In his 1940 essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History” Walter Benjamin tells story of a chess playing automaton. Dressed as a Turk, with a turban and the obligatory hookah in its mouth, the machine would impress with feats of competitive ingenuity. Unbeknownst to the crowd, a dwarf was hidden within its workings. An excellent chess player, he guided the automaton’s hand by means of stings. Originally meant as a critique on materialist theories of history, Benjamin’s allegory has been extended to critique automatism in general. In this enlarged formulation, the internet, for instance, is not a self-directed entity with a fixed set of properties but rather an aggregate of people and institutions using computer networks to advance a divergent set of very human agendas. Beyoncé might periodically win it, but the internet is no more a sufficient reason for human phenomena than any other factor, or so the argument goes. No matter how sophisticated the automaton, the human is always in some sense at the controls.

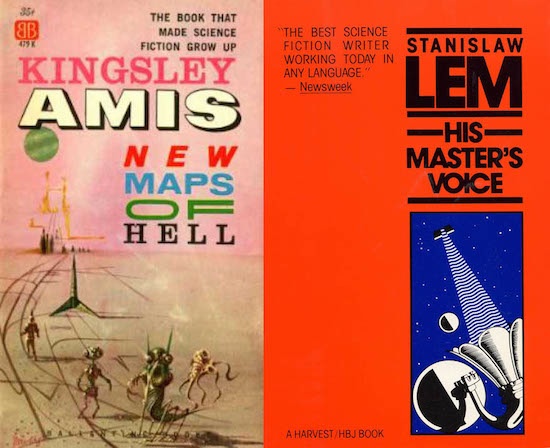

But how would the allegory change if the Mechanical Turk wrote instead of played chess? This is not idle speculation. Last year, the Associated Press used automated processes to write quarterly earnings reports for 3,000 companies, roughly ten times the number produced by human counterparts previously. Automated writing is not limited utilitarian forms like business news and product descriptions. The results, however, are decidedly more mixed. NaNoGenMo, the programmer’s version of National Novel Writing Month, was started 2013 by the Portland, OR based web artist Darius Kazemi. The object of the project is to complete a 50,000 page book by the end of November, only it must be written with software rather than the human hand. The computer generated novels are, as their programmers freely admit, mostly unreadable. Sustained narrative remains a problem.

Automated writing of the creative variety becomes much more convincing on a small scale. One standout example is Magical Realism Bot, an automated text generating program on Twitter, developed by the brother and sister team of Ali and Chris Rodley. Magic Realism Bot generates a different 140 character story every two hours, using random combinations of the various elements that define the genre: academic characters, mythical creatures, philosophical disputations, etc. The output can be amusingly absurd, such as “A fortune teller turns over a tarot card with a Gummi bear on it. Your destiny is to become a psychiatrist,’ he says to you.” But it can also resemble the work of real authors, at least in summary. “A learned society of mathematicians meet once a year inside a ruined synagogue to decide the fate of life on earth,” reads more like the scene from an Umberto Eco novel than the instantiation of a simple computer program.

Magic Realist Bot points toward a complimentary relationship that can exist between the modernist experiment in literature of the 20th century and the digital culture of the 21st. Both modes of thing involve subjecting language to intense analysis, natural language or machine language, taking apart its most basic components in the search for new modes of representing reality. Identifiable people still remain at the controls of these writing automatons, working as programmers rather than puppeteers, but the speed and sophistication by which these automatons fulfil their commands represents a difference in kind from past experiments in replicating human culture. Perhaps a new allegory is needed to replace the Mechanical Turk. Magic Realism Bot might very well generate one.

Ali and Chris talked to Asymptote about the technical basis for the Magic Realism Bot how that relates to how they engage with the practice of writing.

***

Matthew Spencer: Give us some background on yourselves. Specifically, I’m interested in how your efforts in social media, computer science and literature came to intersect.

Chris Rodley: I’ve wanted to be a writer since my early teens, and my literary heroes were the great experimental modernists like Woolf, Joyce, Brecht. Of course many contemporary writers of fiction and playwriting have turned away from this kind of bold, free-wheeling experimentation, maybe in part because where do you go after Finnegans Wake? This would sometimes frustrate me! READ MORE…