As soon as she woke that morning, she cleaned her bag of the candleholders and everything she had bought from the Buddhist supplies store the previous day. Over a camping stove she softened the butter she had bought especially from the small store on the street, and with the pads of her fingers smelling of tobacco rolled some cotton into a wick, then she struck a match and brought it toward the candle. But there was no picture of the departed behind the candle. No picture existed other than one showing them sitting on the barrier of a wooden bridge across a wide river. Visualizing what she could recall from the picture, she bowed three times to the candle she had just placed there. May his soul find peace, she thought, and quickly find its next rebirth. Remembering how her grandmother had said that, on the forty-ninth day, the soul would find its next rebirth, she thought, Today, you’ll find your way back to the earth. The soul must have sat on a cart. A cart is the warm womb of a woman. When the soul enters into the warm womb where the fetus is developing, the woman will feel a shock in her womb and tell her husband and the people nearby, “I felt the quickening! It moved for the first time!” They will all be happy at the sign that the soul has entered the womb and, one by one, they feel the pregnant woman’s belly. Imagining this in her mind, she presses against her own belly. She’s just woken up, and couldn’t spare time to make breakfast for herself. So, when she pressed against her starving, flat stomach, it was like she had put her palms on the wall of the bottomless darkness of limitless space. For a moment, she feels jealousy toward the unknown woman into whose womb her lover’s soul has entered and against which it is pushing as though announcing its arrival. She thinks, I have no luck to receive him as my child in his next life. If only I could have a baby with him, that would be another way to keep him on the earth, beside me. The last thought seems more practical. But she is a little too late for that.

She was not a religious person. And yet, on the forty-ninth day, having faithfully counted them out on her fingers, she awakened with a firm faith. She boiled rice and added raisins; she ate a few spoonfuls and left the house. She couldn’t participate in her lover’s funeral. She hadn’t known how to introduce herself to his mother, who sat among the ashes and dust of the tragic incident that had recently befallen her family. When the day of the funeral had come, his relatives had emerged from his apartment as dawn broke, carrying a large black coffin. This they had placed in the back of a long black vehicle, and they had sat in several cars, weeping and wailing, and had driven away in a funeral cortège. Secretly observing them from a corner of the nearby block, all she could see was their dark silhouettes. As they filed past, she leaned weeping against the cold wall and felt for the first time the darkness and chill of this world. Now the dark, cold world felt empty as well. When the sun, which had felt hot and shiny simply because he had existed in the world, shyly rose, she neither perceived its light, nor did she sense its warmth.

She hailed a taxi. An elderly driver came to a halt in an old car. The vehicle gave off a thick, musty version of the smell which hung around the tips of her fingers. “Gandan Monastery,” she said to the gray-haired driver and, without saying a word, the old man drove off, choosing the route by himself. If she had said the name of a newly constructed building, a modern shopping mall or a place to eat where youngsters might gather, he would have looked back at her with a tired gaze, as though seeking help, and repeatedly asked the address. Gandan is now one of those rare places in the city which this old man knows without any confusion. But for her, Gandan is basically a foreign place, perhaps one of the least-known areas of the city. But because she had been raised by an old mother who would sit and recite mantras as she wore away the beads of her rosary, she had learnt how to offer candles. If loss and grief should ever occur to her, she had gotten a vague indication from her grandmother that this would be the place to go. Recently, she had once more opened a chapter of the book of her life that she had closed upon turning thirteen, and had started to recall long-forgotten terms such as the forty-nine days, reincarnation, candles, prayers and, Gandan. When a sudden incident made her close another chapter of the book of her life, she needed to revive words from a chapter she had previously closed. When a person dies, a chapter is closed.

They stopped in front of Gandan. There, several hundred pigeons, flying overhead and coming down to land, welcomed her. Skirting these many faithful pigeons were a few old women selling rice. They seemed to be sitting there in a line like children who had given up trying to separate the flocks of sheep they were herding and, left with no choice, had gathered around the combined flock and were chatting away. “Buy some rice,” said one of them in a feeble voice, “feed the pigeons! Earn some merit!” For her, the old woman would be the one to earn the merit, since she had already brought rice to feed the pigeons. So why did this old woman want to offer her the merit that she herself would earn? Nevertheless, she bought rice from the old woman, and earned merit by feeding the pigeons and, as though in gratitude for receiving the merit, she placed some extra loose change in the old woman’s hand and entered through the main gate of Gandan monastery.

“Where are the prayers being recited?” she asked, and a young monk indicated an enclosure surrounded by a path for circumambulation along its thick mud wall. Inside, there were three separate Buddhist temples. At the entrance of the enclosure was a little yellow building for receiving prayer requests. Inside the building, on the other side of a wooden barrier, sat a line of monks, noting down the prayers to be said on behalf of the faithful, reckoning the combined fees for all the prayers, and giving receipts away. There was a board pinned on the wall next to the door that reminded her of the style menu on the wall of a hair salon. She wrote down a few prayers described on the board as “Prayers for future rebirths of the deceased,” then went over to one of the monks in red mantles who were sitting like bank tellers behind a wooden barrier with a glass screen. The money she offered to this fellow would pay for a service to be done somewhere in outer space to cause the door of Hell to shut against the soul of the deceased, and make the doors to Paradise open to it, or else help the suffering soul, lost in the outer realm, find its rebirth in the world and give it a chance to develop once again within a mother’s womb.

“I’d like to have some prayers recited,” she said. “The prayers for the dead, the Lhogotoi kunrig.”

“This is for the deceased’s merit in the next realm?”

“Yes.”

“You’ll need to add the Amitabha ritual then.”

“Ah, does it work differently from the Lhogotoi Kunrig?”

“The Amitabha ritual. That’s different from the Lhogotoi Kunrig.”

“Oh, OK then.”

She wondered why we communicated with the Buddha in a foreign language. We used to think of the language of those mountain people as the language of the Buddha, the language of Heaven that will welcome us in the next realm. That too was her inheritance from her grandmother. Until this point, she had thought it the language of the Buddha’s teaching, but she had not thought that it might be the language of the people who lived in the mountainous area that bordered the west of Mongolia, simple people in the regular world just like her own people. She was intrigued by what exactly the Tibetan term Lhogotoi kunrig might mean, if it were to be translated. If it needed to be translated in order to be understood, it could not be Buddha’s language. Buddha’s language cannot be enclosed by the box of phonology and words, and its meaning must reach simultaneously the depths of every soul, without any misunderstanding, without any discrimination. That’s what she was thinking. If Buddha’s language is comprehensible to everyone, then it should be comprehensible to her, too. The Buddha whispered into my ears using his own language so clearly, she thought, so, now I’m here. Thinking in this way, it seemed she shouldn’t deify the simple foreign words written on the sheet of paper she held as Buddha’s language or as an unknown, mysterious bridge between Buddha and herself.

As indicated by the monk who had written down the name of the text, she left the building and entered the middle of the three Buddhist temples. The faithful filed inside and sat here and there on the benches that ran along the eastern and western sides of the temple. The resident monks likewise entered in ones and twos and sat in two rows at the center of the temple, looking toward one another. She spent some time observing the interior, looking at the Buddha statues that lined the curved wall of the temple, all of them caked in many years of dust, and the devotional objects covered in the soot of the candles that had been lit and snuffed out many thousands of times. When she sighed, she breathed in the thick atmosphere of the monastery, the commingling of the all-pervading smell of the candles and the dust, and it was as though the constant sorrow of the years thickened like smoke in her chest. Suddenly, she wanted to go outside and smoke. Whenever something felt misty inside her, she would get a craving for cigarettes. The thought that the peculiar mist of ennui in her chest came from cigarettes lightened her mood.

Before the recitation started, she got up to go out for a smoke. At the door of the temple, she passed a monk holding a long white sheet of paper lengthwise, as though it was an offering scarf. Inscribed on this sheet of paper was a list of who had requested which prayers and in whose memory. The money she had paid was now ready to go out onto the path of magic. As soon as the chanting started, strengthened by the recitation of mantras, it would ride on the voice of the chanting monks, who sat in lines in the center of the temple, would fly beyond the boundaries of this world and into the atmosphere of the next world, passing directly through the gates of Heaven and Hell. The woman looked back at the monk, and through the open door of the temple it was quite clear that the monk she had passed was tearing off small pieces from the paper that he held out lengthwise and handing them to the monks. She wondered which monk the prayers she had written down might go to, but this was not a profound thought, and she slowly moved away from the door of the temple to find a secret spot where she could smoke.

But the purity of the monastery seemed superior to mundane thoughts. She hadn’t managed to find anywhere to smoke away from that holy place . Since she had gone outside anyway, wandering inside the enclosure like a thief and failing to find a smoking spot, she decided to circumambulate the three temples on the path along the enclosure, turning the prayer wheels as if expiating her dismissal of that holy place. As she turned them, it seemed that the words of the mantras carved on the prayer wheels peeled away one by one and flew in the air. There were pieces of paper, glued to the surface of some of the prayer wheels, on which people had written their deceased one’s name. Like the cuckoo lays its eggs in the nest of other birds, they counted on the prayers of others to mark out their deceased’s future path. Seeing the deceased ones’ names on the pieces of paper glued to the prayer wheels, the woman felt pity for herself. If she were to die right now, there would be nobody to clear the path for her and perform a ritual. She was an orphan. Her parents, who had left her in this world as an orphan, had not even blessed her with a sibling on whose shoulder she might lean during hard times. The only person she ever had was her grandmother. But her grandmother was also long gone. Afterward, the woman had thought she had met the man of her destiny, with whom she could share her orphaned solitude, but once again that person had died, and for forty-nine days she had offered candles for him, and now she was here at the monastery, turning prayer wheels. But if the roles had been reversed and the woman had died and the young man had remained, would the young man have turned prayer wheels and lit candles in offering for the woman? The woman was not certain that, within the young man, there would be such desire and deprivation as there was in her own heart.

Together they had experienced the excitements of youth, they had exhausted themselves laughing, they had cried and sulked, and sometimes they had fought and slammed doors; for many months one had chased after the other when the other had been running away. It would be more truthful to say that most of the time, it had been her running after him, and that the young man had gone missing. She hadn’t wanted to lose this one person who had come into her lonely life. But the life of the young man was full of other people. They were the same people who had come out of his apartment, in the break of the dawn, carrying his coffin, and had placed it on the back of a long black vehicle. They had sat in several cars, weeping and wailing, and had driven away in a funeral cortège. Those were the same people who had made the young man’s life impossible to live, holding all the space, sucking all the air from his room, cornering him from all sides and denying his existence at every second. When he felt his life overwhelmed by so many people, the young man would run away. The woman was sometimes one of these people. But the woman, siding with the young man, had mostly acted as a refuge, a final hope, a support, to which he could run. The woman knew that. Whenever she had become conscious of this, doubt would arise, and she would ask herself, Am I a refuge for him to escape from others? Am I nothing more than that? When she wanted to be at the funeral, and to stroke his cheek, and to see him for the final time, the doubt had hobbled her legs, and she had been unable to move. What kind of relationship, she would have said to his mourning mother, had she had with her son?

People are susceptible to the words of the dead. The living are so submissive to the dead, even about something that, if the deceased were alive, they would have argued and fought to the death about. Competing, fighting over something, sowing discouragement, and judging one another mercilessly are crucial ways by which the living feel themselves alive through engaging with others. Thus, loving, feeling the warmth of each other, and recognizing one another’s beauty are the same selfish needs of the living, in order to feel better about themselves through the acceptance of others. But what if one side suddenly quit this egoistic game of the living by stopping such feelings? If the other feels nothing but total numbness, then the game must end there. It means that one person has given up fulfilling the other’s selfish needs. This is the dead’s way of saying That’s enough. The one who gave up feeling anything first will decide the end of their relationship. And the living will be left with no choice but to follow the other's decision. Period.

When a period has been put at the end of the story, you cannot add your words to it; it’s pointless. It would be unfair to the dead if the living tried to provide a one-sided conclusion to their relationship by using their status as being left alive on the earth to attempt to expand the relationship by their own definition. If she visited his mother and said, “I was your son’s girlfriend (a lover, someone close to him),” that would be an attempt to put an ellipsis after the period. She didn’t dare ascribe to herself all the names that the deceased hadn’t given her while he was still alive. Such behavior is unfair, like going alone onto the wrestling field, wrestling against the air, and then raising a finger to indicate victory. He might have had reasons for not having brought her into his home and for not having introduced her to his mother, and his decisions must have been based upon reasons only he knew. For her, she had no choice but to respect and follow the deceased’s wishes. After all, she was one of the living, who should be susceptible to the words of the dead.

As she turned the prayer wheel in front of her, the name of an unknown deceased person that was written on a small piece of paper and stuck to the wheel spun with it so fast that it became a white line flashing before her eyes. Like the brilliance of the sun cutting through the darkness of the broad universe and hitting the earth, this continuous white line, revolving powerfully, shot up to the dark space above the earth, reached the deceased’s wandering soul, and became the cart on which to travel through the next realm. By turning the wheels, the woman had supplied mounts for the souls of the deceased, whose path through the world she had not intercepted while they were alive. She concluded her circumambulation, and again she walked towards the middle of the three temples. The recitation might be beginning.

When she got to the hall, she could clearly see through the open door that the monks had already sat down and had turned to the first pages of their texts, ready to begin. The faithful, who had been wandering around, standing together here and there, had sat down too. Some were fingering their rosaries, others had their hands joined in prayer, and some of the younger ones were just sitting there, their eyes watching with curiosity the inside of the temple. The woman was a little anxious that she was late, but the moment that she pulled herself together and stepped across the threshold of the temple, the air behind her blew fresh, and there came a sound like many pigeons flapping their wings. She looked back, and a young monk with a brisk step was coming toward her, throwing his mantle across his shoulders as he went past. But as soon as she saw the monk, who by now had taken a couple more steps, the woman stopped dead in her tracks. She stood quietly, holding her breath, her face pale and cold. The monk passed by, adjusting his mantle, indifferent to her staring eyes, and now he walked quickly to the end of the line of monks, sitting down cross-legged behind a low table. His eyes, his expression, his face, his body, his way of walking, and his character all called out inside the woman, He looks so similar! Her heart was thudding. She had barely crossed the threshold. She moved away and sat down on a bench not far from the door. All the while, she kept her gaze on the monk. She looked again, not trusting her eyes. Being so taken aback, she didn’t know what to do in that situation; all she could do was stare at the monk, absentmindedly. A person who had left this earth in an unfortunate incident forty-nine days before was now here, sitting before her, about to say prayers for his own movement along the path toward his next rebirth.

The two of them would occasionally play cards together, and he would sit cross-legged with his back quite straight and look thoughtfully at the cards in his hand, his eyebrows knitted, just as this monk was looking at the text in front of him. The monk glanced up from what he was reading and looked directly at the woman. Her eyes, unblinking, suddenly filled with tears. The young monk’s face didn’t change. He adjusted his seat and waited to begin the recitation. There was a strip of white paper in his left hand.

Though the woman had sometimes noticed the tall young man who went in and out of a neighboring block as though he lived there, that day, that moment when she had encountered him crossing the narrow bridge at Dund Gol, she had smiled in amazement as she watched him, and had thought about him all day. She had walked some distance behind him, and he had suddenly bent down and, taking a light blue offering scarf which seemed to have fallen on the ground, shaken away the dirt and, tying it carefully to the railings of the bridge, walked off. Seeing this, the woman had smiled in surprise. Perhaps nobody out for a walk had thought to pick up that offering scarf, which had been lying underfoot. The woman had stopped walking to observe closely the young man’s every movement, how he had bent down suddenly, picked up the offering scarf from the ground, shaken away the dirt, and carefully tied it to the railings of the bridge. Once she had arrived at work, she had smiled, thinking with some of her previous warmth and affection of that young man whose face she recognized from the neighboring block. The next time they encountered one another, she greeted him as though he were someone she had known for a while. The young man was shocked, but responded in kind, weakly nodding his head. And now even this unknown yet familiar monk sat reading, weakly nodding his head over his text, in exactly the same way as her departed lover had weakly nodded his head to her that day. The woman looked at the ground, wiping her tears with her sleeve. Concerned that there were people all around her, she felt embarrassed for crying at seeing a monk sitting there, reciting mantras. It was as though she was dreaming. In order to awaken from her dream, she shut her eyes, head bowed.

The monks harmonized as they recited, and the young men’s voices, led by the chant master, made the thick air of the monastery thicker. The mantras, which had peeled away, letter by letter, from the drum of the prayer wheel and flown through the sky, now began to float, word by word, in the air. Then one of the many rumbling, droning voices slowly broke away, and the words of the mantra that mounted the voice caused it to rise into the air of the temple; they began to float it towards the woman, who was sitting by the door, peering down at the ground, letting it fall gently into her ears.

To her teary eyes, the toes of her shoes shimmered like the vision of a ship sinking into the great ocean. The great ocean extended beyond her eyelids and crashed onto her eyelashes, and in the instant that the ocean came crashing down it became two droplets on the toes of her shoes; she could see her shoes clearly. At that very moment, a voice that she knew well, familiar but no louder than any of the others, came rumbling into her ears. The woman opened her eyes in surprise, and as though hearing a noise stopped a moment and then raised her gaze to look once again at the monk. The monk was ringing a bell as he read the text, and a moment later, parallel with the ringing of the bell, he intoned the name of the deceased—“Setgeltogtuun,” or Calm-minded—from the piece of white paper that lay on his left palm. She felt now even more disturbed. This was the voice that, the last time they had seen each other, had said to her, “Calm yourself! Let’s talk tomorrow when you’ve calmed down.”

As he had said this and walked toward the door, she had remained lying there, looking away because of her anger. Beyond the sound of shoes being put back on, of clothes being taken from the racks, there had been the sound of the door, and beyond that the sound of light steps on the stairs outside, gradually fading away. How could she have known that the sounds of his simple acts would eternally fade away from her life? He didn’t come to talk the next day. Neither the day after that, nor the day after that—there were no phone calls, the doorbell didn’t ring, and there were no green signs showing that he was online. Though it had been a long time since he had moved away from the block next to her apartment, it wasn’t much of a trek back. After waiting three days, during which time she would jump up at any noise, she sent a message: “Please just go away!” He had indeed gone away. But it was not he who had read the line that told him to go away; it may have been the police, his mother, or his relatives. Still, the police had not called her in for questioning. His mother had not called and cursed her. His relatives had not brought her low with harsh words. Nobody had paid attention to the woman. Nobody had bothered about her, as though they all assumed that she was nobody to the family. She had heard the news not from his family members, but from a woman who enjoyed gossip: how “Four days earlier, when he came home at night, his family was fighting with each other. He had tried to stop the fighting . . . Afterward, apparently, one of his stepdad’s sons was arrested.” While she had been speaking, that gossipy young woman had been swinging her legs and playing with her phone. This was three days before she had sent the “Please just go away!” message. But to her it seemed that he had gone because of what she had written, and the thought tortured her terribly. She was also thinking how dreadful it must have been for him to be kicked out by his lover and killed by a member of his own family. But now, in front of her, he was sitting in his former vibrant form, saying prayers for his own future rebirth, ringing a bell, and with his gentle and harmonious voice, saying, “Setgeltogtun. Calm mind . . . calm mind . . . calm mind . . . ”

The tears came again. She looked directly at the monk’s every movement as she sat there uneasily, wiping away her tears, and then before she realized it, the prayers had been said and the service had ended. Some of the faithful rose from their seats and filed into the center of the hall to receive blessings from the monks. A young girl, pregnant but with a small belly, accompanied by her mother, joined the back of the line, and bowed to receive a blessing from the monk who was sitting at the end of the line. Then she took two steps forward and pressed her belly and said something into the ear of her mother, who had been walking in front, her palms pressed together. They smiled as they spoke together, and once they had passed from one monk to another to receive blessings, they headed directly for the door. In a loud voice, the pregnant girl said, “When I got up from being blessed by the first monk, it felt like something was pushing inside me. I think that was the quickening.” The mother put her hand on her daughter’s belly, and they went out smiling and talking together. The woman, sitting near the door of the temple, listened to their conversation, and looked at the pregnant young girl, and let her eyes follow her. After that she slowly turned again to look at the monk. He seemed to have closed his text and was wrapping it up. The woman did not rise from her seat, but stayed where she was, filling her eyes with the living, bright, clear image of that person who would go out now, and would once again be completely wiped away from her life.

The monk rose from his seat, and as he put a few items inside his robe, he included there the piece of white paper with the name of the deceased. The woman hurried to rise from where she was sitting. She went out of the door and waited there for him. The monk did not come out. She waited for a while. The woman took a deep breath, and when she looked back through the open door, he was nowhere to be seen. At that moment, a magical thought came to her. She had wept for what she had written—Please just go away! But now she thought that perhaps he hadn’t gone away forever as she had said, and had come to show himself for the final time! As soon as this thought came to her mind, it seemed that the regret she felt lightened a little, as though something hard in her chest had been crushed, and she felt calmer. As she left the enclosure where the three temples were, she kept on looking back. But she couldn’t leave Gandan immediately. She felt drawn to the place.

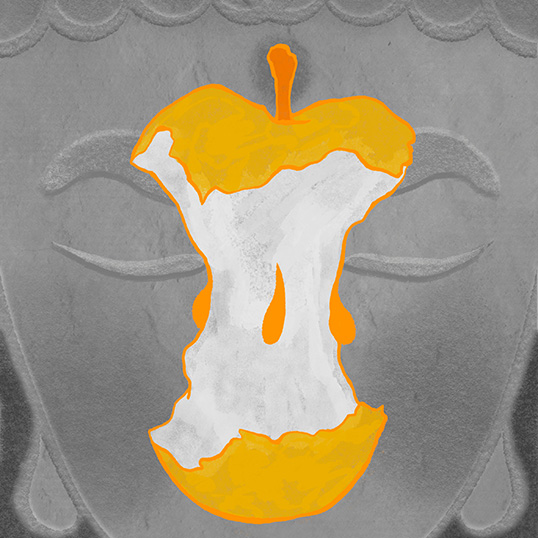

The bag of an elderly woman who was walking ahead of her had come apart, and the apples that had been inside were scattered all over the ground. She came to her senses and moved to help the old woman, but two young boys descended and began to rush about, gathering up the apples like field larks pecking grain on the ground. The woman had thought to help, but now there was no reason to do so, and she sat watching the boys on a nearby chair. The old lady offered a prayer - “Oh what kind children - may you get merit from this!” She gave each of them an apple as a reward, and they nudged each other and ran off. The old woman clutched her bag of apples to her chest and walked away.

Perhaps because she hadn’t eaten a thing since the two spoonfuls of rice mixed with raisins that morning before she had left home, the woman’s stomach was growling. She put her hand on her flat belly. It was as though, inside her belly, there was a meteor shower in the endless darkness of the desolate universe, that planets were colliding, and that an enormous black hole was twisting everything and sucking it in. As she pressed her belly, she thought about the pregnant young woman. She felt love and jealousy at the same time. She thought that she had rescued the soul of her man, which had been wandering through the utter darkness of limitless space, through the star storms, and had helped him find his way back to the world. If only I were in her place! she said to herself. She thought this as she laid her palm against her flat stomach.

In the sunshine just before midday, the air was beginning to warm up. Her thoughts were utterly clear as the heat of the air started to burn her head, and then, gradually, they dispersed, leaving her at a loss. Who knows how long she’d been sitting there? Suddenly she saw the monk from earlier: he had stopped and was looking down. He picked up an apple from the ground and wiped it with his sleeve. Just as, on such a sparkling spring day, on the narrow bridge at Dund Gol, he had suddenly stopped, bent down, and picked from the ground a light blue offering scarf, shaking off the dirt, so this monk had picked up an apple from the ground, rubbed off the dirt with his hand, and wiped it on the sleeve of his deel. The woman watched the young monk absent-mindedly, and then, as though suddenly coming to, rose quickly from her seat and approached him, extending her hands. The monk was not surprised to see the woman standing there, extending her hands. He smiled at her without a word. He poked around inside his deel and took out the piece of paper on which a text to be recited had been written, and with this piece of paper he wiped the apple. He put the apple in one of her hands, and the piece of paper in the other, and went off smiling in that way she knew so well. The woman clutched the apple and the piece of paper and stood watching the monk until he turned the corner. He walked deliberately, and with no urgency, around the corner. There she stopped, watching his every step as he walked away from her. After he had turned another corner, she stood there.

But how long would he be there? She went and sat on the chair where she had been sitting previously. As the monk had turned the corner, the image of the man she loved had disappeared completely from the world. The woman recalled the moment when the two of them had stood on the old wooden bridge, watching the flow of the river. She had wanted to take a photograph, but he had kept resisting such that she could only snatch a single picture.

“Do you really not want to take a picture with me?”

“It’s not that.”

“So why are you resisting?”

“I’m just not comfortable.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. It doesn’t feel right.”

“What is it?”

“I can’t explain it. When someone dies, we put a picture in a frame and offer candles before it. We don’t know when we’ll die, but we leave at least one photo in which we stand tall, looking directly at the camera, as though we do know which photo we would leave behind to be framed.”

“Is a young man like you really worried about the picture for your funeral?”

“It’s not that. I won’t be able to choose the picture that gets put in a frame, but still I want to choose the moments which won’t end up in a frame. This moment with you, for instance . . . ”

As he said so, he smiled awkwardly. When she recalled this moment, she thought how indeed she should have documented those moments when the two of them had been together, at whatever instant, and in whichever corner of the world, so that she could prove it to others. And she had wanted to walk over the threshold of his house and be introduced to his mother. But that was nonsense too. Their love did not need the approval of others to be true, and even if others had not been consulted about their relationship, it didn’t mean it was a lie.

The sun was now at its highest point. All the old women who had been selling rice were sitting in the shadow of Gandan’s high monastery walls. The line of worshippers had gradually slowed as the heat had intensified, and now Gandan was graced with silence. She heard a car horn, and the driver stuck his head through the window and asked, “Do you want a ride?” The woman revived, nodded her head, ran to the car, and got onto the back seat. Her stomach was growling. She took large bites out of the apple in her hand. As she ate, she looked at the piece of paper the monk had given to her. As she guessed, neither the name of a text she ordered to be recited, nor the total amount she paid were on the paper. One side of the paper was blank, but on the other side there was a single, clear, word, her lover’s name: “Setgeltogtuun.” Calm mind. She continued to eat the apple, taking large bites, swallowing the seeds too, while staring at the paper. As she finished the apple, she felt calm, her belly satisfied. And now with her warm palm, the woman gently pressed her belly which contained the seed she had taken from Setgeltogtuun. Eventually, Setgeltogtuun’s seed had been planted in her belly. She leant against the back seat of the car, and closed her eyes. And she smiled. She smiled . . . she kept smiling, and she whispered to herself, “The Buddha’s language . . . ”