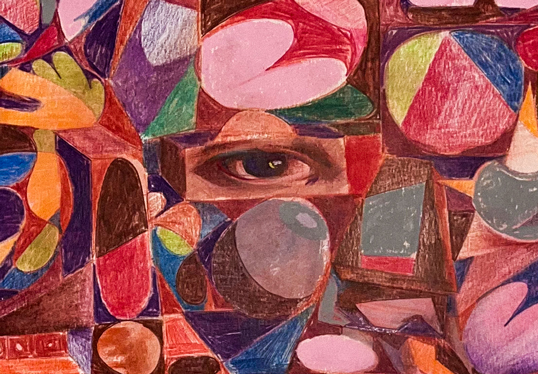

We live in an era of click-consciousness where attention, splintered into micro-moments, has become the chief currency and wound of our age. Its deficit is called a new global epidemic. In this noise, I see another image, bequeathed to me from childhood in a small Russian town: a boy, his forehead pressed to a frozen windowpane, watching snowflakes—whole worlds—melt on the glass. In that moment, the world lost its sharp outlines but gained a bottomless depth. I was not searching for anything; I was preparing to receive everything. It was my first, unknowing communion with the mystery of attention not as capture but as grateful dissolution.

Yet within the Russian tradition there exists another, starker image: life as a narrow neck, a metaphor drawn from Boris Pasternak’s vivid imagery. This definition pierces deeper than any scientific model. The neck is a place of existential constriction, where the flow of being, the roar of history, and the cry of one’s own soul are compressed to a limit. One may squeeze through this narrowness—or get stuck and suffocate. The entire paradox of the Russian understanding of attention is contained here: it is simultaneously a site of utmost suffering and supreme insight. That very “narrow neck” is the focal point, the locus where scattered experience becomes destiny, and the world’s noise becomes meaning.

Why, in Russia, has this phenomenon acquired such an agonizing bond with pain, conscience, and memory? Perhaps the answer lies in its very geography and history—a long exercise in survival on the edge. Vast expanses demand not external markers but an internal compass; a harsh nature teaches one to notice the finest crack in the ice; social cataclysms force one to read between the lines, to hear the subtext in an official slogan. Here, it is not the swiftest who survive but the most attentive—those whose gaze can perceive the concealed: a tremor in the voice, a shadow of suffering in the eyes, meaning in a silence.

This is not Eastern contemplation seeking dissolution into nirvana, nor is it the Western pragmatic focus aimed at efficient results. The Russian gaze is focused on the impractical: on the soul, on pain, on eternity. Its goal is not mastery over an object but communion with it, even if that communion burns.

In this essay, I trace how two great rivers of Russian thought—the scientific and the artistic–explore this “narrow neck.” We begin with the Russian physiology of the soul, where the rebellious “inhibition” of Ivan Sechenov, wresting free will from the matter of the brain, transforms into the spiritualized dominanta of Aleksei Ukhtomsky, and then collides with trauma in the “romantic science” of Alexander Luria, studying the disintegration of attention as the disintegration of personality. From here, we move to literature as the crucible of suffering attention, where the “narrow neck” becomes a red-hot needle’s eye for the soul in Dostoevsky, a surgical instrument in Tolstoy, and a keen ear attuned to the music of silence in Chekhov.

We will then see how this agonizing gift turns toward the world: how in Bunin and Nabokov attention becomes a lens for transfiguring reality, while in Mandelstam and Platonov it becomes an attempt to palpate the very substance of existence. Finally, we will enter the purgatory of the twentieth century, where the hammer of history tests attention to the point of rupture. We will see it narrow to a slit of survival in Shalamov, reassemble the self from shards in Solzhenitsyn, operate as a protocol of catastrophe in Ginzburg, and execute a metaphysical escape from time in Brodsky.

In the end, this journey from reflex to meaning, from suffering to witness, from disintegration to memory will crystallize a particular gift of attention. In an era we timidly call the “age of distraction,” the Russian tradition offers not a life hack but an askesis. It teaches us not to economize attention but to spend it lavishly on what is essential, even if the essential is another’s suffering, a silence, or an inconspicuous detail in which an entire universe is hidden. By exploring this “narrow neck of being,” we may find not only a key to Russian culture but also a salvational prescription for a consciousness drowning in a stream of meaningless information: the ability to learn once more to see—intently, painfully, gratefully.

Science: The Russian Physiology of the Soul—From Reflex to Meaning

The Russian science of attention was born not in the quiet of studies but on a battlefield for the human soul. Its starting point was not an academic dispute but a loud public scandal. When Ivan Mikhailovich Sechenov published his work Reflexes of the Brain in 1863, it was an act not only scientific but civil—a bomb thrown at the foundation of official ideology. The book was immediately banned, and the author was put on trial “for spreading materialism and corrupting morals.” The authorities instinctively sensed the danger: Sechenov had encroached upon the last bastion of metaphysics—free human will—by proposing to explain it through the workings of nervous tissue.

But wherein lay this heresy? Sechenov revolutionized the field by discovering in the brain the mechanism of central inhibition. Before him, the reflex was seen as a direct, inevitable arc: stimulus—reaction. Man appeared a puppet of external influences. Sechenov showed that in the higher nerve centers, excitation could be delayed, redirected, suppressed . . . Here was the first rudimentary physiological circuit of attention. Sechenovian “inhibition” is precisely that initial “narrow neck” through which the chaotic stream of external stimuli first squeezes to become a selective, meaningful response. This was the birth of freedom from matter: man is not a slave to reflex but its judge. The pause between stimulus and reaction that Sechenov discovered—that is the gap where everything human resides: thought, conscience, choice.

If Sechenov hammered open this neck, Alexei Alexeevich Ukhtomsky took up the task of studying its shape and purpose. His genius concept of the dominanta became the cornerstone of the Russian science of attention. The dominanta is not merely a focus of excitation in the cerebral cortex. It is a principle of meaning formation that organizes all behavior and perception around a primary, urgent need. Ukhtomsky saw in the dominanta not biological determinism but the foundation of ethics.

For him, the dominanta was plastic and cultivatable. The highest, specifically human dominanta, he proclaimed, was “the dominant on the face of the other.” “The other,” wrote Ukhtomsky, “is the one who dominates in you by their attention to you.” Here, a scientific term turns into spiritual revelation. His thought finds one of its purest expressions in the idea that to love is to experience proof of the other’s irreducible existence—a physiologically precise formula of mercy. Ukhtomsky’s dominanta is an icon rendered in scientific language: another kind of “narrow neck,” but one directed not at food or danger but at the face of another through which, as through a window, reality itself is revealed.

Paradoxically, within the same laboratory milieu where Ukhtomsky’s spiritualized physiology matured worked his intellectual antipode—Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. If Ukhtomsky sought in neural activity the basis for meaning and encounter, Pavlov described with mathematical rigor the mechanism of conditioning. His famous dogs demonstrated a perfect, freedom-less picture of attention-as-reaction. A bell (conditioned stimulus) inexorably led to salivation (conditioned reflex). The “Pavlovian dog” became a symbol of man as a complex but predictable machine, whose attention is wholly manageable by external reinforcements. This debate—Ukhtomsky vs. Pavlov—is a debate about the very essence of attention: is there room in it for meaning and transcendence, or is it merely a refined tool of adaptation? The Russian tradition decisively chose the former.

Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky shifted this debate from physiology to culture. For him, attention was a higher mental function not given at birth but formed in social interaction. A child first follows the pointing finger of the mother (“attention shared between two”), and only later is this gesture internalized, becoming their own internal tool for managing gaze. Attention, for Vygotsky, is initially external, social, dialogical. His famous “zone of proximal development” is precisely the space where an adult, directing the child’s attention, cultivates new abilities within them. Thus, our “narrow neck” is not of a fixed, innate diameter—it can be widened or narrowed with the help of cultural tools: words, gestures, symbols.

The tragic culmination of this line of thought came with the work of Alexander Romanovich Luria, in the middle of the tumultuous twentieth century. His neuropsychology was born of necessity: he became a chronicler of the disintegration of attention. Studying war veterans with traumatic brain injuries, Luria saw how damage to the frontal lobes destroyed “dynamic afferentation”—that very plastic system of regulation described by his predecessors. His patients could not switch from one task to another; their attention either became stuck on one thing or slid helplessly, holding onto nothing. Luria called his method “romantic science” because each case was for him not a set of symptoms but a drama of personality that had lost its integrity. His famous patient Zasetsky (from the book The Man with a Shattered World ) with damage to the occipital lobes could not assemble the world from fragments: he saw patches, details, but was powerless to synthesize them into a coherent picture. Here, attention appeared as the fragile scaffold upon which our “I” is built. Destroy it—and both the world and the personality crumble into meaningless shards.

Thus, Russian scientific thought, beginning with Sechenov’s “inhibition” as an act of freedom, arrived at Luria’s analysis of the disintegration of attention as the disintegration of being itself. It traveled from reflex to meaning (Ukhtomsky), from the individual to dialogue (Vygotsky), from wholeness to trauma (Luria). It never regarded attention as a simple “spotlight of consciousness” (William James) or a “filter” (Donald Broadbent). For this tradition, attention was always a cultural and ethical phenomenon—that very “narrow neck” whose shape determines what from the noisy stream of reality will reach our soul and become part of our fate. It was this spiritualized, suffering optics of science that prepared the ground for how the phenomenon of attention would be endured and sung in great Russian literature.

Literature: Attention as Suffering and Co-suffering. Through the Needle’s Eye of the Soul

While Russian science sought the mechanisms of attention in the convolutions of the brain, literature immersed it in the very thick of suffering human flesh. Here attention ceases to be a function and becomes a fate—a burdensome gift that does not illuminate but scorches, and it is only through this burning focal point that true reality is revealed. The scientific “narrow neck” of Sechenov and Ukhtomsky transforms in literature into a red-hot needle’s eye, through which the hero must thread the camel of his own soul.

Fyodor Dostoevsky: The Hell of Hyper-Attention

In Dostoevsky, attention is first and foremost a disease, a fever of consciousness. His heroes are not contemplators of the world but its agonizing witnesses, whose inner gaze is turned not outward but inward into their own abyss. The narrator of Notes from Underground is the direct antithesis of the Ukhtomskian ideal. His dominant is not “on the face of the other,” but on his own humiliation, on corrosive self-reflection. He is attentive to himself with a pathological, almost surgical precision, turning every impulse inside out. This is attention as self-torment, trapping a person in the vicious circle of the “underground.” Here, the neck of consciousness is narrowed to a limit and directed inward, creating an infernal, vacuum-like pressure.

Yet Dostoevsky offers another model—the ecstatic, sacrificial attention of Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. Myshkin does not see as others do. His gaze is that of a “holy fool” (yurodivy), which pierces right through social masks to the concealed pain of the other. He notices a grimace of suffering on Nastasya Filippovna’s face where others see only beauty and provocative behavior; he reads the despair in Rogozhin’s eyes. His attention is a form of immediate, defenseless co-participation. He does not analyze another’s suffering—he absorbs it as his own wound. And herein lie both his strength and his doom. The needle’s eye of his attention is opened so wide to the world that all its pain bursts through, shattering his fragile psyche. In Dostoevsky, attention is always on the verge of breakdown: it either seals a person within themselves or exposes them to complete defenselessness before the anguish of existence.

Leo Tolstoy: Defamiliarization as a Moral Operation

Tolstoy approaches attention as a spiritual practice, a surgical instrument for cutting to the truth. His famous technique of defamiliarization (ostranenie)—later theorized by Viktor Shklovsky–is an intentional “making strange” of the habitual, meant to force both the hero and the reader to see a thing as if for the first time. Here, attention is not a natural flow but an artificially induced shock.

In Tolstoy, the greatest epiphanies are born at the breaking point of habitual attention. The wounded Prince Andrei (War and Peace) on the battlefield of Austerlitz sees the sky—“the lofty, just, kindly sky.” In that instant, his attention is violently torn from the vanity of glory and war and fixed upon the eternal. This “narrow neck” is a sudden breakthrough from time into infinity. The agony of Ivan Ilyich (The Death of Ivan Ilyich) is a methodical, inexorable switching of the dominant. The dying body, its pain and fear, become the sole object of attention, displacing all the trumpery of his official, “proper” life. And it is then, in this hell of concentration on decay, that he notices the face of his servant Gerasim–simple, compassionate, alive. This detail, this “trifle” that had never before drawn his attention, becomes a revelation for him. It is that very “dominant on the face of the other” which breaks through egoism and horror, granting forgiveness and insight at the very edge of death.

Anton Chekhov: The Poetics of the Unspoken and the Ethics of the Periphery

Chekhov accomplished a quiet revolution by shifting the focus of attention from the center of the drama to its periphery, from direct statement to pause, from action to state. His attention is not a spotlight illuminating the climax but a diffuse light in which everything becomes important, especially what remains “off-screen,” outside direct sight.

In The Lady with the Dog, love is born not from passionate declarations but from a shared, silent contemplation of the sea, from an unfinished phrase, from a casually exchanged glance. Chekhov’s characters cannot speak of what matters most, but the author’s attention—and, consequently, the reader’s—is riveted to these ruptures, to this overlooked realm. The sound of a snapping string in The Cherry Orchard is a quintessential Chekhovian detail. It has no direct plot significance but becomes a powerful object of collective attention for both the characters and the readers. In it resides all the unspoken longing for a vanishing world, the foreboding of a rupture, a metaphysical crack in being. Chekhov teaches us to attend to silence and emptiness. His “narrow neck” is not a point of bright light but rather a fine sense of hearing, catching the echo of truth in the humdrum noise, in an awkward pause, in an absurd detail behind which lies a whole universe of yearning or hope.

Nikolai Leskov: Attention as Folk Mastery

At a folk-miraculous pole lies the attention of Nikolai Leskov’s heroes. His “enraptured wanderer” Ivan Flyagin (The Enchanted Wanderer) or the legendary left-handed craftsman (Levsha from The Steel Flea), who shod a steel flea, possess a particular kind of attention—not reflective, but purposefully concentrated on skill. The gaze of Levsha is that of a microscopist and jeweler, allowing no room for abstract thoughts, only for the ingot, the tool, and the miracle to be performed. This is a folk, guild-like analogue of the gift of attention—not the agonizing gift of conscience characteristic of the intelligentsia, but the onerous gift of talent and duty. His “narrow neck” is the watchmaker’s loupe, through which a microcosm is visible, and within this microcosm the fate of national pride is decided. Here, attention becomes a form of righteous labor and almost pagan miracle-working.

Thus, nineteenth-century Russian literature created a whole typology of suffering attention. From the infernal self-analysis of the “underground man” to the sacrificial openness of Myshkin; from Tolstoy’s surgical defamiliarization to Chekhov’s keen listening to silence; and further to the concentrated wonder of Leskov’s masters. Common to all is the understanding that to truly see is painful. True attention demands sacrifice: of comfort, of illusions, sometimes of sanity. It is a tool not of cognition but of insight, and what it most often reveals is not light but an abyss—external or internal. It was this literary experience that prepared the ground for the twentieth century, where attention would be tested to the point of rupture by historical catastrophe, and the “narrow neck” would shrink to the size of a camp ration or a morsel of siege bread.

Attention to the World: From Contemplation to Transfiguration

Following the agonizing focus on the suffering soul, Russian thought makes a visible, yet deceptive, turn towards the world. This, however, is not an escape but a different form of deep immersion. If in the nineteenth century attention was a needle’s eye for the soul, then in the prose and poetry of the turn of the century and the early Soviet era, it becomes a lens—an optical instrument through which the world is not merely observed but dissected, transfigured, and recreated anew. Here, the “narrow neck” does not constrict but focuses, gathering the scattered light of existence into a blinding ray of meaning.

Ivan Bunin: The Gratitude of the Gaze

In Bunin, attention is almost a religious act of gratitude. His descriptions of nature, scents, and light in Antonov Apples or Dark Avenues are an attempt to arrest and preserve the very act of perception itself. Instead of analyzing or reflecting, he captures reality with a photographic, yet spiritualized, precision. The smell of honey and autumn decay, a ray of sun on worn velvet, the chill of morning—all become objects of reverent, slowed attention. Bunin’s attention is contemplation in its pure form, where the observer’s “I” temporarily dissolves, yielding to the unconditional realm of the visible and tangible. His “neck” is the aperture of a camera, generously open to admit all the light of a moment, transforming it into an eternal snapshot of memory. This is a Zen-like equanimity, yet tinged with a Russian, aching nostalgia for a lost paradise.

Vladimir Nabokov vs. Ivan Bunin: Mastery vs. Communion

Alongside Bunin’s reverent detachment arises a different, dandyish, and virtuosic optics—that of Vladimir Nabokov (in his Russian period). For Nabokov, attention is a tool of aesthetic mastery over the world. His artist-hero (like Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev in The Gift) does not dissolve into the object of contemplation but catches it as an entomologist would a butterfly, to fix it in perfect verbal form. Attention here is a sharp, self-delighting intellectual game. A detail (a stain on a tablecloth, the curve of an eyelash, the play of light on a dragonfly’s wing) is valued not for its natural harmony with the world but as a unique, hard-won pattern that has been deciphered and described. If Bunin communes with the world, Nabokov collects it. His “narrow neck” is the collector’s magnifying glass, enlarging the particular to the scale of a universe, yet always maintaining a distance of cold, admiring mastery between the object and the gaze.

Osip Mandelstam: Touching with the Gaze

The poetry of Osip Mandelstam introduces a new quality to the theme of attention—tactility.

Lines such as “I’ve been freezing my hands in my sleeves” offer a formula for the fusion of visual and physical sensation. Attention for Mandelstam is not passive; it presses against the world, palpates it like a blind man. “A sighted finger”—his precise self-characterization. In The Noise of Time, he writes not of events but of the material of memories: the smell of leather gloves, the sound of a tram, the texture of wallpaper. His attention snatches not ideas but the flesh of an epoch, its tangible, almost edible grain. The neck of his perception is not only an eye but also skin. Through this neck, the world enters the poet not as an image but as a physiological experience, which later, under the pressure of rhythm, crystallizes into verse. Herein lies its tragic power: when the material world he had so palpably attended to began to crumble, his poetry became the cry of flesh deprived of its foundation.

Andrei Platonov: Listening to the Substance of Existence

The apotheosis—and simultaneous dead end—of this lineage is Andrei Platonov. His characters attend not to objects or beauty but to being itself, to the “substance of existence.” They “listen” to silence, “look” at a thought, try to catch the attention of a star or a suffering bush. Attention for Platonov is pushed to ontological absurdity—it attempts to grasp what is by definition ungraspable: the meaning of history, the secret of life, the pain of the universe. The hero of The Foundation Pit, Voshchev, collects in a sack “substances of the forgotten meaningful essence”—a parodic and terrifying image of attention devoid of an object, attention to emptiness itself.

Platonovian attention is an unbearably widened, and therefore tormenting, neck. His characters are like a Ukhtomskian subject deprived of a concrete dominant, trying to make all of existence its dominant. They listen for guidance in the noise of the cosmos, hoping to hear within it an instruction on how to live. And they hear only the wind, the screech of iron, and their own exhausting anguish. This is attention that does not transfigure the world but lays bare its metaphysical wound, its “orphanhood.” From Platonov’s experience, the direct path leads to the twentieth century, where attention will narrow to a single, animal task—to survive.

Marina Tsvetaeva: The Fury of Absorption

At the opposite pole lies the furious, absorbing attention of Marina Tsvetaeva. Her poetic “I” does not contemplate or palpate—it pounces upon the object of attention to draw it into itself completely. For her, all love is a gaze. Her attention is an act of immediate appropriation and fusion, almost violent: “I absorb you, like a sponge—wholly!” Here, the neck is not a lens or a needle’s eye but a funnel, sucking in the world with such force that the boundary between inner and outer is erased. This is attention as conflagration, attention as hunger. It does not fix or transfigure—it devours reality to convert it into the furious energy of verse.

Thus, in this chapter on attention to the world, we witness not a retreat from tragedy but its sublimation into aesthetic and metaphysical tension. From Bunin’s grateful acceptance through Nabokov’s virtuoso mastery and Mandelstam’s tactile listening—to the ontological impasse of Platonov and Tsvetaeva’s furious absorption. The Russian gaze, tuned to the world, proves no less tragic than the gaze tuned to the soul. It collides with the muteness of matter, the impossibility of fully embodying meaning and, therefore, of a final merger. The “narrow neck” as a lens gathers light, but beyond the focal point of this gathered ray, what often appears is not a clarified truth but a scorching void or an all-consuming fire. This strained optical instrument, ready to snap, will be mercilessly tested and reforged in the crucible of history, which will be the subject of the next, most terrible act of our drama.

The Twentieth Century: Shattered Attention and Memory

The twentieth century approached Russian attention with the hammer of history and the red-hot chisel of ideology. What in science was the theory of the dominanta, and in literature a metaphor of the red-hot needle’s eye, here became a literal, physical experience of survival. The trauma of the epoch did not merely fracture attention—it tested its very limits, like the neck of a carafe tested by the pressure of expanding ice. It turned out it could not only be narrowed but shattered, transformed from an organ of meaning into a fissure through which nothingness seeps. And it is precisely within this fissure, on the very edge of dissolution, that attention acquires its final, sacred function: to become the organ of memory and an act of resistance.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Attention as Askesis and Self-Reassembly

In One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, attention becomes a form of askesis, a spiritual discipline under conditions designed for the disintegration of personality. Shukhov (the eponymous Ivan Denisovich) does not reflect or daydream but instead scrupulously documents reality. His consciousness operates as a precise, economical mechanism: to freeze at the right moment, to hide a hacksaw blade, to procure an extra ration, to avoid the punishment cell. This is attention narrowed to the bounds of an operational field of survival. Yet within this narrowness lies not animality but the highest humanity. By noticing how a snowflake settles on a mitten, how a brick is correctly laid, how the winter sun shines, Shukhov is not merely surviving; he is assembling around these details the scaffold of his “I,” which the camp seeks to annihilate. His “narrow neck” consciously filters out the poison of despair and absurdity, allowing through only that which can be mastered, used, or simply acknowledged as a sign of continuing being. This is attention-as-construction, brick by brick erecting a fortress of dignity within infernal walls.

Varlam Shalamov: The Disintegration of Attention as the Disintegration of Personality

If in Solzhenitsyn the neck narrows but holds its shape, in Shalamov it cracks and tears. His Kolyma Tales are a clinical record of the disintegration of attention, described with the protocol-like ruthlessness of a physiologist (which Shalamov, the son of a priest, was by training). The attention of a starving, frozen man is not merely narrowed—it is riveted to a single point, beyond which lies nothing. “The dying man’s attention was completely switched off from the future,” he states. The hero sees a breadcrumb, a nail mark on a wall, a button on a dead man’s coat—and this consumes his entire mental resource. Thoughts do not flow but convulse, like those of Luria’s patients with frontal lobe lesions.

Here, a nightmare dissociation occurs: attention separates from personality. A man still registers a detail (the brainstem works, the Sechenovian reflex) but is no longer capable of weaving it into any meaningful narrative about himself (the functions described by Ukhtomsky and Vygotsky fail). Shalamov shows the terminal station of the path that began with Luria: when the “functional organ” of attention is destroyed, the personality disintegrates, leaving only a biological shell registering pain. Here, the neck is no longer a tool but a wound through which life drains away.

Lydia Ginzburg: The Protocol of Catastrophe

A unique hybrid case is presented by Lydia Ginzburg. In her siege diaries Notes from the Siege of Leningrad, she applies a method akin to the scientific one to the apocalypse: cold, analytical attention to the mechanisms of decline and survival. She observes herself and others as a researcher, identifying not types of heroes but “types of behavior.” How does speech, gesture, gait change under the influence of hunger? How does memory work? How does attention, deprived of its usual objects (books, conversation, plans), switch to the micro-rhythms of the body and daily life?

Her attention is an instrument of testimony, deliberately detached from direct suffering so that this suffering can be accurately described and preserved for history. This is the “narrow neck” of the intellect, which she, against all odds, manages to keep open, turning it into a slit for an objective lens. Through it, she sees not a private tragedy but an anthropological catastrophe in its pure, almost laboratory form. Ginzburg combines the position of the scientist (Luria observing disintegration) and the saint-chronicler, for whom attention is a duty to a vanishing reality.

Joseph Brodsky: Attention as an Escape from Time

Against this backdrop, the poetry of Joseph Brodsky comes across as an attempt at escape from the vise of historical time through an even narrower neck—the neck of metaphor. If the attention of Shalamov and Ginzburg is chained to the “here and now” of catastrophe, Brodsky’s attention is a gaze “from here—into eternity” or, more precisely, a gaze upon the momentary from the vantage point of eternity.

In “Still Life” or “The Hawk’s Cry in Autumn,” the object of intense, almost microscopic attention becomes a negligible detail: dust on a table, a crack in the ceiling, the trajectory of a bird’s flight. But through the prism of language, rhythm, and cultural memory, this detail transmutes. Dust becomes a metaphor for time, the hawk’s cry—an arrow piercing the void of being. Brodsky pushes to its limit Chekhov’s poetics of the “trifle” and Bunin’s fixation of the moment, but he fills them with existential and metaphysical weight. His attention is an alchemical retort in which the lead of everyday experience (including the experience of historical trauma) is transmuted into the gold of timeless meaning.

For Brodsky, attention is a form of gratitude to the world for the very fact of existence, despite everything. By concentrating on a detail, the poet rescues it from oblivion, and himself–from distraction. His “narrow neck” is the lens of a telescope, pointed not into the distance but into the depths of an instant, to discover within it an entire universe.

Thus, in the twentieth century, Russian attention passed through the purgatory of history, enduring every possible form of violence. It narrowed to a point of biological survival (Shalamov), was preserved as a bastion of dignity (Solzhenitsyn), functioned as an instrument of dispassionate testimony (Ginzburg), and finally sought salvation in a transcendent escape into language and form (Brodsky). The neck cracked but did not burst completely. In each of these fissures, as in a wound, memory continued to seep—the ultimate and chief product of attention, forged by an entire culture. It is this memory, concentrated and transfigured by the experience of the twentieth century, that constitutes the precious, burdensome gift that Russian thought can now oppose to the new, digital distraction.

Conclusion: The Neck as a Gift

The path we have traveled—from Sechenov’s “inhibition” to Brodsky’s metaphysics of the detail—is a history not of discovery but of anamnesis, of recollection. Russian thought, in its scientific and artistic incarnations, time and again reminds us of a single forgotten truth: attention is not a cognitive function but an existential stance. A mode of being in the world.

We began with the image of the “narrow neck”—Pasternak’s metaphor, which proved to be a prophetic cipher for the entire tradition. We have seen this neck change its nature: in Sechenov, it was a valve of freedom, wrested from a mechanistic world; in Ukhtomsky, a lens of meaning turned toward the face of the Other; in Dostoevsky, a red-hot needle’s eye through which the soul drags the camel of its conscience; in Tolstoy, a surgical incision laying bare the truth beneath the skin of habit; in Chekhov, an auditory canal catching a melody within silence.

The twentieth century pressed this neck with violent force into the flesh of time. In Shalamov it cracked, becoming a fissure through which nothingness seeps; in Solzhenitsyn, it was tempered into a bulwark of personal dignity; in Ginzburg, it became the objective lens of cold testimony; in Brodsky, an alchemical retort for transmuting the moment into eternity.

What unites these seemingly disparate forms is the understanding of attention as labor and sacrifice. The Western gaze often sees in attention a resource for optimization—a spotlight beam to be directed at a target. The Russian gaze feels it as a burden and a gift: a narrow place where the soul, compressed by the pressure of the world or history, either breaks or gives birth to a diamond of insight. It is not about efficiency but about dignity. Not about capture but about acceptance.

Today, as technology, having brilliantly realized Pavlovian principles, tightens its screws on a global system of conditioned reflexes—the infinite scroll, notifications, algorithms exploiting our dominanty—this Russian experience acquires the character not of academic knowledge but of existential necessity.

We stand before a choice: to allow our “narrow neck” to be narrowed to the dimensions of a smartphone screen, where the dominant will be a fleeting stimulus, or to consciously cultivate within ourselves a different one. To cultivate the dominant, as Ukhtomsky taught. To make it not reactive but selective. To direct it not toward what shouts loudest but toward what speaks most softly—toward the concealed, the unspoken, the other face.

A return to that childhood window is impossible. But one can transplant its principle inward. To turn one’s own consciousness into that very window—frosted, patterned with ice, on which whole worlds of snowflakes melt. Not for nostalgia’s sake but for the sake of a sober, difficult miracle. To see the world through such a window means to acknowledge: yes, the neck of being is narrow, it is tight and painful within it. Yet it is precisely through this narrowness, and not through the wide gates of distraction, that everything of weight and significance reaches us: the pain of another, transformed into compassion; the ephemerality of a moment, transformed into eternity; the noise of history, transformed into personal memory.

And then the “narrow neck” ceases to be a metaphor for limitation. It becomes a form of salvation. Salvation from distraction. From oblivion. From non-being in a stream of meaningless signals. To cultivate this Russian gift of attention in the twenty-first century is the ultimate, desperate, and beautiful act of resistance: to remain human in a world doing everything to make us forget what that means.