Cuneiform serves as a touchstone for Iranian sculptor Behdad Lahooti. In the series Chahanchah, the artist carves or paints cuneiform script onto everyday objects: a portable gas can, a watering can, a water jug, a pickle jar, a dustpan. The juxtaposition of an ancient script onto household items alludes to power structures shadowing the most ordinary of activities. A dustpan bears part of an inscription found on glazed bricks in Persepolis:

Xerxes the King says: By the favor of Ahuramazda, this Colonnade of All Lands, I built. Much other good (construction) was built within this (city) Persepolis, which I built and which my father built. Whatever good construction is seen, all that by the favor of Ahuramazda we built.

In some cases, Lahooti’s cuneiform-riddling of a common object destroys its use value. The water bottle, pocked with ancient script, no longer holds water; the gas container, commemorated, now leaks.

While Chahanchah plays with the rhetoric of ancient inscriptions, the series A Cliché for Mass Media addresses political rhetoric in contemporary Iran. In this series, Iranian urinals are covered in the artist’s retorts to the bombast of Iranian politicians.

The following interview with Behdad Lahooti was facilitated by curator Nazila Noebashari, the owner of Aaran Gallery in Tehran. The following answers were written by Noebashari in consultation with the artist.

—Eva Heisler

In Chahanchah, Behdad is carving cuneiform script onto everyday objects. Are these actual cuneiform letters, or are they only meant to echo the look of cuneiform?

Yes, they are actual cuneiform scripts, and are famous texts of the kings of the Achaemenid Empire, which emerged around 550 B.C.E. Behdad uses bas-reliefs and inscriptions on stone walls and different objects found in excavations of historical sites.

“Shahanshah” was the title of Persian kings, meaning “the King of Kings.” The artist’s title is a play on words, because “Chahanchah” in a way means “abyss,” so the title is referencing the history of Iran and how everything has disintegrated.

Cuneiform script was one of the earliest known forms of written expression, emerging in Mesopotamia around 3000 B.C.E. The script was widely used on commemorative stelae and carved reliefs to record the achievements of the rulers, or simply to convey the messages of the kings to future generations.

Behdad’s use of cuneiform is simply an echo of the past in the present: the grand wording of these bas-reliefs contrasts with the reality on the ground.

I find it interesting that Behdad, as a sculptor, is “carving” an ancient language. Any thoughts on the relationship between sculpture and language?

Yes, indeed, this is the part that has been fascinating for Behdad. The art of carving bas-reliefs in Iran goes back millennia, and carving on objects made for temples or kings or grand families is an old tradition. It is exciting to walk in the footsteps of great artists whose names do not appear in history books.

As a contemporary artist, Behdad finds it exciting to bring the past into the present. The series Chahanchah includes objects in bronze, a lasting material, as well as objects in plastic. This is an effort to show that, in the end, it is the artwork and the idea that count, not the material.

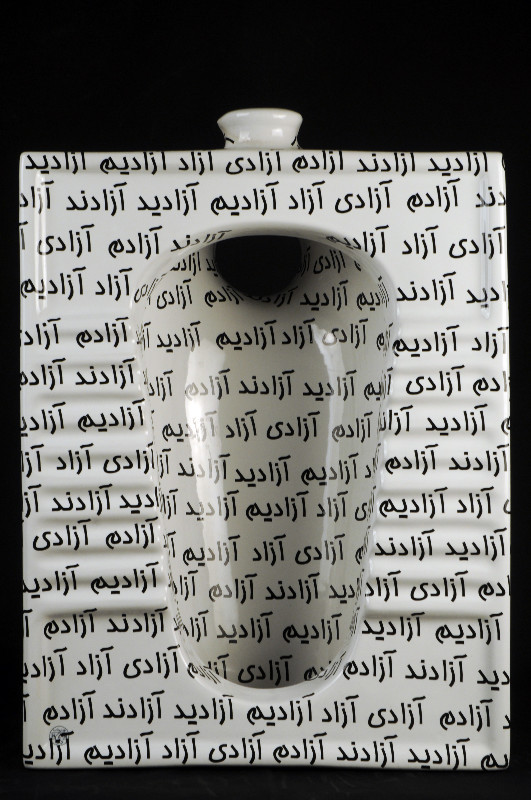

In A Cliché for Mass Media, toilets are printed with bold script that looks like newspaper headlines or signage. For our non-Farsi readers, can you explain the choice of texts to print on the urinal? They are political slogans, right? Can you translate a few of the phrases for our non-Farsi readers?

These were a series that Behdad created in reaction to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the infamous President of Iran from 2005 to 2013. Whenever he said something totally false or partly true, which he often did to manipulate the situation, Behdad answered back.

The first urinal was in reaction to a high jump in the price of tomatoes, an indicator of how the economy was crashing. Ahmadinejad said that, in his neighborhood, tomatoes were still very cheap. In answer to another question, Ahmadinejad said Iran’s youth could enjoy bank loans for marriage. None of these statements were true.

In another statement, Ahmadinejad said, “Our people are free.” And Behdad replied by saying: “I am free, you are free, they are free . . . ”

In a Western art context, the urinal often evokes Duchamp’s presentation of a urinal as sculpture in 1917. Since Behdad is a sculptor, is he referencing Duchamp? (Forgive me if this is a hopelessly Eurocentric question.)

Yes, of course Behdad is doing that, but he was also belittling and humiliating the president and other “seats of power,” which is often done in Iranian contemporary art.