Translation is a give and take—whether translating poetry or history, the questions of how and what are determined by the mode. In the following essay, Linnea Gradin discusses Linnea Axelsson’s Ædnan and its translation by Saskia Vogel, an epic poem detailing Sweden’s colonial history in the Sápmi region, the dislocation and cultural erasure of the Sámi, and the effects thereof upon culture and lineages. In an astute and personal analysis, Gradin calls for Sweden to reckon with its past.

In October 2024, the twenty-five finalists were announced for The National Book Award, an award spotlighting some of the most groundbreaking literature of the year and one of the biggest accolades in the English publishing scene. Amongst the five chosen finalists in the Translated Literature category was Linnea Axelsson’s Ædnan, an epic poem originally published in Swedish and Northern Sámi in 2018, now in Saskia Vogel’s translation.

Following two Sámi families over the course of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, Ædnan explores the dislocation and cultural erasure of the Sámi, traditionally semi-nomadic reindeer keepers who live in Sápmi, a region that spans “from the forest snow to / the windswept shore” in the north of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and parts of Russia. At the outset of the novel, we meet Ber-Joná, Ristin, and their sons Aslat and Nila at Lake Gobmejávri, close to the point where Sweden, Finland, and Norway meet. They are moving their reindeer herd across a familiar landscape, guided by a knowledge passed down through the generations:

We heard

heartbeats in the groundFaint

beneath the inherited

migration paths

Ber-Jóna and Ristin are later forced to settle on a plot of land assigned to them by the Swedish state that, due to the dams and power stations that today are so emblematic of Swedish green politics, is slowly but surely being swallowed up by the rising river, leaving the family unable to drive their herd across the land as they used to. As time passes, settled families are obliged by the state to send their children to residential schools, the forced assimilation casting them as outcasts amongst those Sámi who maintain the reindeer lifestyle—a conflict that becomes both a lasting divide within the Sámi village and a linguistic weapon for state lawyers years later, in contemporary time, as court hearings proceed to determine who has the right to reparations and the land. Thus, with Ædnan—an old northern Sámi word meaning the land, the ground, and the earth—Axelsson draws a picture of a systemic process familiar to many indigenous peoples across the globe: displacement, cultural and linguistic erasure, and the loss of a way of life. This is a tale that Sámi people know all too well, yet one that most Swedes were never taught in school, and one that hasn’t entered the wider narrative about Sweden as a state.

The international success of Ædnan arrives on the heels of a wave of Sámi-centered and Sámi-authored literature in Sweden (see, for instance, Ann-Helén Laestadius’ young adult thriller Stolen, which was also adapted into a Netflix film, Elin Anna Labba’s award-winning nonfiction The Rocks Will Echo Our Sorrow, or Mats Jonsson’s graphic novels, not yet translated). Together, these stories contribute to a nascent conversation about the cultural erasure of Sámi people in Swedish media and the relationship between Sweden’s indigenous population and the state, garnering energy from other global indigenous movements calling for reparations and climate policy action. By winning the country’s most prestigious literary award—the August Prize, named for playwright August Strindberg—and now being highlighted by the National Book Award committee, Ædnan marks not only a newfound push in Sweden to reckon with a colonial past, but also a truth-seeking and reparational literature that is becoming part of a global vernacular.

But in bringing these histories into a global conversation, the act of translation is always a negotiation between languages and cultures. In the case of Ædnan, it is the apex of three cultures, originally written in Swedish, simultaneously published in northern Sámi, and now rendered in English. The push and pull of linguistic expression and cultural fluency call for both textual and political changes, and the translation itself begs the question: how does language constrict and embolden how we tell histories?

In Swedish, Ædnan is a veritable brick. Clocking in at about 760 pages and written in verse, it must have been an intimidating project to take on even for the bravest Swedish publishers—not to mention in translation, as publishers can no longer rely on readers’ prior knowledge of historical details (though, arguably, the same can be said for most Swedish readers). Perhaps that is why the English version is almost two hundred pages shorter than the original. In an article in Words Beyond Borders, translator Saskia Vogel notes that the two hundred page difference was the result of two things: the first, formatting.

In the original, there is an abundance of white space, something Vogel says both mirrors the northern Swedish tundra and is an assertion that “this is not the definitive Sámi story.” The margins leave (literal) room for interpretation, in which we hear echoes of history and the displacement of other indigenous peoples around the world.

In Swedish, the start of each chapter is given its own page with a roman numeral as the chapter heading and a note at the bottom to indicate location, time, character, or some other detail to orient the reader. With a blank page between the chapter heading and the body of the text, the verses themselves are spaced out with some fifteen to twenty lines on each page, each line never longer than a handful of words, leaving gaping margins around a compact stream of words running down the middle, like a river. It’s a declaration of sorts: “I am here to take up space, to take up time. Slow down. Read each word carefully as you turn the pages. Sit with this story, as I and many before me have sat with it.”

This concept—the weight of a few words—stayed with me as I read the epic, first in Swedish then in English. I recalled a stereotype held in Sweden, that people who live in the north are fåordiga (directly translated as “few-worded” but more comfortably translated as “reticent”)—a perception that is somehow enforced in this novel, despite its length; making me wonder if the stereotype might be true, or if this brevity is perhaps the result of the near erasure of the language. Regardless, where words are few, the blank spaces resound with possibilities and subtext.

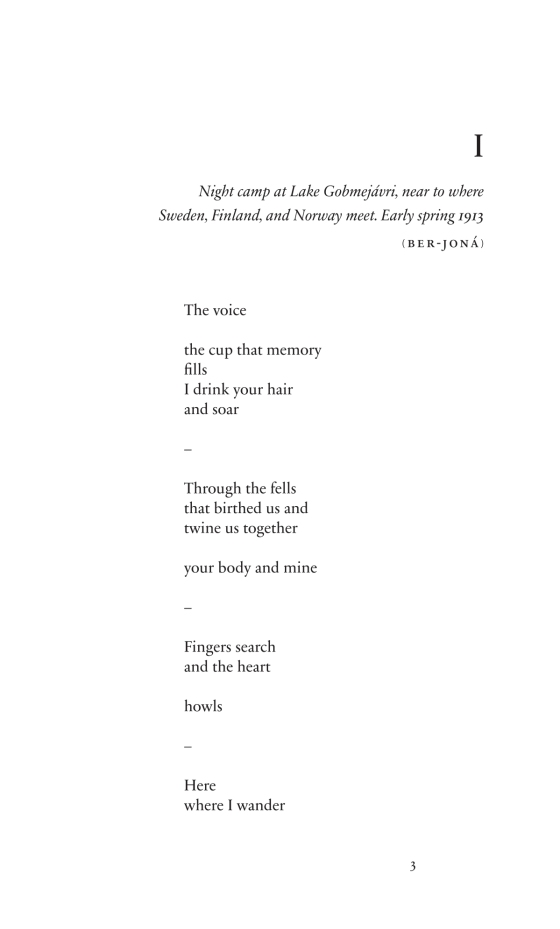

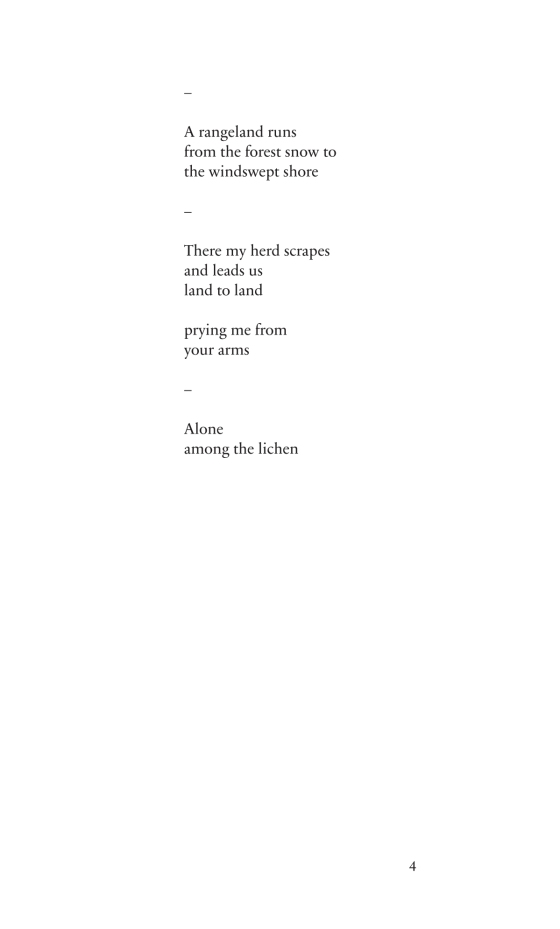

The English presents distinct changes: chapter headings and the orienting notes appear together at the top of the page, followed directly by verse. The blank space between lines is narrower, resulting in a first chapter that is no longer six pages, but two. As these changes add up, the length of the manuscript is significantly reduced. It is possible Knopf, the American publisher, had a hand in this—an epic poem in translation is a hard enough sell, and a seven hundred page tome runs the risk of intimidating readers and hiking production costs.

That said, what may seem like small, technical changes can impact the way the story is told and how it is heard. Take the first chapter again. In Swedish, words like “howls” sit alone at the top of a page, and the final stanza of the chapter sits in a sea of blank space on a page of its own. The same chapter in English appears as follows:

As I read the English, the impact of this howl and the lonely figure among the lichen is different. Not lesser, but also not the same. The Swedish “hoar”—the sound an owl makes—has become “howls,” probably because “hoot” just doesn’t carry the same sense of gravitas. “Here where I / wander” has been reorganized into “Here / where I wander,” isolating “here” rather than “wander.” Beyond these minute changes, however, the story stays largely the same. I might have had a much bigger issue with this change of form, as a reader, were the writing not as loud and sparkling as in the original, and if not for the fact that many of these reductions seem to have been made by Axelsson herself.

In a collaborative and reiterative process, Vogel and Axelsson “sat next to each other, editing line by line as far as [they] could.” Axelsson redrafted various sections of the text, cutting parts that, with hindsight, she no longer felt the text needed. As I compare the two texts, I notice the rearrangement of a word here, and the removal of another there. However, as is the nature of such a collaboration, it is impossible to tell who changed what; the question becomes not of what the translator did to the text, but how translation called for it to be remade.

All that said, it feels symbolic in a way: that the space Ædnan is allowed to physically hold is reduced when entering the global conversation. Heavily involved in the translation, Axelsson has largely been able to control how she wants to be heard in English and how she wants to tell her Sámi story to an international audience, but there’s also an irony to it: that in order to amplify this tale (as naturally happens when translated into English) she has once again had to negotiate the space she is allowed to occupy.

How are our tracks

ever to be heardAmong the Swedes’

roads and

power stations(p.211)

Going into my reading of Ædnan, like many Swedes, my prior knowledge of Sámi culture was limited. The history and topics that the book covers were never taught to me in history class and are rarely discussed in national news broadcasts. In this sense, my starting point was not much different than that of international readers, with the exception of my familiarity with Swedish politics and the landscape. However, while the teaching of Indigenous histories may be limited in places like Canada and the United States, my impression is that it has come further there than it has in Sweden—a country otherwise known for its progressive politics—where we are just now starting to talk about our full past.

In an interview on Swedish television following her win of the August Prize, Axelsson was asked whether “we” are more interested these days in “the time and history of the Sámi people.” She responded that she supposes that there’s more interest, but that “there has always been a lot written about the Sámi by others, often in a derogatory way.” She notes, however, that the root of the interest seems to have shifted, making Sámi art less of an exotic subgenre and more part of the wider cultural industry. And yet, whenever there’s a “we,” one has to pause to wonder who is included. In Ædnan, Axelsson does not shy away from distinguishing between “the Swede” and the Sámi.

Even as I’m writing this, I notice myself fumbling with the pronouns: the us and them. Where do I stand in all of this? A southern Swede who can count the times I have stepped foot further north than Stockholm—a six hour drive from where I live yet not even half-way up the country—on two fingers, writing an article about Sámi art. My knowledge of Sámi life, art, and politics used to begin and end with the brief glimpses I got of the Sámi news before switching back to the nationwide broadcast, where the virtues of clean energy are touted without acknowledging the cost to Sápmi in developing that industry.

You Nordic children

who have gone forth

so lightlyAs if you were

entirely without power

without a past–

Those who have

gone before you

apparently

forgotto pack your baggage

Having never really been taught about Sámi culture or history—and all too eager myself to experience a life outside of Sweden—it’s hard not to feel that the territory that Axelsson charts is more foreign to me than South Korea, where I’ve spent the last year. The narrative of indigenous displacement will be more familiar to some American readers than myself, in theme if not in texture. Even in Swedish, I find myself needing to translate place names and experiences that Axelsson writes about into words and images I can understand, transposing what I know from other places.

Today, the things I know about indigenous experiences and the resources that I reach for to interpret Ædnan are almost all borrowed from abroad; from American scholars like Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Kimberlé Crenshaw, or authors like Tommy Orange and Billy-Ray Belcourt; from reports about human remains in unmarked graves and residential schools in Canada, to critiques against the show Yellowstone, and the annual discussion surrounding Halloween costumes.

Up until very recently, many people thought that these were conversations and words that did not concern Sweden—problems that we did not have. Racism, colonialism, cultural erasure. We’re quite good at this in Sweden: decrying Jim Crow and gladly discussing the rights and wrongs of Thanksgiving, while never quite stopping to wonder why a Swedish hockey team named “Frölunda Indians” was allowed to keep its discriminatory logo and name for decades.

So, in Ædnan, when a character notes that “the Sámi didn’t have it as hard as indigenous people in other countries,” it’s at once a moment of great ambivalence and an astute observation of how we often look abroad instead of within. Even taking that as true, other countries’ sins do not erase what Sweden has done. Indeed, so many of the trespasses and violations of the Swedish state onto the land, onto ædnan, remain largely undocumented and unacknowledged precisely because it was supposedly never quite as bad as in other places. Yet Axelsson’s writing serves as documentation of this ongoing tragedy: of how Sámi children and adults were poked and measured, studied and categorized, and sent to “nomad schools” to “assimilate.”

In royal ink

that racial animal

was drawn. . .

And the shame

–

took root in me

Sámi people were taught to hide their heritage, which silenced a whole generation and created a culture of shame and secrecy that is only now starting to be dismantled—only now that so much has already been lost and forgotten. The comparison to other countries’ colonial histories has made it easy for Sweden to avoid facing its past; never quite as bad as others, the Swedish state upholds its reputation of progressive politics and social wellbeing, both internationally and domestically, in news and in literature alike.

But the era

of progress

and the world’s

consciencedoes not contain

the full

history of their land–

Our land

of course is one

they’ve never

even seen

I’m struck by the irony that I, someone who has indeed never seen Sápmi, turn to English to make full sense of Ædnan, not to Sámi scholars or Swedish history books. Theory can be clunky when transmitted across linguistic borders and into new cultural contexts, and the gaps lead me to view each culture through the lens of the other. In this sense, the conversation that Ædnan encourages is at once intimate and much broader than a dialogue between the Swedish state and Sápmi; it suggests that translation is not as one-directional as it might sometimes seem. As we read stories from across the world, we oscillate between languages and experiences to understand. We compare and contrast to find familiar patterns and systems, and see ourselves in the lives of others. That is how a story about two northern Sámi families living in a remote part of Sweden has resonated this much with readers across the globe. These ideas, that in Ædnan seem to stem from some deep, primeval place at the bottom of the ocean, from beneath the migration paths, from the silence of the mountains—through translation, echo into the blank, unwritten spaces that are drawn within and between our languages, first in Swedish, now in English, and beyond.

Linnea Gradin is a freelance writer from Sweden, currently based in South Korea. She holds an MPhil in the Sociology of Marginality and Exclusion from the University of Cambridge and has always been interested in matters of representation, particularly in literature. She has also studied Publishing Studies at Lund University and as a writer and the editor of Reedsy’s freelancer blog, she has worked together with some of the industry’s top professionals to organize insightful webinars, develop resources to make publishing more accessible, and write about everything writing and publishing related, from how to become a proofreader or editor, and whether you need a translator certificate to be a good literary translator. Catch some of her book reviews here and here.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: