It is fun to watch their hands during this YouTube interview, as they gesture ‘writing’ as if with a pen, indicating a now superseded practice, but one they nonetheless continue to practise as they discuss the daily ritual of diary writing, something that makes Latour assert that his published works are only ‘0.01%’ of his output. The writing is the thinking and there is no thinking without writing, which, he insists, is an extension of the battle to erase the form/content divide: the subject matter at hand invites a reconsideration of style and form. If there is no stylistic shift, there has probably not been any thought, because one has stayed within the ‘usual styles of philosophy or the social sciences’. Aramis was thus ‘a novel’, and the new book, Where am I?, the publication of which provides the occasion for this discussion, draws on the ‘mythic’ potential of Kafka, while also engaging in thought experiments as community discussions, following the pragmatic model of the ‘ledgers of complaints’ previously developed.

Despite Latour’s modest disclaimers, Coccia is entirely aware of how Latour, as a writer, has engineered a revolutionary way of seeing the world by ‘recognizing the agencies of all that is non-human’ and finding ways to bring out a plurality of ontologies, to be sensitive to their precarious existences, this sensitivity being the very definition of an expanded aesthetic. This is the Latourian challenge that has engaged so many readers, commentators, and critics. Given the existential threat that is the new climatic regime, how are we to respond? What kinds of subjectivities have to be forged, human or non-human, that can respond? What new aesthetic forms have to be invented? These are some of the many questions that this discussion engages with as it elaborates upon the necessary links between writerly practice, research methods, pedagogy, and public performance, the multiple fronts needed to describe what is happening around us, not ‘on the planet’, but in all these ‘critical zones’.

After introducing Bruno Latour, Emanuele Coccia invited him to talk about a collection written during his time at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice.

I thought that since I was coming to the Maison de la Poésie, I should at least bring a little snippet of poetry. It is in honour of Pasquale Gagliardi and it is called ‘At the Foot of the Extinct Volcano’. It is in a Cavafy kind of style.

At the foot of Vesuvius

The archaeologist wonders to himself

If he too

Would have escaped in time

Like those painters surprised

By the blazing cloud

In the house on the Via dell’Abbondanza

Their fresco half-finished, still wet.

It was he who extracted from the cold ashes

Their skins, brushes, compasses, and mitts

Such that he could deduce from their frozen gestures

That there were three painters—or maybe four.

In their haste, one of them even spilt

A full pail of white plaster

On the still-wet face of an ochre-coloured Diana.

Then he raises his head a little and asks himself

Which door he would have run to

If he should have to leave his brushes and scrapers,

His notebooks and laser pointer

To escape this river of lava

broaching Mount Vesuvius.

The volcano groaning now with towns and steamships, factories, buses, and ships

In this other innocent, indifferent burning cloud

Indefatigably blanketing the bay

‘The most beautiful bay in the world’

With its layers of burning ashes.

So maybe he should decide to remain,

Like them,

Leaving for unlikely future digs

the task of filling the shape of his body

With plaster, the emptied form of a scientist, moulded in black dust?Pliny the Elder, he read, made fun of the priests

Who thought they could calm Vesuvius

With a sacrifice to Vulcan

Instead of stoically rejoicing

In the forces of nature

Finally unleashed against the imperial Roman fleet.

But the archaeologist on a miserable salary

Looks around

For some pristine bull

He might sacrifice

To stop, for a moment, the rain of pumice stone

Light and burning, empty and careless,

That covers the land, like the sea

With a heavy superficiality

And bring us back in the end to ‘just the forces of nature’.

He sighs and lies down on his stomach again

To extract the precious pigments.

‘There must have been four of them, yes,

One of them a rather clumsy apprentice

Who had the job of daubing the grotesques’.

Thanks so much. I’d say it is a poem somewhere between Cavafy and Lucretius. On the topic of poetry, have you always been a reader of poetry, or is it a recent thing, and what is the writing from which you emerge?

I’m not a reader of poetry at all, dare I say, not even an amateur. For me there is no one better than Cavafy. I also like poets who are completely out of fashion, like Saint-John Perse. And I don’t put anyone above [Charles] Péguy, as a poet.

Yes, in fact I wanted to begin with Saint-John Perse and Péguy, the subject of your first main text, your doctoral thesis, a dialogue between exegesis and ontology. One of the things you keep showing and coming back to, in the end, is the extent to which everything is a question of exegesis, of the reinterpretation of a text which is there, and which we didn’t know how to read or . . . how should I put it . . . fully understand.

What really interested me with Péguy, from a very young age, was in fact the way he modified the tone of the writing, along with the perennial question of why Péguy is repetitive. It’s true, he repeats, (laughs) we can’t deny that. This is something, by the way, that also really interested Deleuze in Difference and Repetition.

At the same time, this formal invention is a very profound philosophical invention, since as a follower of Bergson, and a none-too-orthodox Christian, he tries to bring back the ontologies that belong to the religious and national beings he is speaking of. He does it with a formal invention that people found very troubling at the time. When the Cahiers de la Quinzaine arrived in the post, with, I don’t know (laughs), the five thousand sonnets, I mean quatrains, of Eve, many people must have been shocked! It’s often said that people simply slipped it under the table (laughs). But by the same token, this repetition is precisely a part of what has always interested me, that is, how does a formal repetition allow us to capture beings that are otherwise inaccessible?

So, in the end, this capacity to grasp the emergence of beings on the basis of signs of a formal nature is something that you have often applied in your analyses, in particular in the book on [Louis] Pasteur. One of the exercises you carry out in this text is to show the extent to which Pasteur was not discovering something—an object, a reality—that didn’t exist before; he was instead recognizing an agency—a presence, a capacity for action of a being—that had always been there, but not admitted into the circles of those who . . . how shall I say . . . constitute a society.

We can then see to what extent everything goes through an analysis of writing, what was in fact at the time a science of writing, semiotics, in other words. You show how everything necessarily hinges on the textual presentation of these germs and recognize a subjectivity in the way in which they are represented, the way they are spoken about.

At the time I was being trained, in the sixties and seventies, the linguistic turn was happening. At the height of this moment that was Derrida, Barthes, etc., I simply settled on a more positive, rather than negative, spin. Constructivist, rather than deconstructivist chuckles), if I can put it like that, an extended version. Yet it is complicated to understand the links between exegesis and ontology in Pasteur; you are right to mention that. There is a certain type of being, referential beings, that are constructed in the laboratory, that also depend on interpretation. But here we have to add all the texts involved, the texts on which other scientists are working, commenting on. These texts are so extraordinarily important and difficult to grasp, these texts are produced during experimentation by witnesses that are in some measure voluntary or involuntary, and they take the form of what I might call inscriptions.

I have made extensive use of all sorts of genres, some of which can no longer be found. Like François Dagognet, [I am] deeply interested in the materiality of transcription in the broadest sense of the term. Anthropologists like [Jack] Goody, [contribute to] a whole literature on the nature of transcription, which, in fact, continued my interest in the form through which ontology reveals itself, rather than if one moves out from language in order to capture something that, clearly, has no meaning. But that doesn’t make me a writer. I am not . . . I have an enormous admiration for writers because they manage to capture things that I have only touched on in my meanderings through the usual styles of philosophy or social sciences.

This is why I work a lot with my friend Richard Powers, who I consider a great American novelist. We got to know each other because I was writing Aramis, which was a little literary in my kind of way (laughs), at the same time as he was writing his extraordinary Galatea 2.0, and we swapped books, noting that we were doing something similar. Obviously, he had the capacity to construct characters, build up scenes, and find tropes that allowed him to bring to light that extraordinary situation that we call ‘artificial intelligence’. This was not on the same scale as what I was able to do with my slightly distorted social science, if you like. So, I have always inscribed the question of writing, or form. I have always tried, even in this new book, to change the form of the book, but that doesn’t turn me into a writer. A poet, even less.

You are being too modest, in my opinion. What is very interesting for me, coming back to the question of Pasteur, germs, and scientific laboratories that you evoke . . . this first book was really quite stunning. It is a book which recognizes the centrality of writing in the work of someone who is not supposed to be a writer. If I can summarize (and correct me if I’m wrong), this is a book that really upset the Academy at the time, especially because it is one of those books that established a new way of analysing science and technology, but above all because it had an extremely revolutionary idea. In the end you apply the science that is normally applied to so-called ‘other’ cultures. You are working with a very reflexive method. You apply it to the culture to which the anthropologist or anthropology belongs, that is, modern culture, and to its quintessential modernist expression, that is, science itself.

To put it a little crudely, it is anthropology applied to laboratories, that is, looking at scientists as if they were ‘primitives’. This reflexive turn produced a surprising effect, very surprising. Firstly, because it would lead later to your book, We Have Never Been Modern, which asserts that science only repeats the idea that there is a distinction between subject/object, between persons and things, but that it never stops making things speak. In a laboratory there are humans who are always giving voice to inanimate objects—which brings me back to the question of writing. This is something of great importance. You show the extent to which the work of inscription and translation are necessary in order for science to be possible, and how the actual scientific field is an immense site of translation, inscription, and circulation of writing. You say ‘I am not a writer; I am not a poet’ but you have this capacity to see this writing that no-one wanted to see. It is like the letter hidden in plain sight that had never been pointed out.

It’s one of the classical definitions of poetry, to dive, for possibly naive reasons, right into the form, to always be attentive to the form out of which the depth emerges. As it happens, in the sciences, it is little used because the sciences were thought to be in an abstract situation in people’s heads, without any form to speak of. This is what allowed for the anthropology of sciences to first of all relocate them, as it were, quite simply: ‘Where are they, what are they doing, how much are they being paid, etc.?’ And secondly, and this is where semiotics was useful, re-attribute to so-called inert characters the power to act, something to which semiotics is very attentive and for which it has a very useful metalanguage. The school of thought doesn’t matter that much, [Charles Sanders] Pierce, Umberto Eco, or [Algirdas] Greimas (for me it was Greimas). What is important is the capacity to speak for those who look inert, like this table, giving them the capacity to act . . . which also actually occurs—a particularly amazing feature, which I have shown across numerous studies—in scientific articles.

One just has to read scientific studies to notice that as soon as they are perceived within the exegetical grid, as it were, there is a proliferation of agencies, powers to act, that this extraordinarily dramatic object, is very clearly the focus of the articles. Because that is what ‘making a discovery’ means (laughs). So, it wasn’t very complicated. And Laboratory Life was one among a number of works where I used a literary trope, I must admit very heavy-handedly, which is to treat objects like ‘primitive’ peoples, primitives who have stopped being primitives at the same time as we turned out never to have been modern! It is a way of speaking, a literary genre in the same vein as The Politics of Nature, in which I played around with a rough style, without beauty, but with a stylistic approach. And Aramis was a novel. I try every time to find a form, a literary genre that corresponds to the subject matter. When I wrote Rejoicing, which was about religious beings, it wouldn’t have made any sense to talk in a social scientific manner. It was the experience of religious beings that interested me. This was more in a . . . how can I put this . . . narrative, subjective genre. You have to adjust yourself to the situation every time. In fact, every time, I use tricks (laughs) . . . but poetry and literature are way up there above me, along with music. One has to know one’s place.

Quite. But coming back to this . . . this sort of mixture, this hybridization that you practise for each of your works, in writing . . . the book on Pasteur, with its ‘germs at war and in peace’ [the subtitle of the French edition] obviously has a strong reference to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and you transform what should have been a quite literal relation to scientific discovery into an epic tale, a war between different sectors of society, where clearly not all are human. There is that aspect, and then what also comes out strongly in this book (as in other books of yours) is a metaphor: a theatrical metaphor. You describe the science itself as a theatrical fact. But to stay with this hybridisation that you practise in each of your works, I am just a little curious in a kind of literary–culinary way. Does it impose itself or emerge in the course of working? For example, with your new book . . . this mixture . . . this coup de théâtre, that allows you to write on Kafka, but also allows you to present yourself as a new Gregor Samsa . . . did this idea come to you straight away?

I was enchanted by Kafka, an author whom I don’t particularly like. It was a totally unexpected enchantment. Let’s not forget that although reading is a habit that bourgeois children no longer possess, my generation had it. Now it’s the internet and everything. Sartre describes it very well in The Words. At that time, we bourgeois children (although some were older than me) were born in diaries. This means that my published works are 0.01 per cent of what I have written. In fact, they are derived from things I have written starting at thirteen years old. I have emerged from a writing practice much older than myself. Such people probably no longer exist. This is an interesting literary epoch to pursue, children who are made by . . . how can I put this? (laughs) Sartre puts it well; they emerge from the fact that they write. So, I don’t make much of a distinction between the flow of action (chuckles) . . . how does James Joyce put it? The stream of consciousness and writing.

So, you have a practice of writing every day in your diary?

Since I was thirteen.

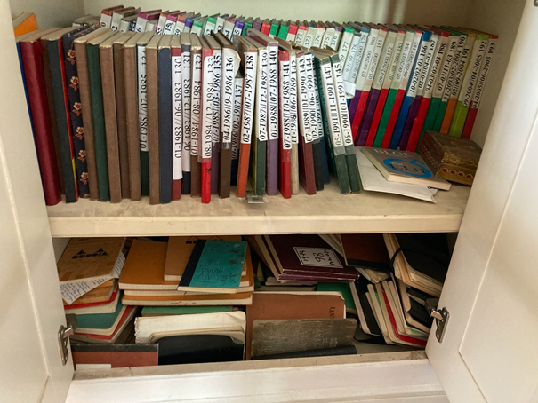

You have notebooks?

Yes, 223 notebooks (they laugh).

What a great editing job that would be!

In the beginning, when you are thirteen, they are juvenilia. You are thinking because you are writing, and the writing makes you think. So, I never had a problem about whether I was a writer or not. Writing makes one think, because you write stupid things. On the next page, something happens, and on the next. It comes out of this weird thing (laughs) that I have a lot of trouble teaching my students when I do thesis writing workshops: ‘If you don’t write you aren’t thinking.’ I think it is something to do with the times we are in. Now, writing in order to think, is much harder. But the advantage is that one doesn’t imagine one can think without writing. If there is some kind of relationship with poetry, it is the idea that there is nothing outside of form. Which is the case with ‘philosophical’ literature, which is not the style I find myself using, but there is still philosophical writing, which is a writing completely in its form. It’s where it is born. The idea that there are philosophers, analytical for example, who think they are writing ‘properly’! ‘Proper language’, that has always given me a good laugh. Not only that, I was a reader of Nietzsche. When I did philosophy, I was inoculated by Péguy, but I was also inoculated by Nietzsche. Then I was re-inoculated by semiotics, then again by ethnomethodology, which is not known for its literary qualities, but for its attention to detail. Then ethnography/ethnology. All these are ways of making oneself attentive to the fact that the important things, let’s say ontologies, are contained within, do not escape, their formal networks.

The 223 notebooks. Photo by Bruno Latour

So that is why when people say to me it is strange that you are writing plays, putting on a play or writing a philosophical text on the same subject, say Gaia, there is a clear continuity for me. The audiences are just different. You are addressing different people, with different effects. But they are the same beings; they can’t get away. Philosophy is not—this is my (laughs) my doctrine: philosophy is not a metalanguage. It is a language, like any other. There is an easy transition: theatre, poetry (I make no claim there), exhibitions—very interesting because that’s another genre, completely different, in spaces, with people moving around. Between that and a text, I have constantly sought the balance between writing and exhibiting, as I did with You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet. There are good effects, other effects, other audiences, but there is continuity, because every time it is the form that holds the revelation of the ontology. That is why, when I came to read my first thesis again after fifty years, I said to myself (laughs), now isn’t that strange, it is called Exégèse et ontologie! In the end, I have done nothing but that!

You brought up the question of theatre. You make a point of ‘continuity’, the stream of consciousness, which is also the daily writing of a journal, but there is also an element of discontinuity: that is, how do you deal with what is still a formal expression with a different materiality, how do you manage to pass from verbal writing to a spatial, more expository, kind of writing?

That is very straightforward, because it is the strangeness of these beings that engages us; their ecological mutation, to put it simply, becomes palpable. This is what Amitav Ghosh describes in The Great Derangement, that is, he has a novel, tornadoes arrive, what can be done? The medium is here, while the event is there, and they don’t correspond at all. So as soon as I got involved in this issue (I had the good luck to meet Frédérique Aït Touati, my daughter working in the theatre), I said to myself: these things are too big, intimate, powerful, painful, for the style (I forget, it has been some time), which is still too impoverished, shall we say, so here we have to tame these beings. We are dealing with problems of survival. We have to find ways of grasping these things, as Amitav Ghosh says, in their dimensionality (laughs).

It’s right, what he says about the novel being a problem of individuality. When there are collectives, the novel has an air of the fabulous, or the mythic. So, it is exactly for that reason that Gregor Samsa comes into my story. It was impossible to speak of these things with a being who was, shall we say, an ecological activist in a demonstration experiencing trauma. You need a mythic dimension. After all, we are returning to generalities. You know better than I do that it is the redirection to mythical beings who are more capable. Let’s say that this false realism that is the human subject in the midst of society—in short, this whole vocabulary that we can see doesn’t work at all for our times. So, I have no trouble creating an exhibition, two exhibitions, doing theatrical work, etc., but when I get on the stage myself, it’s a disaster, giving real theatrical people a good laugh because it was such a flop. But when they picked it up to make theatre it was fine. But that’s vocations. Even for exhibitions, when I was motivating people, commissioning them; actually curating an exhibition is a vocation. But I basically know where to draw the line. I had the opportunity to work with Frédérique, and we get on well because I know just when to stop, when she is right. And at the same time, I’m useful because I . . . because when I try to speak in my language, it is not a metalanguage, it does not weigh down on what she is doing. So that is how I have worked collaboratively with numerous visual, plastic artists, like Tomás Saraceno. It is not the usual position of the philosophical way of talking: you do the practice and I do the theory. Theory is a language like any other, a form. And it can have deformations that can be useful if they create resonances with the plastic arts. Sometimes the artistic work gels; sometimes my form is better (laughs)—it depends on the case.

You spoke of Tomás Saraceno, who is exhibiting with Sarah Sze at the moment at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain.

Yes. I think this is a great collaboration, because for me, her work—unfortunately invisible—Sarah Sze says things in her language that are infinitely deeper—or at least more ‘up to the point’—than I could ever say, in any case I resonate with her. This is a principle I learnt, by the way, from Michel Serres. What he really developed was—when he spoke, not always when he wrote—was that the arts are always their own metalanguage. There is no metalanguage superior to the arts they are interpreting. This is one of Serres’ great principles that I always greatly admired.

You speak of this idea that philosophy is not a metalanguage, and what I find is a really significant, really—I was going to say ‘revolutionary’— principle, is that it is through writing that things have to take form, show themselves. All problems, limits, become formal or literary or stylistic problems. And so, in this way you transform an aporia, an impossibility, into an invitation to change the writing, the style, or the register. Or, as you say, associate oneself with someone with a better practice or a different kind of agility associated with another writing form, whether it is writing through visual arts, the theatre, exhibitions, etc.

Not so long ago, I was at the Nanterre-Amandiers Theatre with the great dancer [Stéfany] Ganachaud. That was my first idea of Gaia, from that dance! When she dances through geo-history . . . I met her at the exit from one of her sensational performances and I buttonholed her and said (laughs), excuse me, young lady, I absolutely have to have you do a very precise set of steps for me, moving while fleeing. And that was the first idea, long before I wrote the Facing Gaia book. You have to pass from the one to the other, and, in the opposite direction, that is why my sole contribution to poetry, if I may say, the most useful, is to have run thesis workshops for twenty years. With doctoral students who were lost because they were told to do a social scientific thesis, but they were not told how to write it. There was no thesis writing workshop. They were told to have an idea, but it isn’t about ideas. They should describe what they have at hand. And I offered a whole series of methods that I had made up over the years, that saved a certain number of these lost students (laughs). I told them: your problems are necessarily writing problems, and if you can’t solve them through writing, then dance them. Get up! Invent movements, find a way . . . because transforming the problem that you have is not a theoretical problem, it is a writing problem. And the writing strategy is the subject of the workshop. And it was wonderful. I never had such a great pleasure; I never held a research seminar, even on my own stuff, but I always ran thesis writing seminars. Even on subjects where I was not on the committee for the students. Just on the writing.

What has been very empowering is to demonstrate how the ecological question (you cited Ghosh’s The Great Derangement)— and well before that, with your Politics of Nature book, that ecology itself, or the ecological crisis—is, among other things or perhaps above all, an aporia in writing: particularly in the words we use, like ‘nature’, etc. And I think this is one of the strongest arguments in the book that preceded Où suis-je—that is, Down to Earth. Ecology is a problem of writing because it is founded on the incapacity to describe the space where we are living—the Earth—and to write the space we inhabit. In the book, you invite us to repeat the (ancient and modern) exercise of the ledger of complaints, that is, begin to describe—to write—the spaces we live in, and to begin by writing down the beings we are attached to. From this point of view, ecology is a poetry manqué, an incapacity to have grasped to what extent space, the Earth, Gaia, has become more and more distant in our everyday writing.

We are on the same track. It is the same problem for a generation of authors and thinkers, the huge gap between the affects and aesthetics associated with ecology, and it’s enough to make you die of boredom . . . if this is what they want to defend as a planet, this big blue ball, it is lamentable! It’s a real problem. I didn’t know Ghosh’s book; I read it recently, avidly, because it is just the subject I was seeking—an aesthetic.

I have a number of options to get out of this situation, but one of them is very affecting to undertake since the participants are neither artists nor intellectuals nor academics: auto-description exercises.

Can you tell us about the workshops?

They consist of auto-description workshops in French villages and towns, that I have written about in Où suis-je, that have the great advantage of not being part of that political indignation that is addressed to . . . we don’t know exactly to whom. They describe their survival conditions, which has significant therapeutic effects, because they are dominated or limited in some way, but once they start to describe what they depend on, they are recentred, because even if they don’t describe everything, an enquiry has begun, as it were.

But the other thing that is tied in is an experience of form; there is a whole group of people—not just me, musicians, theatre folk—who try to work through what happens when one starts to describe one’s conditions of existence, without blowing one’s top (laughs). That’s the problem. So, clearly, collectively, there are arguments that start right away, as soon as one starts in on animals, the internet, access to medicine, in short, exactly what didn’t happen with the yellow vests: giving back the capacities for articulation (not a bad definition of poetry, by the way), and a capacity to articulate situations.

We have invented devices to bring out emotions: for example, a guy tries to describe how he is saving his farm by improving his methods for (efficiently) raising animals; there are vegetarians who are furious, etc. One can go straight from there to a political discussion of a ‘classical’ sort. So here we are inventing forms that have the effect . . . this same farmer, once he has defined his world, as it were . . . those who respond do so in four different affective tonalities: fear, joy, sadness, or anger. That changes everything, because in a few seconds they go from ‘I’m very angry about what you said,’ to ‘I’m delighted by what you just said.’ Emotions are reworked and rearticulated, and that really has metamorphosing effects, which are fascinating to follow. I’m interested because you can’t get through, leap over, this trial, this stage, of political ecology, so to speak, because one’s not going to save the Earth with all these technologies, if one doesn’t do this work which is clearly completely grassroots, and which is also that of the ledgers of complaints, sitting down again in a territory which is obviously under attack, threatened, destroyed, half-ruined, but which is where one is; one is not somewhere else. This relocalizing work (laughs), in Où suis-je, seems very important to me.

And it is very touching to hear that, in the end, you can describe this experience you are speaking of as an invitation, even a re-education in that diary-writing practice that you spoke of earlier.

No, not unrelated, it’s true.

. . . and which you said was now gone.

I hadn’t thought of that (laughs) . . .

It is as if you invited them to begin a diary that is no longer a bourgeois kind of diary because it is not written on one’s own, but in a community. And what is also brilliant about what you have done over forty years, one of the founding intuitions of your work, is recognizing the agencies of all that is non-human, whether it is an object, a machine, or even and especially animals, plants, and the Earth. It is as if the exercise you are speaking about were a diary in which the protagonists are others . . .

Except there is no longer any composing . . .

What do you mean?

Your daughter is a little young, but my grandchildren are going through school, up the grades, and they are still not doing any writing. Instead, they are asked to have ideas. No one says, “Describe this glass for me.” I used to spend days describing a bouquet of flowers, gladioli, whatever. Writing is what people, kids, have to be taught. That’s where they begin to have the capacity to pay attention, to look for the right words. You realise that you don’t have the words, that the thing you are describing is inert, then you animate it. In short, description is the basic vocation for writing. And if you do it every day, I’m not saying you have to write every day . . . this narration, this requirement to narrate, it’s that which gives you a way to write.

The word ‘description’ seems weak, and people think it is simple, but there is nothing more difficult than description (laughs). People always want to explain. The principle behind the writing workshop is the same as the one behind actor-networks, which is my little sociological theory: if you have a need to explain, it means you haven’t adequately described. Once you have described it, the explanation becomes superficial.

That’s why Tolstoy, at the end of War and Peace, writes a text—not all that interesting—wherein the Holy Ghost leads Russia against the atheist French, which is really not up to his usual standard. Here the description is sensational, but the theorization is more banal, if you like. It is a general problem, managing to find a way to write, for the social sciences (for the pure sciences, there are other ways, to do with laboratory inscriptions), a description so advanced that the explanation is superficial.

On that point there is another question. Amitav Ghosh’s book The Great Derangement pointed to the limits of the novel, as a register. He said that the bourgeois novel, the modern novel, is incapable of coming to terms with the climatic upheaval, for a whole range of reasons, among others, the metaphysical image of a world which is inspired by a probabilistic realism that projects onto nature an endless repetition of the same, which makes nature less worthy of description, because in the end everything is repeated at once. And on the other hand, human psychology is foregrounded where nothing is repeated. That’s kind of how he analysed it. So, in the end he calls for a change of form, of style, a sideways step like you spoke of before.

But you are indicating a more serious problem: this absence, this incapacity, this neglect of composition in writing. Where is that coming from? Is this a culture we are losing or a laziness? Why are we so little invested in description?

I have no idea about French teaching and why it has deteriorated to this point. Or why the necessity has gone . . . I have no idea why it has been abandoned. But it can be done in a way which is not necessarily in writing. One can ask for a narration, for example. I think a lot of teachers do it, of course. It is like learning the piano where you have to practise every day. This writing practice still goes on . . . I don’t teach doctoral students any more, but those who are working in the field have to write about what is going on, all the time. Those writing on archives, they already have written texts, but us ethnologists have to produce texts that others comment upon. So, if you are not in the habit of composing texts, for your dissertation . . . there is always this tendency to want to say what you are thinking. But you don’t think unless you write. First you have to describe, then you can think. This necessity for composition.

If I had my grandchildren, I would make them—if I followed my own advice, which is very unlikely (laughs)—write a composition every day, like we used to do when I was a kid. This is what makes you want to . . . it especially makes you see how little and how badly one describes the things one is not attending to. They obviously get to read Victor Hugo, etc., but that is not the same thing as when you try to do it yourself and regularly confront the fact that what you are saying is terrifyingly banal. That’s where diaries have an advantage. When you do it for, what? Sixty-five years (chuckles) and you notice that what you are saying is idiotic, and that you can say it a little differently, and it slowly gets better. Imagine . . . imagine how you get an added value of . . . of the point! At my age, if I don’t write every day I feel as if my day is wasted and I’m becoming a vegetable.

I’m a diary writer too, so I share your vision. But there is something very interesting in what you are saying, because on the one hand you speak of a supposedly disappearing bourgeois culture, but there is also an element emerging from the way you describe composition and description which is a sort of ethnographic culture of fieldwork writing, but which deviates. What I find very interesting is that it is as if you had deviated from a practice which was related, for example, to exploration, to conquest, the need to describe something far away, that doesn’t belong to us . . . something very different because in the end you don’t need to travel because we have never seen what is right under our noses.

The lyrical aspect of the writing is sublime, as is the exercise of the ledgers of complaints, as well as your exploration of emplacement, such that we have never really looked at or seen the world around us. And from this position we can see to what extent the planet has changed. It is as if you invited us . . . and I find this very beautiful . . . you invited humanity on Earth today to take up a kind of Adam and Eve position again. You know there is a very nice piece by Mark Twain, I don’t know if you know it, very funny and very well-written, the private diaries of Adam and Eve. It is sublime, and one of the most touching aspects of these two texts is they have to figure out what kind of feelings they might have looking onto the world for the first time, and the embarrassment in baptizing, naming things, anything, not immediately present to them. It is as if in this exercise of description, you are asking us to think once again like Adam and Eve, who have to baptize a world that has just been born, or born again because of climate change and a radical change of the planet which demands a new description, don’t you think?

We are being born, again, into a world which is rather different. And we were driven out of the old one (and I must absolutely read the diaries you mention). There is something specific about description which is that it is the taking up again of description that counts. Here exegesis is obviously useful, all these forms of repetition that capture something. This is what we are doing with the ledgers of complaints. The first things said are banal and not very interesting. There is always this effect, when it is a collective exercise, the description of one person’s troubles is refined, one notices that . . . if you stopped eating meat then . . . that guy over there with his magnificent cows, what will become of him . . . the countryside would change. In short, this knot, through the operation of redescription, becomes finer. This is where one gains, once again, this capacity for attention and articulation. All this is to be capable of articulating the relations we entertain (chuckles) with the beings of the world at a time of the new climatic regime, as I call it, where we are stripped of the capacity to describe, because we are not where we thought we were, not in the epoch we thought we were in; we are not the beings we thought we were. It is a disorientation that is colossal!

And so, the idea that we can redeploy the little vocabulary that ordinary sociology gives us for our usual struggles to understand the fact that we are not in the right place, we are not in the right epoch, and we are not the people we thought we were, it is not really very likely. It is for this reason that the arts in general—poetry, visual arts, theatre, cinema—become so essential in this period. Without them we are trying, with a false realism—that is what ordinary sociology has become—to try to capture (laughs) all these transformations, and, clearly, it is impossible.

What you say is very interesting. When you say the arts are important, what you are suggesting is not just an exercise in attention, but also the translation of this attention into a form that can be shared. So, what is important in literature, whether it is diaries, visual arts, cinema, or writing ledgers of complaints, is that one becomes sensitive to these beings, but one is obliged to translate these sensitivities or sensations into something shareable that circulates. And the other interesting thing you brought up that should have a little more elaboration is the point about repetition. You said a moment ago that it is less the composition itself than the fact it is taken up again and repeated. This struck me, because we were speaking about exegesis, the technical term for Christian hermeneutic practice, in other words the endless exercise of rereading a text that remains the same over the centuries. But also rewriting in fact, because what is surprising also is what the Catholic Church did in Europe: it forced a whole continent to rewrite the same history—just look at Rome—ten thousand times, by the coolest and most glamorous artists. Surprising that it went on for so long. There is a story, a new one, and the most modern, contemporary artists are asked not only to read and believe in it, but above all to rewrite this story in another fashion.

This is what Péguy was doing. It is what theology in general does. There is this extraordinary moment in the Gospels where Jesus arrives in Nazareth and opens the book of Isaiah where he reads, “The Messiah will arrive.” He sits down and says to the people, ‘Here it is; it is happening’ (laughs). If now a priest has to comment on this phrase, this event, he can comment on it by saying, ‘This event is happening now.’ But the problem is he could miss it! This is the whole problem with repetition and the whole problem Péguy has; one can miss it. When he comments on Clio’s wonderful text on Homer, one has the responsibility to weaken Homer as well as that of taking it one step further. This is the greatness of exegesis, and it is clearly a notion tied to the politics of a deeply Christian exegesis, but it is also more general, it is also, as you yourself have studied, a property of living things. It is a kind of repetitions, of stubbornness and transformation which is also very specific, while the model we have of duration is one where we have more trust in immobile things that persist in time. It is an opposition: what persists persists because it doesn’t persist.

And Péguy, who is completely associated with poetry, with narration, with repetition with ‘manducation’ (as [Marcel] Jousse put it, eating words while practicing them, which is essential). All that is ‘business as usual’, if I may, for exegesis. You have to repeat without missing. Between rehashing and repetition, there is this famous continual attention for discerning, which means one has the overwhelming responsibility, as Péguy tells us, not to weaken Homer.

And in the end it is the same responsibility in life, because, as you say, all living things, since their gestures are coded, are obliged to repeat otherwise this same myth, this same story, this same language.