Seventy years ago today the British left the Subcontinent, and India and Pakistan became separate sovereign states. The Partition is often represented in terms of numbers—one million people were killed and twelve million became refugees. Visual artist Aanchal Malhotra has been making the migrants visible by recording the stories behind the objects the migrants brought to their new homes. One of the intangibles they carried were their languages. Asymptote Social Media Manager Sohini Basak sat down for a long chat with Malhotra to discuss her latest book that records these remnants. A very happy independence day to our Indian and Pakistani readers!

2017 marks not only seventy years of Independence of India and Pakistan, but also of the 1947 Partition, which saw one of the greatest migrations in human history. Close to fifteen million people were uprooted and had to migrate to or from India and the newly created nation, Pakistan.

In her book, Remnants of a Separation, artist and oral historian Aanchal Malhotra looks at the Partition narrative through the lens of the objects that the refugees brought with them as they made the journey. These objects were either the first things they could grab when they found themselves suddenly engulfed by communal riots, or things they considered essential or valuable as they prepared to settle in an unfamiliar land. Aanchal has also founded the Museum of Material Memory, “a digital repository of material culture of the Indian subcontinent, tracing family history and social ethnography through heirlooms, collectibles and objects of antiquity.”

I meet Aanchal in a café on a rainy afternoon in Delhi to talk about the languages she encountered while undertaking this curatorial project. After moving back to India from her studies abroad in 2013, Aanchal realized that in its race to be modern and in tune with the times, her generation—young, urban Indians in their twenties and thirties—often forgot to care about the items of the past. She started visiting historical sites every weekend and, from those visits and discoveries, extended the Partition project, which she started documenting on her blog. “I wanted to share the things I learned from people,” Aanchal says, when I ask her about the impulse that started it all.

Through her stories, Aanchal wants to tell the Partition story from a different perspective. The narrative of violence and trauma has been the overarching theme of the 1947 narratives, but she says that there are narratives of courage and friendship, and hope, too. Aanchal wants to revive these stories of “community and kinship and communal harmony” through the objects and their material history. And so she started visiting people’s homes in India, in Pakistan, and in the UK to look at and photograph things of the past. In the case of some of the owners of these objects—objects that vary from mundane lassi glasses and brittle refugee certificates to elaborately-stitched shawls and pearl necklaces gifted by royal families—it was the first time the owners were talking about their migration. Some of them had buried the traumatic experience of having to leave their homes, and after seventy years, they were finally ready to break their silence.

Trying to imagine the difficulty of this, I bring up Susan Sontag’s book, Regarding the Pain of Others, which starts with photography—also Aanchal’s medium. She tells me about an incident when two seemingly banal objects transported their owners to another time. She was then faced with a startlingly simple question: “How is it that a place that exists in one’s memory can also exist in their objects?” As she spent time with the objects, observing them minutely, listening to their histories told by the owners, sometimes it felt like “touching the place, the home, those stairs. You can only possess a certain moment by possessing something from it—either a memory strong enough or a tactile thing from that time.”

The way Aanchal writes the book—how she meets the subjects, how they change as they tell the story behind their possession, how they remember their family members, neighbors, and the kindness of strangers—paints the picture of intimate storytelling sessions. “I hate the word interview,” Aanchal tells me, even as I wonder if that was the word I had used in my first email to her. “People from a certain generation tell things in such ways that they become stories very fast,” she says. “With oral history, you have to understand that memory is unreliable, and that memory deteriorates with time. That’s a fact.” What makes this book intriguing is the way the original quotes are retained, and so, along with English, there is a good amount of Hindi and Urdu, and their varying dialects; Bengali; Sindhi; Punjabi. When I ask her about the reason behind this decision, Aanchal simply says, “I had to.”

Aanchal Malhotra (right) recording oral history.

Aanchal took the help of interpreters and translators, and curiously, she says that one of the most enriching experiences was when she conducted an interview with a Bengali couple, and she could not understand most of what was being discussed. “I did not understand anything. I had to wait for the translator, and then it was like fifty lines of Bangla turned into five lines of English. From a language that is expansive to a language that is brisk…”

Another episode recounted in the book may seem astonishing to readers. In Lahore, visiting a lady named Narjis Khatun, Aanchal could understand Samanishahi—a language she had neither heard nor heard of before until Khatun’s granddaughter, Bano, pointed it out to her. This moment of serendipity is one of my favorite moments in the book. I ask Aanchal to recall the episode and she remembers how Narjis Khatun did not speak to her for the longest time, but when she did it, was difficult for her to stop. Aanchal had not noticed the language at first, but did notice the difference in speech pattern. “Urdu is inherently glacial—the phraseology, that polish comes across obviously, and when put in contrast with something crude, that also comes across obviously.” Aanchal reflects on the language she had heard for the first time. “Samanishahi is a mixture of Punjabi and Hindi, and it’s very quick,” she recalls. The language is spoken by very few people in Samana, a place near Chandigarh, in India. Khatun’s granddaughter Bano added, “If my children have to learn where they come from, in the language that is authentic to them, then I will have to take them across the border where it’s spoken freely and openly.” Like the objects Narjis Khatun brought back, language acquired a materiality too.

Several of Aanchal’s subjects talked about language as possession, language as inheritance. A similar encounter happened when one of the people Aanchal interviewed—a Sindhi lady who left her home in Karachi on a ship to relocate to Bombay—proclaimed Sindhi as a dead language. “She marries language to land,” Aanchal said, recalling the conversation with Savitri Mirchandani on preserving a dying language. Punjabi has thrived because it is a part of India and Pakistan; Bengali has thrived because it is a part of India and Bangladesh. Aanchal recalls the poignant moment when Savitri said, “How has Sindhi thrived in India? It hasn’t, because we don’t have any land, we are stateless.”

Another subject, Lt Gen S. N. Sharma, who had served in the British-Indian army, talked about how young British and Indian soldiers posted in Kodaikanal, belonging to the Madras Sapperstroop, had invented their own language. They had a ritual wherein they would place a tumbler of water in the middle and take an oath of brotherhood, declaring that their language would from that point be that of the Madras Sappers. That would mean a combination of Hindi, English, Malayalam, Urdu, Punjabi and Kannada. “Where does that happen now?” Aanchal asks.

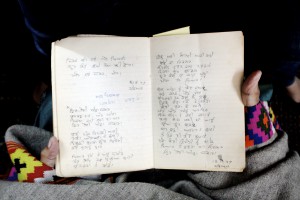

In Remnants of a Separation, I note that the most common objects that the 1947 refugees carried with them were utensils and jewelry. Essentials, valuables. What surprised me, however, were the occasions when the only objects some people carried with them were books, or notebooks. I ask Aanchal about these written artefacts. There is the story of the Guru Granth Sahib that a Hindu woman carried to Delhi from Rawalpindi because reading the verses in Gurmukhi gave her strength. And then there are the notebooks of poetry that the noted poet Prabhjot Kaur had carried and preserved. A teenager during the late 1940s, she wrote poems in Punjabi about those times. She and an army man started talking to each other by publishing poetry in a magazine, a series that grew as they responded to each other via poems. They fell in love with and later married.

Prabhjot Kaur’s notebook.

Prabhjot Kaur’s notebook.

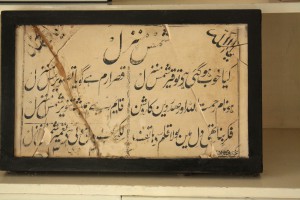

Most unexpected among the written artefacts, though, was a stone plaque from the façade of a house with poetry inscribed on it—without an address—that was carried across the border decades after the Partition and given back to the original owners as a piece of their erstwhile homeland.

The stone plaque from Mian Faiz Rabbanis’s home

The stone plaque from Mian Faiz Rabbanis’s home

in Jalandhar, Punjab (India) bearing the name “Shams Manzil.”

Unsurprisingly, the definition of “valuable” kept changing throughout the project, and sometimes, even during a conversation surrounding an object; as did the definition of possessions, and their materiality. A way in which cultural memory came to be preserved and passed on during this period of displacement and dispossession was by holding on to the memories of specific ways of living and doing things. Food became significant in preserving recipes and their seasonal variations. Noting ingredients used in making paan, for instance, was one way of recalling a homeland one had to leave. Clothing, down to the way it was stitched, was another. One such sartorial piece is the story that Aanchal writes about in her book, in a chapter titled the “Dialect of Stitches,” where the owner talks about the regional history of the cloth and of the phulkari embroidery through a shawl that was carried across the border. Aanchal tells me how, in stitching, women were “translating intangibles into tangibles.”

From the book, I gather that “Kuch nahi laaye the” (“We brought nothing”) was the first, almost-reflexive answer Aanchal received when she asked her subjects what they had brought with them during the Partition. And yet, in her narrative, Aanchal tells us that each displaced person had carried back something material with them—their language. In their use of certain dialects that may seem out of place, in the way they still used British Raj-era place names, or in their accents, lilting tones, slight mispronunciations—the book gives us a picture of the language of the lost homeland.

There are specific words that are used in the narrative of Partition, like the Bangla word udbastu, literally meaning someone forced to give up their bastu or homeland. There is, I recall while transcribing the interview, the Bengali poem Udbastu by Achintya Kumar Sengupta written about refugees. There is also the curious fact that unlike the often-used Hindi/Urdu word batwara (division, partition), there seem to be no Sindhi words to refer to the Partition.

I ask Aanchal how she trained herself to catch such nuances. She explains that as an artist she is naturally aligned to see the gradations of light and shade, the slightest movement, and when it came to listening to the stories, her attention was instinctively tuned to noticing the specific words used, the body language, and so on. She then declares that the book is “one hundred per cent dictated by the sensorial.”

Aanchal Malhotra is an artist and oral historian working with memory and material culture. She received a BFA in Traditional Printmaking and Art History from the Ontario College of Art & Design, Toronto, and an MFA in Studio Art from Concordia University, Montréal. Her work has been exhibited in Canada, the US, the UK and India. Aanchal lives in New Delhi and can be found on her website or blog. Remnants of a Separation is her first book

Sohini Basak’s debut poetry collection We Live in the Newness of Small Differences received the Beverly Series manuscript prize and will be out from Eyewear Publishing in early 2018. She is a Social Media Manager at Asymptote.

*****

Read more about Subcontinental languages: