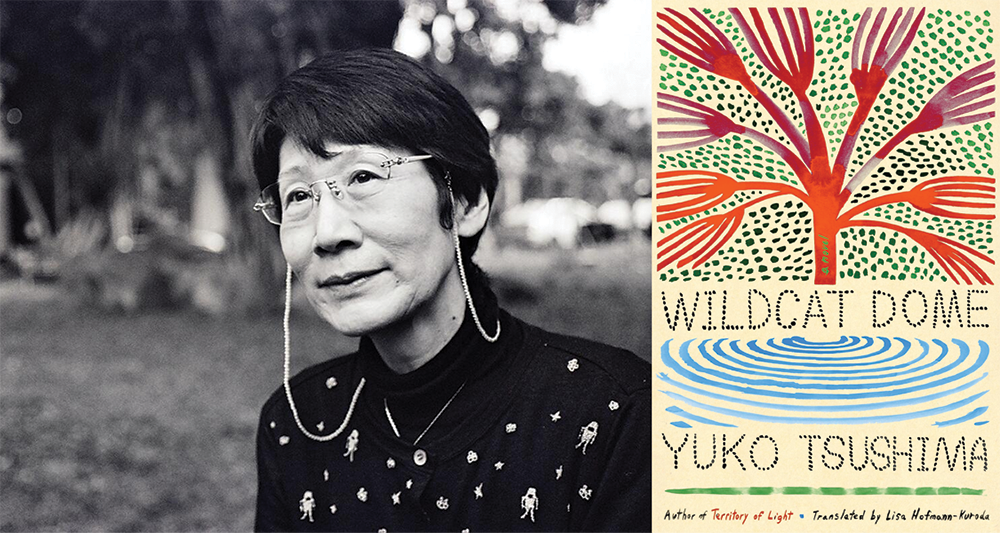

Wildcat Dome by Yuko Tsushima, translated from the Japanese by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025

Yuko Tsushima, perhaps one of Japan’s most quietly radical literary voices, is best known to English readers for Territory of Light and Woman Running in the Mountains—her early, semi-autofictional novels made up of domestic scenes of motherhood and explorations of non-reproductive female sexuality. In her later works, however, she turned away from the spare style that characterized her early work and towards larger-scale examinations of post-war Japan. Her newest book in translation, Wildcat Dome, in a graceful translation by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, introduces English-language readers to these powerful historical reckonings.

Originally published in 2013, in the wake of the tsunami that triggered the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Wildcat Dome is both a sweeping epic and a thoughtful meditation on memory, grief, and the unfinished business of history. Told through shifting narrative voices, the novel starts with a buzzing energy: a swarm of scarab beetles consuming leaves in an eerie forest, their appetite so immense that “time flows on and on, a river of emerald.” It’s a place where “insect time” collides with human time, and the buzzing doesn’t stop.

At the novel’s center are Mitch and Kazu—two children born to Japanese mothers and American GIs, then abandoned at an orphanage—and their friend Yonko, the niece of the woman who runs the orphanage. Throughout their lives, the three children, now adults, carry with them the weight of vague memories and a diffuse “prophecy.” This cryptic warning seems linked to a traumatic event that continues to haunt them into adulthood: the mysterious drowning of a fourth child, Miki-chan, a fellow orphan. As witnesses to the event, their young ages and fallible memories keep the circumstances of her death shrouded in mystery. Was it an accident, a crime, or something else? What about the strange boy, Tabo, who, unlike Mitch, Kazu, and Miki-chan, is “fully” Japanese and has a mother who will do anything to protect him—including covering his potential crimes? As the novel investigates the contradiction between the relentless passing of time and the stand-still of a history that has not been properly addressed, the prophecy shifts and mutates. Its warning comes to function as a narrative refrain rather than a concrete plot device, keeping the three main characters forever anchored to their pasts, unsettling any attempt at closure.

The novel’s narrative voice also shifts and changes; narrators slip between Mitch, Kazu, Yonko, and other minor characters, and memories surface in fragments, out of order, often overlapping and contradictory. This unstable structure mirrors the novel’s central concern: the unreliability of memory and the mutability of “truth”. At times, characters seem to put words into each other’s mouths or misremember events altogether. “In truth, it was your own voice you were hearing,” a narrator says, blurring boundaries between self and other, past and present, speaker and listener.

As mixed-race children in post-war Japan, Mitch and Kazu are seen as inherently suspicious, marked by their difference. “Even now, there were people who suspected them of being involved in Miki-chan’s death,” the narrator reflects. In contrast, Tabo, born to two Japanese parents, avoids accusation though he may well have been involved in her drowning. Mitch and Kazu, and, the novel implies, other children like them, are “left behind”—by their American fathers, by their Japanese mothers, and by the nation itself, with the children’s presence in the country viewed as an unwanted reminder of the humiliation associated with the American occupation.

As adults, Mitch, Kazu, and Yonko begin to question what they saw, what they failed to do, and whether someone—or indeed everyone—might have been responsible. “What was it we actually saw?” one asks. “Why didn’t we try to help Miki-chan?” The longer the event remains unspoken, the more it mutates into myth and rumor, as dangerous as any formal accusation, implicating the orphaned outcasts as murderers. “The shadow of a rumor never disappears,” the novel observes. “It warps, bends, propagates on its own accord.” The woman who runs the orphanage, Sister Yae, eventually adopts Mitch and Kazu. Alert to the ways society will cast blame on any reminder of the American occupation, she sends Mitch and Kazu abroad to escape the weight of judgement. And just like Japan has never fully acknowledged these orphaned children and their part in WWII, the three main characters fail to deal with their collective trauma—and as a result, the ghosts of the past grow bigger and bigger.

The atmosphere of a post-war Japan still bearing the wounds of American military occupation is crucial to the novel. The eponymous dome—a reference to the Runit Dome constructed by the U.S. on the Marshall Islands to dump the residues of nuclear testing—can be seen as a symbol of abandonment, of lives built in the ruins of a war that left some children and parts of history unclaimed by either side of the conflict. The legacy of this history, buried and undealt with, buzzes beneath the surface and eats away at society, like the scarab beetles devouring the leaves on the trees. The children’s parentage renders them outcasts in a society that refuses to acknowledge the legacy they represent, and so they live on the margins of a society that never fully accepts them. The dome, simultaneously scarring and sacred in their memory, becomes a kind of refuge for the nation’s displaced ghosts, both literal and symbolic. In this landscape, history itself is something unstable—remembered, misremembered, or actively forgotten.

The Fukushima nuclear disaster acts as a catalyst to unearth these histories: when Mitch, living abroad, hears the news, he is prompted to return to the Japan he has avoided for decades. He moves into an apartment once owned by Kazu—now deceased though, due to the novel’s nonlinear chronology, present in the story as both a living character and a narrative voice. As he does, pieces of the past begin to surface, disjointed, unresolved, and full of gaps. The footage of the tsunami and the exploding reactors ignites something dormant: “Distant memories, long submerged inside him, begin to wiggle and squirm as though irradiated.” The media’s phrase “tsunami orphans” opens a deep hole in his psyche, connected not only to Miki-chan’s death but to his own dislocation and identity, so intimately tied to the bombings that were the first nuclear disaster in Japan, the American military occupation, and the underlying, racialized suspicion that has long clung to children like him and Kazu.

The novel’s depiction of memory is inseparable from trauma—personal, national, and generational. Mitch’s return to Japan after decades of self-imposed exile is folded into a longer historical continuum, linking the Fukushima nuclear disaster with Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which form the backdrop of Mitch, Kazu, and Yonko’s childhoods. Radiation—its violent atomic instability—acts as a metaphor for this unresolved history. It lingers invisibly, mutating and decaying, transforming what it touches, and it outlasts any human efforts to contain or suppress it.

Tsushima is subtle yet unflinching in her indictment of Japan’s collective amnesia regarding its past and the aftermath of war. At the same time, she acknowledges the futility of what-ifs:

What if the girl hadn’t been standing by that pond alone? What if she hadn’t been abandoned by her mother? What if the American GI had never met her Japanese mother? What if the American GIs had never set foot in Japan? What if Japan had never gone to war? The mother had asked herself these questions hundreds, no, thousands of times.

The implication of these recurring questions is clear: the characters’ personal traumas are products of larger geopolitical events and Japan’s refusal to fully confront that legacy. The novel doesn’t frame Miki-chan’s death and Japan’s nuclear disasters merely as historical tragedies, but as an ongoing moral failure.

This can be seen most clearly in one of the most devastating motifs in Wildcat Dome—the chasm between children and adults, a gap defined by secrecy. “Children can’t just go around asking questions of adults,” one character observes. “Adults are always on guard against children, keeping them far away from their secrets.” In this way, Tsushima portrays adults as emotionally shut off and too broken by the events of the past to protect the next generation. This leads to a profoundly ironic scene in which the children play at war, impersonating American soldiers, ignorant of the significance of such behavior because no one speaks about this history. Children, perceptive and silent, learn to navigate around these absences: “children notice, careful never to get too close to those secrets, either.” In the past, as no one intervened to stop the rumors about who might have been responsible for Miki-chan’s death, silence itself became a form of complicity, passed from one generation to the next: “Each day it got harder and harder to broach the subject… and as time dragged on, it only became more difficult to speak about.” Time, in Wildcat Dome, doesn’t heal—it congeals.

Thus, when Yonko wonders, as an adult, “What was it we actually saw?” she’s not just asking about the drowning; she’s interrogating the entire architecture of adult and collective memory. But as the Fukushima disaster brings on memories from the past and makes it impossible to ignore their ghosts, these children, now adults themselves, are forced to confront their own histories, whether they want to or not. “Secrets never stay hidden forever. It’s only a matter of time,” it says. “That’s the scary thing about them.” Sooner or later, Japan and the novel’s central characters must all confront their past in order to move on. The congealment can only be temporary and perhaps this is the generation, and novel, to start the conversation.

As form and content work together in this way, the novel unfolds not with decisive clarity but with dreamlike uncertainty—its power lies in what it withholds as much as what it reveals. Tsushima’s prose is sparse and restrained yet evocative, confronting Japan’s most uncomfortable legacies—imperial violence, racial marginalization, postwar abandonment—not with grand statements or sweeping generalizations (although, as the translator Hoffman-Kuroda acknowledges, the racial imagery at times does rely on stereotypes), but with nuance and emotional depth. The disjointed structure mirrors the thematic concerns of the novel—fragmented memory, submerged trauma, historical denial. Just as the characters struggle to remember (or to forget), the reader is made to inhabit the same disorientation.

But it is perhaps also here that Tsushima risks losing some of her readers. The complex narrative structure makes it hard to follow who’s narrating and what actually happened, forcing readers to attempt to keep track of who’s speaking and puzzling together the timeline. This is clearly done on purpose, mimicking how memory works, but it occasionally delays the novel’s emotional impact.

While Tsushima’s earlier works like Territory of Light centered on the intimate struggles of women on society’s margins, Wildcat Dome expands that lens, confronting larger, structural forces and their impact on personal lives and memories. It is a ghost story of sorts: one that insists that we sit with the past. In the end, Tsushima’s style demands a reader willing to surrender to ambiguity. For those who do, Wildcat Dome offers hard-earned rewards: a novel that grieves, remembers, and accuses in equal measure—without ever raising its voice.

Linnea Gradin is a freelance writer from Sweden, currently based in South Korea. She holds an MPhil in the Sociology of Marginality and Exclusion from the University of Cambridge and has always been interested in matters of representation, particularly in literature. She has also studied Publishing Studies at Lund University and as a writer and the editor of Reedsy’s freelancer blog, she has worked together with some of the industry’s top professionals to organize insightful webinars, develop resources to make publishing more accessible, and write about everything writing and publishing related, from how to become a proofreader to whether you need a translator certificate to be a good literary translator. Catch some of her book reviews here and here.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: