Text Shadow and the Moving Translation: An Essay by Laura Marris

When I began to talk to artists about translating poetry, I said I wanted to make a text that could contain multiple interpretations. A moving translation, which would shift and reform at the pace of reading. Matt Kenyon and I were at an artist residency in mid-February—everything in the landscape was snow-blind white. Not an image of a system but the movement itself, he said, pointing to my storyboard covered in scribbles. Like a stain. Injecting a dye to see how blood circulates.

Translating the heart of one language into the heart of another—a process that needs to create poetry, with all its movement and association and strangeness. The rhythms and sounds of a poem notate breath, or as Ben Lerner puts it, a fiction of collective breathing. The same notes played across the surface of each person’s brain, rocks skipped across a body of water. And then rippling in ways that are individual, unpredictable, private.

To put it more simply, if writers are observers of life, then translators are observers of language. Words, though they may seem static, don’t really stay put. Even in print they are still liquid, the way window glass is a liquid, whorled and thick at the bottom of an old frame.

“I never set foot/ in the same river twice,” poet Paol Keineg writes, and it’s true—for each poem in his book-length sequence Mauvaises langues (Bad Language) there is a slight shift in landscape, a view from another day in a familiar place, another layer of lived experience. This is the first book Keineg wrote when, after living in America for thirty-five years, he returned to Kimerc’h, Brittany, the town he grew up in. These poems of simultaneous homecoming and displacement mark the end of an exile.

Each day, a new version of the self. But the journey makes cultural and linguistic continuity difficult, which is a source of both humor and sadness. Keineg’s lines continue “because/ there was no river, and because/ I didn’t know how to swim.”

For translators, each gesture creates a new version. The medium of the page usually requires that we settle on one rendering, even though we may have considered hundreds of other possibilities before we arrive at the final text. The gestures of words expand, but often at the expense of other words. Which is another way of saying the translator must choose between possible shades of meaning. Almost every word in a poetry translation could be another word, each phrase could be another phrase. But what ends up on the page has won the argument.

One interpretation. Which can, of course, range from literal to wild, but I wanted to know what might happen if a translation was animated and faithful, if it was allowed to reflect the whole spectrum of meanings.

In the video, new versions of words and lines substitute themselves into the text. Instead of settling on one final version of the poem, the text remains unsettled, allowing a more complex portrait of a translator’s knowledge to remain on the page. This is not so much a process of revision as a process of recreating the state of mind that produces translated work.

Some words are momentary slips, while others stick for longer. The conversation between poet and translator remains visible. You can pause the video, fast-forward, manipulate it. As Matt says, the camera catches what moves too quickly for the human eye. The photographer Eadweard Muybridge supposedly settled a bet this way—how many feet does a horse have in the air at full gallop? The images make a flipbook when they are allowed to layer, like the animated words mimic the movement of a poetic line in a translator’s head.

Some lines can go in many directions. In the opening line of Keineg’s poem, “le retour au pays” could be personal or full of restraint, it could mean France, or Brittany. Homecoming, returning to your country, returning to this country, returning to my country, coming back. I limited myself to viable possibilities that fit the tone, so the formal “one’s country” never appears.

I wanted to work with Matt because his pieces react to the world, incorporating data to become reflections of the systems they study. His sculpture Cloud produces foam buildings that shrink or grow depending on housing prices. Then they float to form a ghostly development on the ceiling of the gallery. The real-time narrative of the housing crisis plays out in an artistic space.

Translation is also a process that permits the communication of stories.

Brittany, the region where Keineg grew up in the 1940s and ‘50s, has chafed under central France. Breton language and culture were aggressively repressed through French schools, where many people from Keineg’s generation lost their mother tongue. In school, French was the “good” language and Breton was the forbidden one. Keineg’s early political poems take on France’s oppression of Brittany, and the region’s historic resistance. Keineg writes primarily in French, but sometimes in Breton, and he often includes Breton words or phrases in his poems. The cultural landscape is suspicious of linguistic authority. In this context, I wanted to translate in a way that could accommodate shifting linguistic loyalties, rather than delivering one authoritative version.

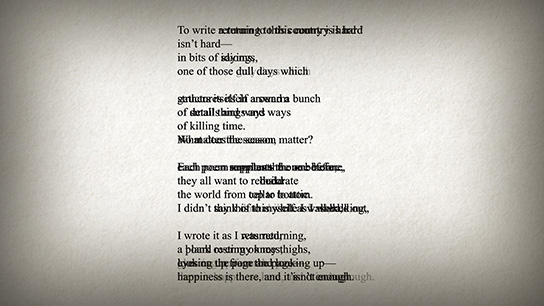

I chose this particular poem from Bad Language because it expresses dissatisfaction for completeness, and for static writing. Here is one rendering, from the original French:

To write that returning to your country is hardIt’s odd to see what another writer has seen, and stranger still to re-envision their imaginings. Even poetry critics who become experts on a text don’t usually assume they see the images exactly as the author did.

isn’t hard—

at the end of sentences,

one of those grey days which

gathers itself in a crowd

of details and ways

to pass the time.

What does the season matter?

Each poem displaces the one before,

they all want to remake

the world from top to bottom.

I didn’t say this to myself as I walked,

I wrote it after returning,

a board resting on my knees,

eyes on the page and over it—

happiness is there, and it isn’t enough.

Matt: Variability in interpretation is how we’re taught poetry. But it’s easy, when writing or translating, to get stuck in a Sunday crossword of poetic constraints.

Many translators would say it is impossible to be perfectly literal, which is not the same as saying a given translation is impossible. Nabokov’s translations of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin are the classic example of translated poems becoming a scholarly resource through an insistence on precise transfers of meaning from one language to another. These versions are necessary, but harder to read for pleasure—there is a sense that the engine of the poems has been dismantled, and every screw and sprocket and pump is laid out on the garage floor. The whole car is there, but it won’t run.

When I drove around with Keineg in Kimerc’h one summer, he pointed to the house he grew up in, to the place out back where the rabbit hutch once was. He showed me his elementary school, where, before he was even old enough to go, he saw a teacher hanging a student out the window by the ankles—a punishment for speaking Breton instead of French. There was the mulberry tree in his yard, the apples, the drifting clouds. The direct connection between place and image helped me to see the origins of the poems. But this process expanded my choices rather than narrowing them. I had the same basis of vision Keineg did, literally the same places and things, even if my sight was much simpler, much less layered with memory. From Keineg’s 2012 book, Abalamour:

bang bang these memoriesOf course, this transference is contestable when it comes to another’s individual consciousness. But if a poet makes himself vulnerable to a translator, if he allows the translator to move the pieces of the poem—and therefore the fabric of memory—then it’s the translator’s responsibility to do justice to the complexity of voice and place. Any really good poet won’t let you pin the poem down, whether it’s in translation or in a critical essay. Our goal is to offer the poems up, to provide printed versions and also pieces like this video—the text and the shadow it casts. The shadow that runs over the ground, over the landscape.

are rabbits

you pull out of a hat

and then hooray

The video is both literal and animated, grounded in a place and rising out of it. All of the choices are there in the landscape. The poem is there. And you can watch it breathe.