Works by both Koi and Hyungmee Shin featured installations of shoes with evocative writing inside, in Koi’s case plain blue shoes with unsent letters to friends and family in the North, and in Shin’s case, painted shoes with (also unsent) letters to Koi’s parents, describing intimately observed moments in their daughter’s new life. One of Koi’s pieces, Unit Harmony, is a large-scale mandala made of fabric folded like paper airplanes, each with a wish for peace written inside, another manifestation of the artists’ envisioning of Korean unification.

Koi takes her name from a fish that stays small in a small pond but grows to a great size, given the room. The exhibition is named after Koi’s age when she escaped to South Korea plus the number of years she has been in the country; the “ing” represents that her life in Korea is ongoing, still being created.

I’m grateful to Jiyu Seo for collaborating with me on this interview and translating it. Answers are from both artists, unless otherwise marked.

Koi, I was moved by the detailed description of your journey from North Korea, inscribed on the inside of shoes and addressed to your parents and your brother, in your piece The Reason For Walking Today. It is a powerful way to share the story of this perilous trip. Could you talk about the development of this piece, the significance of the shoes, and the response you had when you shared this work with the public?

Koi: For me, shoes represent movement and change, and the steps of one’s inner journey. In my work, shoes are not merely mundane objects, but media which represent the human journey and the weight of our personal resolve. Just as we put on shoes when setting out toward a destination, shoes symbolize beginnings or departures, leaving footprints, the traces of the time and experiences we pass through. The act of tightening and tying shoelaces when stepping off on a new path is, to me, more than getting dressed. It’s a ritual that grounds and reaffirms a mindset. In this way, shoes have become a key recurring and reinterpreted motif in my artistic practice.

The specific shoes I use are known in North Korea as pyeonrihwa (편리화; literally convenient or comfortable shoes), and are commonly worn by residents in daily life. For me, these shoes carry my memories and longing for the hometown, friends, and family I left behind, as well as the assurance that they still walk alongside me, in spirit.

The Reason For Walking Today (2025) is the second of my works using shoes. It takes the form of letters dedicated to my parents, tracing the journey I took leaving North Korea to finally arriving in South Korea. At the young age of nineteen, I risked my life to cross the border in search of freedom. Through my journey, I hope audiences are able to empathize with the lives of North Korean defectors, or more broadly, the experience of living as an outsider or stranger in a foreign land. At the same time, I wish for the work to serve as an opportunity to reflect on how precious and hard-won the freedom we often take for granted is.

Your work foregrounds your strong sense of mutual connection, shared vision, and the bond in your collaboration. Could you talk a bit about how you came to meet and how your collaboration has evolved over time?

Koi: We first met in 2013, as mentor and protégé when Shin was working as a psychologist for defector youth at the request of the Korean Methodist Church, while I was serving as the secretary of the organization. We kept in touch as mentor and mentee even after the group was dissolved, and in 2020, we began working together more formally.

Our collaboration first stemmed from our shared views on reconciliation and unity between North and South Korea. Art transcends language, becoming a means of expressing and communicating humans’ hopes and dreams. We hope that the visual messages we create will encourage more people to look at and reflect on ideas of Korean integration and reunification with sincerity. Furthermore, we believe that the process of working together holds even greater meaning/significance than the finished product itself.

Our process is centered around constant communication with one another. Throughout the creation of each piece, we always share our thoughts and ideas with one another, and even when disagreements arise, we make sure to respect each other’s perspectives. At times, these differences are directly incorporated into the artwork itself. After each exhibition, we always reflect together on what went well, what could be improved, and discuss directions to take in the future.

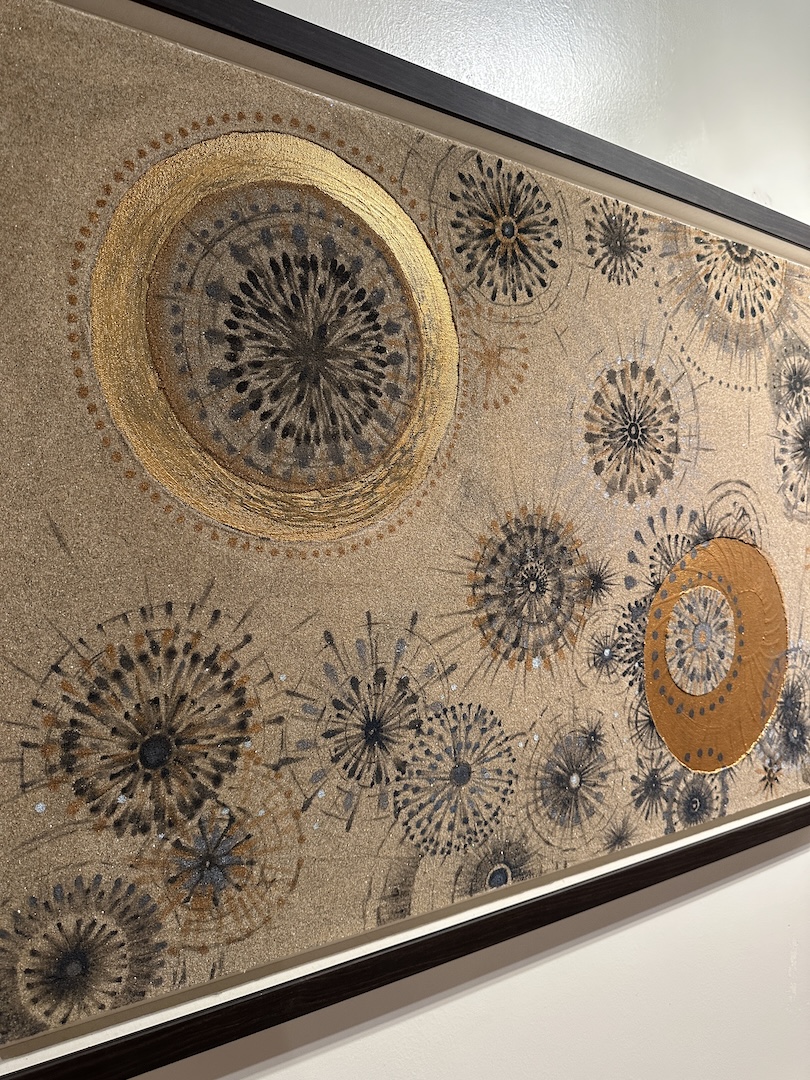

Could you talk a bit about Hyungmee Shin’s piece, Meet There, which uses sand as a material, and the inspiration for it? I know it’s based on the trip you took together to the coast near the border between North and South Korea, and the ways you envisioned what is shared between these two places.

We place great significance on the process leading up to the completion of each single work or exhibition, because we feel that it is through this process that our minds and perspectives grow and mature together. Before creating Meet There, we visited many places in search of something that both North and South Korea share. We observed the migratory birds and plant life that cross both borders, and the ecosystems of the North-South border area (남북접경지역). During this process, Koi began to open up more about her childhood and memories in North Korea, and Shin found herself moved by Koi’s longing, and took it to heart.

When we visited a beach in Goseong, at Gangwon-do Province (강원도 고성), Koi was reminded even more vividly of memories in her hometown, Chongjin, and at that moment, we came to realize that what North and South Korea share may be an emotion like Koi’s longing. And through that, we could faintly sense just how deep and enduring that longing truly is. As if we had made an unspoken promise, we both gathered handfuls of the glimmering sand from that beach and brought it back with us, and Shin used it as a medium to express the emotions we shared on that journey. Thus, Meet There is not just a record of our travels, but captures the deep longing we experienced and carried together.

Hyungmee Shin, Meet There [Detail], Acrylic and sand, 100 x 60 cm, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.

What were the reasons behind the selection and arrangement of the pieces for this exhibition? What should audiences take away by going through the exhibition in the way you intended?This exhibition begins with Koi’s shoe series. Shoes encapsulate Koi’s journey, from leaving her hometown to settling in South Korea, and the emotions on that path. The works that follow explore her longing and memories of her path, and the time she spent building a new life in South Korea alongside Shin.

Hyungmee Shin, The Time of Koi [Detail], Fabric and dye, 2025. Image by Heather Green.

From the early days of Koi’s resettlement, Hyungmee Shin has accompanied her, and her observations and documentation of Koi’s life naturally extend into her own work.The exhibition culminates in a collaborative project created jointly by the two artists. The structure of the show was designed to show each artist’s distinct artistic vision before converging into a shared space of collaboration.

Through this, we aimed to show how an artist originating from the North and an artist from the South share each other’s experiences and collaborate, expressing unity through the language of art. We wanted to portray Koi’s life and her process of resettlement in South Korea with honesty and sincerity. Instead of spoken language, both artists use the visual to translate lived experience into an accessible form for the audience. Ultimately, we hope to, slowly but steadily bring attention to the hope of reunification and harmony for North and South Korea.

I was intrigued by the many titles of the unique colors made by participants in your color workshop, and by the “sigma” painting of Korea, which draws on the shape’s similarity to the sign for “sigma,” which represents, as you say, “a summation of a series.” I noticed the bottle labels had evocative phrases, like “A warm pink wishing to be part of an ordinary day” and “Green of a new beginning.” Would you please elaborate a bit on this project, both the workshop, the color creation, and the use of the colors in this larger painting?

The project Communicating with Colors, which began in August 2020, features works created by over ninety North Korean defectors and South Koreans expressing their thoughts and images related to unification and integration by creating and naming their own colors. This project, which unfolded over eighteen sessions, holds great significance in sharing and communicating thoughts on the integration and unification of North and South through the expression of color, which is something we don’t often reflect on in our daily lives.

The process:

- Write your own “emotional mind map” about “the integration and unification of North and South.”

- Choose symbolic colors from the mind map and mix them.

- Give a unique name (title) to the color you felt through the mixed colors.

- Introduce and share your thoughts and feelings about your color with the group.

Koi and Hyungmee Shin, Communicating with Colors (Expressing the emotions of integration and unification through color), Acrylic paint, ongoing. Image courtesy of the artists.

Map of the Korean Peninsula Embraced by Sigma is a work created by Koi, who feels it is a shame that many people are unfamiliar with the map of the Korean peninsula. Each district or region of the map was hand painted by Koi and Shin using paints developed in the Communicating with Colors project.When the opportunity arises, we organize workshops titled “Coloring My Own Korean Peninsular Map,” in which participants use colors and paints from the Communicating with Colors project. The purpose of these workshops is to encourage participants to freely explore and reflect on the meanings behind each paint’s color, while engaging with the core message of the Communicating with Colors project in a creative and personal way.

I’ve noticed a distinct absence of direct political iconography in your works, such as flags or real-world figures. Could you share your intentions behind this choice, and what you feel is gained, or perhaps, avoided by leaving such imagery out of your works?

We believe that art should not be a tool for expressing a specific ideology or political stance, but rather a space for pure personal expression rooted in the artist’s life and experiences. For this reason, we have deliberately excluded references to political parties, doctrines, and political symbols from our work. What we seek to convey are not declarations for what is right and wrong in ideology, but an honest artistic expression of what we have lived, learned, and felt. Through this, we hope viewers will form connections not through political interpretation, but through our true lived experiences, and the artworks themselves, on that basis.

Koi, there’s this idea of “existence of resistance,” where simply continuing to live as an oppressed individual becomes a form of activism. You’ve spoken about not wanting to be defined by your identity as a defector but still wanting to advocate for unity. I’ve also noticed patches on your apron that might share this sentiment, like the ones reading “people over politics.” Could you share more about your perspective on this idea? Do you believe, or desire, to separate people from politics, or do you see them as inevitably intertwined?

Koi: As an artist from North Korea, I am aware that my background alone can easily invite stereotypes about political interpretations or ideologies, and for this reason, I have distanced myself from having overt political narratives in my work. While it is true that “North Korea” forms the backdrop of my work and practice, for me, it is simply my origin, where I was born and spent my childhood. Just as anyone might long for a place they once called home, my work begins from that same sense of longing, as well as my sorrow for my friends, relatives, and family who remain there, without the freedom they deserve.

Therefore, rather than promoting or asserting any specific ideology, my work expresses the desire for reunification, in order to guarantee the fundamental rights, freedoms, and dignity that every human should have.

I hope that viewers approach my work not through the lens of political or ideological interpretation, but with simple human empathy and sincerity.

At the same time, I often worry that my work will be interpreted solely through a stereotypical perspective. While I will continue to tell stories related to North Korea, I hope that my identity as a defector does not overshadow the artistic value of my work. The title of “refugee artist” can, at times, bring greater visibility, but also risks confining me to a single framework. That is why I wish to be seen not as a “refugee” or “defector” artist, but simply as Koi, the artist.

Although my early works, inevitably, began from the context of North Korea, I now want to share the world of Koi, the artist, in a new world shaped by new environments and experiences. Right now, I feel ready to swim forward once again, to the next stage of my growth.

In your current exhibition, you have a lot of text, from Shin’s A Letter to Koi’s Parents and The Time of Koi, inscribed in the pieces, inside the shoes typically worn in North Korea, (and also available in English translation, in the show in Incheon). I’m curious about the writing side of your practice, which also comes into play in your visual work. Your letters read almost like poetry, and they are displayed in short stanzas. Do you envision the texts as poem-letters? Do you each write separately, and do you share this work with each other as you work?

We each write our own texts in the works you mentioned. Koi’s writing is drawn directly from her lived experiences and memories, forming narratives. Shin’s writings capture her emotions and records of Koi’s life from her point of view as a mentor and fellow artist working alongside her.

The shoes in “The Time of Koi” bear letters from Shin to Koi’s parents in the North, of her diligent and hardworking days in the South, to one day deliver to her family and friends when they meet again. To have one’s life documented and transformed into art is a profound gift. Koi’s life already shines radiantly, and she has someone who values and honors her sometimes rocky life by her side.

I’m struck by the subtlety and strength of your message, which pervades your work. Your work makes space for both the difficulty of the journeys made by defectors and their families and the shared hopes and a profound vision for individual freedom and collective reunification. What is next for your partnership?

We would like to express our sincere gratitude for the positive reception and encouragement we’ve received towards our exhibition and work.

The reason we’ve been able to collaborate consistently over the years is that we complement one another’s strengths. Shin brings exceptional curatorial expertise and insight, and Koi adds the drive, sensitivity, and precision that bring each project to completion. There are works we could have never brought to realization without one another. Our collaboration finds strength in our relationship, rooted in mutual trust, support, and lifting one another up. We hope that the messages we share through our works will reach beyond this country and serve as a bridge for harmony for people everywhere, across all borders.

We will keep steadily moving forward. Our recent exhibition, 19+16ing 展 There and Here, is another beginning, another departure in our continued journey together.