditation on fragility. Ultimately, Into the Sun asks difficult questions: What does it mean to know something and yet remain still? How do we respond to threats that are abstract, invisible, or slow? What roles do community, belief, and tradition play in shaping our responses to existential danger?

In its measured boldness, Into the Sun offers a profound and unsettling experience. It does not shout—it whispers. It does not dramatise—it observes. It does not resolve—it lingers. In an age of noise and spectacle, Ramuz’s restraint feels radical. His vision of the end is not one of fire and fury, but of silence and stillness, and in that silence, we hear the distant echo of our own fears.

Darius Sobhani has worked as a translator for multiple British and Spanish literature-based NGOs.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: