I would like to walk with you, one spring day, with the sky brushed grey and last year’s old leaves still being dragged by the wind around the suburban streets; and I would like if it were a Sunday. In certain city quarters, melancholic and grand thoughts often arise; and in given hours, poetry wanders, marrying the hearts of those who love each other. Hopes are also born that cannot be expressed, favoured by the boundless horizons beyond the houses, by the fleeing trains, by the northern clouds. We will simply hold each other by the hand, and we will go with a light step, saying senseless, stupid, and beloved things. Until the lampposts are turned on and, from bleak housing blocks, there will emerge the sinister stories of the city, the adventures, the longed-for novels. And then, we will stay quiet, still holding each other by the hand, since our souls talk to each other without even saying a word. But you—I remember now—you never said to me senseless, stupid, and beloved things. Neither can you, then, love those Sundays that I mentioned, nor does your soul know how to talk to mine in silence, nor do you recognise, in exactly the right moment, the city’s spell, or the hopes that descend from the North. You prefer the lights, the crowds, the men that watch you, the streets where they say you can find fortune. You are different to me, and if you had come that day for a walk, you would have only complained about being tired; this and nothing more.

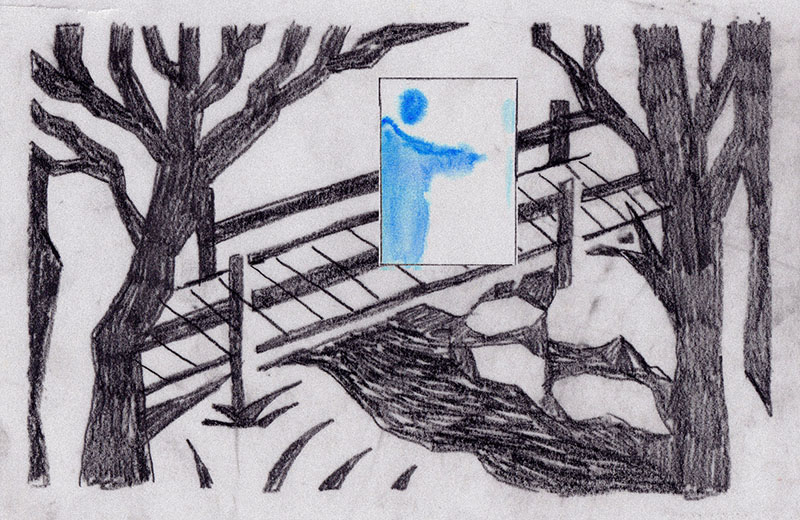

I would also like to go with you in the summer to a remote valley, where we would endlessly laugh about the simpler things, and I would like to search for the secrets of the forests, of the white streets and certain abandoned houses. To stop on the wooden bridge and watch the water pass, to listen to the telegraph poles, to that long story without an end that comes from up above the world and goes who knows where. And to tear flowers from the meadows, and here, supine on the grass in the silence of the sun, to contemplate the chasms of the sky and the little white clouds that pass, and the mountain peaks. You would say, “How beautiful!” Nothing else you would say because we would be happy, our bodies having lost the weight of years, our souls having become fresh, as if newly born.

But you—now that I think about it—I’m afraid you’d just look around you without really understanding. You’d stop, worried, to examine a sock, and then, you’d ask me for another cigarette, impatient to get back. And you wouldn’t say “How beautiful!” but other meagre things that don’t matter to me. Because, unfortunately, this is how you were made. And we wouldn’t be happy, not even for an instant.

I would also like—let me just say—I would also like, with your arm under my arm, to cross the wide streets of the city under a November sunset, when the sky is pure crystal. When the ghosts of life run atop the cupolas and brush past the miserable people at the bottom of street ditches that already overflow with agitations. When memories of blessed ages and new portents pass above the land, leaving behind them a kind of music. With the innocent arrogance of children, we will watch the faces of others, thousands and thousands of them, who flow past us in rivers. We will send out, without knowing it, light and joy, and all will be compelled to look at us; not out of envy or ill will, but rather, they would smile a little, with a feeling of kindness, thanks to the evening that heals the weaknesses of man. But you—I know well—instead of looking at the crystal sky and the airy colonnades beaten by the exceptional sun, you’ll want to stop and look in the windows at the gold jewellery, the riches, the silk, those base things. And you, therefore, won’t be aware of the ghosts, or the presentiments that pass, and nor will you feel, like me, called by proud fate. Nor would you hear that sort of music, nor would you understand why people look at us with kind eyes. You would think about your poor tomorrow, and above you in vain, the golden statues on the spires will lift their swords to the last rays of light. And I would be alone. And useless. Perhaps all of this is foolishness, and you are better than me, not expecting so much from life. Perhaps you are right, and it would be stupid to try. But at least, yes, this at least; I would like to see you again. Whatever happens, we will be together somehow, and we will find joy. It doesn’t matter if by day or night, summer or autumn, in an unknown town, in an unadorned house, in a run-down motel. For me, it will be enough to have you nearby. I won’t stay here—I promise—to listen to the mysterious creaking of the roof, nor will I watch the clouds, nor will I pay attention to the music or the wind. I will give up these useless things, things that I love even. I will be patient if you don’t understand what I tell you, if you talk about things that are strange to me, if you complain about old clothes and money. There will be no so-called poetry, no shared hopes, no sadness so friendly with love. But I will have you nearby. And we will manage, you’ll see, to be happy enough, very simply, just man and woman, as happens all over the world.

But you—now that I think about it—you’re too far away, hundreds and hundreds of kilometres that are difficult to cross. You are inside a life that I ignore, and other men are next to you, to whom you probably smile, like with me in days gone by. And it didn’t take much for you to forget me. Probably, you can no longer remember my name. I have by now left you, confused among countless shadows. And yet, I don’t know how to stop thinking about you, and I like telling you these things.