I was first drawn to Tsouhlarakis’s sculptures for their distinctive visuality and later to her text-based work, all of which possesses a stripped-down honesty that enables her to approach the cultural misapprehension of Native existence with humor instead of confrontation. Having followed Tsouhlarakis’s career for long, I was overjoyed when she agreed to this conversation. It illuminated many of my concerns regarding form, language, and the politics of representation, and I am grateful for the opportunity to share it with Asymptote’s readers.

In your artist bio, you identify as “Navajo + Creek + Greek.” Could you talk a little bit about how these identifications shaped your career as a multimedia artist? How did each of these identities find expression in your early work in sculpture, which was one of the first media you worked with?

I’m Navajo Creek and Greek. Growing up, knowing that I was Native and Greek was a huge part of my identity. This sense of identity was instilled in me, especially by my dad, that I was fully Greek but at the same time also fully Native. It wasn’t an either/or situation: I was fully both cultures. That really informed who I am because, even though growing up I didn’t know much about Greek culture and my Greek ancestry—all of my Greek family lives on the island of Crete, none of them speak English, and it wasn’t until I was in my twenties that I learned to speak Greek fluently and started visiting them regularly—my Greek side has always been alongside my Navajo identity, which I was more in touch with. I grew up in the States and within Native communities; I was very entrenched in Native ceremonies, went through my puberty ceremony when I was a teenager, and had a traditional Navajo wedding. And so, I’ve always known that I’m both of these identities even though they’ve shown up in my work differently, because my Native identity has been much more at the forefront and center for most of my life.

My identity inspired me so much as I was becoming an artist. My dad is a silversmith and makes jewelry, so I was always exposed to a lot of Native art, different art markets, and exhibitions where Native artists were showing. In college, I knew that sculpture would be my main mode of creating and working. It spoke to me the most clearly, and I’ve explored my Greek identity through it. In my recent exhibitions, a body of work that started with Indigenous Absurdities, there are a lot of white body casts, and the compositions are more influenced by classical Greek sculpture.

You continued to experiment with the sculptural form in your 2021 exhibition To Bind or To Burn. Made from IKEA furniture remnants and found materials such as wood and natural fibers, the sculptures you created feel striking, theatrical, and uncompromising. They evoke an element of the unexpected, either in visuality or the choice of the materials combined. You mentioned that this project was inspired by Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes, which is an exercise in form, structure, and the possibility of world-building. How does To Bind or To Burn receive and challenge LeWitt’s ideas of form as building blocks of representation? How does it approach, through form, Native experiences?

When I first began making the work for To Bind or to Burn, one thing I was thinking about was the term of decolonization, especially in the context of the late 2010s and early 2020s. It was a term, and still is a term, that people use in a lot of different conversations, such as decolonizing an institution, decolonizing a community, and so on. When I started brainstorming for this project, I wondered what the term would look like in terms of art. If I’m this Indigenous person coming in and trying to decolonize something, what would I be decolonizing in terms of art? And because Sol LeWitt is often considered the grandfather of minimalist art—when we think about him, we think about his cubes—I was invested in his Incomplete Open Cube series. I was thinking particularly about form, which is the structure that needs to be decolonized. That’s what I started working with.

In terms of material, in place of the big metal pieces that LeWitt used, I used Ikea remnants, which I found to be very similar to LeWitt’s choice in their minimalist, clean, and white aesthetics. In terms of the concept of decolonization, when we put a de- in front of something, what we’re referring to most of the time is the deconstruction of something, and that’s not what I was interested in. I wanted to focus on the evolution of something into a more indigenized form. That’s when I realized that I was most drawn to indigenization and not decolonization. Using LeWitt’s exercise as the form of Western art that needed to be indigenized, I created a kind of recipe, if you will, of materials that would suit my objective. I used aspen, metal, and found objects, and bound them together with pieces of leather or even a metal C-clamp. So, essentially, the whole project and its process were born from my inquiry into indigenization.

0/It Started Like This, 2020. Digital Video. 5:00 minutes (Video Still).

In To Bind or To Burn, the action of binding holds a lot of weight. It is rooted in Navajo culture as a lesson in self-control, respect, and balance within the worlds of human and nature. Children are bound to cradleboards and, as they grow older, tie their hair up in a bun with a strand of woolen thread. But To Bind or To Burn focalizes the potential constraint and violence of binding. I’m curious to know how you conceived of the sculptures in this project, and more specifically, the process by which you revise the definition of binding in Navajo life.When I began reflecting on the action of indigenization, I thought a lot about what it is that makes a person indigenous; in other words, what makes them different from something or somebody else. And so I started thinking about my own tribe, specifically Lake Navajo, what defines Navajo life, and what separates us from other tribes. I did a deep dive into all the traditions that we have and my family experiences growing up.

When I was a baby, I was usually in a cradleboard. As soon as I could sit up and my hair started to grow out, my grandma would brush my hair and put it up in ponytails, and when it got long enough, either braid it or put it up in our traditional bun or something like that. Binding, I realized, is an action that was consistently done throughout my whole life. It’s something that I’ve instilled in my children as well. I don’t think it’s something that people talk about—I’ve never heard other Navajos say, Hey, we bind things. But to me, it is a sort of ritualistic practice in our culture. I consider it the form or the action of indigenization, and I wanted to try to utilize it within my sculptures. Deciphering the instances that are consistent throughout my lifetime is an important part of my work.

