In the introduction to her vegan cookbook, Recipes for Peace, Kifah Dasuki describes her mission this way: “This is more than an ordinary cookbook, though. I wrote it in two languages—Hebrew and Arabic—side by side from a place of great love and with a real hope for change. A hope to fight fear and hostility and to nurture love and compassion.” For Dasuki, compassion is unconditional. Person to person, human to animal, language to language, compassion is fundamental to the building of a new world free of the “fear and frustration” she feels have been her lot. And this book is one building block she will contribute to the new world.

As she personalizes her recipes with anecdotes and reflections from her life, Dasuki isn’t shy about the challenges she has faced as a woman from the Arab village of Fureidis (which aptly means “paradise,” she notes, though in her darker moments she also calls it a “hellhole”) in Israel. She attributes her ambition and resilience to such challenges. Possibly her most vivid anecdote describes her first day of university in Tel Aviv, during which she encountered the word “proportzionaly,” a Hebraization of the English word “proportional.” As she didn’t know the word at the time, feeling inferior in her foreignness, she went crying to her dorm room. Later in the semester, she recognized for the first time how a difficult but honest dialogue between Hebrew and Arabic speakers can lead to mutual understanding. With this foundation, she began to actively bring people together for such conversations from all parts of the extremely diverse Israeli society.

The cookbook Recipes for Peace is the latest example of Dasuki’s success. She crowdfunded the Arabic-Hebrew original. In her own words on the experience: “We want peace so badly, but don’t know how to find it. The campaign’s success showed me what a powerful force people can be. Working collectively, we really can change the status quo.” The recipe book is divided into three chapters, each dedicated to a phase of her life. Sharing her story and views is as much a part of her mission as circulating the recipes of the tasty food.

It’s worth noting that in the original book, Dasuki travels a long way to meet her Hebrew-speaking audience. For example, while the recipes appear in both Hebrew and Arabic, the rest of the text does not. Having come a long way from the university student who was self-conscious about her language skills, Dasuki wrote the book in Hebrew and had her sister translate only the recipes into Arabic, leaving the personal narrative, so integral to her mission, untranslated. To me, these choices suggest that she sees herself as an emissary, representing herself to an other. She isn’t trying to tell the same story to her Arabic-speaking audience (a story which, she believes, they are already familiar with). So what is the purpose of the Arabic text? Is it symbolic mostly for the visual of the two languages side-by-side? Is it to entice Hebrew speakers to follow her example by reciprocally opening themselves to Arabic language and culture?

For this article, I asked Dasuki how she identifies her nationality. Palestinan? Arab? Arab-Israeli? Each term is loaded with political significance. She answered that she is done with the whole notion of nationality, and all the violence it has caused. She prefers to identify as a feminist, a vegan, and a native Arabic speaker. In the same vein, while working with the translator on the recipe for Moghrebieh, a stew made of maftoul (Palestinian couscous) and chickpeas, Dasuki asked if it would be possible to call the couscous by another name, for fear that the appellation “Palestinian” may seem too political. This radical effacement of the words that mark the nations as separate is in itself a deeply political choice with both positive and negative consequences.

Speaking solely from personal observation while living in Jerusalem, language is one of the many ways that the city delineates who is welcome where. Signs, menus, and products tell you in which part of the city you belong. Bookstores sell books either in Hebrew and English or Arabic and English but rarely all three. Students are kept separate (with a few notable exceptions) and are not expected to learn each other’s languages. This segregation is a huge topic of debate amongst those who want social change. A full discussion of the various arguments is way beyond the scope of this blog post, but suffice it to say that they depend on one’s satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the status quo, what sort of change one would like to see, and whether one is more interested in peace or in justice (or, I suppose, neither).

In this context, it’s laudable that Dasuki has successfully become proficient in the language of those she had to seek to understand, and that she has found an audience amongst them. And she calls on her readers to do the same: “Who knows? Maybe the desire to read the recipes in Arabic or English will inspire you to learn a new language.” Dasuki chooses to entice people into dialogue with visions of a rosy future and a mouthwatering spread. The real work begins once you’re all sitting around the same table with full, happy bellies. But what about these crucially important words and omissions? Can you draw everyone to the same table when your rhetoric caters to some and tokenizes or effaces others? I suppose there are many paths to such a lofty goal as peace, and I’m happy to know that Dasuki is out there walking one of them.

Recipes for Peace is forthcoming. As a teaser, though, I’ve selected for you a three-course meal. Enjoy!

Appetizer

Manaqish wo Labane—Pita with Za’atar and Labane

Makes 8 units

This dish brings to my mind the blue sky, the smell of the fresh mountain air, and the memory of sitting under an olive tree, dipping a fresh manaqushe in labane cheese—my village saturating my soul. Manaqushe (plural: manaqish) is a wonderful pastry that the name “za’atar pita” doesn’t do justice. And what can be better than a manaqushe slathered with labane? But now, as a vegan, I can’t be faithful to the original. Rather than bringing the village to me, I have to bring my new life to the village with a gorgeous, healthy and completely vegan labane. Almonds, cashews, garlic, and olive oil are flavors that make you want to sit again under the old olive tree, dreaming.

Ingredients

MANAQISH:

3 cups flour

1 tablespoon dry yeast

1 tablespoon brown sugar

1 teaspoon Himalayan (or regular) salt

1 cup tepid water

TOPPING:

1 cup za’atar, preferably fresh

1/2 cup olive oil

LABANE:

1 cup peeled, raw almonds, soaked overnight

1/2 cup raw cashews, soaked overnight

1/2 cup dried soy beans, soaked overnight

1/4 cup olive oil

Juice from 2 large lemons

1 garlic clove

2 cups water

About 1/2 teaspoon salt

Preparation

Preheat the oven to 200 degrees C (400 degrees F).

For the manaqish:

In a large bowl, mix all of the dry ingredients. Add the water gradually while kneading. Knead the dough for 10 more minutes, until it’s firm. Cover with shrink wrap and a clean towel, and let the dough rest until it doubles in volume – 60-90 minutes in summer, 2-3 hours in winter.

Spread flour on a clean surface and knead the dough, letting all the air out. Cut into 8 equal parts and form balls. Roll out to the desired size (I recommend about 15 cm (6 in) in diameter). Cover with a towel and let rest for 10 more minutes.

In a bowl, mix the olive oil and za’atar.

Using your fingertips, lightly press the surfaces of the pitas (to keep them from inflating). Brush each of them with olive oil and za’atar to taste. Take the oven down to 180 degrees C (360 degrees F), lightly oil a baking pan and arrange the pitas on it. Make sure to keep them about 2 cm (1 in) apart. Bake for 10 minutes, or until the inner part is light brown.

For the labane:

Use a food processor to blend all of the ingredients except for the water and salt. Add the water gradually while processing, until you reach your preferred texture. Keep in mind that the labane is meant to be relatively thick, but it tends to get thicker when refrigerated. Add the salt, taste and adjust seasoning. I recommend that you taste and adjust the seasoning again after refrigerating.

The manaqish is served on a wooden or straw tray with a plate of labane garnished with olive oil, olives and fresh vegetables. In winter, it’s best served with a cup of aromatic herbal tea, for the complete experience.

Main Course

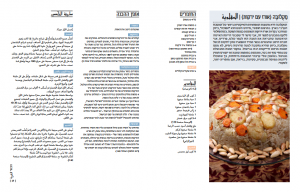

Maqluba—Rice and Veggie Upside Down Cake

Serves 4—6

The maqluba is one of the most splendid and iconic dishes of the Arab cuisine. Literally, it means “upside down,” because it’s a casserole of rice and vegetables served as an upside-down cake. When I started collecting recipes for this book, my father told me that my grandmother was the first woman to cook this dish in our village, Fureidis. I remember how the women in the village used to brag that they could cook maqluba, since they considered it a dish that requires experience, precision, and a fair amount of preparation in advance. Traditionally, it is cooked with pieces of chicken or meat, and served with cream or cooked yoghurt. For my recipe, I’ve made adjustments so you can enjoy a vegan version that is tasty, healthy and, I believe, more moral.

Ingredients

2 cups jasmine rice

2 small potatoes

2 small carrots

1 small eggplant

1 small cauliflower

1 tablespoon oil

4—5 cups vegetable stock

Salt and pepper

1/4 teaspoon turmeric

1/4 teaspoon ground nutmeg

1/4 teaspoon cardamom (optional)

TO SERVE

1/4 cup roasted almonds

Preparation

Preheat the oven to 180 degrees C (350 degrees F). Wash the rice well.

For the vegetables:

Peel and slice the potatoes and carrots, keeping them separate from each other. Break the cauliflower into small pieces by hand. You can cut big pieces in half. Slice the eggplant, salt the slices and leave them on a paper towel for fifteen minutes. When the fluids have seeped out, blot the slices with a paper towel.

Arrange the vegetables on a baking dish lined with parchment paper, keeping each type of vegetable separate from the others. This will make it easier to arrange them in the pot later. Brush them with oil and roast for about 30 minutes, until partially soft.

Arranging the maqluba:

Layer the roasted vegetables into a deep pot, sprinkling salt and pepper between each—first the potatoes, then the eggplant, the carrots and finally the cauliflower.

Pour the rice over the vegetables, then add in the vegetable stock and the spices. I recommend starting with 4 cups of liquid and adding more if needed—the liquid should be 1 cm (2/5 inch) above the rice. Using a long wooden spoon, carefully ventilate the rice by making 3-4 holes from the top of the rice to the bottom of the pan. This will allow the rice to cook thoroughly and the spices to reach all the layers.

Cook over a medium flame for 30-40 minutes. You can add a cup of boiling water as the rice cooks—the liquids should stay 1 cm above the rice until the cooking is done.

Let the casserole rest for at least 30 minutes before serving.

For serving:

Put a large tray over the pot, and carefully turn the pot upside down. If the maqluba doesn’t come out whole, like a cake, no matter—you can use my secret: rearrange the vegetable layers in the bottom of a deep bowl. Cover with the rice, gently compress using a large spoon, and turn over again. This time, the maqluba should come out whole. If not, don’t be disappointed—authentic Arab food is always messy! Maqluba is best served with a side of green salad or cold yoghurt.

Dessert

Kahk al-Eid—Ma’amoul

Makes 30 units

Kahk al-Eid, “holiday cookies,” are made of dough and filled with strongly spiced dates. They are also known as khak bajwa or ma’amoul, and are usually served on Muslim holidays.

Ingredients

DOUGH

1/2 kg (1 lb) semolina

1/4 cup brown sugar

1/2 cup flour

1/2 tablespoon baking powder

1/2 tablespoon vanilla sugar

1/2 teaspoon ground makhlab (optional, can be found in specialty spice shops)

1/2 cup non-dairy milk

200 g (7 oz) refined coconut oil

FILLING

250 g (9 oz) medjool dates, pitted

50 g (2 oz) refined coconut oil

1½ teaspoon ground anise

1½ teaspoons ground nutmeg

1/2 teaspoon ground cardamom

GARNISH

Caster sugar

Preparation

Preheat the oven to 180 degrees C (350 degrees F).

For the dough:

In a large bowl, combine all of the dry ingredients. Add the milk and coconut oil and knead until uniform (about 20 minutes). Cover with shrink wrap and let it rest in the refrigerator for at least an hour.

For the filling:

In a bowl, mix all of the ingredients and knead until uniform and easy to work.

To assemble:

Divide the dough into 30 small balls. For each cookie, press the ball into a rectangle. Using your pinky, make a dent in the rectangle and fill it with the date mixture. Close gently with your fingers and make sure the dough is shut tight. Arrange the cookies on a baking sheet lined with parchment paper and bake for 10-12 minutes, until golden but not burnt.

Let cool and, using a small sieve, garnish with caster sugar.

For variety: You can use ma’amoul tweezers to decorate the cookies with patterns and designs or add walnuts to the filling.

All the recipes were translated by Tom Atkins.

Lindsay Semel is the Assistant Director of Asymptote for Educators, an initiative that provides resources for educators who’d like to use Asymptote content in the classroom. She recently earned a BA in Comparative Literature and Arabic Language and Literature, and works alternately in education, sustainable agriculture, and freelance editing. She also enjoys yoga.

*****

Read more about food and literature: