What is the memory of reading? How do you remember reading? For me, I cannot simply recall the book in question, but also when I read it, why I had chosen to read it if there was a choice involved, or how I chanced upon it, and most significantly, where I read it: in which rooms and in which seats. I have moved around a lot this year, both travelling and relocating, but at the same time, my memories of reading certain books invoke stillness, the kind where you notice the slightest movement of daylight changing the hours. The off-white of the page and the off-white of the walls. The world outside the door. And you reading. And then there are some books that do not ask for a stupor, but an attention where you want to see or imagine it being made, you want to know what it looked like in its first stages and what conversations transformed it into its finished present state. Well-arranged poetry anthologies have this effect on me. When I heard Robert Chandler speak about The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry at the Place for Poetry conference, at Goldsmiths in London earlier this year, I knew I had to spend time looking at the way he had organized the contents and think back to what he had said about editorial choices, about being both editor and translator, and working with co-editors. How does one take on the challenge of representing 200 years of Russian poetry to be published in 2015 and under the banner of a Penguin Classic? The key, Chandler said was in striking a balance between what is available and what should ideally be available. So he had to go beyond the ‘seductive neatness’ of the four that most representation of Russian poetry is over-fixated on (Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Boris Pasternak and Marina Tsvetaeva), and include a few non-Russian poets, and have over fifty contemporary translators work on the anthology.

The best reading recommendations have come my way as accusations. How could you not have read Marguerite Duras? Really. How could I not have read La Maladie de la mort? So when I did, I read it two times in English and then one time in French. I should confess now that my French is not très fort, so the experience of reading the original text was more like ghost-reading, if ever there was such a thing, because I could recall the meaning of the translated sentences though obviously not their syntax. Short stories and novellas work the second person narrative intriguingly, and so I’ll make a switch: you know it’s a good book when you start reading everything that’s there in the library by the author, especially in the order she wrote them. You marvel at the small tricks the world plays on you when you find a thermal print due-slip a previous reader left behind, with a similar list of books you have on your nightstand.

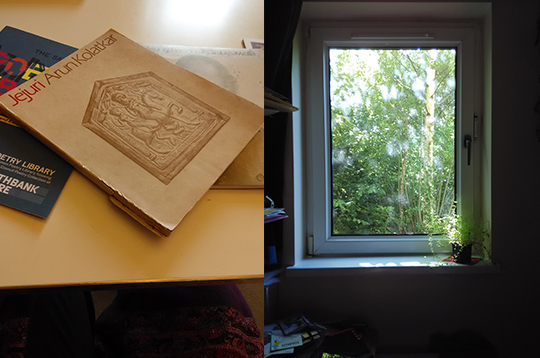

I have always been one for rereading. In fact, this year is more interesting as I have transitioned from being a literature-creative-writing student to a part-time reviewer to starting on my first full-time editorial job, roles that involve very different kinds of rereading. The eyes work differently, and the brain is made to function differently. But some of my annual rereading pilgrimages, to mostly books of translation, will remain unchanged: The Yale Anthology of Twentieth Century French Poetry, the complete and collected works of Cesare Pavese, Vasko Popa, Wislawa Szymborska (Map: the Collected and Last Poems was a treat this year), and Arun Kolatkar. Rereading Kolatkar involved another of those world’s tricks since it happened when I wanted to do a random check to see how many Indian poets the Poetry Library at Southbank Centre stocked (a fair many), and found the Clearing House first edition of Jejuri. It looked like a well-leafed-through-the-years copy.

I read very few novels this year, my prose-reading tastes have completely tipped over to the side of short stories and Lydia Davis when it comes to fiction, but mostly to diaries, correspondences, and creative nonfiction, especially writers on writing and reading. Of the few novels that I did read, Kenzaburo Oe’s A Quiet Life was remarkable. There aren’t too many valid reasons to compare Oe with Murakami, except the Nobel Prize have and have-not, and that they both are contemporary Japanese writers, but when you curate #worldlit social media news on a daily basis, you cannot help but wonder how any tweet with Murakami will invariably get the most RTs, and if there is a need to address the one author = one country representation in popular imagination. Oe’s novel was soothing to say the least, and it often reminded me of scenes in Hirokazu Koreeda movies with children having to grow up on their own, the tap running somewhere in the kitchen, the slow motion of the knife as it cuts through a watermelon and the palpability of guilt and grief at family dinners.

I have moved to a different city back in my country, am yet to find a room of my own, and miss having poetry books around. None of the books I have written about are within my physical reach, I wish I could browse some Russian poetry tonight, sitting amongst half-unpacked suitcases. A room in Norwich, a library seat in London, the hush of feet, plants staring, a sheet of glass keeping the cold and rain away, everything reflected and superimposed onto each other: stray lines from a novella, or someone who had mentioned it, everything against the foreignness of places you will not go back to in a while, the familiarity of languages you are used to hearing, often without understanding. I come back to the memory of reading. Maybe the memory of reading is a bit like the act of translation: it is a playful re-creation, there will be a sheet of glass in between which reflects and lets you see through simultaneously, but always there is the desire to feel the temperament of the wind on the other side, and then realizing that the sheet of glass could be a window and that the wind on either side will have its own cycles and its own currents.

Sohini Basak is a social media manager for Asymptote and has recently completed a creative writing degree from the University of East Anglia, for which she was awarded the Malcolm Bradbury Continuation Grant for poetry. She currently lives and works in New Delhi.