He wound up at a German university. He was alone, as were the others he’d arrived with, all of them alone. And of course the German women didn’t want to get involved with them, because what could a German woman do with an Asian man who, one fine day, ups and leaves her with a possible broken heart and even pregnant. The others at the dormitory, the German boys, could hardly manage all the girls, there seemed to be so many of them. Sometimes a boy would post a note on the door telling this Vietnamese student not to come back for an hour—such a humiliation, having to go out to the courtyard and then to a city park, often in the cold of winter, felt more intensely by someone from a warm country. I’ll die here and now, he thought, the frost will put an end to this life of humiliation. But the body prevailed. The body was not Vietnamese, it was a body first and foremost.

He’d trudge back an hour later and spend the whole night shivering under his blanket, dreaming about also being with somebody, maybe when he got back home. But for the time being there was no prospect of going home. He learned the language of his hosts so well it was as if he’d grown up in this German city, Dresden. Some of the local girls even began to forget that this fellow was Asian.

He was in his fourth year when that certain German girl came into his life. It was at a party in the dormitory. To him, she was very beautiful. With skin so white, she couldn’t have been otherwise. White is beautiful, what’s wrong with that? he thought, I’ve fallen in love. If it lasts only as long as I’m here, that’ll be good enough. I too will be in a position to post a note on the door—come back in two hours. One would have been enough, but he thought about writing two—as retaliation. Of course not even that was enough for the girl, who asked for assurances that they’d be together forever. He made promises of marriage, children, a middle-class life. He soon finished his studies and began working at a German firm as if he just wanted to gain experience, but he already knew he wouldn’t be returning to rebuild the ruined country.

Six years went by, and an opportunity arose for him to visit his homeland. The German woman’s tears were flowing as she accompanied him to the airport. When you get home, you won’t stay there, will you? No, he said, you can be sure I won’t. I can’t be sure you won’t, she said, because I can be sure about something that’s already happened, but not about something that hasn’t happened yet. But in this case you can be sure, he told her, though he knew as well as she did that she couldn’t.

He’d grown up in a small village in central Vietnam, where every foreign army had concentrated firepower, because that area formed the corridor through which northern troops passed and supplies were transported to rebels in the south. But all that bombardment came to nothing, because the invaders eventually had to cut and run, incapable as they were of dealing with those ragtag Vietnamese pouncing on the intruders from underground tunnels and unnavigable swamplands.

He arrived in the village, got off the bus and didn’t recognize where he’d once lived. The buildings weren’t the same as those he remembered, and many were gone. The only people he ran into were of the older generation. The mothers of his classmates were sitting in front of a shop. One of them cried out, is that you, Toán? It is, he said, and for a moment her face lit up, then turned dark. And where is my little boy, where is he? And where is my Khang? My Duong? My Khuong? The women looked at this survivor with a sense of pain mixed with anger, as if to say: this Toán, of course, survived, but what became of my little child?

This was how he made his way home to his parents. He decided that if he ever came back again, he’d arrive at night and wouldn’t leave his parents’ house. He did so several more times, though each homecoming only increased his alienation, the feeling that this was no longer his homeland. No one he’d grown up with was alive anymore, he couldn’t share memories with anyone. His past was obliterated—not changed, the way a middle-class life changes, indeed improves, with ever-more-advanced household gadgets. No, his past hadn’t changed, it had come to an end. It was no more.

That’s what he would tell his German wife when he got back. She was glad. They decided he didn’t need that past because, after all, he was building a new life, in a different country, in another language. And life in the German language came with even greater fulfillment when the two Germanies became one, and the family had access to the salaries and consumer goods that hitherto only denizens of the wealthy West had been entitled to.

They had two children, little girls. Toán became the chief engineer of a large German firm, though the other employees didn’t call him Toán, but Antoine. Thus his former name, which meant victory, became an affectedly French name. Could someone called Antoine truly be victorious in life? In his case, he did in fact appear to be a winner, despite being Asian, because he fit in perfectly. Over the phone, for example, no one would have guessed he wasn’t a native German. The mechanic he once called to come and repair the boiler almost turned around and left, since he assumed he’d spoken with a German man and must have mixed up the address.

They were about as content as an aging couple could be. Their daughters had moved away, and they thought about all the things the two of them could do together. For example, they could travel all over the world, even to Vietnam. They laughed about that and went on weaving the life-plans of an elderly couple.

That was how things stood when, one morning, the man complained of a splitting headache. Take something, the wife said and listed all the things a person can take, not to mention the various painkilling brews about which she knew seemingly everything. She was a believer in alternative healing, which began, as she’d explain, with medicinal herbs. But nothing helped, and she noticed that her husband, who normally expressed himself very logically, began saying strange things, for example, that he saw the children in the cupboard among the preserves, in a jar. He said this meant that they’d stay with him and wouldn’t move away, and the family would remain together and be complete. He made preserves of them.

She called the ambulance. At times like this the unthinkable can become reality in less than five minutes—in this case, a brain tumor and the urgent need for surgery.

That surgery, especially if the tumor is as deeply embedded in the brain as his was, can cause injury which, the doctor explained, can’t be attributed to medical error. The reason the patient couldn’t recover was part and parcel of the disease. He woke up after the operation, gazed at the German relatives around him, and listened to the alien language they were speaking, which, in the wake of the surgery, he no longer understood.

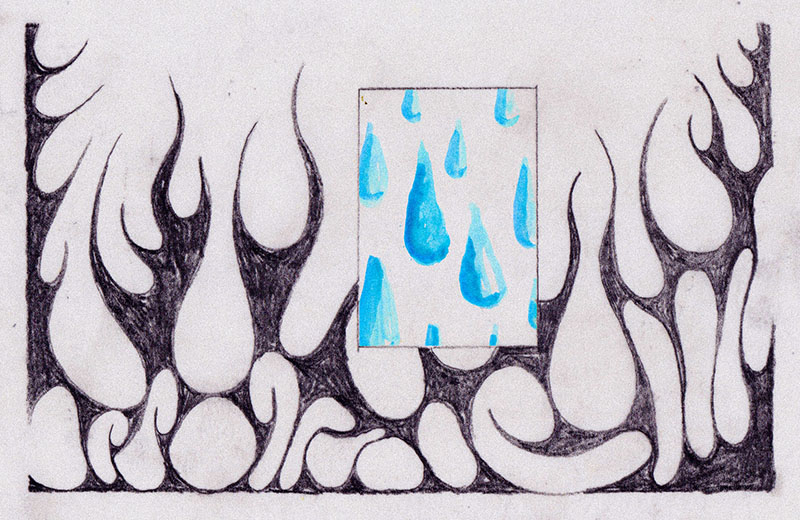

He’s already doing well, the mother told the daughters, who had come to be with their papa in this time of crisis as soon as they found out what was happening. Yes, one of the daughters said, he’s already doing well. Whereas in truth he wasn’t already doing well, he was still doing well, because the next day his condition worsened. He was writhing on the bed, his eyes were aglow, as if a fire were burning inside, the way the jungle burned in Vietnam when the US Army was scorching the land. There was a forest fire in his body.

Say something, my dear, the mother said to him. Papa, we’re here, we love you, the children said, and conquering their fear—because everyone is afraid of such a tormented person—they caressed his face. Say something! And then their father said nuóc. That was all, just nuóc, nuóc, nuóc. What are you saying? Nuóc, nuóc, and once more, very quietly, and then he stopped breathing.

At the funeral the man’s sister represented his Vietnamese family. Most of his other kin were no longer alive, or else they weren’t well off enough to undertake such a long journey for the sake of a relative they knew nothing about. His German friends were there, some of the parents of his children’s schoolmates, and his colleagues at work. His wife, now a widow, listened to the heartfelt stories they told about Antoine, about the esteem in which everyone held him. The sister didn’t speak German and didn’t understand why everyone was laughing so much. The wife, using her English, told her what they were talking about. Oh, said the sister, now I understand. And did he say anything? she asked. She wanted to know whether her brother had left some message for the living. I meant to ask you, the wife said, maybe you know what it means. He kept repeating nuóc. The sister looked at the widow.

Why didn’t you give him water? she said.

Water? the wife said and remembered her husband’s parched mouth articulating that word, the word for water, and she started weeping, the tears streaming from her eyes, and on her face, as during the rainy season in Vietnam, the troughs filled with water.