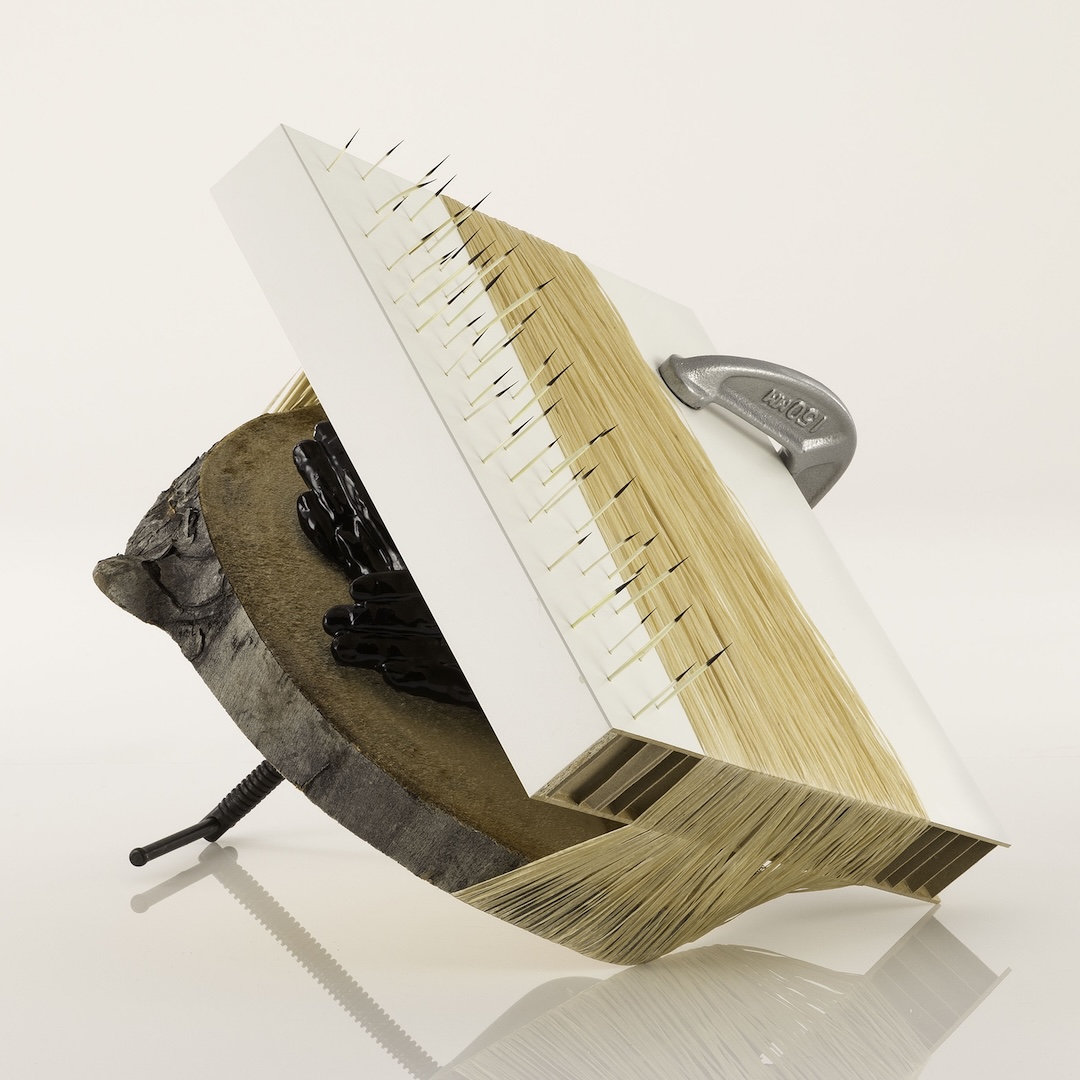

1/It Keeps Going, 2020. Found wood, IKEA remnants, porcupine quills, sinew, galvanized C-clamp, resin, plaster. 16” x 17” x 19”.

1/The Way It Was Told, 2020. Found wood, IKEA remnants, porcupine quills, sinew, flex sealant, plaster. 23” x 10” x 10”.

Your 2016 exhibition She Made for Her features three large-scale sculptures, with the voices of Native American women in a multi-channel sound installation describing the objects as they see them. The creation and transference of meaning here, then, is threefold. You create the sculptures from your vision, before passing them onto the Native American women whose voices we hear on the sound installation; the women then offer their distinctive readings of the sculptures; lastly, when the viewers enter the exhibition space, they are confronted simultaneously with their own reactions to the objects, their speculations as to your authorial intention, and the commentary of the Native American women. As an artist, what do you make of the complexities of interpretation, especially in cases where cultural expectations and assumptions prevail?I’ve been thinking about the expectations or assumptions that viewers have when they enter an art space the entire time I was making objects, and even before that. I realized at a young age that people expected Native artists to make Native-looking things, and the idea that Native artists couldn’t just make whatever they wanted really upset me. As I got older, when I was in college and started learning about art histories within different cultures, I saw artists in the trajectories of Latin American art, Black American art, or Asian American art working in installation and video and performance, also with certain expectations upon them. But when I first encountered their work, I thought they were stretching the understanding of what their culture meant or could mean, and wondered where that was for Native artists. It was the nineties, and whatever the Native artists did to challenge preconceptions wasn’t necessarily in the mainstream art world, so I really wanted to help redress the situation.

I wanted to make work that wasn’t instantly thought of as Native work, that wasn’t identifiable as Native work. I wanted it to be grounded in Native ideas, philosophies, and teachings, but I wanted it to expand the definitions. And She Made for Her dealt a lot with storytelling, interpretation, and how things can change from one person to another. Essentially, it is asking, what is the truth? What is the right truth? What are kids going to learn in schools next year? For me, all of these things are intertwined, and as an artist these are things that I want to explore and challenge.

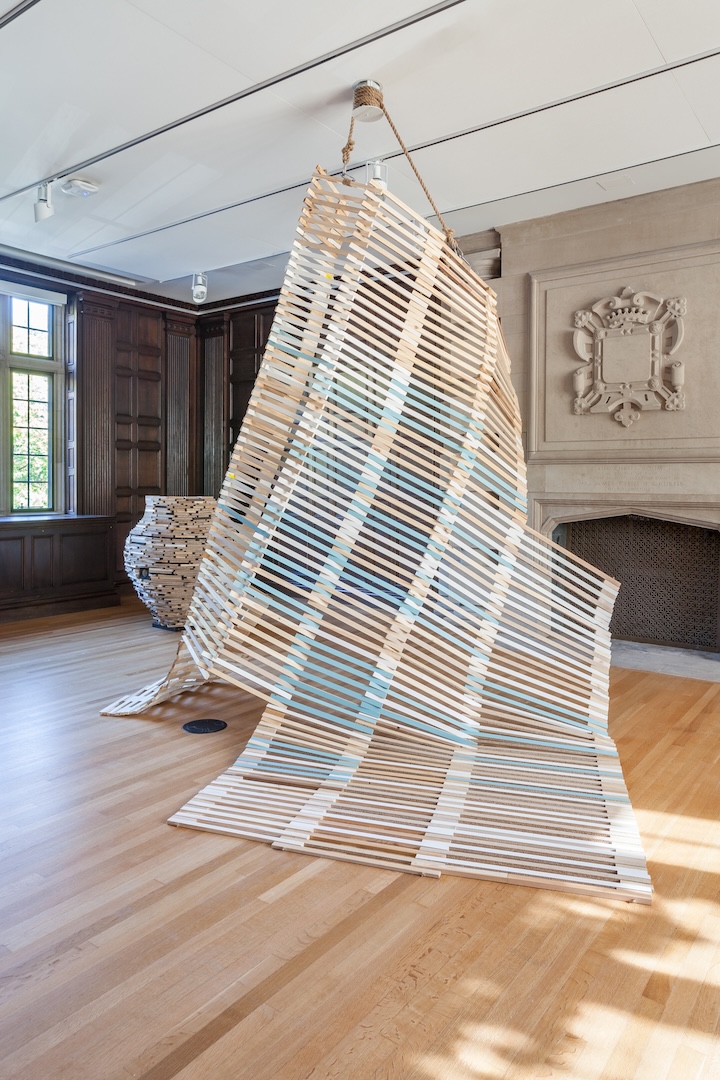

She Made for Her, 2016. IKEA remnants, screws, and found IKEA twine. Dimensions variable.

She Made for Her, 2016. IKEA remnants, screws, and found IKEA twine. Dimensions variable.

She Made for Her, 2016. IKEA remnants, screws, and found IKEA twine. Dimensions variable.

Your work seems to take a different turn with Indigenous Absurdities (2023) and The Native Guide Project: Columbus (2023), primarily text-based projects foregrounding Indigenous humor. What inspired this departure? How do you characterize the role that language plays in your practice?When I was younger, I hated writing, and I think it was because I didn’t learn how to be a writer. I didn’t have teachers who pushed us to believe that we could be writers, and so I never thought I was a good writer, and I always felt like it was just something that I was bad at. It wasn’t until college that I realized how important it was to get ideas across succinctly and clearly.

The first time that I created a text piece was in graduate school. The idea of putting text into an art piece happened because storytelling has always been a part of my lived experience, and it was something that I wanted to translate into the art space. As the years went on, I began to use text more in different ways, and in 2012 I started attempting larger installations with it. It was in the background of the sculptural things that I was making.

But things really came to a head in 2019, with the first version of The Native Guide Project that I did. I feel like that’s when I truly understood why I wanted to use text—how to use it in a direct way, and how to integrate it visually into my work in a much stronger way. That’s when I realized that, in terms of communicating ideas, there was a clarity to using text that I couldn’t otherwise achieve with any image I could create or build. Since then, I’ve done many iterations across the country. One of the major ones was The Native Guide Project: Columbus, where I began incorporating the histories of the local area.

The element of humor has always been present in my work, and part of the intention of The Native Guide Project was also to test out this underlying tone of sarcasm. The project really brought out the humor, which might not be as obvious in my previous work, because I realized that I could create text that was double-edged in terms of being really nice but also sarcastic. Since then, I’ve explored humor in different iterations.

I loved doing The Native Guide Project. I started working on physical billboards, social media, digital billboards, and banners on the exterior of buildings. In 2023, when I was preparing for Indigenous Absurdities at MCA Denver, I wanted to create indoor pieces that could link my sculptural work to my text work. I was trying to figure out how to bring the text indoors and not have to put it on a huge billboard, and came up with the idea of paper collages on big wood panels that are about four feet by six feet. In Indigenous Absurdities, there are six of those, and they are made up of large printout paper collages with memes and images that speak to the text. The titles of the pieces, to me, are just as important as the pieces themselves. That is the linkage between the text and the sculptural work: I want to make sure that titles are very straightforward, because they inform so much of the work that people are seeing, and that’s something I hadn’t ever felt strongly about before.

SHE THINKS SHE’S TOO GOOD, 2023. Keg, books, foam, wood, tobacco lids, mesh, metal, resin, adhesive, chattering teeth, leather, plaster, IKEA remnants, wood, paint, plastic, found objects. 8.5’ x 5’ x 5’.

SHE MUST BE A MATRIARCH, 2023. Fiberglass horse, paint, adhesive, resin, plaster, plastic, wood, foam, metal, IKEA remnants, leather, prophylactics, found objects. 8’ x 15’ x 4’.

