Often dubbed a “writer’s writer” by the literary critics, Salter’s oeuvre spans seven novels, a memoir, several story collections, and even screenplays. His career saw decades of stylistic refinement and reinvention, from his first novel The Hunters (1956) to his final novel All That Is (2013). But two novels stand out as the apex of his literary career: Salter’s controversial 1967 masterpiece, A Sport and a Pastime, and his 1975 masterpiece, Light Years. A Sport and a Pastime evokes the decadence and nihilism of Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, but takes the Parisian setting into a far more mature, cerebral, and sexually explicit direction, depicting a city whose erstwhile splendor is still recovering from the ravages of war. Salter’s unnamed protagonist confesses, “It seems I am seeing everything more clearly. The details of a whole world are being opened to me.” Salter’s literary output championed the external world, both as the bustle of the cosmopolitan lifestyle, but also as an exposé of human longing as told through deceptively simple prose.

Light Years demonstrates a greater literary range than its more minimalist predecessor, the nearly surgical precision of Salter’s lines allowing the reader to more readily bask in the sensory immediacy of detailed scenes (though of course his trademark short sentences are still there to draw us back from these digressions). The genius of Salter’s work can be seen as the inverse of “depth”—his novels eschew the literary conventions of explicit interiority. Salter only allowed readers to skim the surfaces of his characters; even in A Sport and a Pastime, which is written in an unreliable first person, this attention to exteriority is manifest as a type of third-wheel voyeurism of the main characters’ sexual explorations. We as readers come to know Salter’s characters by what they do, not what they say or think.

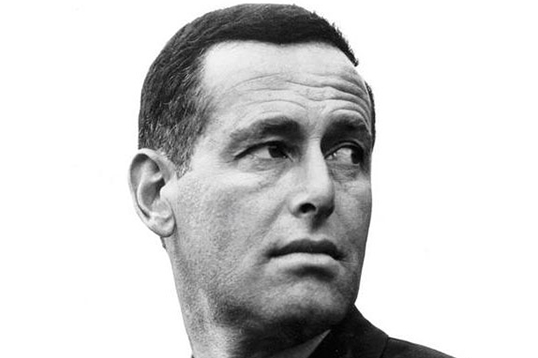

James Salter was born James Arnold Horowitz on June 10, 1925 in Passaic, New Jersey. He grew up in Manhattan and attended Horace Mann School in the Bronx; following his father’s footsteps, he then attended West Point. He joined the U.S. Air Force and served as a fighter pilot, flying over a hundred combat missions before stepping away from active duty to focus on his writing (at around this time, he legally changed his name to his pen name “Salter”). Channeling influences such as Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and André Gide, as well as his globetrotting military career, Salter’s major works are characterized by straightforward sentences, exacting prose, frank sexuality, and richly detailed global settings.

In the following interview, Chilean writer, critic, and translator Antonio Díaz Oliva converses with James Salter at Sofitel in Lafayette Square, Washington D.C. Their meeting (facilitated in part by Salter’s wife, the author and playwright Kay Eldredge) took place the second weekend of November 2014, weeks after their first meeting at the F. Scott Fitzgerald Literary Festival, where Salter had received that year’s Scott Fitzgerald Award. What follows is an intimate retrospective of a writer’s extraordinary life, a discussion of Salter’s final novel, and an exclusive final word with one of the most distinguished novelists of twentieth century American literature.

Do you remember the first time you read Francis Scott Fitzgerald?

Well, I was probably . . . I’m going to say it was 1946, but who knows the exact date. It was early. I don’t remember when The Crack-Up came out. That was an early book of him that I read and also his short stories. So, it was early on when I read him.

What about where you grew up? Was literature part of your world?

My father was essentially a businessman. He was in economics and real estate consulting. So there were no books in his life. My mother read popular literature, but I don’t remember her saying, “I’m reading a wonderful book.” And if she did, I can’t think about what such a book that’d be. It’d be a 1938 popular book. Probably the author and the title would mean nothing right now. I can’t say I had any literary influences in my life any other than from school.

You started to read literature in school while living in New York. Is that right?

Not really. Because my school was a day school, and we lived in New York, in Manhattan, and the school was about a forty-five-minute trip, up to Riverdale . . . well you have to know Manhattan.

Upper Manhattan?

Beyond.

Harlem?

Beyond, beyond. You had a long trip each way and those trips were devoted to doing homework on the way up or talking about what happened in school. I don’t remember anything literary . . . or the possibility for that. The friends that I had . . . you know, I had boyhood friends who talked about what kids talk about. I think the first time I started reading more was in college. I went to the military academy, which means that reading was not encouraged. But I had a couple of classmates who did read and who recommended certain books to me. Beyond that, I just instructed myself.

What books and authors were you reading back then?

That would be hard to say. I’m not going to give you obscure titles. I did read Fitzgerald, of course. I did read Thomas Wolfe, three or four of his novels. I read some English writers. Poets. I would say the regular schoolboy poets. And such. I would say it wasn’t a discriminating list.

Were you trying to write in those days?

I’ve written poetry in school. That’s something I did with a couple of friends who were on the train everyday with me. And I also had some poetry printed in a magazine which at that time—I don’t know if still exists—was the central poetry magazine. But I didn’t write a story or anything until the last year of college. It was the same situation I find myself every time I start something new. I didn’t know how to write a story. I did know how to tell a story because you tell stories all the time. It is a fundamental attribute of most people. Maybe boring stories, but they are stories. “This is what happened to me,” “You won’t believe this,” so and so. Those are essentially stories. But you have to put them in a more appealing form, more than a helter-skelter. It’s easy to talk and everybody is born with the ability to eventually talk and listen. Well, most people. So it’s easy to talk but it’s difficult to write. You have to conquer that difficulty somehow. That’s what I was doing when you asked about my beginnings. The process of doing that. I underwent that just as anybody else. You’re lucky if you begin a little early, but I wouldn’t complain or anything.

In an interview, you mentioned you resigned from the military in 1957, after being a pilot in the Air Force. You said that it felt like starting a second act in your life.

You could say that. I was somebody. I had a persona. From all those years of being in the army or preparing yourself to be in the army, and then in the Air Force, you travel and intersect with certain people and that was one the best things that happened to me. Eventually, I got into fighters. Here I was with an even smaller group of people. Some thousands. I don’t know the number, maybe three thousand or four, spread out everywhere, myself among them. But you are serving with some of them and so you become somebody. You have responsibilities. I’m sure it’s the same if you work in merchandising and you give up all that abruptly. From being in merchandising you go to North Dakota and try to grow a strange kind of vegetable. It is that kind of change. Everything is different. You don’t know anybody. You might regret it, or at least think about the choice you’ve made. I’m giving a silly comparison here, but it was actually leaving behind who you are to start again to become whatever you wanted to be. In my case, becoming a writer.

In the interview, you said that the day you resigned from the military you watched the city lights and wondered about this new chapter in which you would try to become a writer.

Yes, that’s exactly what I was talking about. I was in an apartment here in D.C. at Connecticut Avenue, as a matter of fact. I don’t remember where I was watching. Just the city lights. There was a feeling that I was abandoning my capital, my country. My life. My destiny.

Reading that moment in the interview I thought about Fitzgerald and his saying that there are no second acts in American lives . . . I think that idea is somehow relatable to your stories and even to your own career as a writer. You write about characters that struggle during the second act of their lives, that never forget about the first act.

I don’t know what Fitzgerald meant with that. I really don’t know. I assume he meant that an American story is a flare-up, and then burns out and there’s nothing much after. That doesn’t seem particularly profound to me. So, I know why he said that, but I have never put much attention on it . . . can you tell what it means?

That line comes from a very self-conscious essay. Fitzgerald was writing about himself. Then he died very young.

Of course, he didn’t expect to die. Or at least I don’t think he did. Although he wasn’t well, and he was demoralized and, as it happens sometimes, everything good in terms of his books happened after he died. Unfortunately.

Speaking about the “American story” as a flare-up, in your work there are a lot of images about lights and fires. Even in the titles: Light Years, Dusk, Burning the Days, and so on.

Must be important. [Salter smiles.] I don’t have a theme. Even if you pay a lot of attention to it, you are not aware of certain things that you are writing because they are integral to you. I remember an editor of mine sending me back a manuscript, a book of mine, and he said, “You realize there are fifty-two mentions of the word blue? I think you should look at them, there are too many.” Of course, I was unaware of those fifty-two words! It must be the same with light in my work. Light is fundamental in both a physical way and a psychological way. Mythical way. I’m glad to hear that you see in my books more light than darkness.

I wonder if when you started writing you were focused more on the plot than on the musicality of the sentences.

At the beginning I was writing for clarity and occasionally for images. The book that changed the way I write was A Sport and a Pastime. With that one I felt more assurance in the way I was writing and how it was written. Perhaps I was paying more attention to sentences rather than the overall story, plot, and narrative. But the change was not abrupt in any case. I think any writer faces the question about sensitivity, of what the sentence should be. Certain people have more sensitivity to music, others to painting. For example, I’m reading Under the Volcano right now. You know this book?

Yes, it is a very good book. Kind of messy, though.

Indeed. So, I tried to read it over like twenty-five or thirty years and I kept putting it down because I couldn’t become interested. For some reason I picked it up here, in Charlottesville, after reading William H. Gass’s critique of it. And the critique is terrific. The book was enhanced by that. I said to myself, “I’m going to try once more.” I have to say it is an amazingly good book and brilliantly written. Here I am, a writer myself, and for years I couldn’t read that book. It’s the same book, but something is a little different in me. Something changed or evolved. I think this goes on with your own writing as well. In a sense you are always changing a bit. But you know, I’m not changing for the better now. Generally, you think you are getting better to a certain point, and then perhaps maintaining that level, and then one day you realize that you are not going to do this anymore.

Have you revisited your first books?

I occasionally go back, but I never read the whole thing. I had to read The Hunters for a PEN auction in New York. I think their original idea was to auction first novels with the annotations, but in most cases, it wasn’t the first novel, it was the most famous one. The novel that the writer was well known for. It was Portnoy’s Complaint and American Pastoral, they had DeLillo’s Underworld. Unfortunately, they picked The Hunters, which is my first book. I said, “Well, alright.” But they wanted it annotated so I read it, and that was one of the few occasions I’ve done that.

How was it? Did you feel that the James Salter who wrote it was different from your present self?

No, no, I recognized myself immediately in the book. I recognized things like when a painter looks at a picture of his work. I had similar feelings. I’d say that the narrative was better than any subsequent narrative. But the writing was not. Too bad they didn’t go together.

After the military you moved to Paris. And back then Paris was the place where people went to become writers. Was Paris always a city you knew you would live in?

Certainly. I remember reading Saint-Exupéry in school, and we read it in French, so it didn’t mean much to me, except looking words up in the dictionary. But I knew he was a much admired figure. I think it was Wind, Sand and Stars. I think it came out before the war. When I said there weren’t books in the house, it’s not like there wasn’t a single one. We didn’t have a wall of books. Maybe a few books. I don’t remember reading Saint-Exupéry in my childhood, but later. So he contributed to my moving to Paris, I guess. Paris was emblematic in those years, for its style, for its clothing, luxury, because of French women. I remember the World’s Fair in 1939, in New York. The hardest thing was to get a table at the French restaurant in the French pavilion. We always went during the daytime to the fair, but we never ate there. That restaurant moved to New York and it was the best restaurant in New York. Everything French was very stylish, very glamourous. That was Paris of that time. Also, Hemingway. But it wasn’t about his books, it was about stories about him. The Sun Also Rises. I wanted to go there. I wanted to live that kind of life. And I finally had the chance to take a flight over there. And I saw what Hemingway and others saw.

Did it fulfill your expectations?

It was different. France was a mess by the time I got there. The bruises of the war were all over Paris. The depressed economy made Paris seem cheap, worn out, grimy. It was winter, so my first impressions of Paris were grandeur, but also not a very comfortable kind of life. Then, about four years later, it began to change, and after that Paris resumed itself. Now it has gone beyond itself. Many people love it, and so it has become not a playground, but something along those lines. I presume it was always a popular destination, although I suppose not many people could visit it before. It’s not like now when crowds arrive at cities like this, or Florence, Rome, etc., on a daily basis. You wouldn’t recognize them today, because that’s been the way since you were born. But did I find Paris as the legendary place that everyone talked about? Yes.

Between Solo Faces and All That Is there is a thirty-five-year gap Were you busy with different projects?

I was thinking of writing a novel, but other books came first. My memoir, Burning the Days, was written there. Two short story collections, as well. I simply didn’t get around to it; I had the idea of writing a novel, this novel. That was about thirty-five years ago. I made preliminary notes for it, but I didn’t like the characters. I felt that I made a mistake. The characters simply didn’t have the strength to carry me through, so I put them aside. And I reached the point, I’d say a decade ago, to think about it again. I worked earnestly for about five years before it got published.

And how was the process of writing All That Is?

You mean like if I had forgotten how to write a novel?

Yes. Was it difficult?

It wasn’t easy. Borges said very touchingly—I think he mentioned this in a lecture—that he never sat down and looked at a white piece of paper without feeling that he hadn’t done that before. That doesn’t mean it’s easy, but at least there’s a familiarity with the process. Once in a while someone gets hit by a falling star and the book just appears. And all you have to do is copy it down. So, I wouldn’t say this one was particularly difficult, it was not easier than any other book.

How would you describe Philip Bowman, the protagonist of All That Is?

I would say he’s a man who’s living what was thought of at the time as the golden age in America. And he’s unaware of that, as they all were then. This is a story that shows a more emotional than personal life. And like any life, it has people in it who seemed important, at the moment, or for a period of time, and then that importance either elapses or vanishes. Certain figures stay on; others disappear. I would say that at the end, he doesn’t lose the idea that there is still life ahead.

Do you like Bowman? Would you have coffee or a beer with him?

Oh, more than coffee. I want to be his friend!

Were you happy with the book’s reception?

I think the critics were . . . How can I put this? I thought I was fortunate in the coverage. The first thing that happened was a phone call from a woman from Texas. She was reviewing or covering the book for Publishers Weekly. She introduced herself and she said something like, “Philip Bowman knows absolutely nothing about women.” It wasn’t exactly like that. I mean, she said it better than that. It doesn’t surprise me. What she meant was that he was an outdated attitude, that he represents a démodé thinking.

Do you agree with what she says?

He’s definitely not a modern person. He is not a cutting-edge figure. When we last see him, he must be sixty years old, I don’t know exactly. Well, let me see . . . [Counts with his fingers.] Yes, he’s more than sixty. At the beginning, he’s living in an earlier time and he’s more representative of those times than of today’s.

I feel that All That Is ends with a mystery.

What is the mystery?

Bowman. He is the mystery. Even though I have been with him all his life, I have read extensively about him, he’s still a mystery to readers.

Yes, yes.

I wonder if that was one of the ideas of the novel: the impossibility of getting to know someone.

Yes, although he’s not intentionally mysterious. All I can say is that I wanted the end to be like, “Ok. Let’s leave it there.”

Do you think this novel has brought new readers to your work? Not only here in the United States but also in Spain and South America.

Yes, especially in places like Spain. What I think happened is that two or three Spaniard writers, and not in consort, but randomly, discovered a book or two of mine, independently, and they have written about it. That must have done something. I don’t know which book was the one that started all that. I’m inclined to say that it was Light Years. But I don’t remember the sequence of how my books were published in Spain. And I have earlier editions in Spanish. One in Buenos Aires. And then Salamandra began publishing the stories and novels. Then All That Is happened. I don’t remember the sequence. I’m conscious that I have readers in Spanish.

Right now, I’m reading a UK version of your Collected Stories. In the prologue John Banville compares your stories to the TV show Mad Men. Have you seen it?

I have watched just a couple of episodes. Of course, it is the same era. But Mad Men seems a little vulgar for me. But I can accept that.

What about contemporary fiction? Do you read any?

Not really. Well, I read Jennifer Egan’s novel, because it won the National Book Award. I know the names. I started reading Karen Russell, the book about the motorcycle. It is brilliantly written. So many books I’d like to read, and time’s scarce. The book that I choose has to be well praised. Name somebody and I’ll tell you if I have read him or her.

Jonathan Franzen?

I read some pages of him. I’m not really a fan. I’d be a fool to talk about him. I like Michael Chabon. I like his vitality and his attitude. But I haven’t read enough Chabon to really talk about him.

Is there anything you regret from your literary career?

I don’t like to say that I regret something. I’d like to have some parts of it back. I could use the time. There’s no point in regretting.

Is there any similarity between writing and flying?

People ask me that, but I don’t see the connection. Having been asked that same question a number of times, and thinking about it, I can say that flying has perhaps influenced my writing in a way that I don’t clearly see myself. It probably gives you a different sense of scale—of the physical world, of distances and time, of accessibility. Of certain useless things, like heaven and the skies. These things exist for everybody, but in a different way as when you are flying. I don’t write with that in mind. As I say, perhaps that has been the result of flying. That I write unaware of a different sense of scale. But I don’t always notice it.

What kind of your writer did you want to become during your formative years?

I wanted to be in a class where writers I knew were regarded seriously at the time, like Thomas Wolfe and all his contemporaries. Every writer we have mentioned so far. I don’t know how to categorize them. Serious is a funny word to use. We are talking about writers that are great writers because maybe at the surface it seemed that they didn’t do more than entertain you. But then you realize, in that entertainment there are things that go deeper than mere entertainment. I really can’t define it properly here. I wanted to be in that certain area of writers that rise above the rest.

How did you come with the title for this novel?

All That Is? I thought about it and it seemed the right title.

To me it sounds like an ending. Like someone gasping final words.

It can be taken like that. It can be taken in a finalist way, in a more embracing way, something like “Everything that is”. Yes. The original title was Torah.

I’m sure your editor didn’t like it.

No. The publisher said, “You can’t make it ‘Torah.’ Nobody will know what it is.”

And?

Well, I accepted that. And All That Is was the closest to the original idea . . . The idea of a final gasp. Not a bad title, anyway. What do you think?