I’m speaking to my daughter. She’s ten years old and has made herself a dreamcatcher: a ring about the size of two hands, hung with brightly-coloured ribbons. They were originally a Native American creation.

“Not since I made that.”

“Do you still remember the dreams?”

“Only one. The rest are all jumbled up.”

She doesn’t want to tell me about that nightmare. Her twin brother, who has been listening to our conversation, chimes in:

“It’s when they take her to the concentration camp.”

“Because of him!” she bursts out. “We were in the playground when someone came over and asked me why my hair was so curly, and if I was a Jew. That’s when he said I was.”

My daughter’s hair isn’t curly. In fact, it couldn’t be straighter; very fine and fair.

Who told her that many Jews have curly hair? Not me. Nor did she hear from me that she has any connection to those dragged away to the concentration camps. Before she was born, her mother and I agreed not to talk about that with the children. I wanted it that way. They were three years old when we split up, and there were plenty of things both before and after that she did differently to what we had agreed before they were born, though of course I didn’t behave the way she imagined I would either. When I raised the issue of our prior agreements, she replied that the situation then had been quite different: She had absolutely wanted children with me, and so would have made any agreement or undertaking whatsoever. Once they were born, however, it was only natural that she should arrange matters as she thought best.

She’s their mother.

In this case she had decided to speak to them about their Jewish ancestry, even though it is not her ancestry. When did she first bring it up? When they were still very small, perhaps four or five years old. I wasn’t present, so I don’t know precisely what words she used, but she must have told them about people being burned:

“They burned your grandmother.”

It was my son who first used that word; that was how I found out that they knew:

“They burned them because they were Jewish. Is it true that . . . ?”

Now my daughter dreams of being taken away. That isn’t to say that my son hasn’t had the same kind of dreams in the past, or won’t in the future.

If some method existed for expunging information from the human brain, I would expunge this from theirs. That way, my daughter would not dream that her hair was curly and they were taking her away to a concentration camp.

I don’t dream about that sort of thing. I have bad dreams, but I’ve never dreamed about being taken away to a concentration camp. Probably because I was older when all that was revealed to me.

*

It was my mother who told me, and she wasn’t Jewish either. I could have written that no drop of Jewish blood flowed in her veins, if I believed there was such a thing as Jewish blood.

I do not, though enquiries into the matter seem to credibly indicate a connection between blood type and ancestry. Among people of Jewish background there is a greater prevalence of people, including me, who have blood type B. My mother did not. If procedures for telling Jews from non-Jews are ever employed again, an extremely accurate blood-type test may be among those introduced. To weed out the undesirables.

*

My mother gave blood often, as have I on many occasions over the years. Jews are more likely to receive my blood than non-Jews. I helped them, because Jews always and in all circumstances help one another, though of course in complete secrecy. Not everyone who makes such pronouncements considers themselves antisemitic. I helped those of my race in such secrecy that even I knew nothing about it. A self-sustaining network.

It was my mother who told me, and the mother of my children who told them. These women were not Jews, but they did what my father and I, consciously or unconsciously, neglected to do: pass on Jewishness. As in a game they picked up a shawl, saw how it fluttered in the wind, then freed themselves from it and tied it to somebody else.

They would have been better off tying it to the branch of a tree.

