“An act of pure attention, if you are capable of it, will bring its own answer.”

—D. H. Lawrence

Lagaan, a 2001 Bollywood film, has an iconic scene which captures with precision the visual and audio embodiment of dhyan in its purest form. “Dhyan” is the Sanskrit word for focus, paying attention, taking care or mindfulness. It can be employed in the context of meditation and spiritual texts, in relation to concentration on a mantra and also to point towards the mystical. In Buddhism, dhyan is a stage of deep, focused meditation. In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, dhyan is mentioned as the seventh aspect of the eightfold path to enlightenment. Dhyan is linked to a form of surrendering, a stilling of the mind which allows a heightened state of awareness and presence. In common parlance, “dhyan lagaana” or “dhyan do,” means to be attentive to, to ponder or to reflect on something deeply. It is also a colloquial expression and used in the context of taking care of a person, as in “Usko dhyan rakhna,” or when telling someone to proceed with caution, “Dhyan se.” Dhyan thus encapsulates meditative absorption as well as simply paying attention. The root of dhyan is “dhi,” which draws on the idea of intellectual contemplation distinct from cerebral thinking.

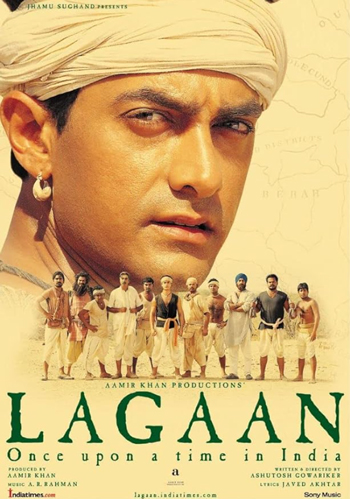

Directed by Ashutosh Gowariker, Lagaan exemplifies the layered meaning of dhyan. The film is set in 1893, in a small Indian village where the inhabitants are burdened by colonial taxes, drought and poverty. The film embodies and converges the various forms of dhyan, particularly in the iconic monsoon scene when the melodic framework of raag Malhar, nature and human emotions climax in a wordless attending to the unknown. Watching the convergence of the forms of dhyan in the film is itself also a form of dhyan, as the viewer focuses their attention on the images before and music around them.

In classical Indian aesthetics, dhyan involves the cultivation of a certain state of being. It requires the ability to have receptive awareness. Dhyan, in that sense, means attunement to nature which cultivates and prepares the heart for a mystical experience. Dhyan thus signifies a form of creative expression, soulful listening and an awareness so that one is fully present to what is being presented in the art form. It also means that the viewer or listener becomes aware of subtle shifts in nature and in themselves in response to the art, and where they are in that moment. In that sense, dhyan is creativity, concentration and a portal to a sanctuary of revered instances.

In the well-known monsoon scene of Lagaan, the villagers stand in silence on the parched earth, watching the sky stretched thin, waiting for rain, their faces lined with exhaustion and hope, their bodies tense with anxiety. The camera captures their angst, moment by moment, as the sky changes. There is a shift in wind as it moves through the dust, and the viewer can sense a scent in the air, a crack in the clouds. Raag Miyan ki Malhar, a classical raag melodic framework, plays in the background, adding atmospheric tension as heavy rain clouds appear in the distance. This moment of waiting is sacred, because the villagers are fully present, and the music is then not an accompaniment but an aspect of the moment itself.

In Indian classical music traditions, every melodic framework or raag reverbates with a moment in time. Raags reflect dhyan to the time of day, seasons and cycle of nature. These are captured and reflected in the lyrics of a song, or its poetic symbolism as well as the beat and rhythm of the melodic framework, which if attended to with dhyan are a gateway to a mystical dimension. The resonance is not arbitrary, but based on the notion that the human body and spirit vibrate differently with the rhythms of nature. To be alert to those shifts is dhyan, a kind of cosmic mindfulness.

For Lagaan, AR Rahman composed “Ghanan Ghanan” using raag Miyan ki Malhar, an established, classical melodic framework which is associated with the monsoon season, to portray the effect of the drought and expectation of rain as a profound emotional and spiritual experience for the villagers. Malhar is a melodic framework which captures the slow, deliberate unfolding of the sky as though it were holding the sky’s breath in its rhythm. The raag is an invocation to nature to bring the promised seasonal rain, by mirroring through musicality the movement of the sky and earth. The raag carries the weight of longing and the hush of anticipation. Raag Malhar has bhava, or a combination of emotions: yearning, love and compassion, which makes the raag mournful and melancholic, but is also exuberant. When raag Malhar is rendered with dhyan and the listener attends to it with dhyan, they are able to appreciate the beauty of the music and their connection with nature, and succumb to the essence of the raag’s atmosphere and rhythm.

The lyrics of a popular song, “Barsaat ke Mausan,” sung in Malhar, emphasise the effect of the monsoon season on a person who has dhyan.

“Barsaat ke mausam mein dhyan lagta hai badalon ki awaaz mein . . . ”

The phrase describes how during the rainy season, attention rests in the sound and movement of clouds. Here dhyan on nature is meditative, emotional and spiritual. According to legend, Tansen, the composer of the raag, had the power to rouse thunder and rain through his rendition of raag Malhar because of the intensity of his concentration on the notes and melodic framework. Malhar uses swaras or notes that reflect and evoke yearning for rainfall and captures the earth’s thirst for rain after a season of drought. As a quiet and receptive listener attunes themselves to the subtleties of the raag, they experience the emotions of the raag. Listening or singing Malhar during the monsoon season is thus likened to an act of devotion.

To return to the monsoon scene: There is no dialogue, only background raag Malhar and the villagers’ collective quiet. Their communal attention to the sky and wind is more than a dramatic pause—it is a kind of shared meditation and a surrendering to nature. After many months of drought and seeing dried-up crops, dehydrated animals and famine-stricken children, the villagers are unaware of anything except what the sky and moving clouds offer—a fulfilment of their hopes or a continuation of their sorrow. They realise they have no choice but to accept nature’s decision, and in that moment, this is also a form of spiritual submission; rain is a grace from the heavens. The villagers’ dhyan to nature is portrayed as a moment of mystical reverence. The scene captures the mystery of what it means to be human—yearning, even while yielding. Raag Malhar playing in the background captures this with melodic force and pulls the viewer into the drama, mirroring the unpredictability of nature, embodying the feelings of the villagers and uniting the viewers with the characters and their stories.

According to Indian Ayurvedic tradition, Varsha Ritu, or the monsoon, nurtures awareness. Ayurveda teaches that the rainfall comes after extreme heat has dried out the earth and the human body. The monsoon is both a weather event and a season inside the human body. The air is heavy, which causes digestion to slow, joints to swell and emotions to soften. Ayurveda suggests the body mirrors nature, and after the intensity of summer, the monsoon rains quench, bring respite and facilitate a natural inward turning, making the body more vulnerable and receptive. The monsoon season is thus best suited to dhyan or witnessing because it offers clarity and a more profound sensing. The rains blur edges, slow time and mute the noise of the daily mundane. This easing of tension allows the body to feel more fully, to rest without collapsing, to perceive without grasping. In this state, life is a sensory experience to inhabit.

Raag Malhar captures this emotional and psychological state of the monsoon. The melodic framework of Malhar’s slow, curved phrases mimic the rolling of clouds, the swell of longing, the hush before release. The beat and rhythm do not encourage a forward movement but a regathering, a circling, a floating and thickening, like dense, heavy clouds. A fullness waiting to be felt. As the raag continues to play during the monsoon scene in Lagaan, the music brings the viewer into the same contemplative space as the villagers. In witnessing their wait, the viewer begins to sense their own quiet aches, hopes and unspoken yearnings. The raag creates an empathetic resonance: the viewer’s breath slows down, they lean forward, and recognise what it means to long for something. The viewer’s body, in the act of watching, becomes part of the scene: their skin tingles and their throat tightens as emotions rise from the plot and characters, as well as from sound and visuals, and the viewer becomes fully absorbed beyond simply watching a film. The raag is heard and sensed in the gut, the chest, the back of the neck. This is another type of dhyan—and the essence of observing. To allow a feeling to pass through you without rushing to label or escape it. To sense with the whole body, to feel every emotion and have the mind entirely focussed. In this way, a scene in a film and a phrase in a raaga awaken a form of awareness and presence.

In an interview, Rahman spoke about how his music was inspired by nature, and in Lagaan he used it to evoke the essence of the monsoon in parallel with the characters’ plight. In Nasreen Munni Kabir’s interview in A.R. Rahman: The Spirit of Music, he elaborated:

“In South India, we talk of the breeze that blows through the leaves of the coconut tree. It has a natural feel and makes the leaves rustle gently. It isn’t the same thing if you shake the tree violently.”

The heartbeat of the village community is also echoed in the simple and expressive choreography of their dance in the rain to raag Malhar through which they emphasise their mutual affection and shared joy. The dance is an aspect of communal dhyan on resilience. It is also a form of embodied dhyan, where dancing is a shared, focussed response to nature. The rhythm of the music and dance mimic the natural sound of rain, creating an immersive atmosphere that pulls viewers into the villagers’ anticipation and relief.

The director Gowariker highlighted in an interview with India TV News, 20 years After Lagaan, (2021) how music was integral to every scene he crafted to convey this:

“From the rousing anthem ‘Baar Baar Haan’, the rain song ‘Ghanan Ghanan’ . . . the soundtrack of the film is an inseparable part of its success.”

And in Widescreen Journal (2009) he explained why he chose Rahman, “The reason why I wanted Rahman was because, you know, Lagaan is a blend of folk music, traditional, classical music (Indian), and western classical.”

His mention of the necessity for the music to be embedded as part of the experience reiterates the wider concept of dhyan, for the characters in the film and the viewers; all are united in a concentrated, shared feeling of elation. The coming of the monsoon rain, in that sense, is a joint spiritual experience, not just a climatic, cinematic event.

At its core, raag Malhar in the Lagaan monsoon scene does two things: it captures the mood of renewal after the rain and it symbolizes salvation. Rain is not only a metaphor for freedom from hardship and drought but also from colonial rule and oppression. Thus, the scene presents a nuanced act of witnessing both the uncontrollable forces of nature and the villagers’ fight for liberation. The villagers’ struggle to win a cricket match against the British cricket team is an act of defiance against the exorbitant taxes imposed by the colonials. It is a struggle for independence, and a triumph of the spirit over tyranny. Their unity, focused strategy and determination to play cricket with dhyan ultimately enables the villagers to win the cricket game. Gowariker remarked on this layered meaning:

“The monsoon scene is not just about nature’s cycle but also about awakening—the stirring of courage and unity among people oppressed for generations. It is about hope taking root in the most unlikely circumstances.”

Aside from AR Rahman’s soulful rendition of raag Malhar, the series of cinematic close-ups also indicate Gowariker’s artistic dhyan. The villagers’ emaciated bodies, dry skin, fatigued postures and slow movements reflect their deprivation and their inhabitation of the parched environment while also illustrating their connection to the soil, the sky and each other. Anil Mehta’s cinematography depicts human sensitivity to nature as extension and reflection of the surroundings, a deep psychological alignment with weather cycles, and longing for a rebalancing with the natural world. When the villagers in Lagaan stop and stare at the sky wordlessly, they are immersed in the monsoon atmosphere. They are attuned to the environment, listening for the language of clouds and wind. Gowariker captures their communal stillness or dhyan beautifully on screen.

Throughout the film, the quiet leadership and solitary moments of the protagonist (Bhuvan), particularly when he gazes at the sky, observes his community tilling the land or speaks to children, embody dhyan. His calm resolve contrasts with the anger and frustration of the British colonisers, suggesting that inner tranquillity, dhyan, is the foundation for collective resistance.

Throughout Lagaan there are other examples of embodied dhyan: the manner in which the villagers practise cricket with resolve and how these ease tensions in the team, and the way in which the villagers’ bodies, strained to the limit and focussed on winning the game and liberation, become instruments of colonial resistance. Like the dance in the rain, these are physical manifestations of dhyan: mindfulness in movement, presence in teamwork, and the embodiment of hope. During the final cricket match, the camera oscillates between intense action and moments of quiet focus, the bowler’s measured breath, the batter’s steady gaze. Through these interludes, the director slackens time, allowing viewers to witness and feel the stakes of the fight. Watching the match becomes another form of collective dhyan where actor and spectator are acutely and present.

Lagaan is not a fast-paced, sensationalised story. It is a film which connects music with cinematic visuals of nature and humanity. The camera lingers on details of the earth, the sky, the villagers’ faces and actions. It pays attention to the rhythms of rural life, the subtle changes that occur in the villagers’ bodies and minds in response to changing seasons, and their emotional landscapes shaped by hardship and oppression. The deliberate, slowed-down drama echoes the concept of dhyan, and invites the viewer to listen to Malhar and witness the monsoon. The gradual unfolding inspires empathy for the protagonists and the realities of their resistance. Lagaan asks for a practice of dhyan as radical presence: an awareness of a shared sense of what it means to be human, alive in this moment together, living in synchronicity with nature and in relationship and empathy with community.