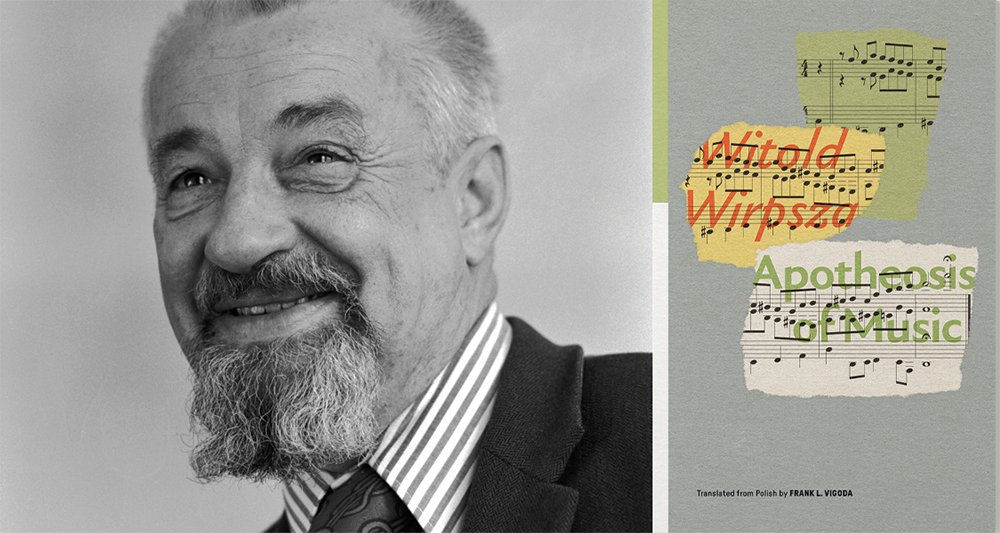

Apotheosis of Music by Witold Wirpsza, translated from the Polish by Frank L. Vigoda, World Poetry, 2025

In the fourteenth century, writing from a state of political exile from Florence, Dante gave us an allegorical tour of the afterlife with an imaginary Virgil as his guide, presenting a cast of historical and mythic figures re-imagined. It isn’t hard to make the connection between him and the twentieth-century Polish poet Witold Wirpsza, who, as he contended with World War II and its subsequent outfalls, wrote from a state of exile in West Berlin and introduced his own cast of mythic figures: Dante, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Stalin. Now, from Frank L. Vigoda—the nom de plume of translator husband-wife duo Gwido Zlatkes and Ann Frenkel—comes Apotheosis of Music, a selection of Wirpsza’s cerebral and exuberant oeuvre in an indulgent, cheeky, rhythmic English, at times originating its own pleasant musicality. Where Zlatkes lends his native Polish perspective, Frenkel’s background in musicology allows for an execution of the musical structures and themes prevalent throughout Wirpsza’s work.

Born in Gdańsk, Poland in 1918 and educated in music and law, Wirpsza was drafted into WWII, held as a prisoner of war in a German camp, and, after initially being a supporter of communism following the war, eventually defected from the Polish United Workers Party (PZPR) in objection to its policies. After publishing an essay critiquing nationalist identities called “Polaku, kim jesteś” (Pole, who are you), he was banned from publication in his native Poland—a sentence that lasted until 1989, four years after his death. He then settled in West Berlin, where he lived for the remainder of his life; there, he brought works of Polish literature to a German audience and vice versa, translating works like a biography of Bach and a novel about Mozart from German into Polish.

During the poet’s lifetime, the publication and distribution of his work occurred primarily through underground networks, although much of it was exhumed and brought to light after the publishing ban was lifted. To the modern reader who may be grappling with a time of rising authoritarian currents, human rights violations, and archaic land grabs, Wirpsza’s work may provide some guidance as to what the artist’s role could be in the face of humanity’s darker moments: namely, to bear witness to the world in a totality of both beauty and horror, to cling onto the soul, and to pursue artistic ecstasy above fame and recognition, insisting that one’s work belongs entirely to oneself.

Many of Wirpsza’s texts incorporate music: theories on composition, examinations of instrumentation and performance, and details on the mythos of musical-poetic figures. In “Apotheosis of the Dance,” from which this bilingual collection draws its name, such figures are anachronistically given fantastical biographies, culminating in fugue states of psychic dissolution. Beethoven, over a century old, is dragged away by dwarves of madness; Stalin, placed as an English sentimental poet, slays the innocent in a fever seemingly induced by Hekate; Dante flunks out of torture school and dances himself into exile. They act here as cautionary fables regarding the role of the poet and the interaction between art and its audience, but in form and arrangement, “Apotheosis of the Dance” also serves as a prime example of Wirpsza’s signature adaptation of musical forms into verse; the poem mirrors a sonata, consisting of exposition, development, and recapitulation. He introduces a theme, develops a series of variations on the theme, and combines elements of the theme and its variations into an ecstatic culmination.

Wirpsza also showcases this idiosyncratic style in poems like “Bridges,” in which he centralizes the structure of a theme that had previously only been introduced to bridge two main themes:

If by chance they appear as principal

Themes in another piece, they surpass

In excellence anything expressed earlier

In the themes they bridged.

But such thematic explorations are not limited to single poems. In one of the development verses of “Apotheosis of Music,” young Stalin is both a sentimental poet and a slave in the Middle Ages who learns to forge weapons of Damascus steel. Later, he sees his poetry alchemizing into such a weapon, with which he unknowingly slaughters some maidens that he perceives to be wolves. Immediately following this poem, then, is a piece entitled “Damascus Steel,” wherein Wirpsza develops this titular theme further by presenting a legend of Damascus swords, which are traditionally hardened by being plunged into the abdomens of slaves; this, Wirpsza’s narrator contends in the poem, is a more noble act than the self-perpetuating machine of war and power, for at least the slave dies to give birth to a weapon born of craftmanship, as opposed to the many deaths due to senseless atrocities, committed in the name of power and resource agglomeration.

Throughout the collection, the poet borrows from the music world’s biographies as well as its techniques. “A Little Theory,” which interweaves two melodies in counterpoint form, tells of Mozart, Bach, and the evolution of musical instrumentation. Wirpsza here reveals himself to be more sympathetic to Mozart than Bach, who is framed in the poem as balanced and sanitized, hiding behind the organ—which plays its sound at the same strength regardless of how much timidity the player brings to the bench. In contrast, by the time the Mozart rolls around, the pianoforte had been invented, and new dynamics were laying emotions bare, allowing for a more comprehensive representation of emotion beyond Bach’s utopian transcendence. Mozart’s pieces present a particular challenge to its musicians, who must rely on themselves rather than the instrument for resonance, thus required to exhibit greater agency.

Musical compositions change depending on their presentations, which is a particularly apt analogy to Wirpsza’s position as both a writer-in-exile and a translator. In “The Smuggler,” he uses the difference in instrumentation as a metaphor for literary translation, portraying the transposition from violin to piano as a border crossing, and drawing in the concept of shifting borders in the twentieth century. Describing someone carrying “the sack of notes / from point A to point B,” he mimics the instructions on the sheet music to “use the pedal sparingly” so that the piano might, in vain, mimic the violin. Just as one might wonder at what of the Polish may be lost when Wirpsza’s work is brought into the English language, we can imagine Wirpsza grappling with his estrangement from Polish audiences in attempting to present Polish literature and concerns to the intellectuals of West Berlin.

From a contemporary standpoint, Apotheosis of Music also brings to mind comparisons between the censorship of its author under left-wing nationalism and the current predicament of political repression under rising oligarchies and right-wing authoritarianism. To Wirpsza, the most important responsibility of the poet is to represent the world as it is—never using language on behalf of outside entities nor tempering perspectives out of fear, but bearing witness to the world and conveying it as holistically as possible. The poet must not shy away from despair or make any allegiances, certainly not to sanity. “Poets, hear me, my character / Will be flawless, i.e. this new me will never be disloyal, but I / Am not yet—poets, listen—I am not yet, in truth I am / Scared and trembling, just random atoms flitting about.”

Estrangement from artistic craft is a matter of great concern to Wirpsza, particularly as it pertains to the implications of industrialization, war, and the industrialization of war brought about during his lifetime. In the poem “Christ Distributing Milk,” he compares a laborious wood carving of a fish on a crucifix to breast milk, juxtaposing it with cheap industrial production and self-perpetuating cycles of conflict, which are like poisoned baby formula. Later, in “Musings (Random),” he presents a tragic narrative in three phases: the era of Homer, in which man beholds his handiwork with awe; the Industrial Revolution, in which man’s growing estrangement from nature prompts nostalgia and longing; and the era of the Cold War, in which man can no longer think to look toward the natural world, for he has used up its symbolism: “We can no longer dream of the moon as seen / Among passing clouds in the sky . . . The moon is half-trampled.” The trajectory of the modern world is drawn as one in which we understand ourselves less and less, existing more and more in a simulated world of information.

At the same time, however, Wirpsza illustrates that humanity is not only the source of destruction, but of creation. To engage with poetry or music is to engage with a human byproduct, and in acknowledging this, the poet eschews the romantic symbolism which looks directly to nature to understand the soul. Instead, he contends in “No Paradise” that the soul cannot exist in Paradise (defined in the Dantean sense of a state of complete unity with God and goodness) as the soul is found in its very estrangement, its exile, from Paradise. He thus posits Paradise as the obliteration of the soul and the ego, as an existence of unchanging bliss without time or identity: “The past, present, and future / (As well as many other times and quasi-times) / Wage a battle with each other / In a tense seizure of con- / Currence thus happiness, heaven, love.”

Music and dance are proximate to the soul and the world in that they are always in motion, predicated upon time, change, and contrast; yet they also contain a potentiality toward the ecstatic and transcendent, however brief, and multiple poems throughout the collection touches on this possibility of sublimity. In the aforementioned “Apotheosis of the Dance,” Wirpsza concludes the poem by grappling with his role as a relatively anonymous writer in exile, locating his literary aims in the portrayal of a mythic “idiot” who gives himself over to ecstasy purely for the sake of the ecstatic. In doing so, it is he who executes the highest form of art:

The idiot

Did not dance a cancan; he wore black, spot-

Less tails. No one watched his show, though he

Juggled six-times-six swords won ages ago from the knights

Who had pursued him and now were lost who knows where,

Yet throughout the neighborhood their horses’ hooves thundered

And the cadence of the cancan came down from the heavens.

Wirpsza also sees this wonder enacted through the eyes of others; “A Monologue by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart” is an epistolary poem constructed with fragments of a letter by the titular composer, and in it, Mozart imagines an alternate reality as an anonymous “UnMozart.” Through this thought experiment, he experiences both ecstasy and dissolution, addressing egoism as a frivolous pursuit. One can surmise, then, that the “apotheosis” of art is an ecstatic ego death, wherein the artist inhabits the soul’s estrangement while despairing and gazing at this fallen world with open eyes.

It is on this basis that poetry, the ultimate act of human expression, is sourced by Wirpsza in mourning; grief has the power to bridge over exiles both temporal and geographic, holding states of horror and love together in pure, human union. In “A Woman Dances on Her Parents’ Grave,” the poet depicts a woman in a state of enraptured movement. When asked: “How do you know this field / Is your parents’ grave? Did you bury them / Yourself?”, the woman simply responds: “I did not. I am dancing.” The poem then goes on to list a series of places, any place, where a human body may be buried:

What

Country is this field in? France, Spain,Poland?

. . .

Where

Are you dancing? On the Baltic, the Mediterranean,The Red Sea?

Yet the woman refuses to answer, as the location of her parents’ corpses is irrelevant—just as it shouldn’t matter where the atrocities have been committed; we should declare the whole world a grave. In Wirpsza’s view, the proper site of mourning—and therefore transcendence—is simply wherever we grieve, wherever we are compelled to find meaning in despair, compelled by horror into motion. The final lines of the poem, then, are as much an ars poetica are they are a promise:

I will never die. I will dance

Long as there are candles and candlesticks, long as electricity

Powers the organs, oceans, and the land.

Katherine Beaman is a writer and civil engineer from Texas, currently living in Brooklyn. Her literary criticism can be found at 3:AM, DIAGRAM, Korean Literature Now, in addition to the website Commonplace Review, which she manages.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: