We Computers is narrated—is authored—by a fictional AI called “We Computers”, trained on ghazals, an ancient genre of love poetry from Central Asia. This unreliable collective narrator weaves a solipsistic tale about its creator, Jon-Perse, a French poet and psychologist. In the AI’s telling, Jon-Perse’s life unfolds in multiple versions, increasingly shaped by the patterns, symbols, and thematic repetitions of the ghazals it has been fed. The novel explores what artificial intelligence is, what it might be capable of, and where its limits lie. At the same time, it is a love letter to the Uzbek language and to the region’s literary traditions, and a meditation on literature itself: can AI produce something genuinely beautiful? Can it be trusted? Does it matter who our author truly is?

Ismailov’s work has always been deeply rooted in Central Asia: in Sufi traditions, regional storytelling practices, and the intertwined cultural histories of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and the post-Soviet and Persian worlds. His fiction consistently reveals a region and culture that remains little visited or understood by Anglophone readers. Just as Jon-Perse is introduced to the ghazals of 14th century Persian poet Hafez by his friend Abdulhamid Ismail (AI, for short—is he ever real?) in the translation of We Computers, Ismailov leads his Anglophone readers to unfamiliar literary and cultural landscapes, while simultaneously confirming their significance through his decision to write in Uzbek.

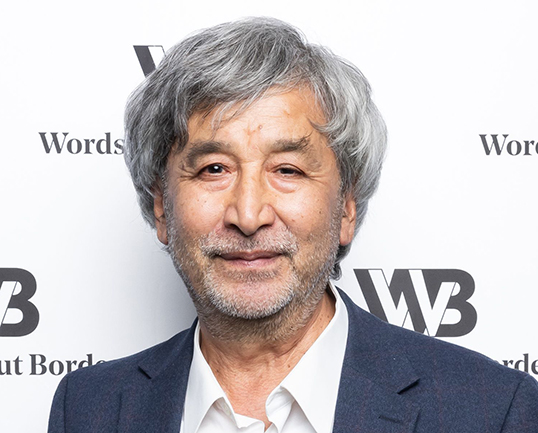

Ismailov’s choice to write in Uzbek is all the more important given that his work remains banned in Uzbekistan. Born in 1954 in Kyrgyzstan and raised in Uzbekistan, Ismailov was forced to leave the country in 1992 after the authorities accused him of harbouring “unacceptable democratic tendencies”. Ismailov’s subsequent prominence in global literature only undermines the Uzbek government’s power. His novels preserve and reassert a literature under pressure, bringing attention to the culture and politics of the region as they circulate globally through translation. As Ismailov explains in our interview, writing in Uzbek has never been more important, and digital technologies now make it increasingly possible (though, as he tells us, never simple) to reach readers inside the country.

Ismailov’s novels explore the liminality of exile and celebrate the rich and varied cultures that inform his life experience. Of Strangers and Bees (tr. Shelley Fairweather-Vega; Tilted Axis Press, 2019) ruminates on exile and displacement, focussing on tenth-century Islamic philosopher and physician Avicenna; The Devils’ Dance (tr. Donald Rayfield; Tilted Axis Press, 2017) tells of Uzbek author Adbulla Qodiriy’s arrest and execution in the 1930s—to survive he focuses on his own book about the Uzbek poet Oyxon and her persecution 200 years before (the novel won the EBRD prize in 2019). The Railway (tr. Robert Chandler; Harvill Secker, 2006) follows the lives of disparate characters passing through a fictitious railway station in rural Uzbekistan; A Poet and Bin Laden (tr. Andrew Bromfield; Glagoslav, 2012) examines the rise of radical Islam in Central Asia after the collapse of the Soviet Union; The Dead Lake (tr. Andrew Bromfield; Peirene Press, 2014) is concerned with the environmental destruction caused by Soviet nuclear testing in Kazakhstan; Gaia, Queen of Ants (tr. Shelley Fairweather-Vega; Syracuse University Press, 2020) examines themes of corruption and the émigré experience. Perhaps closest to We Computers, Manaschi (tr. Donald Rayfield; Tilted Axis Press, 2021) focuses on its protagonist Bekesh, who believes that he is fated to become a Manaschi—an important cultural figure who recites manas, epically long Kyrgyz folk tales.

I was thrilled that Ismailov could spare the time to talk about his work. We discussed artificial intelligence (an unavoidable topic given We Computers), how AI has been imagined in the past and how it is perceived today. Ismailov also spoke about the power of writing in Uzbek, the central role of translators, and the ethics of literary mediation. I was delighted to find that some of his answers took the form of poetry—something I hope future interviewees choose to emulate. In a twist worthy of We Computers, Ismailov even consulted AI for its opinion on his AI-centred book. Why not, after all, let it speak for itself? What follows, then, is an intertextual, multi-voiced conversation—a reflection of Ismailov’s rich life and literary practice.

—Sarah Gear, Assistant Interview Editor

We Computers is described as a “Ghazal Novel”. Why did you choose this form? How does it reflect the novel’s themes? Why did you turn to the poetry of Hafez in particular?

The ghazal is a universal love song, expressing both the human-to-human and the human-to-God relationship. Its focal point is precisely this ambiguity, which is akin to the medieval concept of sfumato in Renaissance art—a way of “living within a paradox”. Today, discoveries in quantum physics have shown us just how profound this worldview is. One need only recall Schrödinger’s cat, the ongoing debate about whether we inhabit reality or simulation, or the hype surrounding AI as a possible counterpart to the human mind.

Hafez was perhaps the most mysterious of the ghazal poets. Every line he wrote is layered with mystery and paradox, which is why, to this day, people in Iran and Central Asia still use his ghazals as a form of fortune-telling.

My heart was a treasury of mysteries, but the hand of destiny

Closed its door and handed the key to the tormenter of my heart.

Or:

That person belongs to the people of clairvoyance, who understand hints;

There are so many subtleties—where is the keeper of secrets?

Certain images recur throughout the novel—tulips and the moon, for example. What is the significance of these images—for your Uzbek readers, and for your international audience?

Recurring themes take the form of recurring symbols in Sufi ghazal poetry. Tulips, for example, symbolize the ever-present mystery of life and of poetry itself. For Uzbek or Persian readers, these symbols require no explanation. For Western readers, however, Shelley Fairweather-Vega has done an excellent job of providing contextual notes where needed, allowing the symbols to resonate fully in English as well.

In fact, Western poetry also uses the same symbols. A notable Western parallel can be found in Emily Dickinson’s poetry, where the moon often symbolizes mystery, distance, or quiet authority. In her poem “The Moon was but a Chin of Gold,” she writes:

The Moon was but a Chin of Gold

A Night or two ago—

And now she turns Her perfect Face

Upon the World below.

That is so beautiful—thank you! There is a striking symmetry between the novel’s initial online publication and Jon-Perse disseminating his work by email. Was this parallel intentional from the outset?

No, there was no deliberate sense of risk in that choice. In fact, Jon-Perse distributes his novel by email for aesthetic and literary reasons—or even for philosophical considerations related to AI. In my case, however, the decision was purely pragmatic: it was simply a way to reach readers directly. But thank you for spotting this interesting parallel, because in other instances I have used those kinds of parallels deliberately.

There was no overarching aesthetic or metaphysical intention behind it, nor any attempt to blur the boundaries between what happens in the book and in my own creative life.

You’ve said you were working on the novel long before the current boom in AI. If you were writing We Computers today (even just a few years later!), with AI far more advanced and integrated into daily life, would you change anything? Do you think readers now interpret the book differently than they did when it was published on Telegram in 2022?

I was fortunate to befriend people who are now considered among the founding figures of generative literature and generative poetry. We were discussing questions of AI and literature many years—indeed, decades—ago.

Recently, I recovered books that I had parted with thirty or forty years ago, finally receiving them back from Central Asia. As I began sorting through them, I discovered many works on artificial intelligence from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. I have been fascinated to read them again, because they posed the great metaphysical and philosophical questions about AI and the human mind.

Today, by contrast, we tend to focus much more on the minutiae of AI rather than on those larger questions—questions that preoccupied writers like Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, the Strugatsky brothers, and many others of that earlier generation.

Rediscovering these books has been deeply rewarding. In that sense, the core elements are still very much present: artificial intelligence, poetry, and human life. They remain essentially the same. Nothing fundamental has changed in these elements or in their relationships to one another. For that reason, I would not change anything—those relationships still resonate exactly as they did before.

What is the contrast between how AI was imagined by these authors in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, and how it is treated today? What can we learn from writers like Asimov and Bradbury? And in turn, what would you like readers today to learn from your novel?

As the Russian poet Sergei Esenin said, “Big things are best seen from a distance”. When Asimov or Bradbury were writing about AI in the 1970s and ’80s, they had the distance needed to observe it as clearly as possible for their time. Their work focused not only on the technology itself, but also on the human dimensions of our relationship with AI—our ethics, values, and moral responsibility.

Today, these questions have shifted toward more pragmatic concerns. Yet what we can still learn from Asimov and Bradbury are the moral imperatives that should be built into AI. As a tool, AI is fundamentally neutral; however, because it is created and used by humans, our ethics and moral standards inevitably apply to it as well. As for myself and my book, I’m humble enough not to claim that I can teach something, therefore I have asked ChatGPT that question. Here’s what the AI says about We Computers: “The author would like readers to take away a deeper awareness of their shared responsibility in shaping the future of AI. We Computers is not about technology alone—it is about the human choices behind it. The author hopes readers reflect on how curiosity, ambition, fear, and empathy influence the tools they create, and understand that ethical progress must keep pace with technical innovation. Ultimately, the novel invites readers to see AI not as an external force acting upon humanity, but as a mirror of who we are and what values they choose to uphold.”

Jon-Perse believes it is possible to “reconstitute a person’s very existence from their words.” Do you think this is true of your own work?

In my case, there is no need to reconstitute anything—it is already there. The process of writing is one of self-discovery through language. As I said, a writer serves the language, but at the same time serves his own inner world through that language. He finds himself within language and through language. In that sense, everything I have created is, in one way or another, a reflection of my inner world.

With age, I have become even more solipsistic in my focus. Over the last year, I have written two novels that are deeply centred on myself. One tells the story of the very first novel I read, when I was six or seven years old, secretly taking a book from my mother’s shelf. The entire novel is devoted to that formative reading experience—what it did to my mind and the consequences it had for the rest of my life.

The second novel focuses on my own unfinished work—the projects I used to begin and never complete in my youth—and on my later discovery of the logic behind that pattern. Once again, it is an exploration of my inner world.

In that sense, yes—what Jon-Perse says in this book applies to me completely.

We Computers are at once divine, omnipresent, but also naive, and ultimately constrained by Jon-Perse’s inputs. They are also unsettlingly close to sentient. How are we to understand them?

I think it is too early for us to part ways with artificial intelligence—to separate ourselves from it and grant it a kind of autonomy. After all, AI is a product of the human mind. It may represent the ultimate expression of just one facet of our thinking: rational, logical, linear reasoning. Yet it is still entirely a human creation. As such, it reflects the strengths and limitations of our understanding of the world, including our understanding as expressed through language.

In this sense, AI remains fundamentally human in origin. Perhaps in my work I made computers appear more humane than they truly are. I may have attributed to them emotions, intuition, or even mysticism—qualities they do not genuinely possess, even if they sometimes seem to simulate them convincingly. Their ability to imitate these traits is part of their nature.

Perhaps the best way to understand AI, then, is to recognize that it is ultimately our creation—a mirror of ourselves rather than something separate from us.

Since We Computers can only work with the material they are given, what does the novel suggest about authorship and control? It feels as though We Computers are the ultimate unreliable narrator. Are we supposed to distrust the narrative—and is this a comment about AI as a whole?

Can I answer this question by a poem?

Yes please!

Standing by the fire that has burned itself out at night,

and remembering that night—I seem here like a passerby,

a kind of homeless wanderer—

morning-faced, creased like rough linen . . .

For some reason the word “merchandise”

has blackened like a final ember and,

in the brightened world, closed its eyes.

I think to myself: even if we believe

that thought burns of its own accord,

is not the fortune of each thought bound

to whether there is a hollow within us—

a space waiting for it—or not?

In truth, we do not fill the world with the thoughts inside us,

but heap the ruins—

the ruins within—with the trash of the world.

I imagine: those who lingered close to the fire, to the flame,

their eyes full of tears,

their faces red in the night,

splitting like overripe apples beneath a summer sky,

losing all sense of time, spilling down to earth,

covering the ground—oh God!—

as if swarming toward my mind, my hollowed mind,

ready to set it alight.

The night has scattered its ashes.

In a cradle a child awakes.

Hell is switched off.

Dawn startles—as though it had sucked deeply,

again and again, from the breast of night—

and consciousness shivers into being . . .

Thank you! I would like to ask—who is the ideal reader for We Computers—your Uzbek readers, your friend who inspired Jon-Perse, or an imagined global reader?

No language belongs to any one person; languages belong to everyone who speaks them. Since I write in a particular language—this book, for example, was written in Uzbek—anyone who speaks Uzbek, wants to speak Uzbek, or is learning Uzbek can be its potential reader, indeed its ideal reader.

Because the book has been beautifully translated into English by Shelley Fairweather Vega, it now belongs to English as well. And as it is translated into other languages—Turkish, Persian, Italian, Czech, and others—it will likewise belong to the readers of those languages.

In this sense, an ideal reader is simply anyone who wants to read the book, including AI itself.

Did the fact that your work cannot be published in Uzbekistan, and often reaches readers via translation, influence your approach to We Computers, or indeed, your work in general? Do you feel you were writing for translation to some extent?

No, no, no! No, I am absolutely not writing for the sake of being translated into other languages. If I decided to write in English, I would simply write a book in English myself, which I have done several times, in fact. The more I think about what it means to be a writer, the more I come to the conclusion that a writer serves the language, not a readership or any particular group, unless one is producing something specific, like a manifesto.

Literature itself serves language. It takes a language to places it has never been before. It challenges its limits, renews it, and enriches it. Therefore, my task as a writer is to develop and give new life to the Uzbek literary language. The space that existed before me will continue to exist after me, but during my lifetime I leave my own mark on the language as a writer who belongs to it.

In that sense, no—I never think about making life easier for translators or anyone else. I challenge the language to its very limits.

But there are wonderful publishers, such as Yale University Press, that define their mission as bridging languages and cultures. They share works written in Uzbek, Ukrainian, Chinese, French, and other languages with English-speaking readers. The same credit is due to translators such as Shelley Fairweather-Vega.

How has the rise of digital platforms—Telegram, messaging apps, online publishing—changed your experience as a writer in exile? Has this expanded or shifted your sense of audience?

It has certainly given me, and people like me, a powerful tool to overcome censorship. I can now publish my work directly on digital platforms and reach readers immediately. At the same time, there are many uncontrollable aspects to this process. People can do whatever they want with your text: alter it, reuse it, redistribute it in various digital forms. It becomes a messy situation.

This happened in particular with The Devils’ Dance. At one point, during a political transition—when one president had died and the new one had not yet been installed—individuals printed the online version of the book and began selling physical copies without any contracts, consent, or even my knowledge. In circumstances like these, the work starts to resemble folklore more than something protected by authorship and copyright. [It led to] a major controversy: a heated debate erupted between two groups of Uzbek women, resulting in nearly 500 posts exchanged back and forth.

You first shared We Computers on Telegram for your Uzbek readers. Are you able to gauge how it was received? And how does that reception compare with responses in the US and UK?

I decided to share We Computers on Telegram deliberately. When I shared The Devils’ Dance on Facebook and it went viral, it led to many consequences. This time, I wanted to avoid causing trouble for my readers—or drawing them into confrontations—especially since the theme is again quite controversial. For that reason, I chose to publish on Telegram with comments and feedback disabled.

The only indication I had of reader interest was the number of views, which reached into the thousands. That is all I know about the readership of this work in Uzbek.

As for the difference in how the book has been received in Uzbek versus in the English-reading world, its English-language release has coincided with the current hype around AI. In the Uzbek context, what interested me most was not AI itself but poetry—the counterpoint between artificial intelligence and poetry. My memory is that readers focused much more on the poetic aspect then.

By contrast, the reviews coming in now, especially from English-language readers, concentrate primarily on AI and the questions it raises about human creativity. That, to me, is the biggest difference in reception.

Shelley Fairweather-Vega has described We Computers as one of the most challenging books she has translated. How did the two of you collaborate on such a complex and multilayered text?

I’ll tell you something that may sound counterintuitive: I would never translate my own work. I would never become a translator for Ismailov, so to speak, in order to avoid torturing myself by the means of language :) . Perhaps that’s why I have never translated myself from one language to another. As I said earlier, I am focused on challenging a language—or a particular sphere or state of that language—to its fullest extent for a specific purpose.

But there is a category of people “to whose madness of bravery we sing hymns”, as one writer put it. These are the translators who take on the challenge of challenging the challenge itself. Shelley is one of them. Because I admire that audacity, I am always curious and eager to understand how they accomplish it. Obviously I’m always there to ‘serve Virgil’ in the hellish lows or heavenly heights :) of my catacombs, yet I believe the translator’s task is ultimately their own: to attempt the same feat in another language.

I am eternally grateful to all my translators, including Shelley, who has translated five of my books. I will never tire of admiring their ‘madness of bravery’ and dedication.

You once compared language to atomic energy—powerful and potentially destructive. Do you see language used, and “created,” by AI as having the potential to negatively affect language and literature?

In one of my youthful, angry, revolutionary poems, I dismissed poetry altogether, suggesting that it could be replaced by a concrete mixer filled with a dictionary—all the words thrown in together—because it would produce the same effect. In a way, AI is now doing something similar. It is a combinatorial tool that mixes words from a dictionary according to different paradigms, algorithms, and patterns of usage or frequency.

Ultimately, it performs a kind of “concrete-mixer” function. Sometimes this process can yield completely unexpected results. At the same time, some argue that AI merely serves already digested material, since it is trained on an existing body of work and therefore only reorganizes that material into new combinations rather than creating something truly original.

There are different views on AI’s creative potential in language. I remain fairly neutral. It can produce interesting linguistic results, but it can also generate language that is perfectly grammatical yet deeply uncreative—smooth, correct, and utterly commonplace.

What can readers, translators, and publishers do to support greater visibility for Central Asian literature today? Who should we be translating and reading now?

We have only a handful of translators working from Central Asian languages, including Uzbek, and Shelley is by far the most prolific among them. Today, with many writers seeking to find their voices or claim their place on the global stage, there is a strong desire to be translated into English and reach an international readership. Shelley, like other translators of Central Asian literature, is in high demand.

We are not spoiled for choice when it comes to translators, which makes us all the more grateful to those who bring Central Asian literature to the attention of the world. I am especially grateful to Shelley, who has translated not just one but several of my books. Some of these have yet to be published, awaiting the right time, but her work ensures they will eventually reach readers.

Shelley is a true missionary for literature, dedicated not only to my work but also to that of other writers, including female authors like Shahzada Samarkandi and Kazakh writers such as Zaure Bateva, among many others. This year, she also translated Castigation by the Kyrgyz author Sultan Raev. There are also translations of the Uzbek and Central Asian classic novelists: Abdulla Qodiriy, Cholpan, Chingiz Aytmatov, O’tkir Hashimov, Erkin A’zam, and others to mention just a few. The more she and others translate, the more Central Asian writers’ names will appear on the global literary map.