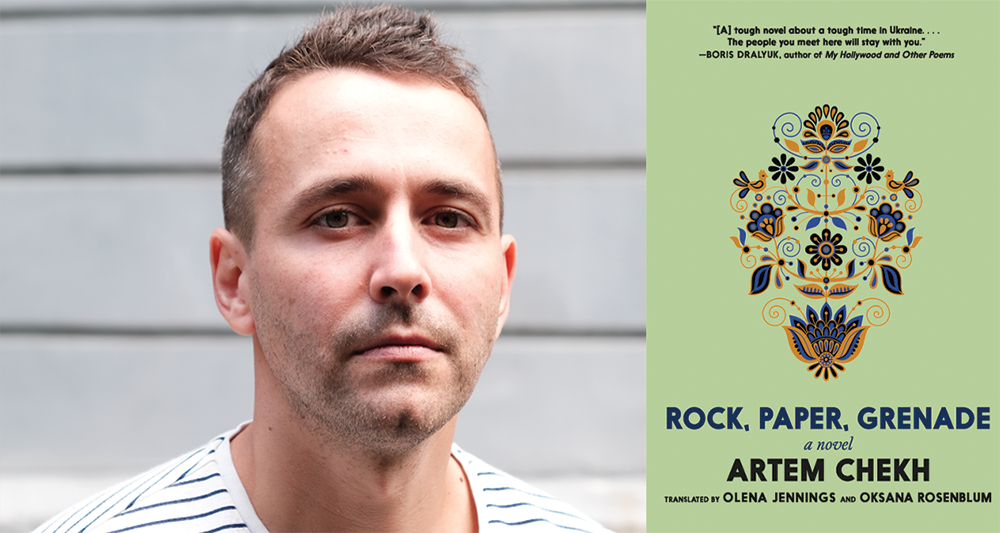

Rock, Paper, Grenade by Artem Chekh, translated from the Ukrainian by Olena Jennings and Oksana Rosenblum, Seven Stories Press, 2025

When men talk about other men in the world of Artem Chekh’s Rock, Paper, Grenade, there is an external sense of kinship coupled with a subtle hostility—a language of insults and mockery that permeates every interaction. And within this, nothing is more feared and ever-present than the specter of queerness. Felix, the stepfather of protagonist Tymofiy and a prominent character throughout the novel, had experienced a “fulfilling and, by and large, carefree childhood,” yet still casually criticizes his brother for a perceived femininity. From comments about his choir involvement and “sailor suit” to the accusation of being a “faggot and wimp,” his familiar descriptions of his brother are laced with casual homophobia.

Throughout the novel, the F-slur is routinely thrown about when a male character behaves with vulnerability, and any feminine quality in men is roundly scorned; as such, Rock, Paper, Grenade is, at its core, a novel about how masculine social dynamics can transform and change its characters’ emotional lives. Felix’s presence is emotionally fraught for Tymofiy; when the two meet, Felix provides a role of care, yet he also uses hegemonic, power-driven masculinity—and its undercurrent of homophobia—to cause profound harm. In Chekh’s world, this duality of male vulnerability and aggression is of utmost importance, creating dramatic tension between the characters while underscoring the broader point that patriarchal behaviour profoundly traumatizes the emotional lives of men and boys.

Rock, Paper, Grenade—originally written in 2021 by Chkeh, a Ukrainian writer and journalist—was recently translated into English by Olena Jennings and Oksana Rosenblum, making it accessible to an English-speaking audience at a time when the need for solidarity with Ukraine has never been more intense. Despite the shadow of post-Soviet conflict in the background, the novel represents a slice of life rather than a dramatic wartime narrative. When it begins, Tymofiy is five years old, and as we witness his growing-up into a young adult, so also do we understand his intense relationship with Felix, whose alcoholism, aggression, and post-traumatic stress intensely complicate their dynamic. Thus, Rock, Paper, Grenade bridges the gap between historical fiction—exposing the atrocities and trauma of sweeping events—and a coming-of-age novel that explores the dynamics of a shifting and evolving family. Tymofiy’s gender socialization and self-actualization regarding masculinity also play a central role; interacting with Felix shows him a gruff, intimidating form of manhood, yet their dynamic also shows him what care between masculine-identifying people can look like, shaping his views of gender.

From the very first page, Felix is shown in a deeply contradictory light, both heroically protective and emotionally closed off.

Felix rescued Lida. He often accompanied her when she was swimming. He walked into the distance, smoked, walked carefully along the icy quiet surface of the reservoir, looking toward the fairway, as if expecting desert caravans of dushman armed with Stingers to swim out of the frosty haze. But, of course, there were no caravans. And, of course, no dushman either. And when he looked back, there was no Lida. Felix rushed to the ice hole and beneath the murky ice he saw her gray flailing body. He threw off his jacket, plunged to the waist, slid his fingers along her body, looked for something to grab onto, finally grabbed her hair, pulled.

Immediately one glimpses the contradictions of traditional masculinity. The scene focuses on Felix’s physical might rather than his emotional sensitivity, yet he also exemplifies a chivalrous, protective role. From thereon, Chekh reveals the most painful aspects of Felix’s emotional life, showing him as a war veteran with shell-shock (CPTSD in today’s terms), an inability to find community, and a pattern of being aggressive and suspicious toward his partners. Eventually, he meets Lida’s daughter, Olha, who immediately idolizes him for his courage in the face of fascism and repression. One thing leads to another; he grows closer to Lida’s family and begins to stay with them regularly—a development that Tymofiy, Olha’s son, welcomes at first: “For Tymofiy it was the happiest year and a half, without worry and with a drunken lightness, as one often remembers the time before a war or an epidemic.” With Felix in the house, Tymofiy feels cared for, protected, and simultaneously reassured of the unthreatening and safekeeping quality of masculinity.

But Chekh takes care to emphasize Tymofiy’s vulnerability, with the third-person omniscient narrator stating that: “When you are five, you can hide the whole world in a matchbox. Everyone around you loves you, and you carry this love like a beetle caught on the burdocks.” Yet this feeling of smallness and belonging quickly breaks down—along with Felix’s veneer of magnanimity. As he grows increasingly unpleasant, he still tries to endear himself to Tymofiy, but the five-year-old easily sees through his “seemingly loving look, as adults usually look at someone else’s kid whose affections they want to gain.” Then, as the young boy starts first grade, he begins to resent Felix for monopolizing his mother’s and grandmother’s attention, causing interpersonal conflicts between the family members, regularly drinking to excess, and quietly rupturing the emotional health of Lida’s household.

Meanwhile, Felix’s regrets about his past continue to haunt him, and his vivid, traumatic flashbacks frighten Tymofiy—especially as the older man, while intoxicated, is inclined to believe that Tymofiy is an “old battle comrade” rather than his young stepson. Yet even as masculinity and fatherhood begin taking on a threatening undertone, Felix is still much more open with him than Leda or Olha are; their interactions constitute the “first time an adult told Tymofiy about sex, about death, about rage and honor.” Through these incidents, we see the emotional neglect that accompanies a bipolar affection dynamic, wherein kinship can be petrified by aggression. As a result, a feeling of belonging never fully develops in the young boy: “Sometimes Felix asked him to call him Grandfather, but Tymofiy could not get himself to do it. There was something artificial and plastic in it, an outright fiction, an attempt to mask cracks and troubles.” And despite Felix’s longing to be seen as a caregiver, he consistently undermines himself; when he comes home drunk and physically ill, it falls to Tymofiy—rather than his mother or grandmother—to handle it.

Through this period of early childhood, Felix leaves and rejoins the family with a vengeance, instilling a deeply insecure sense of attachment in his stepson, but also inspiring him to adopt a softer, less threatening masculinity. By his third year in school, he is studying theater and music, using the arts as an escape from domestic aggression (notably, both art forms are historically queer, signifying a departure from Felix’s fear and hysteria around gay male existence). Tymofiy’s friends, mainly boys his age, are sensitive and artistic rather than violent, distinct from Felix’s male friends, whose homosocial kinship is almost exclusively based around aggression. Thus straddling the barrier between two different forms of masculine identity, Tymofiy feels the pressure to assimilate; at one point, as a ten-year-old, he uses fascist imagery that he has seen in public while being mostly unaware of its meaning, and Felix does not intervene.

Yet despite attempts to blend in, he is still teased and belittled by his peers for his perceived femininity, and here Chekh portraits the profound impossibility of gender conformity. When he attempts a romantic relationship, he begins to parrot Felix’s worst traits, alienating his partner to the point that she leaves him. After subtly realizing this, he reaches a crisis, trying “to hang himself in the bathroom with his mother’s tights, which he fished out of a basket of dirty laundry.” This act of desperation symbolizes his eventual perception of gender as an impossible double-bind caused by his upbringing; femininity, symbolized in the tights, is his weapon of choice, but it is the imposed convention of masculinity that reduces his will to live.

In the very last vignette of the novel, Tymofiy (now a young adult) is forced to physically confront Felix, despite knowing that his stepfather is much physically stronger than he is. Yet the older man, deeply afraid of remorse and shame, entirely ignores Tymofiy after the encounter:

Two years later, taking a stroll through his native city, Tymofiy ran into Felix by the intersection near the market. Felix stood there, swaying; he wore a military field jacket, a black cap, and pathetically worn-out sneakers with no laces. Tymofiy ran up to him and called out, “Petrovych!” Felix looked at him indifferently, shaking Tymofiy’s hand in silence.

Rock, Paper, Grenade is not a novel that attempts to be idealistic or cynical about father-son relationships. Instead of depicting Felix as entirely villainous, Chekh opts to sketch him as a tragic figure, simultaneously threatening and utterly removed. In this, homophobia and even traditional masculinity are seen as forces of intense social isolation, turning familial relationships into battlegrounds. At a time when anti-queerness in the US has reached frightening extremes, and as war exacerbates some of the cruelest and most brutal aspects of gendered existence, a translation of this novel has never been more crucial, reminding its readers of the way that hegemonic gender can reduce everything to a fear-based performance.

mk zariel {it/its} is a transmasculine poet, theater artist, movement journalist, & insurrectionary anarchist. it is fueled by folk-punk, Emma Goldman, and existential dread. it can be found online at https://linktr.ee/mkzariel, creating conflictually queer-anarchic spaces, and being mildly feral in the great lakes region.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: