I. Annunciation

My house was the site of an extraordinary occurrence. After my mother died, a gray cat walked into my bedroom and peed under the bed.

It came in while I was packing and looked at me like we were old friends. I shouted for it to get out and my heart skipped a beat. I had to leave the room. I watched it from the hall—it was serene even though I was trembling. It scrambled up onto the bed and sniffed my luggage. It wouldn’t leave—my exasperation and theatrics had no effect on it. It made itself right at home on the mattress. I came back with a broom to threaten it with, but I knew that if it just sat there, or if it tried to hide, there’d be nothing I could do. It dove under the bed. There’s no getting it out from under there, I thought.

It was one in the morning and I was pacing the living room, intimidated by this stalwart animal’s corpulence. I saw that the kitchen window was open, and the flowerpots on the ledge had been knocked over. “It came through the window,” I said out loud.

The cat meowed in the bedroom—it seemed to be in heat.

(The world’s noise sometimes makes us shriek inside and we suppress it.)

The cat stopped at my bedroom door to lick its chest. Then it went into the kitchen and escaped.

I know when the city becomes still. It happens between three and four in the morning, and it lasts barely a few minutes. It’s the time when no one is doing anything, silence’s moment.

Ever since my mother died, my nights are full of thoughts. I go to bed tired, sleep for a few minutes, then wake up trembling. I am not sick. I want to escape. I yearn for the force that will lead me to do it.

I think about trying my luck in my mother’s country, but then I doubt myself, because I wouldn’t feel right there, so I decide to travel abroad.

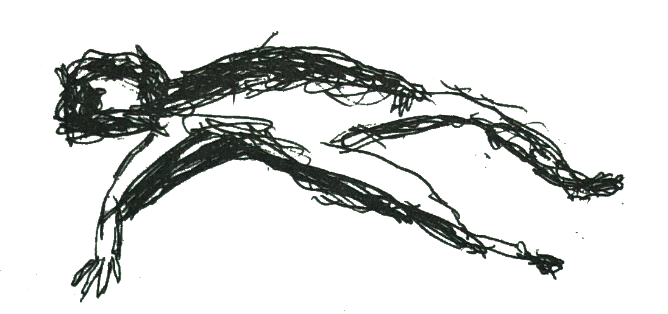

The way out isn’t built from articulate thoughts—it’s desire in its pure state: running like a hunted animal.

My mother’s face when she died was no longer a face. Her cheekbones had sunk into her flesh and the oval of her complexion had flattened out into a crown atop her hardened body. My mother’s mouth was a slit in green-tinged skin. Before the cremation, I gave her a kiss on the forehead.

It’s been weeks and this image’s terrible clarity still isn’t fading.

I will save myself. The force that’s driving me to go is the exact opposite of death. I’m escaping to put distance between myself and loss. This morning, when I got out of bed, I had to lean against the wall. I get dizzy.

I don’t want to be in my body—my hands are heavy like the claws of an animal that has just fought for its food. My eyes don’t perceive brightness in color. This afternoon, I heard a voice inside me that wasn’t mine. I’m surrendering my sense of thought to someone who speaks to me but whose face I can’t conceive of.

It comforts me to think I can find relief by going elsewhere.

I am going to sustain myself on the secrets I keep. I know that my flesh has powerful attributes—I don’t know what they are, but I base my certainty on true facts: my capacity for adaptation and the dexterity with which I have survived in critical situations. My body sometimes conceals its agility. If I want, I can be speedy and escape danger. Of course, what I’m talking about is inescapable. I feel the weight of my body and its vigor is real. I am going to gain vitality when I inhabit this elsewhere. The changes in my system are already underway.

These shifts are also occurring in my brain, spontaneously. I have a new, different perception of the world, and, at least once a day, there’s a spasm in my head, like what you feel when something has a strong emotional impact on you. I’m starting to be fascinated by the opportunities this new reality affords me. My muscles, which used to obey my every command, have gone lethargic, and, to compensate for this loss, I now have greater flexibility in my extremities. If I try, I can bend my arms far enough back to cup my shoulder blades in my palms without the least pain or tightness. And I’ve gone bandy-legged—my knees have abandoned their former unwillingness to bend left or right.

II. Rage

“I’m going to the airport,” I tell the one-eyed woman working at the taxi stand.

When she starts driving, I look at the street to make sure I’m really moving forward.

Then, one hand took another hand. My mouth kissed her forehead. I can’t give in. Death and transfiguration: the young woman’s hand on a dead woman’s forehead. My mother, invincible, died. Gods die.

In the distance, I see the airport’s fence and the bleachers where people watch the planes taking off and landing. Seated, soft drinks in hand, they watch metals occupy the sky.

I think that one of them will see the plane I’m on. One of them will know that I fled.

Movement doesn’t leave prints. Progress doesn’t scar. The streets I know cease to exist for me, starting now. I cover my tracks as I go.

My mother disappeared because her body turned to smoke.

In the sky, sleep comes. There is going to be a teenager beside me for the next ten hours. I don’t want to talk to anyone. I hope they think I’m mute. Instead of asking for tomato juice, I’m going to point to the carton and gesture for one; I’ll put my hands together in supplication instead of using my voice.

A video with cartoon characters explains what might happen in the event of a water landing. The characters: a woman and a little boy, Asian and white, moving like they have springs in their limbs and smiling as they act out the emergency.

Smiling in an emergency has its place. Smiling saves you—it’s a soft denial that humans just accept.

The teenager takes a music player from her bag—she puts in the right earbud, and then the other earbud, and then stretches; she’s happy.

I twist as deep into the seat as I can to get some rest.

The sky doesn’t seem the same when you’re flying on an airplane, it’s lighter, less palpable. “The sky is never palpable,” I murmur, my eyes puffy from sleeping.

I make mute-woman gestures at the flight attendant. She looks at me and doesn’t know if she should respond in kind or if she should talk. I let her flounder in her uncertainty.

The teenager wiggles her feet, which are clad in embroidered socks.

I don’t know much about the space outside. I’m looking through the airplane window and thinking about black holes. Dimensions are the brain’s membranes, we just don’t know it. My brain trembles like any other living being’s, but still, it frightens me to acknowledge it: something is growing in my head. I guess my mind is proceeding in an unexpected way; I can’t predict its patterns because I don’t know what I will experience in the future. No one does.

I traverse the clouds and nosedive to just the right altitude to see: a woman walking down the streets near her house; from the air, the woman is even smaller and her movements are lost in the distance. She’s going to the bank to pay her phone bill. She goes around the edge of a park and keeps walking. Either this woman doesn’t have a face or I can’t make out her features from this altitude. She stops at the street corner, waiting to cross—the bank is on the other side. She looks around and sees the other pedestrians who are waiting with her. Something I notice from up here: the woman is afraid of the others. Her fear prompts her to place her purse under her arm and cross the street without acknowledging the man who is trying to hand her an envelope. The woman doesn’t see him, or she acts like she doesn’t see him, and keeps going. The man just stands there with the envelope in his hand—he doesn’t chase after her. He tried but he didn’t succeed. The woman gets in line. Now I’m closer: I see her temples throbbing and I can practically watch her blood pressure rising. It’s Mercedes, my sister.

I hadn’t realized it, but her hands are young; she’s nervous—every minute or so, she looks cautiously over her shoulder. She tells the man behind her in the line:

“Did you hear what I said to the teller?”

“You said something to the teller?”

My sister makes an admonishing gesture and adds:

“Oh, of course, you don’t understand either.”

I wake to a ding in the cabin. The fasten seatbelt light is on. The flight attendant reiterates the light’s request and says that the aircraft will be experiencing turbulence due to inclement weather. My seatbelt is fastened; I hadn’t thought to unfasten it. I will get off of this plane safe and sound.

My sister Mercedes lived elsewhere but, from time to time, she would recognize that elsewhere was imaginary. Mercedes wanted to avoid the decay of her own insides. The world she saw was an Earth she quaked all on her own.

My mother was deboning a chicken for lunch, so she wasn’t able to stop my sister, though I don’t know if she would have anyway.

Mercedes had wanted to die since she was young. I don’t care to remember now that I’m far away—I don’t care whether Mercedes was ever dead or alive.

After the fall, the world was dark like she’d imagined. Mercedes opened an eye but saw nothing. She felt her body losing weight and her bones becoming lighter—she must have smiled, knowing she was about to die. Relishing these new sensations, she heard sounds that she couldn’t identify, heard them tugging at her: it was the magnetism of the sky enveloping her dispirited body.

My sister raised birds within herself and they pecked her insides to tatters. That’s how she described it to me.

Her suffering inspired me to resist. Our blood has to survive.

I will surrender to myself, to my thoughts. In the final hours, faced with the forcefulness of this new future, I have concluded that I will lose the memories.

I have decided to have a happy life.

When I peeked out the window, I saw that we were no longer flying over the ocean. I saw the earth covered with trees.

III. I Dream of the Jungle

I couldn’t sleep for several days before getting on the plane. I’d get dizzy whenever I moved my head, I ate just enough to not starve, and my skin started itching like it was sunburned. I called my friend Felipe and told him what was happening to me, but he said it was so soon after my mother’s death that my malaise was natural. I didn’t think my symptoms were a product of grief. It wasn’t just the pain of accepting that my mother’s time to disappear had come; my body was strange to me—it possessed a vitality I couldn’t explain.

Over the course of the previous month, I had observed, with enormous surprise, that my eyes were becoming slightly larger: I felt a certain tightness that I couldn’t describe—it was like the puffiness you feel when you first wake up, except it would stay there all day.

On my last night at home, I had a fascinating dream that strengthened my resolve to flee.

I knew that I couldn’t halt the changes to my body—I did not govern it, and in my dream, I confirmed my convictions: I moved on all fours through a swamp whose smell was lodged in my nostrils. Years earlier, when I was visiting the jungle to the south, I’d gone to a mangrove forest, where I was overwhelmed by the smell of rot; it emanated not just from the trees, but also from the living things, which were trapped in a perpetual cycle of decay and birth. In my dream, I crawled on the ground, over the twigs, leaves, and dirt. Most confusingly of all, my body moved faster than usual. Or rather, it moved in a different rhythm. The trees seemed overwhelmingly big, so big that I—or the thing I wanted to be in the dream—couldn’t see their tops; I was small relative to my surroundings. At one point, the dream felt so real that I was frightened, and I nearly woke up. But between sleep and wakefulness, I remembered that it was just an illusion, calmed my fear, then returned to the dream. I continued crawling, sinking into the boggy ground; I again took joy in the landscape of the jungle, listening attentively to its noises. I stopped when I felt something uncomfortable on one of my arms, and as soon as I looked at it, I shot awake: I did not see the arm I’d had all my life, but the leg of another being, of a different species of animal.

My mother liked cats. She never had anything new to say about them, just the same old: she’d talk about how quick they are, how well they can balance, the way they can prowl around all the fragile items on a shelf without knocking them over. She also liked to leave the door open so they could go out and experience the world, because they always came back home eventually—sometimes they were a little worse for wear and sometimes they were starved half to death, but they always came back and my mother was always proud.

When I was describing my dream, I didn’t mention how happy it made me to dream of being in the jungle—there was a joy in occupying that space, it felt like somewhere I had been happy once.

My own house produced a deep fear inside of me—that’s why I felt like I had to flee. In my moments of panic, the contours of things were threatening: the corners of furniture, the unevenness of the staircase, the outline of the rooftop (which had a vague, jagged appearance in my mind): the rooftop was the first thing I thought of—I peeked through the door and stretched my neck to see how high it was—I didn’t look because I thought it was a risk, but looking did make me see that the rooftop was a risk. I wasn’t thinking about throwing myself off it, but rather that it, on its own, represented a threat for me.

My fear increased when I remembered Mercedes’ illness. If we had both grown in our mother’s womb, shouldn’t we take after each other? Our carnality terrified me. But later, I regained my strength and stated my plans out loud—I repeated “I’m going to leave” over and over, like an incantation.

Meanwhile, my body kept making me feel strange things: I seemed more elastic than I used to be—I confirmed this when I was sweeping under the bed (after the cat’s visit) and succeeded in folding myself in two—my legs had become extraordinarily flexible, and I was able to return to one hundred and eighty degrees without the slightest effort. The dizziness, however, was worse in the afternoons, and I started experiencing other ailments: my hands started aching early in the morning—I can only compare the feeling to the very few times I did really intensive work in the kitchen, like cleaning shellfish. I started feeling a needling sensation in my knuckles, and I got in the habit of submerging them in hot saltwater for relief. After a few days, I accepted that pain, since it usually dissipated after I’d been up for an hour or two anyway.

The weather in the city was changing—the lightning storms were starting.

I think that losing consciousness was key. Otherwise, I would have chosen to undress and get in bed to sleep the day away.

I know I did everything you’re supposed to do before taking a trip; I had enough momentum in me to sort out the practical matters: I bought a ticket that afternoon, I packed a suitcase that night—I was restless even before the visit from the cat, because as I was washing the knives, I was afraid they might cut me; it was like they had a life of their own—I sat down to take a few breaths and to clear my mind of that idea. Then, out of nowhere, an image came to my mind: the wild was surrounding me; I fell asleep—the dream had announced itself.

*

In hindsight, I’m surprised I was brave enough to board the plane. I don’t know how I took such a long flight without feeling even a little panic.

The inclement weather has passed. Good time to go to the bathroom.

The passengers on the plane are sleeping.

The airplane bathroom is occupied by a tall German-looking man—I stand by the door, waiting.

Something I don’t understand is happening to me. I wouldn’t have even noticed it if it weren’t so overwhelming: I smelled my urine and it has a different smell than before—it’s sweet.

I eat the piece of chicken the flight attendant brings me. It’s in a sticky sauce. I hope I don’t have trouble digesting it, because my digestion has changed, too—my body’s natural processes must be impeded by my grief.

On the food cart there’s a glazed pastry—I also eat that. While it’s in my mouth, I look at the skin on my hand. I look at each of my arms—I’m wearing a green, short-sleeve T-shirt, and its color kind of reflects onto my skin. I have a thought—I don’t know where it came from, but I would transcribe it like this: “Soon, the skin on your limbs, your face, and your womb will be useless to you.” After that thought has run through my mind, I feel the itching in my limbs again—I scratch heartily and come to the conclusion that the agitation that causes this itchiness, among other things, is not going away. I try to sleep a little.

When I wake up, I look at my skin and see that it’s whiter, and I think it even has a different consistency.

I pinch myself and rub my hands together. I don’t feel things as intensely as I did before. My sense of touch has diminished.

The teenager wakes up—she had an enviable little nap.

I see that the skin is coming off my arms in places.

The place I’m going is by the sea. There are fewer and fewer trees there as you approach the coast. Trees stay away from the sea because they can’t grow in sand.

IV. Death

I have arrived at my destination, to my relief.

I buy a train ticket at the airport kiosk. I get a coffee.

I must have fallen asleep as soon as I sat down on the train because I don’t remember when it started moving. I think there was an old woman with arthritic hands sitting across from me—her hands were like my mother’s. Her hands were on her womb when she died.

I lifted her from the bed; she was thin and you could tell death was close from the temperature of her skin. She asked me to carry her to the bathroom so she could pee. The last liquid to leave her body mixed with the chemical blue toilet water.

In that trickle, my mother shed something delicate and vital. Her pee smelled like camphor from the medication.

Death was inevitable: pain, then. “My mother is dying; my mother is held in place by white pottery. Even if you just scratch at the smooth surface, she will die,” I shouted at Mercedes, who was resituating the pillows on the bed.

My mother, in her final moments, said she was being lifted off the ground.

She said other things, too; gibberish from the earth in her mind, which was starting to dry out. She’d lost the water and now the fish were dying: my mother swallowed mouthfuls of air and slowly contorted her mouth. She ached for the exhalation she hadn’t been able to achieve for months; she wanted to die breathing.

When her body went empty—her muscles suddenly lost their tone—she put her hand over her womb and squeezed her lips together. Then she released them, and Mercedes and I heard a faint sound: her final expression was a groan.

From the corner of my eye, I watched her dying like you watch a thunderstorm: there was a silver flash of lightning on my mother’s neck, and its magnitude and sound were fearsome.

Her skin changed after a few minutes. When the heart stops beating, the face becomes dehydrated and turns greenish.

My sister put another pillow under her head, covered her with a blanket, and repeated three times: “She won’t go anywhere anymore.”

*

In this new place, I am the only thing that exists; in my past, the dead are all that exist. I get a room at a cheap but clean hotel. I shower and take a nap. When I wake up, I look to the other side of the bed with disbelief: I am staring at a delicate piece of skin in the shape of my body’s contour; it has all my fingerprints and all my wrinkles; it feels like the glue I used to get on my palms when I was a little girl. I look at the skin, then take off my shirt to examine my torso. I don’t understand what I see: I’m swollen, and my pores are bigger, or seem to be; my complexion is a different color. I look at the skin again, grab it, and lightly run my hands over it. I recognize the chicken pox scars in the part that used to cover my forehead; I touch every inch of the skin, because I want to remember it clearly. This skin is my history. The whole piece is intact. I must have shed it with careful movements.

I put the skin in the trash can in the bathroom. I look at it there, lost forever, and I want to cry because there’s no one I can tell about it—my legs are trembling.

Before I fell asleep, I had wanted to go to the shore. After spending an hour in bed watching television, I put my things in my suitcase, which I take with me because I don’t know how long I’ll be gone.

I’m disoriented. I thought that the coast was to the north, but I’ve been walking for two hours and I don’t know where to go. I don’t want to talk to anyone. The prospect of engaging in conversation is terrifying. Anyone I talk to will ask what happened. My thoughts don’t obey me, they operate independently—it’s like someone is talking inside of me—and, even though I’m walking down the street where real events are happening, I can’t hold those events still in my mind. I’m in a state of sustained confusion.

A moment ago, I thought I was naked—I looked at my body and didn’t recognize it.

My skin still itches. I look at my forearms: they’re not swollen anymore, and the size of my pores has gone down—or, at least, I think it has. But in my muscles, I feel a new burning, which sometimes abates and turns cold. I scratch myself relentlessly, including on my legs.

I’m waiting for an unknown future, the same future as everyone else but with less grace. Either my ambition to escape was pointless, or the exit I took—whatever this thing that’s happening to me is—is the only way out left.

V. Respite

I want to climb up on a rock on the beach—I yearn to stay there until I need water. I go. I mount the rock because it’s only thing I desire now—I get comfortable—I understand that this will be my place from now on.

The sun warms me, and my body’s ailments subside. I look at my hands and notice that the skin on my wrists has thickened.

I came because here I have water and earth together. I can submerge myself in the sea whenever I wish, and I can step on land when I return. Both rock and sea are essential now; I wouldn’t know how to live any other way.

Shortly after arriving, I feel a tiredness that keeps me from writing down certain events—from bearing witness to them. I fall asleep.