Home and flux mean the same in a land named after a severance, or the great “partition” of the subcontinent: a paradox of freedom-and-loss, umbilical-cord-and-scissors. Born in Pakistan, a country that emerged on the world map after the collapse of the British Raj and the largest mass migration in human history, “permanence” is forever in the shadow of exile.

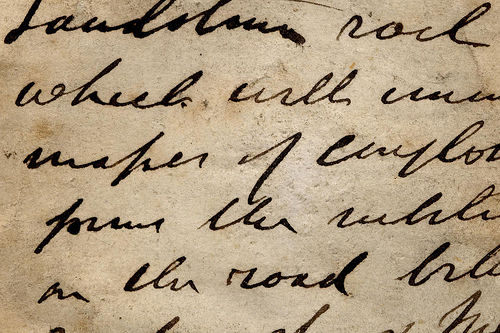

If poetry seeks who we are, I’ve found myself searching in language, not land. Land, in its aspects worth remembering, becomes language. If I carry language, I carry land. What is exile, then, if not a road paved for poets, permanent wayfarers?

I came to America as a college student. In Passage Work, the first series of poems I completed as my senior thesis at Reed, I wondered: why write in English, the language of the colonist? Have I taken language as a loan for poetry? Have I betrayed Urdu? In these earliest poems, I call language “luggage,” a historical-personal luggage, both burden as well as reason for being.

We may escape places, not histories—our histories are our tongues. My earliest poems had a bitter edge of postcolonial angst but the taste was well worth the discoveries yet to come. Not only did I get to dig out and sculpt in poems the loanwords that have come into English from Urdu, a gift to the Raj—words such as “khaki,” “jungle,” “pyjama,” “verandah,” “must,” “shawl,” “typhoon” and many others that arrest moments of the “jewel in the crown”—I also began to see Urdu more and more as a composite language, one that, when broken down, reveals that it is made up only of gifts, loanwords from other languages, itself a language of empire.

Urdu nestles so easily in divergent cultures and is capable of spectacular flights in poetry. Alongside English, with its lyrical powers, pliability, its special eccentricities, and a literary tradition that includes South Asian writers in its canon—both languages feel “mine,” not just because I grew up with them but because I share their wanderlust.

Where English brings together the Germanic and the Latinate sensibilities, Urdu combines the Arabic, Indic, Persian, Turkic ones—disparate civilizations colliding, falling into confluence over time. English and Urdu are languages with rich textures and tensions built into them, poetic tensions between the victors and the vanquished of diverse landscapes. From these tensions, the scintillating song of the human spirit, its struggle and celebration, memory and articulation, the grit and grandeur of history cutting windows of perspective in an unknowable future.

I left one country a daughter and became a mother in another. Thinking about language as history and inheritance, as empire and base of power structures, seemed weak in comparison to the power of giving birth to a child (and thereby becoming the custodian of a clean linguistic slate which presents the chance to bypass history perhaps and write down spirit by freeing myself of the luggage I’ve carried thus far). Could language be birth and growth? Could it be anything other than luggage?

The answers come slowly. I could not have predicted how a newborn would coax language out of me, how the first need to be filled by language would be to give comfort urgently, how soon all the music held by language would have to be summoned, how my first language with my child would be neither English nor Urdu, but a pidgin made up of both, in weaving and unraveling translations— tradition transferring, transposing on its own in these first, raw, desperate songs. I did not know that poetry hooks language the moment emotion takes over and that a clean slate ultimately writes itself, in exquisite ways, that even among the multiplied riches of language, I could, at times feel as an outsider in California where I’ve lived longer than anywhere else, where my accent is foreign even under my own roof, where my children sing in Urdu but debate in English, and take it upon themselves to coach me on stressing syllables the American way, to pronounce correctly words such as “umbilical cord.”

***

Shadab Zeest Hashmi’s Baker of Tarifa, a book based on the history of interfaith tolerance in Al Andalus, won the 2011 San Diego Book Award for poetry. Her poems have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize multiple times, and have been translated into Spanish and Urdu. She is the winner of the Nazim Hikmet Poetry Prize and her work has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Poetry International, The Cortland Review, Vallum, Nimrod, Atlanta Review, The Bitter Oleander, RHINO, Journal of Postcolonial Writings, Spillway, The Adirondack Review, and Drunken Boat among other journals and anthologies. She represents Pakistan on the website UniVerse: A United Nations of Poetry, and has taught in the MFA program at San Diego State University as a writer-in-residence. She is a guest columnist for 3 Quarks Daily. Kohl and Chalk, her new book, recently won the 2013 San Diego Book Award.