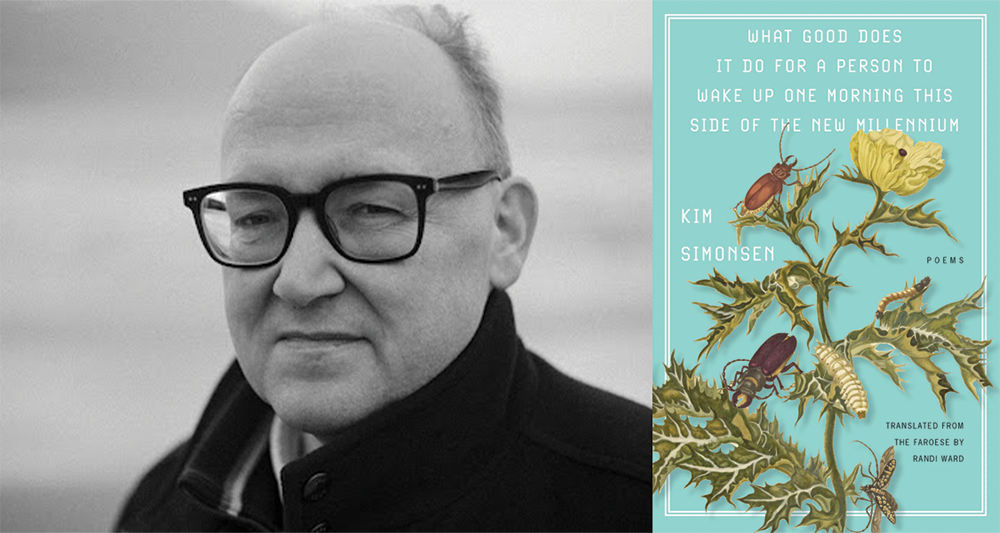

What good does it do for a person to wake up one morning this side of the new millennium by Kim Simonsen, translated from the Faroese by Randi Ward, Deep Vellum, 2025

In seeking an entry into Faroese poetry, one should begin with Kim Simonsen, an award-winning writer and academic from the island of Eysturoy. Having been active for over two decades in conventional academia as well as in artistic circles, he is also the founder and managing editor of a Faroese press called Forlagið Eksil, and is the author of seven books as well as numerous academic papers. Hvat hjálpir einum menniskja at vakna ein morgun hesumegin hetta áratúsundið (What good does it do for a person to wake up one morning this side of the new millennium) won the M.A. Jacobsen Literature Award in 2014, and now, its translation by Randi Ward into English will be published by Deep Vellum in 2025. Written in free verse, the collection aspires to juxtapose the vast sweep of geology with the relative miniature of humanity, invoking the life cycles of organisms and landscapes whose timescales dwarf our own lives. Yet, the lyric centre of these poems is grief; the speaker has lost their loved one, and here measures their absence against the timelessness of eons. Divided into four parts, the book is also interspersed with illustrations from natural history texts such as Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705), Leopoldo Caldani and Floriano Caldani’s Icones Anatomicae (1801-1813), and Frederik Ruysch’s Thesaurus anatomicus primus (1701), among others.

The titular line comes in the first couple pages: ‘What good does it do for a person to wake up one morning / this side of the new millennium. / The body turns to ash (the ash weighs nine pounds). / No closure, no explanation to be found.’ This measured calmness, preciseness, and gravity endures through all the other poems, letting the details do their own emotional work. This is particularly effective in a moment wherein Simonsen catalogues the human body in clinical increments:

. . . the electrical currents of the brain are

like a ten-watt lightbulb’s.

A decapitated head weighs nine pounds.

. . .

The face uses 43 muscles to wince.

Effacing the dryness of an anatomical list with emotional power, the poet returns to this device throughout the collection to compress intimate loss into readable units, allowing grief to be experienced without being romanticized. In this manner, Simonsen entrenches the electrical and the neurochemical within the experiential nature of human consciousness.

So it is that much of the book’s energy comes from its juxtaposition of scales. Simonsen moves from domestic ritual—’We still pour coffee from the same black / pot . . . / Still eat bran flakes and muesli’—to geological and cosmological time: corals and plants that have been around for millennia, and the sun’s future expansion into a red giant that finally consumes the earth. The collision might be jarring at first, but soon one comes to appreciate the difference between localised tenderness and cosmic insouciance. ‘Nature is indifferent. / It’s just us, this morning.’ It’s both an observation and a kind of test for the reader; if we accept this indifference, what meaning lies in a mundane morning? Where does love and belonging fit in this timelessness?

The diversity of biological life cycles is beautifully incorporated in the first part of the book. It was a treat to visualise the mitotic cell division (the function of the mitotic spindle is to assist in equally dividing the chromosomes in the parent cell, which are passed on to the daughter cells) against the passage of millenniums (‘while the third millennium draws spindles / between cells that have yet to be born / and the will to live’).

In the second part, we move from cosmic imageries to terrestrial and subterranean ones, depicting the death of organisms and the grief percolating through changing seasons. Simonsen describes a scene of ‘four brown killer slugs silently devour / two smaller black slugs’, calling it: ‘A landscape of silent annihilation.’ That same silence permeates the house at the end of the summer when the narrator comes down with a viral infection, and autumn appears to be on the horizon.

At this point, his longing for the absent beloved now moves into more tactile and viscous language. Recurring images of oil, mucus, and seawater are not merely sensory, but conceptual. ‘There are millions of virions / in a millilitre of seawater. / If we lined all of the virus particles up / end to end, they’d stretch / 200 million light years.’ In Latin, the word virus means ‘slimy liquid’ or ‘poison’, and the poet notes that his beloved’s eyes glisten due to fish oil. Such hyperbolic metrics and comparisons insist that any scale can be surmountable: the same viscous matter is at the base of viruses, brains, and oceans—so both intimacy and apocalypse share similar ingredients.

One of my favourite poems contains a list of geological periods, from Precambrian to Jurassic, which reads like the ghost of a childhood lesson. Now, time’s passing is stricken with the planet’s numerous systemic problems, climate change being one of them, and similarly, the speaker’s affection for classification—plant, animal, and mineral kingdom—is softly challenged against the depth of grief when he asks, ‘Who can help me / find a place / in this world / now that you are / no longer here?’ Still, a tender philosophical acceptance comes midway through the book via Hegel’s idea that true infinity cannot be comprehended. The narrator first names the beloved as the universe, then embraces mortality as a necessary aspect.

I should mention that these fascinating imageries are a testament to Faroese, one of five languages descended from Old West Norse spoken in the Middle Ages, and currently spoken by approximately sixty-nine thousand Faroe Islanders (as mentioned in a 2015 report). It is a tongue marked by its survival against time’s attrition. Even in English translation, one hears the tug of a language shaped by wind, ocean, winter, and remoteness. This linguistic texture gestures toward something the imagery alone cannot hold, the endurance of small, fragile forms in the face of vast erasures.

The book sits well alongside other writers who attend to scale and matter. First and foremost, I am reminded of Timefulness by Marcia Bjornerud. Speaking of geology’s usefulness in understanding our future on earth, Bjornerud writes:

Our natural aversion to death is amplified in a culture that casts Time as an enemy and does everything it can to deny its passage. As Woody Allen said: “Americans believe death is optional.” This type of time denial, rooted in a very human combination of vanity and existential dread, is perhaps the most common and forgivable form of what might be called chronophobia.

She goes on to says that humans have no appetite for stories without human protagonists. ‘We are both intemperate and intemporate—time illiterate.’ Within the constant flow of information, contemporary existence is hyperaware and drip-fed, which makes everyday life a plateau of boredom, comparable to the slow tectonic movements of the planet. Simonsen’s poems, then, adjusts our parameters just enough to give the cosmic vastness the attention it deserves.

If the book has a modest shortcoming, it is the occasional tonal lurch: an abrupt swing from a black iPhone alarm into astronomical galaxies can feel unexpected. The grief is palpable, but the leap from personal loss to epochal vision feels tenuous at certain moments, and I found myself wishing for a bit firmer ground. But perhaps mourning does not follow a linear and gentle rhythm, instead moving within the associations that Simonsen lists for us: anatomy, taxonomy, breakfast, coral, beetles, mosquito bites, star-death. These interruptions are honest reflections of the disjointed nature of grief, rather than the careful curation of a beautiful lyric. As such, this is a book for readers who prefer elegy that is alert rather than ornamental. If you want compact lines that catalogue the humbling facts of human bodies, galaxies and starts, the electrical potential of neurons, aquatic life, insects, slugs—then Simonsen is a precise and unshowy companion. If one is to complement this book with nonfiction titles such as Bjornerud’s work, Robert Macfarlane’s Underland, or Notes From a Deep Time by Helen Gordon, the ground would be laid for a more grounded and robust understanding of how necessary deep time education is in today’s world. The verdict is that not everything ends, but it is cyclical in nature—whether it be organic life, the sediments of earth’s crust, or mourning your loved ones.

Sayani Sarkar has a PhD in biochemistry and structural biology from the University of Calcutta. She writes academic book reviews and interdisciplinary essays on her Substack newsletter called The Omnivore Scientist. Her reviews and essays fall within an intersection of science, nature, languages, arts, culture, and philosophy. Her works have been published in Full Stop, Tamarind Literary Magazine, LARB PubLab Magazine, Littera Magazine, The Coil Magazine, and The Curious Reader. Currently, she is the Editor-at-Large (India) with Asymptote Journal and a creative nonfiction reader for Hippocampus Magazine. She lives in Kolkata, India.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: