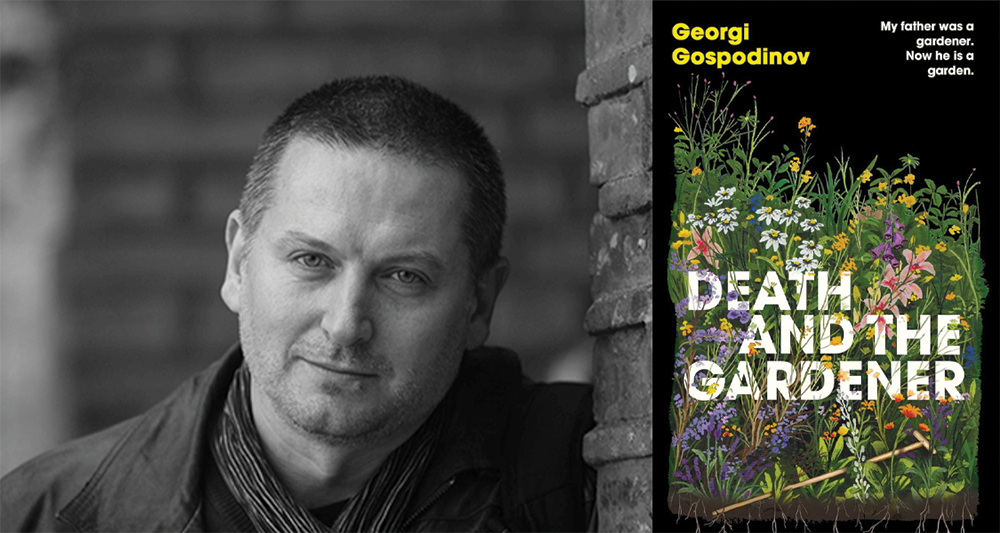

Death and the Gardener by Georgi Gospodinov, translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel, Liveright, 2025

“What happens to the garden . . . when the gardener is gone?” asks the narrator of Georgi Gospodinov’s new novel, Death and the Gardner. After winning the International Booker Prize in 2023 for Time Shelter, the Bulgarian writer returns with a novel featuring a similarly famous Bulgarian writer—with the additional autobiographical detail of a father who has died from cancer, leaving his garden behind. Within this autofiction, the reader will not have to wait long for an answer to that primary, haunting question: “The garden will continue to flourish, even without its gardener, what he has planted will still grow, bear fruit, but wildness will also start to make inroads, after some time weeds and grasses will overtake everything.” The seasons will cycle the plants through life and death—and life again. In a garden, even without its gardener, there is still promise of spring; perhaps it’s this promise of revival that makes gardening an ideal outlet for grief.

I began my first garden three years ago as my dad lay dying of cancer in the living room. His friends—now my friends—had shown me how to hoe a straight line between two markers and brush in the seeds, then how to cover them with soil, going back down the lines. What they couldn’t do was prepare me for when the tilled dirt filled with weeds, for when my dad died and I inherited his house and its garden. That first summer, I ripped up endless roots, but the weeds kept on growing.

The narrator of Death and the Gardener does not work at his father’s garden after he dies, but he does use it as the central grounding image for the book that he writes. Though Death and the Gardener calls itself a novel on the cover, it reads with the intimacy of a memoir in Angela Rodel’s expert translation. Acknowledging this slippery approach to genre, the narrator admits, “This book has no obvious genre; it needs to create one for itself.” He too wonders “whether the kindling of those words cools [grief], or just inflame it all the more.” Writing, then, is taken to be like gardening after a death: a way to bargain for just a little more time with that person. This cathartic use of writing (and gardening) in grief is nothing new, but Gospodinov’s approach draws particular attention to the push and pull of the writing itself, and how this kind of detailed remembering both brings back his father and reproduces the trauma of witnessing him suffer and die.

Death and the Gardener starts when the cancer and pain return to the father’s body. Dinyo is seventy-nine years old and had throat cancer seventeen years ago. Now it has metastasized everywhere. Returning to the narrator’s home in Sofia, Dinyo doesn’t ever again leave on foot, and the subsequent narrative of his death proceeds by short, fragmentary chapters that move back and forth through time. As the famous writer-narrator takes short trips to European cities, he recalls his father’s previous illnesses or how his father tirelessly worked in his garden. At first, the narrator avoids recounting the death itself, “elongating his [father’s] final days . . . thinking of stories in which he is alive.” In the writing, death can be set aside, at least for a time.

When the emotional pitch of the writing resonates too near the soft tissue of grief, the narrator invokes his father’s “first-rate stories.” Initially, these are inserted into the text to fill in Dinyo’s character, portraying him as someone who has a story for any situation, embellishing moments of failure and embarrassment with humor. As such, these stories become “first-aid stories” that the narrator employs as a salve. There is a story about how Dinyo had hung the family’s laundry at night to avoid the men in his village catching him doing women’s work. There’s one about how after Dinyo’s first cancer operation, a rumor went around town that his head had been cut off. When a neighbor called to confirm, Dinyo replied, “Hang on a second while I get my head and I’ll tell you about it.” They are stories that inflate or make a joke out of tense or difficult situations, stories that don’t take themselves too seriously—a way of facing and not facing at the same time, just like Dinyo’s motto, “Nothing to fear.”

In this sense, the fiction of Death and the Gardener is a distancing technique that both father and son employ, suggesting that the only way to get through both death—and life—is by transforming experiences. Early in the novel, when father and son are sitting in the doctor’s office, Dinyo lists out and exaggerates every injury and illness of his nearly eight decades. The narrator observes: “Only when he was telling stories did his ribs not pinch him, his lower back not saw him in half, his lungs not stab him; there was no trace of the pain.” Fiction, in this case, becomes a miracle cure, a way of moving beyond the physical; we become the stories we tell more than the person telling them. Of course, such fictions are preferable, but not even the most skilled storyteller can hold off the pain and fatality of cancer.

After Dinyo dies, the narrator fills in his father’s biography. He was born at the end of World War II in a Bulgaria quickly overtaken by the Soviet Union, and the narrator emphasizes both instances of his father’s individuality—how he refused to attend the required September 9 communist festival, or continued to wear tight pants—as well as Dinyo’s similarities to other fathers of that generation—whose name would be invoked when punishment was needed. “It is harder to write about fathers,” the narrator writes. They are “shadowy, mysterious, sometimes frightening, often absent—clinging to the snorkel of a cigarette, he swims in other waters and clouds.” The mother is central while the father is lingering on the periphery of a child’s life, difficult to bring into focus.

In Bulgarian culture, fathers are shamed for expressing their emotions. Perhaps because of this repression, Dinyo found his method of expression in his garden. The narrator realizes: “In a culture where it is not customary to say things like I love you, I feel so bad for you, I miss you, and so on, people find different ways to express their love.” In Dinyo’s old age, he had constantly worked on growing enough flowers and vegetables for the whole family, and the narrator attributes this plentifulness as a declaration of his father’s love—all those peppers and eggplants. This aspect of gardening as a form of wordless communication might seem like an inverse to the craft of writing, but both allow their practitioners to pile on meaning and to try and grasp at emotions—like grief—that make little sense.

Gospodinov prolongs the end of Death and the Gardener as much as he prolongs retelling the moment of Dinyo’s death. Short chapters trail off and are followed by an epilogue, but eventually, the narrator has no choice but to end the book, which has been a kind of memorial to the fathers who die on our watch. In the last chapter, he writes: “I don’t know what to do with this thing I’m writing, which is supposedly for him, but it’s also for me and for all the fathers whose footsteps we race to catch up to.” What is more universal than losing a parent? Through the power and magic of fiction, Gospodinov transforms his individual mourning into a sensitive and moving work of art that is both devastating and comforting.

In the garden these days, I’ve learned that weeds can be managed but not controlled, that autumn is not as sad as I had thought. Once the frost shrivels and browns the outsized zucchini plants, I clear weeds for the last time. There is so much vegetal mass that comes out of the garden, wheelbarrows full of brittle stems and limbs that I dump in my brother’s harvested fields like strange animal mounds. And through the frost, some plants grow on. The kale and brussels sprouts, the carrots and potatoes. Then a long stretch of hard cold kills even the hardiest. At this, I’m relieved, because then I only eat instead of laboring, making my way through the stored potatoes, onions and garlic, the canned tomatoes and pickled green beans. My dad never taught me to garden in his lifetime—I was always away. But he teaches me now. I understand Gospodinov’s difficulty with ending his novel. He’s gone. He’s with me. He’s gone.

Amber Ruth Paulen is a writer and educator living in rural Michigan. She earned her MFA in fiction at Columbia University and is currently writing a multi-generational novel about the struggles to keep one family farm running and the costs of an inheritance.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Grief and Knowledge in a Dying World: A Review of Inn of the Survivors by Maico Morellini

- Deep Time Elegy: A Review of What good does it do for a person to wake up one morning this side of the new millennium by Kim Simonsen

- Memory as Political: On Raja Shehadeh’s We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir