Laila Mourad’s voice rings out in the café next door: “Swear on my troubles, which never trouble you / and on my / youth, which eluded the two of us. . . .” She runs her fingers over her face, feeling for wrinkles. She knows she will start to wither soon, or so her mother, her relatives, and the neighborhood women say. The mirror tells her the same: she’s confronted with the gray that has appeared around her forehead and that she hurries to hide with henna paste—just one of many forms of denial. All this time she has not heard a word from him nor a credible report that he reached the other shore. She grasps at straws—she actually believed the guy who came back and told her he saw him there. Some nights she curses his name, but she invents excuses for him during the day. She refuses to believe he might have drowned on the way.

Fridays, before the rest of the house is awake, Gamila gets up and shuts her bedroom door to keep anyone from hearing what she’s up to inside. She takes the cardboard boxes out from under the bed and lays them in a circle. She sits at the center and opens them one by one. She uses a clean cloth to wipe away the dust; she arranges it all in front of her: a china set with little colored flowers, metal pots, a set of utensils, coffee cups with paintings of Romeo and Juliet, glass cups with gold rims. As she peers at them, the tears flow. She packs them carefully into the boxes again and puts them back in storage. She can’t stand that the sheets and towels are going yellow in the suitcases above the wardrobe, and she worries about moths; she presses mothballs inside. She looks at the shining gold band on her finger and at their picture together—she in a pale pink dress with layers of tulle, he with the chain to put around her neck, each with a shy smile—and begs him to come back. When she hears the tread of her mother’s footsteps on the way to the bathroom or to wake up the household, she climbs in bed again and pretends to sleep. She hears her mother’s voice from behind the door: “Hey, rise and shine everybody, it’s noon!”

The Seaman

His mother and his sister didn’t know much about his work; like most men who worked at sea, he left and came back with fish or cash. But they were proud that he had added “Captain” to his name as a key part of his inheritance from his father, who left everything to his son when he started aging. Mustafa took the title with the boat. Women whispered behind their backs: “What’s he all puffed up about? It’s just one boat . . . imagine if he had more?! Rest his father’s soul!” They joked about how his father used to shake in his boots when the weather turned and the waves crashed on the ships, which sounded to him like strikes in the war he had escaped from with only half his mind. It was an open secret that their good-natured husbands were in the habit of indulging the old fool: “They only called him ‘Captain’ to be nice!”

It seemed that Mustafa—with his intensity and his cruel features—wanted everyone to forget his father, who had been such an embarrassment to him when he was younger. He crossed the river to the island facing their small city to escape his peers’ teasing, and there, he worked in the fishing boats, learning the trade far from any mention of his father’s past, which he thought was shameful. He trained himself until he knew the sea like he knew his way home. He learned things that had never even crossed his father’s mind: that the sea had more to offer than fishing—there was another trade that paid more and journeys longer than the one from his city to the neighboring island. He navigated deeper depths and perils more fearsome than the high winds. He learned to track the moon and wait for darkness to fall, to use fake names. That the first stages required kindness to attract customers, but he’d have to be harsh after that. To be on his guard always. But to reach this level of skill took wounds and even more mistakes, the biggest of which he thought he had buried at the bottom of the sea with all the drowned, leaving his face that much crueler.

Troubled History

It must be something in my DNA. I don’t mean to stir up their patriotism by teaching this country’s history. Why would I when I, myself, have given up on all that? The nation, patriotism, national belonging . . . that heavy legacy of inflated feeling. Delusions made to subjugate us, the miserable. Even more miserable are those whose parents force them to sit in front of us from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. as we turn them into little clones of ourselves, with our flaws and obsolete ideas.

They drop out of class like flies. I keep a notepad in my pocket to record the names, the dates they stopped coming, and a street map sketch marking each house from which I lost a student. My thoughts get muddled and fill my sleep with heavy nightmares that mix sometimes with reality until I can’t tell the difference.

I dream that a tsunami strikes the coast. I stand in the schoolyard, screaming, Everyone, south! The sea is coming! It’s coming! Throngs of students flood out the school gates, going north—toward the sea—indifferent to my cries about their impending death. Who could say that those in the South were safe anyway? Time passes quickly, and the sea is a ferocious, unrelenting foe: we do not know where we will die.

A historian visits me in a dream. He opens a book and—like a Quran reader performing the ten styles of recitation—starts repeating, “That great surge annihilated a third of Egypt’s population, and the land went fallow for lack of men to sow it.” His voice gets louder, angrier, and more intense with each reading, mixing with the voice of the newspaper-seller passing under my balcony. I bolt out of bed and glance around quickly to get my bearings. I come back to myself when I realize that I’m in my room and there’s no turbaned man reading from a yellowed book. I recognize the seller’s voice as it gets clearer. I let the hot air out of my lungs and go to the bathroom to dunk my head under a stream of water, washing away the rest of the nightmare.

At morning assembly, I catch myself counting the students in each class. I rush through the hallways and into the classrooms to gather the attendance logs then storm into the principal’s office without knocking. He jumps up, thinking that some disaster has stricken the school. When I demand to call the parents of the absent students immediately, he tells me I’m deranged. He’s fuming with rage that a history teacher has trampled all over his office for nothing. We raise our voices. I call him complicit, and he calls me insane: “Anyone who doesn’t want to learn can stay away! You think you’re going to save the world?” He threatens to file a complaint against me if I don’t give up this superstitious nonsense. Colleagues intervene to break it up.

I leave the office, retreating to a corner of the teacher’s lounge. I rest my head on the table and close my eyes; the nightmares come back. There are no students at all this time. Rather, there’s an imbecilic band playing a funereal rendition of the national anthem while the teachers salute the flag with a gravitas unsuited to the absurd scene. In the classrooms, teachers stand like robots, giving lessons to wooden chairs and tables despite attendance logs that bear witness that no one comes. I walk out the iron gate of the school, which they lock to prevent the nonexistent students from escaping. In vain, I comb the streets, the fishing boats on the shore, the houses. I realize abruptly that it isn’t just the school—the students have left the city altogether.

No men under forty are left. The uniformed girls and young women coming back from school look to the sea with grief. I look in the mirror to find that my hair has grayed and my face muscles have slackened, as if aging is the only thing keeping me from disappearing with the rest. The city itself is in the throes of death between young women’s tears and the indifference of the world outside, distracted by its wars from the future of its inhabitants.

I wake up to the bell for the next class. I walk in and ask the students to open their books to the Fraser expedition. This particular lesson alerts the students to their intimate link with the geography that has befallen their city’s shores, the history that has touched its streets. Their attention reassures me, helps me regain my balance. I talk and talk until I’m straying from the curriculum and they’re asking to know more.

Troubled History

I had nowhere to hide when Captain Mustafa asked me with a look what I had told her. I know that was what he was thinking, and even though I hadn’t told her, I was ashamed, as if the past were coming back to life. He himself only knew what he’d seen when he’d shown up like divine intervention to save a man and his life jacket swimming around before dawn. He didn’t ask if I’d been on the boat that sunk; that was obvious. What else would I have been doing on the open sea at that hour? But he didn’t know what had happened before that—nothing about Idris, whose head I can still feel on my shoulder. It’s true that I’m not looking for him like Umm Batta’s looking for Imad, but I see his face on every corpse that comes out of the sea. I know this is crazy. Umm Batta might know it too, deep down, but she’s a mother; she had every right to lose it mourning her son. Idris has no one to mourn him. I might be the only one who even knows he drowned. He fell through the cracks of this world so allegedly concerned about human rights. The prophet Idris left Babylon asking God to reward him and his tribe with another one, and God blessed him with the Nile Valley. But at that point the river barely offered anything to its own people anymore, so how could someone else expect anything different?

We sat opposite each other in the corridor in front of the stash house bathroom, our faces so close that I could feel the breath going in and out of his broad nose. I had covered mine with a shawl to filter out the mixed smells of the toilets, the rubber shoes, the people, their breath, and the food scraps. The shoes especially stunk up the whole place. He seemed unbothered. He looked into my face as if he had something to say but was holding back. His furious eyes made him look like he was about to stand up, indifferent to the bodies he’d trample in the process, and clock me smack in the nose to make it stop its kvetching. Maybe he thought I looked like a privileged kid who had never tasted hardship, and that pissed him off. He shot me another mocking look when I turned down the piece of stale bread stuffed with cold beans passed around by the armed men hired to enforce order and carry out the terms of the deal. We were a herd of sheep under their command. I hate weapons and I hate coarse men; I also hate getting stepped on.

In the first hours his look was sometimes sardonic and sometimes angry. I was trying to think of something else to break the cycle. I thought of the house we sat in—what its walls might have held before dreams of people fleeing from hell. A whole family had lived there before giving it up to the smugglers. I didn’t imagine this family had sold the house; they’d just rented it with some conditions, the most important of which was that nobody find out who was sleeping there.

At sunrise or a little before, the owner would come from where he actually slept to make it look to the neighbors like he was just coming out of this house by the palm to pray the dawn prayer with them in the nearby mosque or to go to work. His wife pretended that she was sitting with her kids under the palm, getting up every few minutes to go into the house and come out again as if she had been doing some chores. And so on. She divided her afternoons between sitting under the tree and sitting between the migrants—captives in the walls of her home, a steady stream of changing faces. The family would wait until dark fall to evade the neighbor’s attention as they slipped away to their real home. The owner was unaware that his neighbors had all struck the same deal. They’d leave their houses in the evening and come back before sunrise to act out scenes of quotidian life in front of one another—imaginary lives. Imagination, though, offered some comfort to our minds at tough moments, keeping us from losing them like we did our dignity, our spirits, and the luster in our eyes. I played make-believe to escape Idris’s looks, the bean sandwich, my fear of the man with the gun, and my broken heart.

In the evening, which came very early since hope for the following day was all we had, everyone fell asleep and we—Idris and I—still sat opposite each other. I hugged my bag; he had nothing but his body and the clothes on his back. He started drifting off to sleep for a few moments, and it seemed like exhaustion got the better of him: his head fell on his shoulder and his mouth opened like a dark cave, the tears flowing from his eyes and glistening on his brown skin. He didn’t seem to feel them. He started trembling and raised his voice as if calling out to someone. He jerked awake, opening his eyes to find me just as he had left me before drifting off. He lowered his head, no longer looking me in the eye. I avoided his gaze again.

I gave him my water bottle. He hesitated, then reached out and took it, then raised it and emptied it into his throat. We didn’t speak or sleep until sunrise. I learned his name that day when I overheard others saying it: “Idris Wad as-Silk.” He was one of the Eritrean migrants. Most in this house were Eritrean and Sudanese; the Egyptians were the minority. I pressed my face into my knees and hugged it between my arms to hide from everyone. The few times I raised my head, I looked for him; he had changed his place, no longer paying attention to me. When the signal to move came in the evening, I didn’t notice whether he was there or not. I was just happy and relieved that we were getting out of this prison.

If the signal hadn’t come and things had stayed as bad as they were the first night, I might have held my breath for good. I didn’t want to go back, and I hadn’t left Alexandria to be debased like this somewhere else. I forced patience, telling myself that this was the last time I’d be humiliated in this place; as soon as I set foot in a new country, I’d turn the page, write a new history, and forget the past. No one on the other side had witnessed anything of that past, with its stains of disgrace that made me cringe. We left in the bed of a truck that usually transported sand—everyone from the house was in one truck, or so I gathered from the voices around me. Slim brown bodies trampling right over life in their quest to find it. I say this though I myself have trampled my own dignity on my way to finding it. It’s not their fault, and it’s not mine either. All homelands are burning embers: if we hold on to them we get burned. What better than water to put out the flame.

There was little airflow, and the temperature was rising. The tarp covering the truck bed was heavy. Only wide eyes lit the scene. Someone pulled out a small blade and sliced into the tarp, forming a hole to help us breathe. The truck stopped and stood still for a long time, our hearts still with it. They started whispering that the police had caught onto us and were going to lift the tarp off within a few seconds, sending us to an undesired fate. I closed my eyes and my fist hard, clenching my jaw to stop myself from screaming.

Was Idris the one with the blade? Could I borrow it to slit my veins and be done with all this? The truck started moving again, and our hope was restored. I was now grateful to have the tarp hiding us, and I wished I had a needle and thread to mend the slit the blade had made. We kept moving across the smooth sands under the rule of those armed men. They saw themselves as gods because they could extinguish the life from a body with one squeeze. They were like everyone who carries guns: even though we had paid them for the job, they were euphoric when they hit their carefully selected targets—an eye that dared a defiant look, a leg that crossed the distance to challenge their authority, or a heart that dreamed of life. All warranted punishment, torment. They tormented like gods and strutted around with vulgar arrogance, hiding behind the weapons hanging from their waist. I despised myself even more as I realized that I was avoiding looking at them.

I held back tears, imagining that if I cried, the fires burning in my heart and mind might die down. All that separated us from the water now was a hill of sand; when we crossed it, the first stage of the trip would be over. My feet sunk deep into the soft sand and I fell on my knees, losing the momentum of the climb; a hand seeming to come out of nowhere pulled me forward. In the moonlight, I saw Idris’ arm pulling me to the hilltop, its length gashed with scars. We threw ourselves into the water.

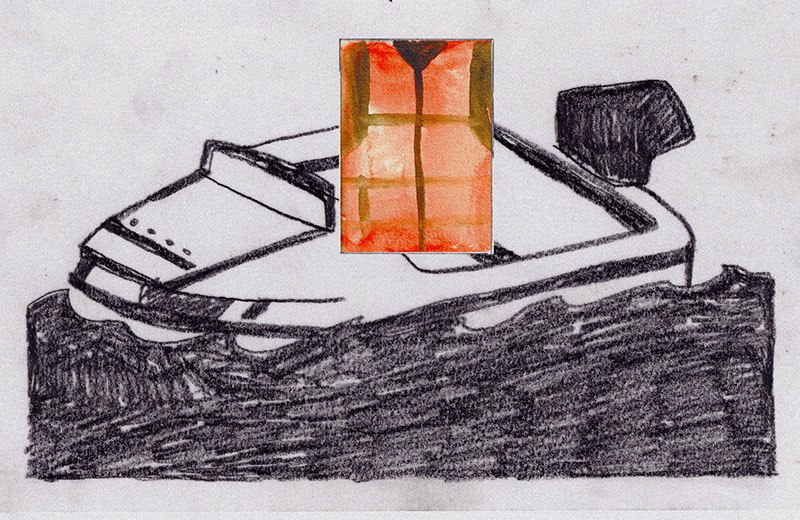

The boat was a few meters away. I was wearing an orange life jacket, and Idris was in a sky-blue, light t-shirt, flapping his arms in the water. He kept moving forward a little before the waves pushed him back to the shore. I didn’t notice, busy as I was with swimming along, trying to get away from the land with all the determination I had left. The boat was nearly empty; it seemed like we were among the first to arrive.

The sea was familiar. It was as if it hadn’t forgotten that teenager who always arrived at Gleem Rock ahead of his peers, passing through the cave at Bir Massoud, holding his breath and defying all his mother’s warnings. I felt safe in the sea—it was the same sea that crowned my city and knew me well. I had been reluctant to buy the life jacket, but my defeat in the face of everything I thought I knew well made the decision for me; why would I be so sure of myself against the sea? I felt I should be leaning on it for help with all my troubles. We needed something to keep us afloat on land, not at sea—something to carry us through our misery and save us from our memories. This is what I was thinking as I arrived at the boat ahead of the crowd.

I don’t know when exactly Idris’s fever started. We were sitting in the belly of the second boat as it continued zig-zagging east and west. It had not started heading north yet, and everyone was seasick. The bucket being passed around didn’t stop anyone from vomiting on the person next to him.

Idris’s head was on my shoulder this time. He’d die before he saw the other side, he said. Fear and fever and seasickness, despair creeping into his heart. Was he delirious when he talked about Emanuela, his lover, who’d been killed by the soldiers, as he said? He had left her slight body on the ground without looking at it to say goodbye and without knowing whether they buried it. Did they leave it to the stray animals? He’d left her and kept going, and now her memory haunted him in his dreams and delirium. It was her name he called when he panicked in his sleep before, and she was the reason for his tears.

“Adam Wad as-Silk” and I took turns holding a wet rag to Idris’s head. They weren’t relatives, Adam explained. “Wad as-Silk” wasn’t a family name; it wasn’t a real name at all but a nickname—“the Wire Boy”—added to the first name of migrants who had crossed from Egypt into Israel through the razor wire at the border. He rolled up his sleeves, and I saw the same scars on his arm as Idris’s. Idris hated Israel. Emanuela died at her gates after crossing deserts and villages from Eritrea to Sudan and Egypt. Killed by a bullet fired by a soldier guarding the border with the enemy, and Idris entered Israel grieving and alone. He had thought of it as the promised land—as they themselves claimed. He spent the twenty months following his arrival in a detention center in the Negev Desert. At that point they were all given the choice of incarceration or “voluntary” deportation; policy interests prevented him from becoming a refugee. It was the first time I heard that one of them wanted that title. What would happen when we arrived on land? Would I, too, become a refugee? People’s problems are nothing when compared with those of others; it really makes you hate yourself even more. The world is a ravenous, insatiable beast swallowing us up in its jaws, and none of us—no one on the back of that boat—wanted anything more than to live free of persecution. Who pulls the strings in this world?

The boat kept coming and going along a single line, each time taking onboard a new crowd of people from one of the smaller boats. We took Idris to the upper floor to get some air. The passengers were shouting at the crew, and the crew was threatening to turn back; no orders had been issued yet. Chaos erupted on the deck. We were supposed to come up on the final boat at the maritime border. Had the crew abandoned us when water started filling the belly of the boat? All I know is that I put the life jacket on Idris before we were in the sea, and I swam a long way dragging him behind me, with him begging me to leave him behind. He told me that God was punishing him because of what had happened to Emanuela. I dragged him by the belt of the life jacket and used my other arm to swim. I didn’t know in which direction I was swimming; I just kept moving forward. When I felt completely alone in the darkness, I looked behind me for some company, but there was no trace of him. I hadn’t realized that Idris had taken things into his own hands: he’d unbuckled the lifejacket and gone, leaving to me the lifejacket and life itself.

Continental Drift

“Have you ever heard of a poet who started a poem by praising death? If I were one of the writers of the Muallaqat, I would’ve done that.”

I was not sure how we reached this point. Did he tell me I shouldn’t have come with Gamila? Had I asked him about all he was hiding from me? Did we make tea together in the kitchen, barren but for a teapot and a few cups? Maybe he told me about Idris. Our backs were glued to the ground as we looked up at a drawing of a map on the ceiling. The Mediterranean took up most of the space, as if it were the center of the universe. He said it would take a thousand years for the sea to dry up. He went quiet for a minute. He said he was thinking about how many corpses we would find at the bottom if we could live until it did dry up. I realized then that he had started to ramble. I did too, telling him it would take a thousand years for us to find Umm Batta’s son in the belly of the sea to put her ailing heart to rest.

He said that the continents were once all a supercontinent called Pangaea—a theory. The African landmass had started drifting counterclockwise while the Eurasian one moved opposite, shaping this rift that the ocean would fill to drown the wretched in its depths. He rattled off dry facts about evaporation rates and climate change while my thoughts stayed on the massive landmass and its opposing turns: were the two of us turning in the same direction? Had Alaa been turning opposite? Were Hamid and Alaa turning the same way? Was I really searching for my father’s grave, or was I in his city to try to reunite Pangaea? My mother and I had been a single unit moving together until she had left me, and I had clung tightly to my father until he had followed her. Then Alaa, then Hamid, today. Maybe I was the one turning in the wrong direction, losing everyone. An uncrossable sea had formed around me and drowned them. I was alone.

I imagined a rope hanging from the ceiling. I imagined Hamid wrapping it around his waist and stretching his body the length of the sea, moving like an acrobat, his feet in Port Said and his palms in Cyprus. Then he’d turn the rope until his feet landed in Alexandria and his palms in Turkey. Then again until his feet were in Sallum and his palms in Crete. He was still going on about the Mediterranean. My head started to spin. I realized that Hamid and Mustafa never stopped talking about the sea. The sea, center of the cosmos and the ceiling above our heads. Only people like me who lived far from the coast were ignorant of its gravity; the capital is central for us—us with our endless contempt for other cities. We pride ourselves on being the origin of everything: science, civilization, urbanization, even language; we’re never sick of our stupid jokes about other cities’ accents, ignoring the evidence in our parents’ faces that our city is woven from varied threads, distinct in their colors and textures, plucked from the remote corners of this country that birth and bring up their young before sacrificing them to the capital. I thought of my father. Cairo had been the city of his dreams. Then he was gone, leaving me to search in the abyss of the Delta for his grave despite Sara’s advice that prayers would reach him from anywhere, so there was no reason to look.

What if Sara knew about Umm Batta? Would she tell her to read the opening chapter of the Quran for her son on the shore? What would she tell Gamila if she knew her story? Sara did not really understand things. Each of us is on their own journey searching for something. The three of us—Gamila, and Umm Batta, and I—were searching for death: the one certain truth with which we could face the world. Hamid was interested in the same thing, but in a different way. He stopped talking suddenly, looking sullen.

“What’s the point of all this if it’ll all end up in the sea?” he said in a voice that made him sound like he’d settled something.

I left his house in the cover of darkness. He went ahead to scout things out, and I followed when he gave the signal. Though he didn’t realize it, a new piece of his tragedy had been transferred to me—as if I were the one crouched in a boat crossing the sea. As if I were drowning again, as if Idris’ head were on my shoulder. I too felt like drawing maps all over the walls. When I opened my phone, Gamila’s messages had tipped over into expletives.