*

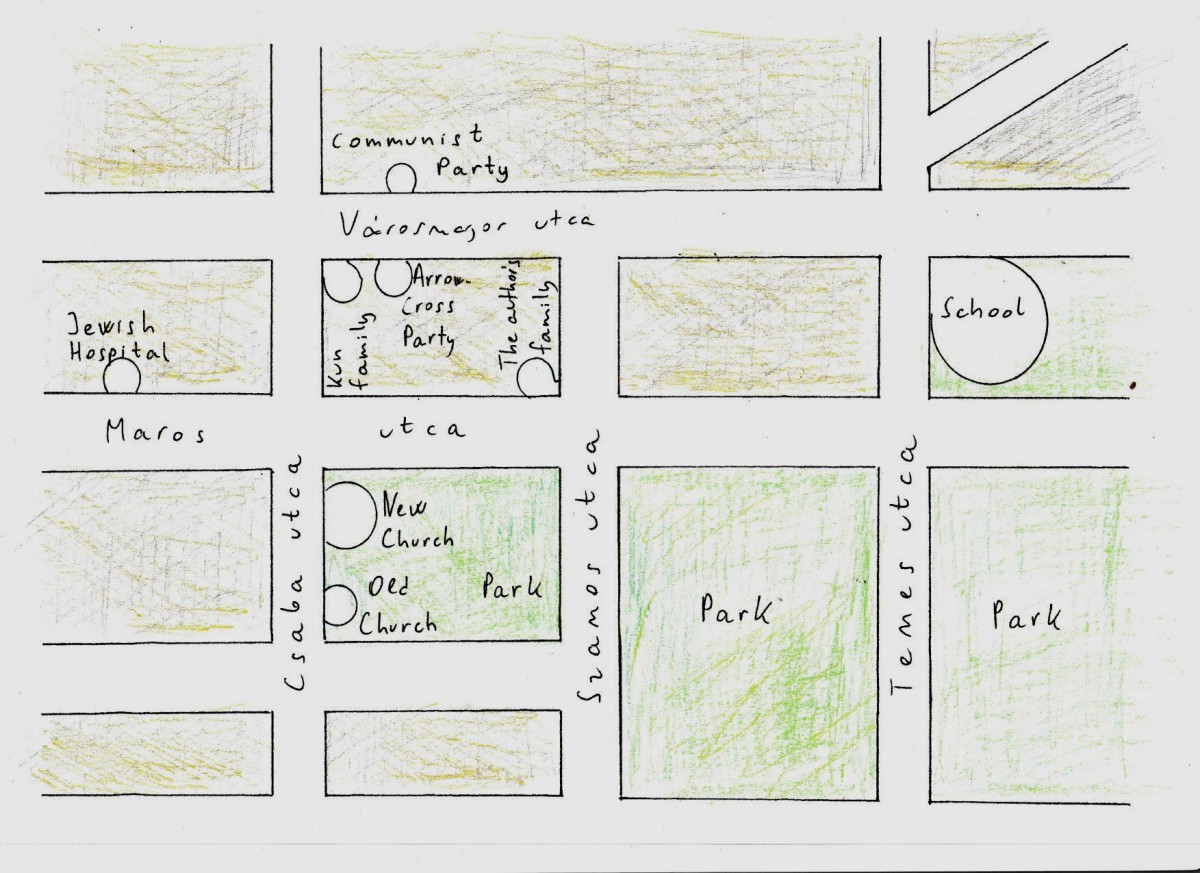

I grew up in Budapest’s twelfth district, in a neighbourhood known as Városmajor, and coming to understand what happened there in the winter of 1944–1945 was a long, slow process. In school, where knowledge flows through the prescribed channels of the state, it was never spoken of, though there were teachers there whom I loved and respected, and of whom my only abiding memories are of their professional excellence. Still, can I summon to mind so much as a single instance when, in imparting the national curriculum, some mention was made of the events that took place here? No. Two did, however, feel the need to speak up when it came to the 1956 revolution. Cleverly, prudently, you could almost say tastefully, they bore witness to the revolution, and recounted brief personal anecdotes. October 1956 in the second district; October 1956 in the fourteenth district. This showed that it was possible to say something of the past beyond the material in the textbook, though it must be admitted that these digressions conformed so neatly to the general tenor of the syllabus—the Soviet Union and socialism, the celebration of proletarian internationalism—that in truth they may have been aimed more at fitting in than speaking out.

I started school on Városmajor utca in 1966, twenty-one years after 1945.

Every year they had us celebrate the Soviet Union’s liberation of Hungary in 1945—eight times while I was at that school—but as for what happened in the months preceding that liberation, on the very streets we walked every day, nothing was written in any textbook, or mentioned by any teacher. If we assume that some of my teachers were around forty years old in 1966, to take merely a feasible and in all probability accurate average, then they would have been around nineteen in 1945. That means they would have been alive then, living and hearing things, and old enough to think. Even if they had not wished to, they must have accumulated memories, and whether they liked it or not those memories must have endured. Not one of them, though, ever breathed a single word about it. Nobody whispered to us, for instance, about the specialist outpatient clinic on Maros utca that had once been a hospital, and the people who were murdered there.

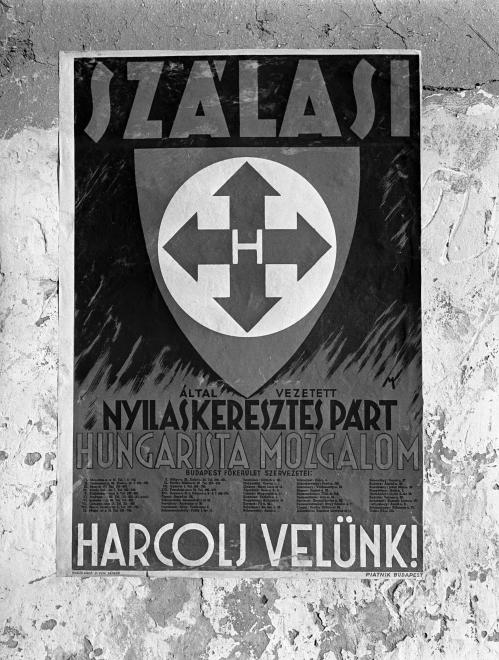

There was no memorial plaque on that building, but there was one on 42 Városmajor utca, because that was where the Hungarian Communist Party had been founded. Every anniversary we were brought there to lay wreaths. That plaque no longer exists; after 1989 it was defaced and soon removed. The Városmajor utca office of the fascist Arrow Cross Party once stood directly opposite; today it’s a car park. If the Communist Party memorial was still there, as well as some plaque or column commemorating the Arrow Cross offices, then the contrast between the two memorials standing face to face might well prove instructive.

I grew up at 40 Maros utca. When did I first learn what happened down the street at number 16? At ten years old, I certainly didn’t know. Nor at twenty. By age thirty, in 1990, I may already have known.

*

The Maros utca hospital was established in 1931. It was called the Budai Izraelita Szentegylet Gyógyintézete, or Buda Israelite Holy Society Health Institute, otherwise known as the Hospital of the Buda Chevra Kadisha. It had specialised surgical, internal medicine, and gynaecological departments, and it treated approximately a thousand patients annually.

Over the last fifty years, this is a building I have walked past more times than I can possibly guess. In outward appearance it looks neither Jewish nor particularly like a hospital—was that perhaps deliberate? There is no hint of seriousness about it, indeed it looks rather friendly and cheerful, and its asymmetrical façade makes it stand out from the houses on either side. Facing it, we see a space to the right with a little courtyard. Passing through the wrought iron gates and crossing this courtyard—an intimate space between the street and the hospital—we come to the entrance.

A marble plaque has been put up inside the building, but it is difficult to understand why—if they wished to shield passersby from knowledge of the horrors perpetrated here—they should foist it upon the sick. Can those coming to see a gynaecologist or psychiatrist read about what the Arrow Cross did between these walls, without its doing them any harm? Or is it simply unimportant?

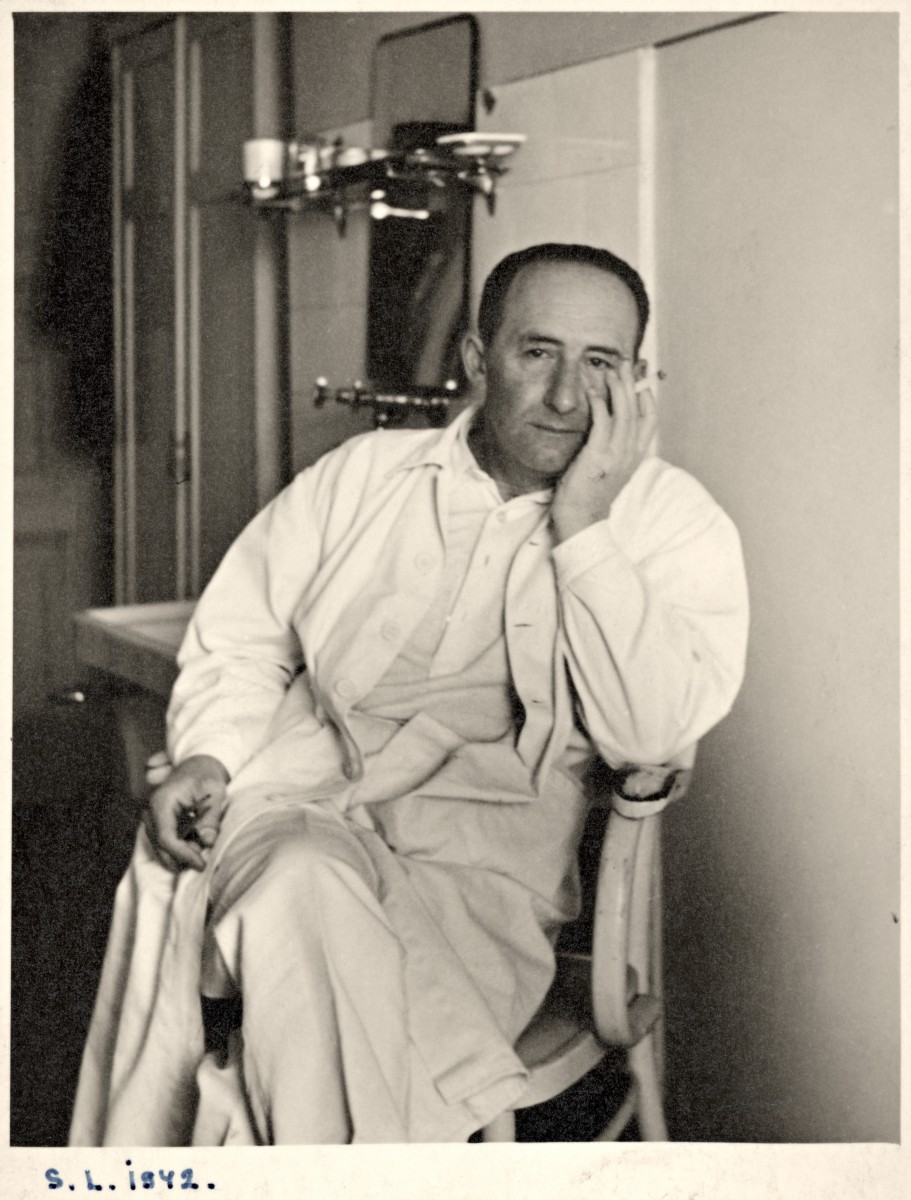

According to the inscription it happened on January 12, 1945, which was a Friday that year. Budapest had been under siege for more than a month and a half by then, so it probably made little difference whether it was a weekend or a weekday. Few people were still going to work—they had given up on their factories, their offices, and their schools. Restaurants had closed down too, but bakers—if they still had their bakeries—kept baking. Bread is important to Hungarians, and in spite of the snow and the bombs they stood in long queues for it. The soldiers and police still worked. The doctors worked. Every report emphasises that the Arrow Cross murdered the doctors and nurses together with their patients. Why wouldn’t they? The Jew doctor is more harmful than the average Jew, since by healing the sick Jew they prolong their life. By assisting at the labour of the pregnant Jewess they help secure Jewish progeny, swelling the numbers of the race. The fascists sent countless doctors of Jewish background to work in forced labour battalions, or shipped them off to be murdered in concentration camps. In one article in front of me I see the name of one of the hospital’s head physicians: Marcell Róth. That was his name. Specialisation: surgeon. He and his wife were both murdered. He had two sons who survived the siege; they were nearby in Bogár utca in the Rózsadomb district of Buda, and thanks to the Lutheran pastor Gábor Sztehlo they were able to find work in an alms house and survive the final few weeks of the war. Once, when they were visiting their sons, Gábor Sztehlo recommended that Marcell Róth and his wife stay at the alms house too, but they returned to their patients.

Marcell Róth was a Transylvanian. He moved to Budapest in 1942.

*

Budapest’s twelfth district is like a little Transylvania: Maros utca, Szamos utca, Temes utca—these Transylvanian rivers seem to gurgle down into the valley, while even Csaba, the Hun-Székely crown prince, is commemorated in Csaba utca. The architects who designed the district sometimes worked in a modern, international style, at other times in a folk Art Nouveau style that relied on Transylvanian motifs. About a hundred to a hundred and fifty metres from the Maros utca hospital stands the little church designed by the Transylvanian architect Aladár Árkay. It is intimate, friendly, and seems to promise sanctuary. A little further off stands the nursery and primary school designed by Dénes Györgyi and Károly Kós, both also Transylvanian, which I first attended when I was eight years old.

At home, the shelves of our apartment are lined with books by Transylvanian authors, amid, of course, many others. There are Székely folk ballads and wood-block lithographs, as well as József Nyirő books in halina-cloth bindings, which date from way back before the war. My mother read him as a little girl. As did I when I was very young, and we loved his stories. Later, after 1989, we acquired a collection of novels by the nationalist and anti-Semite Albert Wass in paperback. Before that it was impossible to learn anything about him, or to read his books, and so I bought one or two for my mother because I wanted to give her some pleasure. It never occurred to me that I myself might read them. Firstly, because I have an enormous pile of books I’m supposed to get through, and secondly because I knew what was in them, and felt aversion to their contents. After my mother’s death, when we came to clear out her apartment, I took these books with me. Years later, together with a few other similar works, I took them to the dump and freed myself of them.

In our family, as in so many others, it was simply understood that the purest form of “Hungarianness” was to be found in Transylvania, and that the most Hungarian part of Transylvania was the Székelyföld or Székely Land. Nobody ever said this out loud, but it seemed to float in the air around us. When the Second Vienna Award returned Northern Transylvania to Hungary in 1940, my uncle took my mother there on a car trip in a red DKW. She kept a travel diary.

In her youth, she had wanted a literary occupation. Not that she pictured herself as a writer—she was far too modest for that—but in some profession where one lives in the company of novels and poetry. A literature teacher, for instance. My grandmother, however, forbade her to study the humanities, so she became a chemical engineer instead, and found satisfaction in the study of chemical compounds. She worked in a research institute, specialising in medical science, or more precisely in the study of physiology. Still, if I wanted to know her sentiments, I did not need to go looking in her travel diaries or letters. When I was in year seven—meaning around thirteen years old in the Hungarian school system—my school awarded me the honour of giving the farewell speech to the departing year-eight pupils. This meant, consequently, that I had to write it. Writing has never been a problem for me; everyone always said that my handwriting was atrocious, but the process of thinking up sentences and putting them together had always gone tolerably smoothly. Even then, however, I was wise enough to show the finished text to my mother first. She said I was very clever, but what I had written still wouldn’t do, since it didn’t have any heart. It is interesting that I did not take this critique too personally, and accepted her help. I knew that I would be incapable of producing a different text on my own. Even at the outset I was a heartless writer, and I have remained one ever since, but with hindsight, I will say one thing in favour of that industrious, thirteen-year-old wordsmith: I did not lie. No bonds of love tied me to any of the departing year eight pupils, so there was no cause for an emotional goodbye. Indeed, I do not remember any of the pupils who left the Városmajor utca primary school in 1973, or rather only one, and only because he was constantly having a go at me, making fun of me, and threatening me for weeks on end. I remember him; he had a German name. Writing about such a topic, in other words, it was impossible for me to be both honest and warm-hearted at the same time. My mother helped me, and she in turn was helped by Sándor Reményik, whose sentimental writings she turned to for inspiration: Mi Mindig Búcsúzunk—We Always Bid Adieu—and works of that sort. Reményik was a Transylvanian poet. I stood in the school playground, with both the pupils and teaching staff lined up in front of me, and read from my paper in a loud, clear voice. There was so much heart in the speech that I adopted a rather cold, declamatory style, just to maintain a degree of balance.

Reményik was not taught in the school, but afterwards nobody ever asked me why I had quoted him.

The old cherry tree which stood in the playground facing Temes utca, and which I absolutely adored, is gone. It was a very old tree, its bark grooved with many an old scar; fresh wounds bled trickles of golden liquid which gradually solidified. Drops of amber. If I’d known then I would have cut some new nicks in the bark myself; perhaps that’s how it came to be so scarred. I remember the tree’s white blossom in spring, and its early-ripening fruit. Back in the winter of 1944–1945 it was already there—indeed it would have already been fully grown. I don’t know when it finally disappeared, nor in what circumstances: Did it die a natural death, at the end of its allotted span? Or did they chop it down before it became a withered husk? Nor am I sure, even if it were still alive, what I would do. Would I really go back to the old playground to find it? Would I wrap my arms around it and ask it to help me see what really happened on that spot, to help me understand?

During the last few weeks of the siege, the school functioned as a hospital. A military hospital. Before the building’s renovation, back when I was a primary school pupil there, the floors were still covered in a kind of oil-based polymer sheet, and the legs of the desks sank deep into the pliant material. If we fell we hardly felt a thing, but our clothes were stained black. Did the wounded and dead bodies piled in the same hall lie on that very same polymer floor?

Though the school building was built to resemble a Transylvanian fortress church, it proved no protection for the surgeon; nor, for that matter, did the Transylvanian church itself. By the time the cherry tree next blossomed, Marcell Róth and the other victims lay buried in the soil of Városmajor.

The man who led the Arrow Cross squad to the hospital was born in the town of Nyírbátor in Eastern Hungary, but came to Budapest from the Transylvanian town of Kézdivásárhely. His name was András Kun, but, being a priest, he was soon known simply as Father Kun.

*

My only grandmother’s health was poor, and she died when I was just nine years old. My mother had to work, so every year the question of what to do with me during the summer holidays—a period of almost three months—caused considerable consternation. She was practically my only family, so I found separation from her difficult to bear. The children’s camp at Lake Velence was a torment to me, as were the elderly couple who took in child boarders during the holidays in their little guesthouse in Csopak, near Lake Balaton. Day camps ultimately seemed a better solution, so I attended an English language camp, and a youth camp in the local district.

I have memories of a sloping field, where we spent our days divided into small groups, and at lunchtime we would all come together in the camp “canteen”—probably the first time I ever encountered that word. The images that come to mind are of thick aluminium plates covered in dents and notches, and equally clunky aluminium cutlery.

The instructors, as a rule, paid us little attention; like us, they just wanted to while away the day. We would split up, and head out to explore the wooded, overgrown fringes of the camp. The land was soon divided up into sectors, then smaller areas which belonged to a group for a turnus, or turn. That was when I first encountered the word turnus, and it resurfaced when I was reading about executions: the Arrow Cross often called a small group of prisoners taken from a larger batch to be shot a “turn” or turnus of prisoners.

I remember the undersides of the bushes too, where we used to steal away and make hiding places for ourselves. Flattened earth and little arrangements of white stones. One boy collected bees, then killed them. This sounds like a somewhat risky pastime, but it was really nothing of the sort; there’s a knack to it. All he needed was an empty box of matches, then he slid the container out about halfway or perhaps a little further. His thumb rested on the matchbox sheath and the index finger on the container, as on the trigger of a gun. Whenever a bee landed on a flower he would wait until it was fully engrossed in gathering nectar, then extend the open lid of the matchbox towards it. If the bee did not fly away in time it was simply a matter of sliding the matchbox shut on it and it was caught; you could hear it buzzing furiously inside. Matchboxes were not made of cardboard in those days, but of thin wooden panels, with brightly-coloured pictures stuck on the lid. These were generally advertisements for some big state-run enterprise, or even admonitions or exhortations from the state. If you soaked the matchbox in water you could peel these off and collect them like stamps. The execution was conducted as follows: The boy would slowly push the container out, just enough to create a little sliver of an opening. Noticing this chink of light, the bee would hurry towards it, thinking it had found a means of escape. The boy would make the opening fractionally wider, just enough that the bee’s head—but only its head—could fit through. Its thorax and abdomen would remain stuck inside. After that it was just a case of sliding the lid shut again and crushing the slender neck against the matchbox lid, ultimately severing it. The beheading was complete, and the matchbox fell silent. In another box he collected the severed heads, but I think he threw the bodies away. I watched him during those long, hot summer days, and listened to his stories. They were usually about what had happened during the war. He would talk, for instance, about how they used to “shaft women with truncheons.” “At first they liked it, it felt good,” he said. “But when it went further up them they’d start screaming. Didn’t do any good, of course; they didn’t get any mercy.” Now, whenever I read about what happened in the Arrow Cross building, I think of that boy. Of course, it’s possible that he simply invented all this “shafting,” but I somehow think it more likely that a father, grandfather, or uncle regaled him with tales of the “good old days.” They did not arrest all the Arrow Cross members, after all, and not all the arrested members were convicted. Even among those both arrested and convicted, only a small minority were actually sentenced to death, and many death sentences were later commuted to life imprisonment.

*

This language is not my own. I use the language of murderers to speak of murderers. I cannot see the freshly-dug graves or the broken, beaten bodies, but the words themselves pass in and out of me, each smeared in filth and reeking of lies. Is it a form of twisted compensation that the link between those bees—méhek—slaughtered on long summer days, and the wombs—méhek—violated with rubber truncheons during equally long winter nights, exists in the selfsame Hungarian language?

Hungarian words . . . In the Buda Castle District, a member of the resistance was violated with a piece of wood. Perhaps there simply wasn’t a rubber truncheon handy, but I think it more likely that the pribék—the gallows man—took special pleasure in the rough, uneven surface of his implement, and the splinters. Pribék! What a word! Pure Middle Ages, though during 1944 and 1945 it was used fairly frequently. Long-forgotten words or expressions from comparable epochs bubble to the surface at such times, like the darkly evocative felkoncol—to put to the sword—which often cropped up in Arrow Cross proclamations and communiqués.

Lazily, I write that the people of that period used certain words, though it could just as easily be the other way around and the words used the people instead. The very people who consented to employ them, or even rejoiced to find these antique terms once more in common use, found themselves in turn consumed by them. Reptiles slithering from their deep caves.

*

All I needed was a single book; a book in which the story of what happened here was written down with the requisite detail and accuracy. Reading it, my own memories would have been enough to evoke the places, and I could have let the boundaries between the two worlds blur and fade, and notice how this process takes place. I never found that book. Such books and articles as did exist were full of striking omissions, imprecise language, and contradictions, though at the same time they almost always contained some clue which led me onward. It eventually transpired that the state archives contained documents on the operating procedures of the Arrow Cross, but that these archives—or at least a large part of their contents—were not publicly accessible. I needed an official recommendation, and it was some time before I was granted access to the old files.

*

Months ago, I wrote that I don’t have Jewish dreams. I do now. Not of being stripped and beaten, though perhaps those will come with time, but of being a shadowy figure, restlessly seeking and probing amid a mass of equally shadowy figures.

I’m not making a dreamcatcher.

By day, I waited for my official permit to access the restricted documents in the state archives. One afternoon I took a walk; I wanted to find and photograph a site of great importance in the story of how the Arrow Cross seized power. This was their “headquarters” and “secret arsenal.” The address was 10 Pasaréti út, in the second district. I had read that long before the coup of October 15, 1944, the Germans had begun supplying weapons to the Arrow Cross, and this is the only storage address officially listed. What is certain is that the Arrow Cross knew about this hidden hoard and, like children well aware that their parents have wrapped presents and placed them under the tree, they spent months yearning for that moment when they could rush over and unpack the shiny playthings the Reich had bestowed upon them.

Number 10 is at the end of Pasaréti út, close to Szilágyi Erzsébet fasor (previously Malinovszkij fasor, and before that Olasz fasor). The building turns out to be a rather run-down old villa standing in a small garden. Despite its dilapidated condition it is clear that this is not only a building of historic significance, but also of considerable architectural merit. Some of the capitals atop the ornamental pillars in the garden wall are either damaged or missing, but in their day they must have looked down upon excited Arrow Cross members as they slunk their way into history and on the stacks of weaponry being hauled out of the garage into the daylight.

Looking for information about entirely different houses later that same day, I stumble upon the fact that this villa was also designed by Aladár Árkay, the architect of the little church on Maros utca. Looking at them again, the resemblance is really quite striking.

In fact, Aladár Árkay’s houses are the stage sets of Hungarian history: for instance, it was he who designed the house on Városmajor utca where in 1906 the Communist Party of Hungary was founded, and the Buda Vigadó, which he designed together with his father-in-law Mór Kallina, was where seven smaller parties formally united to form the National Socialist Party of Hungary in 1937. As a charming backdrop to his own family villa, which stands just beyond the Alma utca retirement home and the Bíró Dániel hospital, he also designed (together with his son Bertalan) the Városmajor church in which the Arrow Cross leader Father Kun preached and performed marriage ceremonies, and where Major László Vannay and his soldiers later set up their base. Árkay also designed the Babochay villa, on the corner of Andrássy út and Heroes’ Square, which is now the Serbian and was formerly the Yugoslav embassy; it was here that, before his execution, Prime Minister Imre Nagy sought refuge when the revolution failed in November 1956.

I set off for home but almost immediately, next door at number eight, I spotted another surprise: on the wall of this newly renovated building is a plaque stating that it used to belong to the film star Pál Jávor. For some time, I had been aware that he first lived in Kék Golyó utca with his wife and his wife’s children, then moved from there to Pasarét. What I had been missing were the precise street name and house number. I knew too that the right-wing press of the time used to print exposés, listing the people who attended private performances at his home: Jenő Heltai, Béla Reinitz . . . I see now how little effort it would have taken the Arrow Cross to keep an eye on him. How defenceless the poor actor was! And how could he ever have escaped when the Gestapo came looking for him in March 1944?

So we rub along, feeling for a thoughtless moment or two that we are free, believing that we can choose whom we listen to, whom we talk to, whom we love, while from right next door our deadliest enemies, our neighbours, are watching.

*

Father Kun was also practically a neighbour. I pictured him differently, as a sort of nomadic lord on horseback, blowing through the city like a hurricane before moving on, but it turns out that he actually set up camp on precisely the same block I grew up on. This was one of a series of large, brick-faced structures, with our apartment at number 40 Máros utca looking out on a street corner, while at number 33, diagonally across the block from us, lived the Kuns.

The word “block” has a different ring to it today than it did back in the sixties and seventies. During the dictatorship the block was both a unit of organisation and of surveillance. Whenever we applied for a passport, for instance, we had to present ourselves at one of the block’s few private apartments. An older man lived there whom we did not know, but who certainly knew all of us. He was always keeping an eye on us, but in the event that he did not deem us guilty of “serious antisocial expressions” he would grant our request. Those were the good old days, when people still looked out for one another, those “public guardians” might say, but I have my suspicions that even if the housing block surveillance system is a thing of the past, there are still those who make it their business to keep an eye on us.

The Kuns first appeared in August 1944. I say “Kuns” because Father András Kun did not move to Budapest’s twelfth district alone. He organised the allocation himself, but in his parents’ names. They, Károly Kun and Mária Vasas, had moved from Nyírbátor to Budapest at the end of the thirties. His father worked as a concierge in Váci út 16, close to Nyugati railway station, until it was destroyed by a bomb which strayed (slightly) from its intended target. This building had been a large apartment block with two inner courtyards, and the concierge’s apartment was on the ground floor of the second, narrower courtyard.

By 1944, however, many thousands of formerly Jewish-owned apartments were freed up for the sake of Christian Hungarians “in need,” and in June 1944, it was officially decreed that these so-called “yellow-star houses” could be occupied. Father Kun’s parents moved six stops along the Number 6 tram line, not far from Széll Kálmán tér, and this spacious, three-room flat with all modern conveniences (and indeed all its former furniture, which the former occupants had been forced to leave behind for the use of its new “Hungarian” occupants) must have seemed a significant step up in the world for the former concierge. Father András Kun was clearly greatly influenced by the fine carpets, and even managed to weave them into one of his fiery proclamations: “When they break into one of their richly-carpeted rooms . . . ” That is, when the sons of the people enter the homes of the Jewish bourgeoisie.

*

Writing of my teachers, I said that they never spoke about what took place in my part of the city. That’s true, but a little while later the words of an older male teacher with a moustache came back to me. If we were not careful, he said, others leaner and hungrier than ourselves would come and chase us from the district. It was as though this noble quarter of Buda was the country’s most exalted space, the stage for some eternal game of “king of the hill” which every ambitious Hungarian endeavoured to win, and in which we might at any moment be driven from our perch. (The latest figures seem, incidentally, to confirm this surmise: the twelfth district tops the table for average income, and for primary school performance.)

By 1944, Father András Kun had already abandoned his plans to become a Franciscan monk: it was no longer the leaders of his order that he looked upon as spiritual mentors, nor the officials in the Vatican he respected as leaders, but rather Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Ferenc Szálasi. Still, perhaps even at this late stage it was not quite determined that he would become the almost theatrical embodiment of evil he eventually transformed into. At thirty-three years of age—the “Christ Age”—something within him shut down, and he decided he had to embark on a new path. The bombing of his parents’ home, and by none other than the wicked, hostile Anglo-Saxons—whom Father Kun baselessly presented to his Hungarian congregations as mere tools of the Jews—and the sumptuous apartment with which a righteous nation subsequently furnished them reinforced his anti-Semitism, his ardour, and his thirst for action. Still, to become what he finally became, he first had to meet the Arrow Cross members of the twelfth district.

*

The Magyar Nemzeti Szocialista Párt, or Hungarian National Socialist Party, came into existence through the union of seven smaller parties, and a twelfth district branch of the MNSZP soon opened an office at 1 Győri út. “The reporting members stood beneath the newly constituted flag with tremendous zeal,” was how the party newspaper later described the opening days. “Donations of money and furniture soon allowed this branch to begin functional operation, and day by day the number of members grew, until the time came when those hoping to join had to form a queue to process their membership applications.”

All this is largely thanks to a round-faced, grey-eyed man with greying hair and moustache. His name was Csaba Gál, and he was born in 1892. His family reportedly moved from the Székelyföld to Pomáz, a town just north of Budapest. His father died when Csaba was young, and the family had to survive on limited means. He attended evening classes in mechanical engineering at a technical university, while making ends meet by working as a sewer cleaner and security guard. He served as a soldier through the entirety of the First World War, and was wounded three times. By the time of his discharge in 1918, he had been promoted to lieutenant, and received both the greater and lesser silver medal for valour. He was admitted to the Order of Vitéz, but only found work as an ironworker in the Budapest transport authority in 1926, three years after qualifying as a mechanical engineer. He was later promoted to the engineering department, and became a technical advisor. He was one of the original members of the National Socialist Party of Agricultural and Industrial Workers, founded by Zoltán Meskó in the early 1930s, and through the union of 1937 became a member of the MNSZP. The Meskó group within the party proved an engine of National Socialism; it was they who first used the arrow-cross symbol which later came to represent Hungarian fascism. Despite this, Meskó himself later withdrew from the Arrow Cross movement, and ultimately disapproved of the German invasion. Those among his followers who inclined more towards Gál’s implacable radicalism gravitated instead towards Szálasi.

Despite the fact that Gál himself lived in the eleventh district, he was elected leader of the party’s twelfth district chapter. It is important to understand, however, that back in 1938, our district had not even been born yet; the capital was merely, so to speak, pregnant with it: A law of 1930 stipulated that—among other legislative changes touching the administration of Budapest—the ever-growing first district would be split into several parts, and with the addition of various areas previously outside the city, these new parts would become the eleventh and twelfth districts. Since the infrastructure for administering these new districts had yet to be built, the new units of municipal governance could only enter operation in a gradual manner. The last to begin functioning was in fact precisely the twelfth district, when the council office on Böszörményi út opened in 1940. When Csaba Gál took over the operation of the twelfth district chapter, even the first district or “mother district” had neither an office nor even a permanent meeting place. There was, therefore, no common organisational basis on which it was either necessary or even possible to distinguish between these developing districts.

Like a wartime general, Csaba Gál’s index finger traced circles over a map of Budapest. Where should their headquarters be located? He did not want to be too far from the first district, and thus from the castle and the heart of Buda. At the same time, even if he did not intend his new headquarters to stand directly next to the new district administrative offices on Böszörményi út, still it ended up in cautious proximity to it: Győri út is between Krisztina körút, which marks the edge of the first district, and Böszörményi út; neither are more than a few minutes’ walk away. The building in which the first district administration rented offices was in the historic Krisztinaváros neighbourhood, which rises above Déli railway station. This made it accessible both to those arriving by train and to those who worked in the surrounding railway yards. The triangle enclosed by Alkotás utca (then Gömbös Gyula út), Csörsz utca, and the railway tracks approaching Déli station (which includes Győri út) is not typical of the twelfth district: many of the tenement blocks here would not look out of place in one of the less elegant districts of Pest, and there are many workshops of various sizes in the area. The most notable among these was the famous Süss Works, by then already the Hungarian Optical Works, many of whose workers lived in the vicinity. The district leadership could count on the badly paid, dissatisfied workers in the local health institutions sooner or later finding their way to the registration office, while those from more affluent areas further from the centre who sympathised with the Hungarista cause would surely not mind the inconvenience. Even those from the furthest-lying regions in the Buda Hills would surely make the pilgrimage to Győri út if it also meant a trip into town.

“My job was to organise the district, both from a numerical and an ideological point of view. This appeared a truly daunting task, seeing as it was an entirely new district with only one or two members and no permanent office. After my appointment as district leader I immediately rented out the offices at 1 Győri út, and set about recruiting new members. This proved so successful that within three months I was able to enlist one thousand five hundred new members.”

(In May of 1944 the number of members was less than half that. Several reasons may explain this drop, but in my opinion the most important was that, as a party planning to stage a coup, they could only tolerate truly determined and able-bodied members, and so weeded out all those deemed insufficiently committed. The membership files were duly purged, just as the Communist Party would purge its own lists shortly thereafter.)

The fact that the Arrow Cross was active in the area even before Gál appeared on the scene is attested to in contemporary newspapers. An article was written in Népszava, for instance, claiming that “[i]t is common knowledge in the Farkasrét area of the twelfth district that the local centre of Arrow Cross/Nazi propaganda is the Metzger farm. This is the home of retired rural constable Ágoston Metzger and his three sons, who hosted continual meetings of Arrow Cross members, and apparently even established a labour camp on the site. When the Metzger boys saw that this provoked no backlash from the authorities they embarked on a more violent course of action, organising irregular squads of boys which for a time continually disturbed the tranquillity of this suburban area and its residents, as well as those tourists seeking relaxation outside the city.”

In response, Összetartás or “Unity,” the Arrow Cross weekly, published an article on May 16, 1937 which said that the Metzgers were indeed Arrow Cross members, and did host meetings on their farm, but claimed that Jewish communist tourists frequently attacked their property. On such occasions, if necessary, they defended themselves.

So here already, at the very outset, were the “boys,” a term at once revealing and euphemistic, which would later become such a frequent piece of Arrow Cross vocabulary. They fought as a way of life. They signified certainty. As a graduate and a decorated war veteran, Csaba Gál offered to both skilled “men of quality” and simple labourers the chance to become part of a common movement which sought urgent and comprehensive social reorganisation. He himself was a Transylvanian Székely, thus more authentically Hungarian than any mere citizen of Budapest, but he welcomed the support of both the German-speaking and Hungarian populations of the district.

Some of the industrialists and merchants in the area were only too eager to free themselves from Jewish competition. With advertisements of the following sort they supported the Arrow Cross newspaper, and gained new customers from among a readership which at that time was expanding every week:

Men of Buda!

Men’s headwear at LENZ

I. Dist. Krisztina körút. 83. (Bors utca[i] 4 on the corner)

10% discount off the listed price

World famous Somló wines! Erdődy wine cellars I. Dist. Bors utca 18 .

Telephone 157-971

Discount for our readers.

The ranks of protesters at the MNSZP’s frequent demonstrations were made up of quick-tempered proletarians, petit bourgeois, some German-speaking youths accustomed to tussles, and a few leaders like Gál with experience as wartime army officers. The largest of these demonstrations took place on December 1, 1938; as a consequence of this violent protest, which the government officially labelled an attempted coup, Szálasi was imprisoned and the MNSZP outlawed. During pitched battles between protesters and police there were many injuries on both sides, and the city sustained considerable damage. The violence unleashed by the authorities against these “men of Hungary” even led to the death of one protester, and another, József Rédli from the twelfth district, died later as a result of injuries sustained during the riot. This, at least, was the view of his large family and many friends, who never forgot his memory. They had to wait six long years until every drop of their comrades’ blood which stained the city streets could be avenged with others’ blood by the bucketful.

*

When the party organisation was being established, András Kun—still in his twenties—was studying in Italy to become a Franciscan monk. Amid his philosophical and theological studies, he became enthused by the dynamism of the fascist Italian state. These immediate sensory impressions were deepened through reading; by way of Mussolini he came to Hitler and Mein Kampf. It proved easy for him to reconcile the teachings of Saint Francis and the National Socialist idea.

At the same time, in Budapest’s twelfth district, construction was nearing completion of the church in which, a few years later, András Kun would stand before his parishioners and conduct marriage ceremonies for young Arrow Cross members. Aladár Árkay’s son Bertalan and the ceiling fresco painter Vilmos Aba Novák, together with most of their fellow artists, worked in the same spirit of union with the fascist masses as their Italian contemporaries.

Perhaps there are no works of art I have spent more time gazing at that those in my local church, for that was where I was regularly taken as a small child. That was where I received First Communion, where I confessed and took the sacrament.

*

In the playground someone spoke to my daughter, asking her point-blank if she was a Jew. She was afraid, and could not speak, but my son told them that she was, and they were taken to a concentration camp. That’s what I wrote down not long ago. It was a dream, not mine but my daughter’s, but still its force was enough to provoke me into a deeper exploration of Városmajor’s hidden past; now things have reached a point where all the things of the world interest me only inasmuch as they connect with this blood-soaked plain, and the lives that sprang from it.

The fact is, however, that the scene where the dream took place, as it were, is not even nearby: my ex-wife moved to a small Austrian village with the children. The people there are, I hear, peaceful and friendly, as is the playground. The children say so too, and there is no visible reason why it should be transformed into the scene of nightmares. That is precisely why it is so strange that in the imagination of a ten-year-old child, between the playground swings, the gates of the concentration camp should swing open.

Later I learned that before 1945 there really was a camp precisely on that spot. The barracks were torn down and the ground flattened, then later a playground was built on the same site. Perhaps the kids heard something about it; there’s no need to suppose anything mystical about the dream. Their proficiency in German is still fairly limited, but certain words are capable of crossing the barriers between languages. Still, they must have carried something within them to have been touched so sensitively by the past of that pretty little Austrian village. Something from here, from Budapest, from the twelfth district.