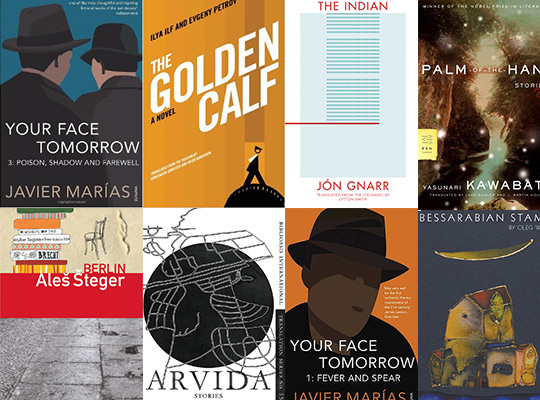

Asked to review my year in reading and from it form reading resolutions, my immediate response is something I need to call an excited sigh. For months now, as a judge for the Best Translated Book Award, all I’ve read are eligible books, books published in the US translated for the first time this year. Yet, there were a few months before that reading took over. For years now, I’ve taken pleasure in not being partway through any books when the new year begins, so as to open each year fresh. This year, Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov’s The Golden Calf (trans. Helen Anderson and Konstantin Gurevich) made for a great New Year’s Day read. (To call it fitting, however, would be a lie.) The novel is hysterical, absurd, and clever, fueled by ambitious and clueless characters, fleeing and bumbling in pursuit of fortune.

Taking advantage of a bitter winter, I read the Your Face Tomorrow trilogy from Javier Marias (trans. Margaret Jull Costa). It is rare for a project so vast to also be unflagging in both its entertainment and ability to find new shades and twists for its ideas: of cultural memories, of what it is to read another human being, of violence and intimacy. But this trilogy accomplishes it. From it alone, I could pluck a number of examples of one of my favorite narrative tricks: to make a scene continue endlessly through digression after digression. Unlike any other art form, the novel is thus able to manipulate the experience of time, both of the readers’ and the characters’.

But yes, this year has been a culmination of reading more and more books the year they’re published. The best way I can think about it is by describing the books that stand out in little, meaningful ways. Starting with where I live, in Vermont, so close to Montreal, Quebec literature has had much of my affection this year. Not just the translations, like the Raymond Bock and Samuel Archibald story collections Atavisms (trans. Pablo Strauss) and Arvida (trans. Donald Winkler)—so similar in their arc as collections and interest in familial depths but with different approaches and destinations—but also classics like the narratively unsettled Kamouraska (trans. Norman Shapiro). Anne Hébert’s novel is as much a story of a women trapped by culture and time, and her murder plot, as it is a stylistic achievement, melding aesthetic with the narrator’s psychology.

Yasunari Kawabata’s Palm-of-the-Hand Stories (trans. Lara Dunlop and J. Martin Holman) is a great example of the pleasure found in anecdotes that aren’t afraid to be epic in scope. Aleš Šteger’s Berlin (trans. Brian Henry, Forrest Gander, and Aljaź Kovac) was my deepest reconnection with that pleasure since Jansson’s eternally recommended Summer Book (trans. Thomas Teal). The stories recreate place so as to induce emotional reactions: longing, nostalgia, minor torment and peaceful stillness. It’s a style that is so tempting, because it seems so achievable but elusive; it is wondrous when done so well.

Mercè Rodoreda’s War, So Much War (trans. Maruxa Relaño and Martha Tennent) gave me one of my most memorable reading experiences of the year. I raced through it compulsively, fueled by caffeine and sun, horrified and in awe of beauty, so much so that when I finished, I walked around town, wanting to accost people with my thoughts, and to pressure them to read passages.

Oleg Woolf’s Bessarabian Stamps (trans. Boris Dralyuk) is another collection of brevity, but it stands out this year for its strangeness, for the way the stories flux between reasonable pastoral, and compelling nonsense, for the sentences that open towards predictable structure, so that when they veer suddenly, they seem impossible and wrong.

Jon Gnarr’s The Indian (trans. Lytton Smith), a playful and emotional autobiographical novel, pushed me to memories of those overpowering childhood emotions I haven’t had in years. Here’s a reasonable test: if child-you ever needed to just burn shit to make it through all-you interiorized, then this book is for you. If you didn’t, then it’s probably not. For making a twisted, overwhelmingly visceral gothic murder mystery also a wickedly funny satire from the 1970s, I’m appreciative of Gabrielle Wittkop’s Murder Most Serene (trans. Louise Lalaurie).

All of these translations, with the exception of Kamouraska, were published this year. Many of them I normally would have missed. So, after a year of reading based on the new, I want my reading resolution to take me elsewhere entirely. Two years ago, creating a list of five, just five, books to reread was my private reading resolution. It failed utterly. Now, I’m hoping that making a resolution public will help it stick. And this time it will be two-fold: reread some books without a list of defined ambitions; and read books first published some years ago and that I already own. For the first, even without making a certain list, I have to return to that old, failed resolution. Returning to failure seems to me a fitting tone for a reading-related resolution.

This year, I have more encouragement for one of those old names. Max Frisch is a writer I don’t hesitate to call one of my favorites, yet I struggle to recall specifics of his books, of what I loved so much; instead, I remember only a sensation that those books fit me, fit my reading desires and identity. As part of their dedication to collecting literature lovers to write about a specific author, an underappreciated subject, The Scofield selected “Frisch & Identity” for their spring issue. How could I not want to reread at last one of his books so that I can appreciate the contributions to that publication all the more?

Another failure of that lost resolution is Kōbō Abe, another I easily call one of my favorite writers, though unlike Frisch, I can say why. Abe’s protagonists are rejected by the world, and reject it. Out of that rejection, a new space is created, whether it be the dunes, secret levels underneath a hospital, a trip to the underworld, or an ark full of other rejects, hiding from nuclear apocalypse. Normal life, which hasn’t been comprehended clearly anyway, has been replaced by another life, odder, full of dread. Or at least this is how I think about his varied oeuvre years after reading it. A reread will put my thoughts to the test, and could happily see them destroyed, replaced by a new interpretation.

As for the other half of my reading resolution, to read books that are not recent publications: this could manifest as so many different authors, different books, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t at least commit to a few. Why not start with a confession, admitting an embarrassing gap in my reading? It’s time I read Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch (trans. Gregory Rabassa). Intimidated by its length and the near-demand to love it, I’ve stayed away. Knut Hamsun’s Mysteries (trans. Sverre Lyngstad), one of my top found-on-the-berm books is another on this not-list, my step beyond Hunger. I want to return to travel books, so should pull Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts off my shelf. Not so much a traditional travel book as an inventive satire of the genre, how about A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre (trans. Andrew Brown)? Keeping with the French, moving forward in time, to a writer whom, like Hamsun, I need to encounter more of, this year would be a good time for Julien Gracq’s Balcony in the Forest (trans. Richard Howard). I only know him as an essayist, with Narrow Waters, and want to see that mind and aesthetic at play in fiction. My final non-resolute detail of a resolution leaves translation. I’ll return to another writer I refer to as one of my favorites: Herman Melville. Only because of his books that I haven’t read, it’s the one sitting on my shelf, this year I should read Israel Potter.

Honestly, even if all the names change, even if I only read a couple of books fitting these descriptions, I’ll be happy. It’ll be a reason to pause in the reading, to take extra pleasure in patience, because I knew it was something I needed, and I broke off from momentum and habit of years of reading for a different, refreshing, direction.