Cristina’s mother hadn’t objected to the fungus, which didn’t require a lot of maintenance or take up much space, but then her husband died and she made her daughter get rid of the disgusting thing. It was a brown fungus, rectangular and flat. Cristina kept it in a glass Pyrex dish, oven- and freezer-safe. After the cremation, she passed it along to her friend, who lived on the floor below. All the building’s residents came home from the funeral together, but most of them said goodbye at the elevator, and few entered the deceased’s apartment. The downstairs neighbor hadn’t made it to the funeral home. When her parents returned, they brought her upstairs to keep the fatherless girl company. The departed had been a building engineer and traveled frequently to visit worksites. He had already upgraded to a Mercedes, and felt safer on the highway. That car was a tank, his widow would say, but then a crane fell on top of it; despite the reinforced bodywork, its owner ended up crushed between sheets of metal. They incinerated the body immediately and placed a photograph beside the urn to greet the mourners. He was a good-looking man, with big blue eyes that his daughter had not inherited.

Cristina and the downstairs neighbor went to the same school, but weren’t in the same class. They had struck up a friendship playing Barbies in the building’s stairwell. When her father told her to go upstairs, the downstairs girl wanted to rise to the occasion. She thought death seemed pretty strange. For starters, and speaking only in theory, if her own father died in a workplace accident, she would prefer not to see her neighbors at all, instead letting her sobs tumble out while hugging her sister until sleep found them both, their eyes swollen from crying. But this might just be another of her eccentricities. In the deceased’s apartment, the rear service door off the kitchen was open. The two fatherless boys stood there, receiving the visitors. They welcomed the downstairs neighbor with thankful and sincere affection they had never before shown her. She said “I’m sorry,” quietly, because the boys intimidated her and she wasn’t sure how you were supposed to express condolences. She blushed. The older brother rescued her from embarrassment, pointing her toward the master bedroom. Cristina was alone on the balcony, looking out at the street, and she seemed pretty normal, more so than her neighbor had expected. They exchanged a couple of pleasantries and Cristina confessed that their friendship had always annoyed her father, because he couldn’t stand them playing on the stairway landings, like a couple of homeless children. Then she told her neighbor about the sculptures that her dead father “builds” in the city, using the present tense, as if language could somehow hold out against death. No one in the city knew it, because the artist didn’t like to brag, preferring to keep his talent a secret and just be the neighbor in apartment 2R. Cristina told her that his most recent commission had been the trash cans in the main square, and the downstairs friend marveled at how little we know about people’s lives. Cristina had never mentioned her father before, and now she had no time to connect her stories about what had made him special. When she ran out of anecdotes, she grabbed her neighbor’s arm, pulling her into her bedroom.

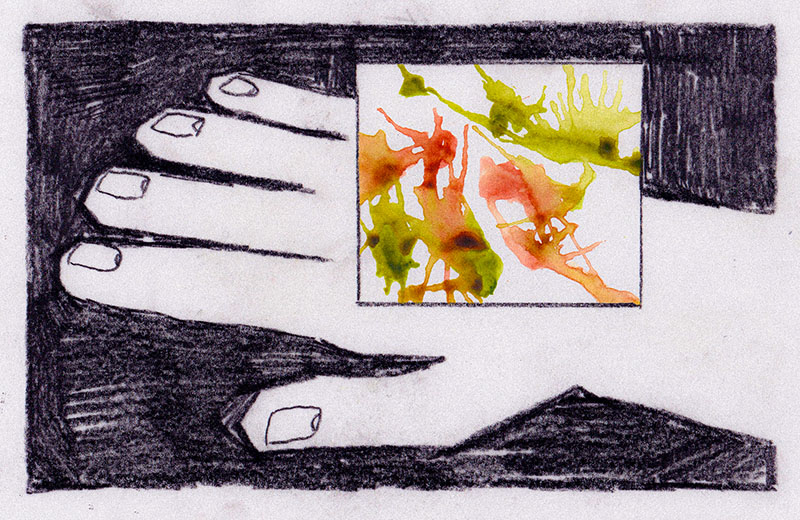

Cristina’s room was the smallest one in the apartment, and when she opened the door, they were hit with a moldy stench, like expired yogurt. She was already familiar with the appearance and qualities of the magical fungus that had been all the rage at their school for the last few months. Each girl received a child-fungus that became a mother once it was adopted, then she made a wish. For it to come true, the wisher had to feed the creature with a glass of water per day, like a plant. The fungus produced a child-fungus within a week, which was then separated horizontally with a spatula or a knife, and entrusted to its new caregiver. They were very resilient. That winter’s Olympic boredom had sparked the popularity of the fungi, and once the first blob appeared all the girls wanted one. They spread like wildfire, so much so that there was an overabundance of children and they were exported to other schools where (perhaps because those schools were co-ed) the fungi weren’t so successful. From the second week of March onward, the transfer became the greatest challenge of the whole process. Once the three child fungi had been distributed, the mother fungus was left to dry out, her dwindled body becoming a talisman for the wish’s fulfillment. But that morning, the new widow had given Cristina an ultimatum: “Either you get rid of that thing, or I swear when we get home I’m flushing it down the toilet.” Then they had gone to the funeral parlor, where the fungus had no business being.

“It’s the last child I have,” Cristina said, “and I’ve already promised it to Beatriz Sierra. You don’t have to do anything except water it and it’ll give you the child in three days. Then you let it dry out and give me whatever’s left. They say it can be tiny, because it’s almost all water.”

The downstairs neighbor observed its bulging viscosity and thought it looked like a flan that hadn’t set properly. She asked Cristina where to cut it; her friend pointed, as though it was crushingly obvious. She thought Cristina had chosen the spot arbitrarily, but it wasn’t the moment to fight with a fatherless girl about her own fungus. She would figure it out.

Beatriz Sierra hadn’t been to class in almost a month. Everyone knew she was anorexic, and since the beginning of the school year they had watched her lose weight without any great panic. They were used to fluctuating weights. After developing, bodies went crazy: the fat girls got skinny, the skinny girls got fat and the short ones got tall. Until Beatriz fainted in History class, no one had any clue about the gravity of her situation. From then on, she was absent a lot. Her sick days became more and more habitual, and finally she just stopped coming. Then Lola, the gym teacher, went from class to class talking about adolescent dietary problems. Thanks to that lecture, the downstairs neighbor found out what anorexia was. She learned that the illness also weakened the mind and that anorexics hallucinated: that’s why, when they look at themselves in the mirror, instead of perceiving reality the way it really is, they look fat, like toads covered with flesh. They also taught the girls about bulimia and the different ways to make yourself throw up.

The day before the fungus child separation, the downstairs neighbor, as its new guardian, arranged to meet with Beatriz Sierra’s mother. Her classmate wouldn’t come to the phone. Mrs. Sierra insisted that she visit the next day, because even though Beatriz was weak, she loved visits. The fungus detached easily, and the difference between the two skins was clear. For its transport she picked a plastic plate, on which the little oozing and viscous body looked like a cold chocolate dessert. Mrs. Sierra received the girl enthusiastically, despite the fact that she and Beatriz weren’t close. She asked her to wait in the living room and went to look for her daughter. She returned dragging a strengthless animal hidden under layers of pastel clothing. There was extra fabric everywhere, like a baby swaddled in an enormous shawl. The visitor hadn’t known people could get so tiny. Calves smaller than the diameter of her wrists peeked out from under the pink robe. Enlarged by the size of her body, Beatriz’s slippers dragged painfully, like they were made of iron instead of plush. Beatriz, the Beatriz from school, had been watered down to her bones. Mrs. Sierra was practically carrying her in her arms. At no moment did she lift her eyes, widened by the retreat of her flesh, to acknowledge her schoolmate. The sick girl’s mouth was half open, and her chapped lips formed an expression of disgust. She tripped before making it into the chair.

“Are you ok, sweetie?”

The daughter responded with a tiny nod of her head, asking to be taken back to her room. In that gesture, the visitor at last made out something resembling the classmate she had once known. Beatriz’s eyes had a taciturn look from the way her eyelids lowered. Without saying a word, the anorexic returned to her room. The guest stood up, convinced of the necessity of retreat.

“I hope Beatriz gets better soon. I’ll leave her this.” And before she had time to take the fungus out of the bag, Mrs. Sierra interrupted her.

“No, please, give it to her yourself. It’s really good for her to see people, take her mind off things. Now go along to her room. She’ll seem a little out of it—it’s the medicine, it really tires her out.”

“Ok.” The teenager felt like she was getting herself into a mess, but she didn’t have it in her to let the mother down. “Which way?”

The smell of hospital food, mixed with other sickly-sweet medicinal body odors, permeated the walls. Once inside the room, smell eclipsed her other senses, partly because with the blinds down she couldn’t even make out the shapes of the furniture. She imagined Beatriz in the bed, so light that she didn’t even make a dent in the mattress, like a sheet of paper.

“Come closer, that way I don’t have to talk so loud.”

Her proximity to death endowed the sick girl with ancient authority, like an oracle.

“Every time I fall asleep, I dream that there’s a black shadow that comes and pulls me out of bed.”

“How much do you weigh?”

“Seventy-five pounds,” the recumbent girl replied with a certain pride. “They say that if I get to seventy-three I’ll die. That’s why they drug me, so I don’t use any energy.”

Last year, Beatriz had played tennis and been a point guard in basketball. She used to be a muscular, agile girl.

“Before, when I couldn’t sleep at night, I used to exercise here in my room. Now I don’t even move.”

“That’s better, that way you can rest.” Once she got used to the dark, she found Beatriz’s exhausted eyes looking for hers. “Do you really think you look fat?”

“Not anymore. I’d stay like this, but I’m scared to die.”

“I think you looked better before.”

“And what do I care what you think . . . ” Beatriz stopped herself just before adding “fatty,” and the silence was worse than the insult. The visitor filled the void with the girth of her body, feeling enormous, half her flesh suddenly feeling superfluous next to the emaciated figure who, even without muscles, still had her claws out.

“Why did you come?”

She could have made something up, or simply said, “to see you,” but it seemed wrong to lie to someone two pounds away from death.

“I came because Cristina’s father died and she asked me to give you this,” she said, as she took the plate out of the bag.

Beatriz sniffed the object as it approached her.

“What is it?” she asked, terrified.

She peeled back the tinfoil so Beatriz could see it, and the brown fungus elicited a reaction of abject terror. The sick girl clenched the few muscles she had left, pushing away the plate with a titanic effort and growling:

“You brought me a dessert?” The sick girl’s dead eyes fixed on her with piercing rage, and she called her mother to eject the visitor, who was delighted to leave.

On her bedroom nightstand, the old fungus was beginning to disappear. She would wait until it dried out completely to bring it upstairs to Cristina. She placed it on top of the tinfoil covering on the one Beatriz had rejected, tilted the plate over the Pyrex, and the new mother-fungus slid in like an enormous slug, leaving a trail of bubbles behind. She felt overabundant again, and thought maybe she could wash away her excess with a shower. She dried off in front of the mirror, moving little by little so she could catch an image of herself that, until that moment, whether because of naiveté, absentmindedness, or negligence, hadn’t been so clear. She felt as if she was waking from a dream to the painful reality she had avoided until then, as if a spell had kept her holding on to an illusion, if not really of beauty, at least of a certain aesthetic normalcy, which now dissolved, without mercy or any possibility of improvement, in front of her very eyes. She faced her abnormal physiognomy in the solitude of the bathroom, retrospectively ashamed of the interminable hours in swimming lessons with her classmates, or family vacations on the beach. Only the dying girl had had the courage to put the reality of her appearance out in the open with that unspoken word. She closed her eyes and counted to ten very slowly because she, too, might have become infected by that perceptual problem that distorted the vision of anorexics and drove them to monstrosity. In this case, however, when she opened her eyes, the deformity remained. She needed a final test, and came up with a method to trace herself on a flat surface at life size. Her room smelled more and more like mold. She pressed herself up as hard as she could against the white door of her closet, turning her neck so that her cheek was touching the wood. Marker in hand, she traced the points she could reach from that position so as to achieve the tightest possible outline of the contours of her body. A mark at her shoulders, another at her armpits, a point at the waist, then her crotch and thighs, and back up. To finish the job, she outlined her head, squashing down her increasingly sparse hair. She stepped away, and without looking at the whole image, filled in the gaps with the colored marker until she drew a body, her body, which left no room for delusion. More than shame, what she felt was a deep desperation, and she asked herself how anyone could possibly continue to nourish the life of such an ugly organism as herself, especially now that all the other girls already had their talismans and she was condemned to the enclosure of the Pyrex.

II

There are people who think being a fungus or an insect, or suffering from any other kind of severe malformation, is a tragedy. For me, though, it’s been the most fascinating experience, stressful at times, but recommended without reservation. We fungi are neither animals nor plants, and we have such a wide variety of forms and species that some of us aren’t even related. Mycologists decide what counts as a fungus, and which fungal variety each one belongs to. Before I turned into one, my family and I didn’t know anything about fungi, but since then we’ve learned quite a bit. My mother noticed my absence immediately, but it took her a while to recognize me. This delay almost shriveled me. Approximately two hours after my conversion, my mother announced that dinner was ready, and when I didn’t show up at the table, she came looking for me. Everything happened so unexpectedly that I couldn’t warn her, and at first, she didn’t associate the viscous fungus growing in a glass container with her baby girl. I didn’t try screaming, and would’ve been disappointed if I had; we fungi lack vocal cords, lungs, and mouths with which to produce sounds. We are extraordinarily simple organisms, especially those in my watery group—we’re closer to algae than we are to mushrooms. Until you’ve been in this state it’s almost impossible to appreciate the complexity of human beings. We only have one type of cell, and they all serve the same function: survival. So there I was, in my Pyrex, on top of my sister’s desk, dying of hunger and killing my mother with worry. In that situation, the only possible actions would have required muscles or extremities or both at the same time, and we fungi have none of that. Feeling the end draw near, I pushed myself to come up with a survival plan, using the little water left in my body. I moved my liquid from side to side, in a slow and painful process that used up all my reserves but allowed me a certain amount of mobility. I reached the edge of the container, and with my last breath I flung the glass onto the floor, causing a commotion that enlightened my mother, the only person in the world capable of recognizing her daughter in such a monstrous and agonized state. Neither the nauseating smell nor the viscosity of my body spoiled the happiness of the reunion. My mother lifted me in her arms, drawing me to her warm chest, where I gave in to her love with the calm of a satisfied baby until my beloved guardian, in an unfortunate combination of her best intentions and minimal knowledge of fungal anatomy, placed me on my sister’s bed—a privilege I had never before enjoyed, despite the fact that Esther had been living in England for over a year. The sheets absorbed what little moisture I had left, and I shrank like a rotten fruit before the eyes of my horrified mother, who out of an instinct stronger than reason understood the moment’s urgency. My next memory as a fungus places me in the old fish tank where we used to keep two little carp, which my brother and I overfed until their insides burst. Luckily, we fungi don’t have stomachs, and in that fish tank I could grow as wide as I liked, multiplying my cells with the abundant waterings my family provided. I prospered to such a point that my parents moved me to their bathroom, to the bathtub, the biggest one in the whole house. That was without a doubt the most appropriate place for me. My father and my brother plugged up the faucet to make a trickling irrigation system so I could be fed at all times. The three of them learned a lot about aquatic fungi in the two, or three, or maybe seven weeks that we all lived together. Thanks to that invention, I was able to live constantly surrounded by a half inch of water, which I contaminated with my enzymes so as to feed on any particles I managed to break down. In that favorable setting, my growth was exponential. We fungi lack senses (only some animals are so lucky); however, we are sensitive to light. Even though I almost always had the lights off, this mechanism allowed me to detect the presence of my family members. My brother was the only one who didn’t turn the light on, but even so, a little bit came in whenever he opened the door. The one I kept easiest track of was my father, who came by every night before going to bed. Alerted by the luminosity of my environment, I tried to remember my humanity, and I could sense his downcast paternal face, and his failed attempts to hide his sorrow—like he wanted to tell me not to be ashamed, that we would get through this, because in the end, when horrible things become routine, their negative nature is dissolved in the quotidian, as the sheer force of repetition undoes its discomforts. His attempts at consoling me were moving. These feelings, unknown to any other fungus, prevented me from completely adopting my new nature. One by one, my eukaryotic cells multiplied with determination. In that serene state I became conscious of the multiplicity of components of which I was made, and I entered into contact with the rest of the identical fungi that populate the world. Our species has existed since time immemorial, long before humans appeared. The species dried out at the same time the Earth did, but even that deadly warming couldn’t destroy our spores, which held out patiently until the rains came, moving on to inhabit new waters and keep growing. The flood scattered us across the globe, from pond to pond, puddle to puddle.

