Vallarta, Jalisco, August 16, 1967

Dr. Ricardo Guerra

Av. Constituyentes 171

Pick up boys tomorrow afternoon my mother’s house have a good trip.

Lilia

Mexico, D.F., August 25, 1967

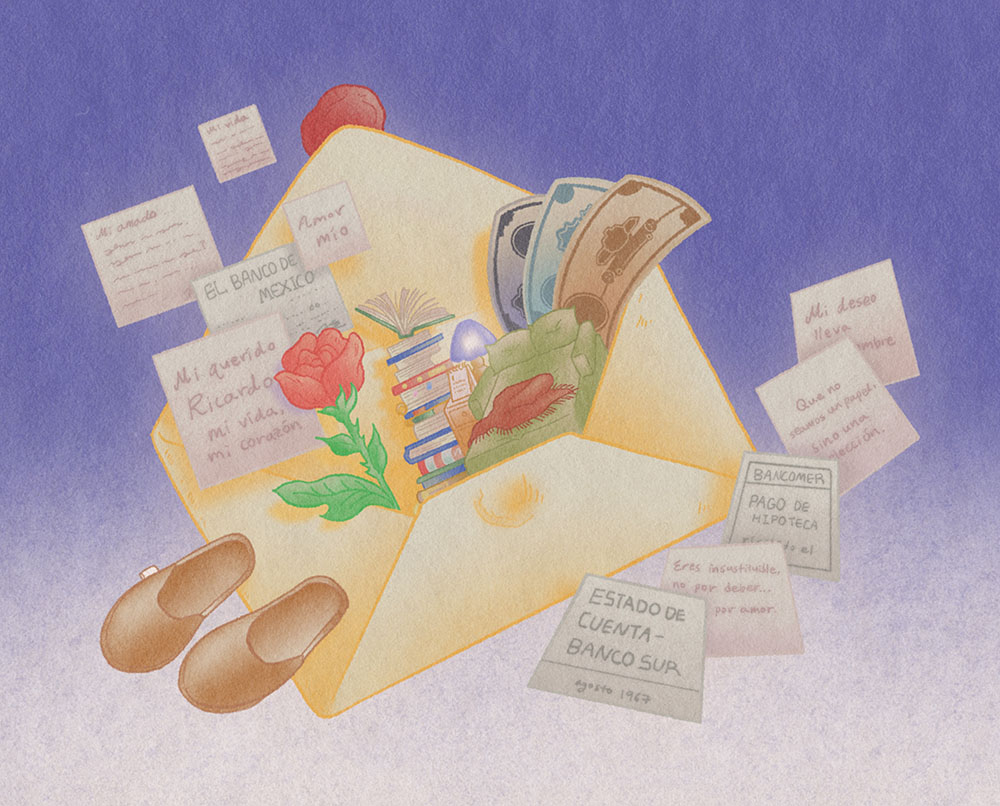

Dear Ricardo, mi vida, mi corazon, I’m so happy we could talk on the phone, and to know that you arrived without any incident and you’re doing well, that it’s beautiful there and that you’ll take advantage of your free time after classes to enjoy yourself, rest and, most importantly, detoxify from Mexico, the house, the family, all the problems here, and the boredom of the daily routine. You say you’re still worried about specific problems, not to mention everything else, and I can assure you there’s absolutely no need for concern. Everything’s working perfectly and I’ve done my best to comply with all your requests so that no problems arise which could prevent things from running smoothly. This past weekend we went to Cuernavaca, I gave José Luis money to pay the water bill, and I gave don Pedro his weekly salary. I also arranged with Nico to give the house a very good cleaning, specifying it would be a one-time thing and, under no circumstances, become something regular. When one needs something from her, she’ll get paid and that’s it. I’m writing all this down for you to look over when you get back. This weekend, only Herlinda, Gabriel and I went to Cuernavaca because, as you know, Ricky and Pablo had been planning to spend time with their mother. On Tuesday, very punctually, Ricky came over for lunch. Pablo never showed up. He had a stomachache and hadn’t gone to school. I suspect, independently of the stomachache (very believable—he has a ferocious appetite) there was a problem with his clothes. Lilia had called the day before asking if by any chance Pablito’s pants and other things he needed for school were over here and, as you know, the boys had already taken all their things to their mother’s house. This same Tuesday, the twenty-second, the date on which the check for eight thousand pesos that Willie gave you could be cashed, Gabriel and I drove to Cuernavaca, very energetic and very early, and deposited Willie’s check in your account at Banco Sur. His check in addition to one of mine for two thousand pesos makes a total of ten-thousand pesos, which is what you recommended I put into that account. Then I got the mortgage notice from Bancomer, and I deposited the required amount in my account at Banco Comercio so that the payment wouldn’t be late. It can be covered from that account and so can the monthly water and gas bill.

As you can see, I’m trying to be the very soul of efficiency, and all of this I do installed in my powerful Opel that I love more every day, and every day we understand each other more deeply. Ever since you left, I’ve tried to park on the patio where you used to keep the Mustang because I think it’s easier and more convenient. I’ve also become an ace at parking in very small spaces.

Last Friday I went to the offices of the Ministry of Education, and the scholarships for Pablito and Gabrielito are all arranged. I spoke personally with Yáñez, who alluded to I’m not exactly sure what, and, if I’ve never been comfortable asking him for explanations, I was hardly going to begin with this minister whose style is baroque and rather obscure. If my interpretation of his enigmatic references is correct, I believe there’ll be some good news (money in sight), but I don’t want to harbor any illusions until I see it.

Speaking of money: the very day you left I got my check from Colorado with sixty dollars more than I had calculated, and I deposited it into my account where they noted it as effective immediately. I believe it’s what you call “certified” or something like that. That same day there was a long-distance call from Guadalajara from a Señorita Irma who said she would call you at the end of December or the beginning of January.

There have been no other calls, no letters, except for some very large envelopes from the University Council that I’m keeping for you religiously.

I organized your papers, and your studio is now magnificent and ready. We vacuumed even the tiniest of corners, we sprinkled insecticide around, etc. I’m going to buy, as soon as they pay me at the uni, so as not be caught unawares in any emergency, a sumptuous queen-size sofa bed, so that the problem of you needing to sleep without being disturbed by the noises from the rest of the house will be resolved. It will all be very comfortable. You’ll have a bedside lamp, an ashtray, a place to leave your clothes, a coffee pot ready to turn on when you wake up, your slippers, etc. And, whenever you like, I could go up to visit you to talk (even though you know very well what my topics of conversation are reduced to when we’re together and alone. Tremble and prepare yourself, because around here they call me the insatiable one.)

I feel sad knowing that you’re so far away, and I miss you very much, but when I think of the future, I feel very optimistic. I love you like I’ve never loved anyone, and it’s my intention to love you even more in the ways that you need to be loved. At times I think it’s a true miracle that after making so many mistakes (I’m thinking of mine, the only ones that are within my ability to amend and overcome), I still have the opportunity to make changes. The very fact that I’ve been able to overcome my sexual problems and so fully enjoy myself with you makes me feel more secure when I think about how we’ll treat each other. There are many things that we share and others where we diverge completely. This we established from the beginning, but we performed a disservice in wanting to, alternatively, mold ourselves to the other’s existence. When you left, I felt very angry for being left alone and, at the same time, very guilty because I didn’t go with you. Now that we can talk much more frankly, we know that with certain relations and with certain friendships, we’re very much more at ease as isolated individuals than as a couple. It would be wonderful if we could adopt this position and choose what we would like to share and enjoy in each other’s company, and it would be good if there remained a margin where we wouldn’t be hurting each other or infringing on each other’s basic rights. I’ve given a lot of thought to fidelity. Not even in my dreams would I wish to, nor could I, demand this of you. Now and then, I’ll be overcome by an attack of jealousy and I’ll make a scene but, thanks to the automatism of my moods that I’ve now been able to observe with much greater precision, I would most likely make a scene with or without any motive. You must be patient with me, and you mustn’t take me seriously, because I’m going to forget my good intentions. I always do. During the time we were together, I experienced moments of extreme anguish because I was afraid I was going to cede to violence. I’ll no longer be possessed by this fear because I feel confident that I’m not going to feed my violent impulses with rationalizations that are based on what you should or shouldn’t be doing and while I put up a front of anger and resentment. And then when I believe I can no longer avoid falling victim to this tendency because I’ve weakened or my resolve has diminished, the fall won’t be as serious, and you’ll help me, which will result in the least possible negative consequences. This is not to suggest you avoid behavior that could trigger my moods. They come on independently of what goes on outside. I mean to say that when you see things are getting worse, you leave me alone to vent however God wills or by turning a deaf ear to all the stupidities that occur to me.

There’s something I would like to ask, and I think now, from a distance and with you being in a new and unfamiliar place, etc., would be an opportune time and perhaps a little easier than when we were together. I ask that you try to divest yourself of the concept of “wife,” a designation that you find so loaded with negative connotations when it refers to me, as if the designation “wife” and myself were the same indissoluble reality. It’s true that I am your wife, but I would like to be so in the truest sense of the word. The person in whom you confide, your faithful and unconditional companion, your friend, the one who creates together with you a strong community in which the boys can grow, a comfortable place to live . . . specific times to be together. When I’m saying this to you, I’m not speaking from a position of absolute conjugal authority, I’m not trying to impose my institutional privileges, I’m not trying to violate your freedom, at least not in any forceful way. If I ask you, for instance, that we talk, that we spend some time together or something along those lines, it’s not to exercise my authority. It’s because, independently of being your wife, I’m also a person, a person who’s in love with you, who needs you, who wants to give and receive love. If I asked of you the same as a lover would, you would interpret it differently. Please don’t think of me as the incarnation of this institution that you reject by throwing away or losing your ring. If I have been that, as your wife, for ten years, apply your Sartrean doctrines. Don’t look at me with a cold, objective stare but look at me as if I were someone different. Someone who has changed, who has undergone an evolution and finds herself with a new attitude. I believe that if you think of me in another way, it’ll help me by forcing me to behave in a way that allows us both to feel better.

I agree with what you said in your letter about the need to maintain our relationship fundamentally for ourselves. If we think of it the way we talked about it, as revolving around the boys, it’s much more likely for tensions, misunderstandings and frustrations to arise. Also, it would be artificial. I want to live with you for you. I understand that now because I’ve lived alone and because I haven’t “needed” you to resolve my daily problems, or to come to an understanding with Gabriel or anything of that kind. What you give me you give me as a man, as the man I love and as such you’re irreplaceable. These last few days I believe I’ve acquired a very clear notion of what constitutes fidelity. You know I was left here with the taste of honey on my lips because I was just discovering the delicacies of sexuality. When you left for Puerto Rico, I felt, in this regard, abandoned, not to mention very needy. I also realize that if one closes one’s eyes, it’s very easy to deceive one’s appetite and satisfy it. But I don’t want to close my eyes, I don’t want to deceive myself. I love you, and this lends a specific meaning to my desire, a desire only you can satisfy. I don’t want anybody or anything to come between us and this new reality that for me is so rich and important. Also, loving you, I wouldn’t want to hurt you, even though you tell me that it wouldn’t bother you and that it would be preferable if I chose a lover so I could understand, etc. One can only imagine that I can understand a priori. I prefer to exercise my imagination rather than my experience. I would prefer (even though I could do the contrary) to belong exclusively to you. It’s very much to my predilection and my feeling of happiness and my sense of pride and security knowing my body only knows the pleasure you’ve given it. And I wait very patiently for your return. I love you, mi vida. Please don’t ever deny me the minimal amount of time together that some of your friends have denied their wives with the all too well-known results. And think of me not as your wife demanding her conjugal debt, but as the woman in love with you who wishes to say by her gestures, her acts, what can’t be expressed in words.

Please don’t think I’m holding out hope that when you return you will dedicate all your time to me or that we’ll be holding each other’s hand all night and day without ever letting go. No. I think, in addition to the radio programs that I do trust won’t be as intensive as they were during our brief time together, everything else will remain unchanged. Your schedule will keep you busy at night. Our weekends in Cuernavaca will be much more flexible because I can take the boys and bring them back without the need for you to go with us—only when you want to. If you do accompany us but have other obligations pending, you can come back early, and you’ll no longer need to go pick us up, which should be a lot less tiring for you.

And speaking about daily business, I believe that your trip has been very beneficial in the sense that it’s allowed me to relate to the boys in a much more direct way. We’ve eaten very well; we talk and make plans. Next weekend, on Saturday afternoon, after Ricky’s classes, we’re going to Cuernavaca. We’ll stop at the Casino de la Selva for a little while to swim, and then we’ll go to the house. We’ll still have all of Sunday and then on Monday, very early, I’ll drive back so the boys can get to school on time.

I called Popoca to ask him about Ricky’s punctuality at the Madrid, and they don’t have any complaints. Ricky’s been very serious, attending his classes. And you know how conscientious Pablo is when it comes to his homework, how responsible he always is. El Bigotes has only come by one day to tutor them. He was away for a week and didn’t give any notice, and yesterday he told Ricky he wasn’t going to come by, and he didn’t. Gabriel goes with me to many places. We’ve had some adventures in the car you would really need to see to believe. The other night we went to the drive-in, and at the exit, with my God-given sense of direction, I started driving towards Querétaro. And it was when I was going by I don’t know what city that I decided to stop and ask for directions, and I returned to Mexico City. Each outing grants a surprise, and I never know whether my destination will be the coast or the altiplano.

Ricky has written you. Pablo hasn’t had time, and Gabriel’s typed a series of random letters on the typewriter. The boys miss you very much, and they really want to know what it’s like there. Gabriel thinks that you’re spending your time hunting with a rifle. Speaking of which, Willie hasn’t shown any signs of life. I'll call him next week.

The day after you left, your cousin Julio sent me four dozen red roses with a very affectionate greeting. I think I’ll need to thank him, but the days go by, and I don’t do anything. If he wants to have a private conversation, I’ll grant it to him, and God will be his witness.

I’ve been feeling very well, and when I feel poorly, I know that I can take a Valium, and life will become rosy once again. I’ve scarcely seen anybody, but the people I have seen, I’ve done so willingly. Nobody’s given me a hard time, nobody’s repeated any gossip, nothing. I believe that I’ve begun to exercise the art of personal defense.

Mi vida, enjoy your stay. Write to us when you can, we would like it very much. In my next letter, I’ll send you photos of all the little monsters in the pool and the two dogs and Don Pedro, who I believe you must miss very intensely.

I went to a movie with Raúl, who’s very low. Emilio Carballido came by, also very depressed, and Laura Mues, as hysterical as can be. Norma Castro invited me to lunch, but I made up some excuse. I’m not interested in seeing her.

I send you many kisses. If there’s anything I can do for you, please let me know, and don’t worry about us who, despite missing you “spiritually,” are doing very well, and please don’t worry that you’ve left anything pending. (I haven’t forgotten about Dr. Theodor. I’ll call her today.)

Rosario