Both Indigenous Absurdities and The Native Guide Project: Columbus deploy boldface one-liners directed at a potential interlocutor, usually sarcastic in their direct, biting concision. They remind me of Lauren Berlant’s comment that politics is always emotional, often described in a rhetoric that intensifies fantasy—which, I recognize, is not directly applicable to your work, since your projects actively expose fantasies and stereotypes. But they do engage with the audience emotionally in that they point them to the faults of their understanding of Native American existence. How do you think affect shapes the way the audience receives and responds to politically charged representations of Indigenous identity?I think that it can either draw people in or push people out. That’s why I use humor and sarcasm and what I hope is wit, because it softens the playing field a little bit, and it makes my work seem more approachable. Somebody might read part of the text and giggle for a little bit before realizing, Wait! Should I be giggling? This happens continuously as I go from project to project. It helps open the door to more engagement with the viewer.

Right. So, how do you negotiate the tension between levity and gravity in your projects, and what do you think distinguishes humor from other possible modes of inquiry?

When I think about how to approach ideas, especially within Native communities, around women and strength, or even around relationships and similar themes, I find that humor is a powerful tool. Humor doesn’t just make things more engaging—it lets you see them from a different perspective. Laughter, or even just a giggle, softens the entry into difficult conversations. I think that’s important because I want to be engaged too, and I want to laugh. I’m not always interested in artwork that only makes me angry, mad, or sad. Nobody wants to constantly be told that they’re responsible for the downfall of the world. So how do we talk about serious issues without turning people off? I don’t think I’m belittling the issues—I’m making them more accessible and more interesting for others, but also for myself. It becomes a challenge: how do I engage with these topics in a way that allows them to be layered—serious, humorous, thought-provoking—all at once?

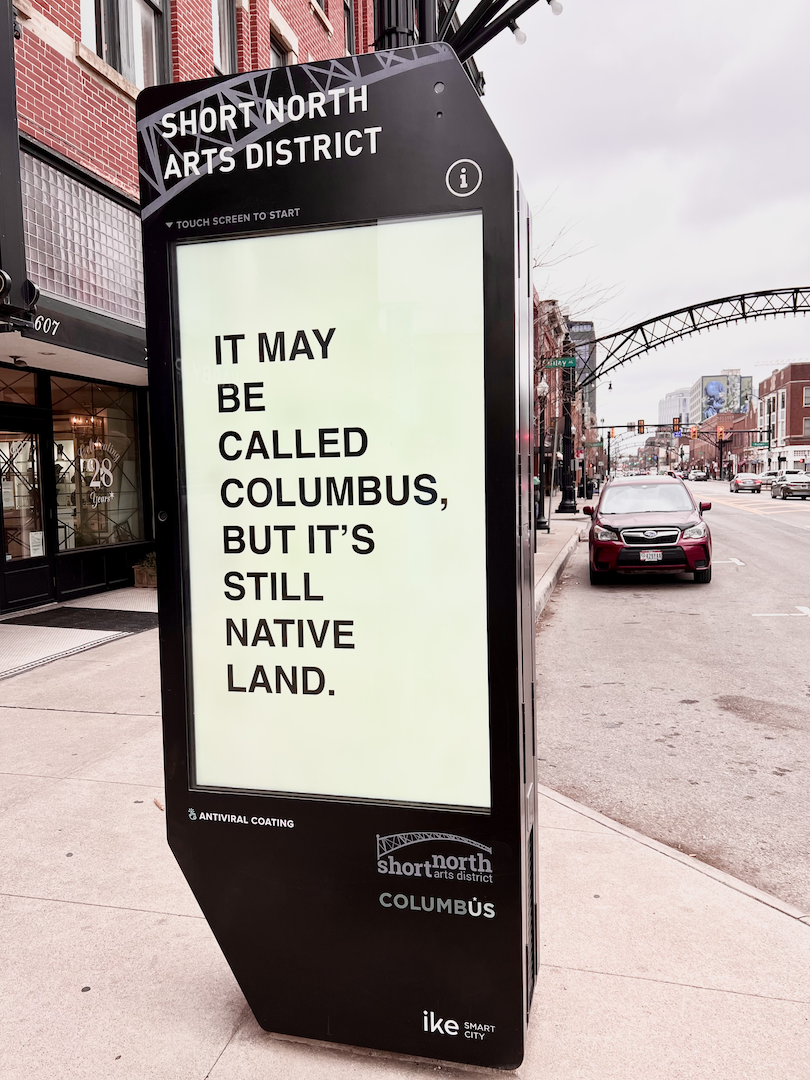

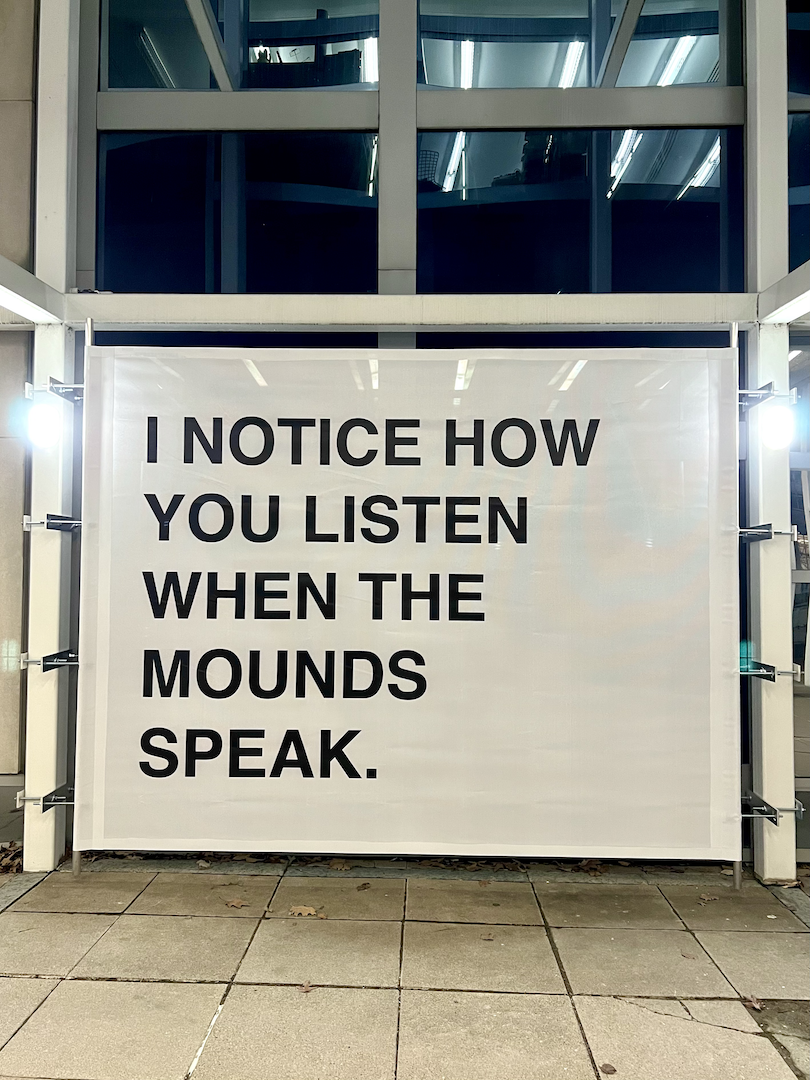

The Native Guide Project: Columbus, 2023. Phototex, vinyl banners, IKE monitors, digital billboard. Dimensions variable.

The Native Guide Project: Columbus, 2023. Phototex, vinyl banners, IKE monitors, digital billboard. Dimensions variable.

The Native Guide Project: Columbus, 2023. Phototex, vinyl banners, IKE monitors, digital billboard. Dimensions variable.

Throughout your career, you have drawn from the lives of your family and friends while collaborating closely with Native American communities across the U.S. How has this ongoing engagement with community and collective creation shaped your understanding of authorship, and in what ways do you see collaboration as central to both your practice and the preservation of Indigenous knowledge systems?I love engaging with people. I love engaging with communities and learning about different people’s experiences. I learned fairly early on that when I come up with an idea and I want to execute it, it tends to be pretty narrow. There’s usually a clear line from the idea to what I want to make about it. And I knew that as a communal artist, that’s not how it works.

While I listen to communities and learn a lot from different people and try to incorporate all of these lived experiences into my work, I’m not trying to speak from the “I” perspective, because I don’t want to assume the narrative of another Native person or another tribal community, especially if it’s not my own. I always want to make it clear what I am in terms of my tribe, where I come from, and my relationship with where I’m working. Last summer, I worked on an installation at a botanical garden in Maine, and I was using oyster shells and granite to discuss relationships with land. While I was inspired by these ancient mounds that were in the area, I always strove to emphasize—when I was talking or writing about the piece of land art—that it was something I created with full awareness that I’m not from this place. I don’t want to take ownership of any narrative that deals directly with ideas of place in relation to another tribe or tribal community. Right now, we like to talk about the universality of a certain experience, but I think it’s just as important to focus on the diversity of perspectives in communities, too.