Now, when my mother comes into the bathroom, she can’t hold me in her arms. I’ve grown so much that she doesn’t even crouch down properly. She rests her hand on whatever part of my anatomy she can, on what she thinks is my stomach; the soft keratin that covers me doesn’t even feel it. Then she goes over to the toilet seat and takes a break. From there she tells me about her day, putting it all in order as if I could hear her. She doesn’t know that I am traversing the history of existence through all my sibling fungi and that I am less and less present in this bathtub, in this story. When you live in the entire world, no language is required. I become present in all the cells that make up my body mass and in all the organisms with which I share, have shared, or will share the same protein sequences. My father gets increasingly worried, asking where my growth will end and trying to guide my mass toward the sink in one direction, toward the bidet in the other. He doesn’t want me to break. He doesn’t realize that my body is identical in each of its parts and that in fact I can reproduce that way, with a cut, and keep growing anywhere with fresh water. He grabs me and leads me one way or another. I feel my mother’s and my brother’s presence. Their tenderness makes it impossible to surrender fully to the biological totality in which I find myself, and here I remain, anchored to the memory of my humanity. I’ve been overflowing for days and no one comes into the bathroom anymore for fear of stepping on me. The door is stuck half-open and no one can move without bumping into my mass of cells. My mother doesn’t want my sister to quit her job and come back from England. Lost in the sound of the wind on which my spores traverse the storm, I am incapable of coherent succession, and for me it’s the same to witness the birth of the first marsupial in Australia as to watch the forbidden encounter between a lady resident and a nameless man, in a building where I started growing in the basement thanks to a leak. The doorman of that building refuses to touch me. I disgust him, and this repugnance saves me time and again. On the banks of the Seine, I grow alongside apathy toward death in the time of the great plagues. I know no fear; the rats of Paris in those days get even fatter than I do thanks to the amount of putrefaction on hand. The viruses they carry don’t mutate my cells. I possess a fragmented DNA that doesn’t fear the sound of the cannons either, in a time when an idiot, or a madman, or a sane one punished by hunger, mistakes me for food. The salty tears of one of his relatives will impede my journey through that poor starving man, in whom I will cause massive diarrhea, killing him without affection or regret, without guilt or desire, just the way I observe the thousands of bacteria that nourish, as I do, the tadpoles of a distant pond. Submerged in water, my parts cease to be, but I don’t. I continue existing and approach a perfect state of monstrous multiplicity. Don’t come back, better to keep your memories of her from before, keep working, I would hear, if I were able to, and I would know that the conversations had intensified on account of pressure from the neighbors. I cause dampness, and no air freshener is a match for the putrid stench of my enzymes. The move takes place in the wee hours of the morning. I can tell from the quality of the light, and because the neighbors still talk about the fungus girl, and I’ve compared their versions. My parents rent a truck with an open water tank. They assemble my aunts and uncles, cousins, and a couple of close friends. Between all of them, they remove me, wrapped in plastic. My mother allows only my brother to help her wrap me up, everyone else will touch me through this wrapper, in a titanic effort to save my spawn. Luckily, all this happens in the summer, and I don’t have to bankrupt my family with the purchase of a temperature control for the swimming pool at the vacation house in the mountains, where they’re taking me.

One day I wake up human again, swimming in my own excrement. I look up, identifying my brother, who despite his astonishment repeats my name and the story he’s been telling me, as if nothing had happened, like I’d never been a fungus, like I wasn’t covered with shit, naked in front of him, with my eyes swollen from the months of denial and weeping. Maybe you’d like to rest for a little while, he says, and I answer humanly that yes, I’ll rest for a while before getting dressed for dinner, and then he leaves discreetly and I can clearly hear my mother’s shouts of happiness. Now I’m missing a phalange on my middle finger. That part stayed fungus. Settled in the faucet that had fed me, it tore off during the move to the swimming pool. A minor detail, a scrape, which you don’t notice at first glance; but sometimes, when someone points toward my stump, or I myself look at it, I can feel the phantom remnant calling me with all its ancestral fungal force, and thus, every so often, I sail through its biographical thickness without destination or time, until, with no possible explanation, I find words once more.