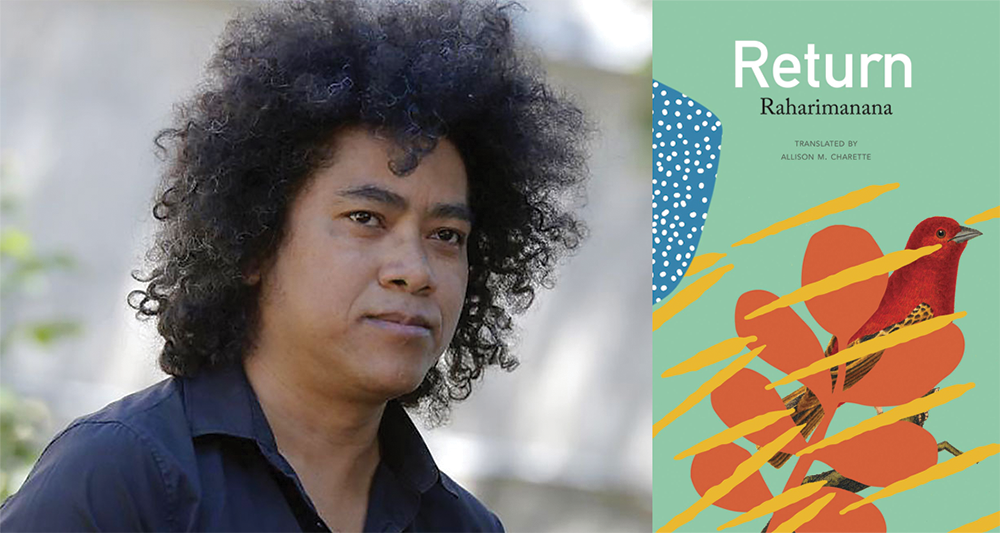

Return by Raharimanana, translated from the French by Allison M. Charette, Seagull Books, 2025

A newly independent nation. The visions of building. The sacrifices, people, losses. If this invigorating spirit is unwaveringly intoxicating, its effects are as much generational as they manifest in the present. In his novel Return, Raharimanana knits together a young man’s memories of his father and the spirituous strides taken to uphold truth against power in the aftermath of colonialism—specifically when the nascent country of Madagascar erupted in revolution in 1972 after gaining independence from the French in 1960. Hira, around whom much of the story revolves, is hailed as an oscillatory reminder of the time since Madagascar’s freedom, forming an autobiographical arc in Raharimanana’s own reconciliation with his childhood. The author’s writing also carries the artfulness of music, an art that he engages in alongside being a novelist, poet, and playwright.

In an earlier book, Nour 1947 (2001), Raharimanana penned a closer engagement with the 1947 Malagasy Uprising, dealing with the deadly killings of 87,000 Malagasys by the French colonial rule. Return, which was first published in 2018 in French as Revenir, now puts on a vivid image of Hira’s life as a touring writer and his recollections of the transitioning state of Madagascar. As he travels, he is disturbingly reminded of his father’s torture and the price paid by his family, and these fragmented recollections do not let him collate a neat history. Hence, the sections of the present are reeling with the irredeemability of time, a fracturedness that also speaks to the inability to write of a violence that is both collective and overpowering. As the novel moves on, this position culminates into renewed impetus for his writing, rife with image and poetic terseness. Being born after independence, Hira is part of a nation attempting to blossom a life out of the ruins—and this is true for Hira’s own family as well as for the country. For him, it is tiring: “But also weariness. He’d had enough of all of that. Being confronted with his country’s violence.”

But as a new nation, a wave of optimism runs through. Little victories are celebrated. The signs of the French are removed and new ones are installed in its place. New faces come in. And yet the descent into nationalist devotion is quick, subtle and in plain sight; the symbols of the nation begin to be defined along lines of divide. Half the novel is told through Hira in his childhood, also a period of transitioning into autonomy, as he documents the changes happening all round him in a weighty yet humorous voice.

Hira is witness to “Malagasization,” and he reflects on the cause of it: “The term ‘Malagasization’ was the most surprising, the child Hira never had a doubt about being Malagasy, why would he have to get more Malagasized? It was perplexing, he didn’t understand why these adults—they were very clearly not Vazaha, not French—why did they have to be made Malagasy again, when they already were?” “Malagasization” is not of the “Vazaha” (a local term for foreigners) or the “French,” but of the Malagasys themselves, a new and repeated act of formation of the self against the French colonialists. However, as is the fate with other decolonized nations in history, this direction ends up taking one community as the sole bearer of the national identity, and merely replaces a tyrannical foreign entity with a punitive native regime. The faces change and nothing more. It also prompts one to look at times of decolonization as a long-drawn and often confounding process: What would the symbols of the new nation be? Its language, its idioms, its tribes? And more, importantly, who isn’t Malagasy?

The narrating child also betrays a playful but curious eye. Having been born during the dictatorship, he acknowledges that his life was better than his father’s, who had given his soul to this liberation. They were now free of “neocolonialism,” beholding a revolution that “they heard on the radio, repeated over and over again.”

The torture of Hira’s father is a significant moment in the novel; it is the fracturing of Hira, a moment which comes back to him again and again as he reflects on his own relationship with his wife. His father had seen the advent of the revolution, only to be abducted and abused by the new government years later. This is also tellingly remarked by one of the martyrs of the revolution that Hira sees in his dream: “I do not know why all the ones we bring to power become a dictator!” Witnessing his father’s pains, Hira finds himself wavering over the ideal for which his father lived his life. Later, as he is writing, he wishes to avoid stories of his father’s childhood because he confesses that it is not for him; his father can write that himself.

It is also here that Raharimanana hints at the central question of his novel. He writes, “He would not know that the Return was toward not a place but a love.” For Hira, this unfulfilled return was always to his wife. Although her figure is left bereft of a voice (which is more puzzling than it is unusual), she is persistently there in the shadows, holding on to Hira whenever he needs her. It is her that he moves towards, rather than towards a physical presence of a place, because he knows he will fail miserably at the latter.

On a colonized land, this question of place expresses the displacement that we see in Hira and the generations that came in the wake. At the novel’s inception, Hira is taken away by the sea while on the rocks, and in the waters, he awaits the moment of his death, his drowning gasp under the sea. In Derek Walcott’s poem “The Sea is History,” he describes the History that is still unwritten, locked in the sea’s “grey vaults,” and it is only in drowning where one’s History can really begin. Hira shares this sentiment, and eventually, he allows the sea to take him away, to let him feel that History for once, a chronicle that he is yet to encounter in the annals that he or his countrymen know.

The translation by Allison M. Charette is distinctive and remarkable; the poetic voice of Raharimanana is so connected with his fiction, and thus, the translation is expected to be as resonant in verse as it is in phrase. The fourteen “notebooks” of Return are suffused with the musical quality of the writing, as well as filled with dream-like sequences, and Charette’s translation does not seem outside of the text. Rather, it is involved, infused, and as entangled as Raharimanana’s own voice is with Malagasy people and language. She has kept intact the various, frequently shifting registers that evince the novel as emerging from a writer and a place that has a troubled history with language. Even as the author himself discloses that the reason he wrote in French was that “the [Malagasy] language had turned so rotten,” the translator has accounted herself to all that the novel concerns. Hira recounts that he “liked it when his mother spoke Antakarana to him. He always thought his mother was singing. He’d answer in Merina. He would shift between different vernaculars. . .” Malagasy or Antakarana or Merina are not negations in the English translation; together, they form the very contours of the translated text.

Return is a boiling encounter. It breathes in all ways. In fire and smoke. Drowning one in its histories. Raharimanana takes you to the sea and back, across all its waves, rocks, birds, stones, and sands. It is a chronicle of a land that mourns but of a people that live on. It is a silhouette set against the twilight end of the day—a long day coming to a close, a slightly reddish sky that remembers what happened years ago.

Shaiq Ali is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities USA.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: