Children are waiting in front of the post office. The woman sits downstage.

CHILD 1: When is he bringing them out.

CHILD 2: They’re already here.

GIRL: I know we have to wait, they will only come if we wait.

CHILD 3: Everybody knows that, but what’s the point of knowing when you’re so excited that you already need to vomit on your way here.

CHILD 1: Did you vomit?

CHILD 3: You never vomit?

CHILD 1: No, not really. I vomited last year but not this year.

CHILD 3: Same with me. I won’t vomit next year, but now I’m only in year three.

MOTHER: They waited there as they always did. I knew what was going on, as I often went myself, went with the child, so that she would know where to go, because I wasn’t always able to go, what with the animals and the land. The letters were sometimes despatched too late from the capital and didn’t get here until sometime in the afternoon. The children sat down on the roadside and chattered away, unable to keep still, so full of impatience were they for the post office door to open and the postmaster to come and distribute the letters at last. They couldn’t be still. They just had to be talking, and they talked about what they would talk about any other day.

CHILD 1: When is he bringing them?

MOTHER: When is he bringing them, one of the children asked, what else could he have said when the only reason they were there was for him to bring them out.

CHILD 2: Maybe you won’t get one, you know.

MOTHER: That’s what someone said, because it was like this: they thought if one of them was not getting any, the other would surely be getting one. It wasn’t something they dared to say out loud, but in their heads, they thought if the other child’s father had died, their own would surely be alive. They never thought of the possibility that both of them could have died or both could still be alive. They were like this. If one of them had died, then the other one had surely survived.

CHILD 1: And what if you’re the one not getting any.

CHILD 2: I’m getting one because I didn’t get one yesterday.

CHILD 1: I get one every day.

MOTHER: One of them was getting letters every day, or at least that was what he thought, because the days he didn’t get any didn’t count, although it wouldn’t have been possible for him to be getting one every day. I’m getting one every day, he said, and I knew whose son he was. Then they carried on talking, with one of them asking, quite suddenly, what it could be like there, and the other one said she didn’t know.

CHILD 3: What is it like there?

CHILD 2: I don’t know.

CHILD 1: Do they kill people?

CHILD 3: No, I’m sure they don’t. You’re not allowed to kill.

CHILD 1: Why are so many of them dying, then.

CHILD 3: From the war, because there’s a war going on.

CHILD 1: The war can’t kill you. Only another person can.

CHILD 2: Because you’re allowed to kill your enemy.

CHILD 4: And what if he dies?

CHILD 2: Serves him right. Why did he become an enemy in the first place?

CHILD 1: He’s coming. The door’s opening.

CHILD 3: Don’t be stupid.

CHILD 2: What?

CHILD 3: With that enemy thing.

CHILD 2: What’s wrong with it?

CHILD 3: Dad doesn’t even know that person. How can he be Dad’s enemy?

CHILD 2: Because they’re the baddies. Some people are baddies, you know.

CHILD 3: They have children, too.

CHILD 4: Even baddies get babies?

GIRL: Mummy said they went only because they had to, otherwise they would have shot them if they hadn’t gone, because they were ordered to, at least that was why Daddy went.

CHILD 4: Ordered to?

GIRL: Yes. You couldn’t just say, “I don’t want to.”

CHILD 3: You can order people to do things like that.

CHILD 2: It’s either you or them. If you let them, they will win, like in football, you know, the whole thing is like a big . . .

CHILD 1: Drop it, will you, this football story. It’s stupid. In football, you have goals and not dead people.

CHILD 2: But there you also . . .

CHILD 3: Shut up, will you? Leave that damn football.

CHILD 1: My father is a hero, and that’s why he’s there, because he’s a real hero. He’s defending all of us.

CHILD 2: For sure.

CHILD 3: I hate the war.

CHILD 2: So do I.

CHILD 1: He’s coming.

The door opens and the POSTMASTER steps out with the letters.

MOTHER: Then the postmaster came out as he always did and started to distribute the letters. He knew everyone. He knew which child belonged to whom.

POSTMASTER: Here’s one for you. And one for you. There. Nothing for you today, I’m afraid.

GIRL: What about me?

MOTHER: Scared as she was, she asked, because the postmaster took pleasure in leaving this or that child out even when he had letters for them. That was what he was like. He wasn’t an evil person. This was only his way of making the child even happier, when he said, oh, my, how could I forget, and the child, sick with waiting to hear their name called, would it be at the beginning or towards the end of the queue, and not hearing it called . . . now this child who was like this, on the verge of tears, could cry with joy at last.

POSTMASTER: Wait a moment. Yes, this one’s for you.

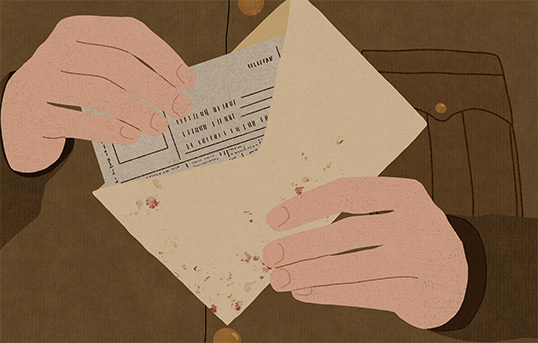

GIRL: I knew he’d write. I knew, because he didn’t write yesterday. I knew it!

MOTHER: Her joy was the same every time, the joy of a small girl as she inhaled in distinctive gasps, breathing in one breathful of air in three portions, with her face glowing as if the sun’s rays had bounced back onto her from the envelope. I knew her homeward walk. I knew she would stop at the bridge over the brook, where she was alone at last, and read. She would wipe her eyes. Her reading would stumble every now and then, perhaps because the writing was so terribly difficult to read, often written in tiny letters with a pencil, or perhaps because of what was written there.

Everyone runs home. The girl stops at the brook bridge and reads.

GIRL (reads, haltingly, repeating sentences and words): My lovely wife and sweet little Annie, I’m well and get enough to eat. My companions are decent people and we help one another out. I hope that you’re both well and managing the land and the animals, and that you’re not in danger. I miss you both terribly! I wish you many happy returns, Annie, and I’m sorry I couldn’t be there on your birthday, but believe me I shall be there for the next one. I kiss you both a million times, Daddy.

MOTHER: Each and every letter was the same, for these men were not used to expressing what was happening to them in writing. They had taken it for granted that others would just need to look at them to know how they were doing, but now it wasn’t possible for the others to look at them, for they were too far away to be seen at all. Every letter was the same, because if one was different, the scribe overseeing the soldiers’ letters would bounce it back, telling him to write another, similar to those the others were writing, and to the ones he had been writing himself before this last one was bounced back. The girl looked at the letter for a while, read it again, perhaps said that he was alive, or said so only in her thoughts, and ran.

GIRL: He’s alive! He’s healthy and alive!

MOTHER: He was alive, she said to herself, and she ran home to let Mummy know that he was alive. And she ran, though I didn’t see her yet, for the place she ran through wasn’t visible from the yard where I was, not far from the gate. Then all of a sudden, she ran into my field of vision, full of joy, her hand gripping the letter.

SCENE TWO

MOTHER: When she reached me, she held the letter up to my face and said, He’s alive, Mummy, he’s alive, and I told her that he was no more.

What’s no more, asked the child, her eyes staring at me. Eyes like her father’s, I thought, and I also thought, no, her eyes are just partly his, because they’re also partly my own, and I decided to focus on the fact they were my own.

GIRL: Mummy, what’s no more?

MOTHER: I told her that person was no more. Who are you talking about, which person, the child demanded.

GIRL: Who are you talking about, which person?

MOTHER: The one we have been expecting for so long.

GIRL: You mean Daddy.

MOTHER: Yes, I said, and my voice was no different than if I had said a number, one or two.

GIRL: This letter just arrived and I’ve read it already, and he’s doing fine.

MOTHER: The letter was written earlier. It happened while the letter was on its way.

GIRL: What happened while the letter was on its way? I don’t understand. What happened?

MOTHER: He died.

MOTHER: I told her that he died while she was bringing the letter home, stopping at the bridge over the brook to read it, and god knows how many times she’d read it there, many times, because she didn’t manage to read it through the first time round, partly because of her father’s handwriting, partly because her eyes kept welling up with tears and she couldn’t see the paper properly. Then in the meantime someone came from the post office with a telegram. She just looked at me, then at the letter, as if she were searching for something on me, in the letter, or somewhere in the air between the two of us.

GIRL: How could he die in such a short space of time?

SCENE THREE

MOTHER: How could he, in such a short space of time, she asked, and began afresh, but Mummy, he’s written. Here’s the letter, see? Here!

GIRL: He wrote that he was doing fine and that he was unhappy he can’t be here for my birthday.

MOTHER: The child said what she’d read in the letter. And I told her, or maybe just thought, I don’t remember now, that he wasn’t unhappy any more.

GIRL: Why not?

MOTHER: Why not, she asked, and I said because he wasn’t happy about anything any more, because it’s only us who can be unhappy now, he’s no more, and my voice didn’t change at all, pass me the salt, that’s what my voice was like.

GIRL: What do you mean, he’s no more?

MOTHER: What do you mean, he’s no more, she asked, and I said things weren’t like how they were in the letter, which says he is living and thinking about us. Things were different now. The telegram is about a later point in time than when he wrote the letter, because post is like this, a telegram can overtake a letter, and the telegram says that he’s died a hero’s death and that he doesn’t think about anything, not even about us, I said, before she had a chance to say he still thought about us, didn’t he? She didn’t ask what a hero’s death was like, how could death be anything, death is nothing but death, now a person is alive, the next moment he isn’t. And this death isn’t like someone dying old. It’s as if unripe fruit were torn away from the branches. Yes, people were still unripe when they got torn away from their lives and shoved into the ditches that soldiers had made villagers dig, just like it happened here in the village with the Russians. We didn’t know who they were, the enemies. Eh, enemies! They lived in our houses, bone-tired people, hungry, fatigued, went off to the River Garam the next day where the battle was, the corpses were carted back afterwards and they all went into the big ditch in front of the church. Some still groaned, others mumbled names. Whose names did they mumble? The names of someone they loved, but no one heard them, because for us those names had no meaning. They died, and no one heard their last words who would have understood them. He’d died a hero’s death, and his repatriation would be taken care of, said the telegram, and he’d been awarded the Small Silver Cross because he’d died. He didn’t die, said the child.

GIRL: Mummy, he didn’t die. Here’s the letter and I believe that it tells the truth. There must be a mistake. It shouldn’t be us getting that telegram, not us, and they must have written Daddy’s name on it by mistake that it was him. In the war everything must be all over the place. Mummy, the person who died is somebody else. I know it can’t be Daddy.

MOTHER: I think I told her they don’t make such mistakes over there, they don’t make mistakes in death, because that’s what they’re like, only being able to speak the language of death, about things becoming scarcer, such as ammunition and people. Everyone speaks this language over there, regardless of whether they’re Germans or Russians, although they face each other, they understand each other, having forgotten their own languages and found this common language instead. He’s died and from now on we must live knowing he isn’t any more. From now on, that’s how we’ll have to go to work in the fields, that’s how we’ll have to go to church, that’s how we’ll have to go visit relatives, just the two of us, while those people have more people. And we mustn’t think of missing him, and the only thing left for us to bear in mind is that he is no more.

GIRL: He isn’t dead to me!

MOTHER: He isn’t dead to her, the child said then, not to me. To me he’s alive. I let her believe that. I didn’t want it to hurt. She had never had much of a father to begin with, for as soon as she was born, he was drafted into the army, and although he was allowed home every now and then, later he was taken to the front for good. So she never had a father, only some sort of an idea of a father, and she was waiting for that idea, not the real person, for a real father she never had.

What will it be like, I thought to myself, when the others come home and I see them overjoyed, oh my god, you’re back, and they’re all happy, and here I am without anyone to wait for. Only a coffin will be coming my way, free of charge, because the state is taking care of repatriation, funeral, everything. This is the payment for a hero’s death.

SCENE FIVE

MOTHER: Then the coffin arrived, a tiny coffin, although my husband had been a big man. They said I wasn’t allowed to take a look at him because the explosion had completely torn him apart, because it was an explosion, mines of some sort, that’s what the unit had stepped on not knowing they were there, and everyone flew up in the air so that the pieces had to be gathered together and assembled again to see what belonged to whom, one of his companions wrote to me later. He had survived, having fallen behind unintentionally. Perhaps he had to retch for fear, raising his head only to find his companions’ body parts flying scattered in the air. The bodies of his companions, he wrote, although a minute ago they had shared a joke and talked about the marvellous paprika chicken with dumplings their wives made—thinking about that was a bit like being at home—and the bodies of these companions, ripped apart, bloody and mixed with mud, got blown up into the sky. As for himself, he’s been unable to return home ever since, lying as he is in hospital, and the pills he’s given are supposed to make the image fade in his head, but the image refuses to fade and instead carries on running despite the medication, and his doctors are of the opinion that if the pills make him sleep, then the treatment is successful, even though his dreams too are filled with the image, so he wakes drenched in sweat only to continue seeing it in his waking hours. How small it is, said the women. How on earth could that big beefy man become so small. I heard everything they said because I was there when they said these things, and they were saying them everywhere, next to me, behind me. They were there because they were expected to come in situations like this and experience how someone had lost the person who was, for them, still alive.

SCENE NINE

MOTHER: It happens sometimes that the father isn’t around because he’s disappeared or died, or just won’t come home. He’s gone off somewhere and no amount of waiting can bring him back. A last letter arrives from across the ocean saying we can follow him once he’s earned enough money, but no more letters come, because the money that would have been enough is now needed for another person, other children. And then it’s like this: without him. That it’s me and the child and no other person, not even the memory of the other person. No, I didn’t want anyone else instead of him. They would come, on their way home from the tavern. They were already back home, back from imprisonment, all of them allowed to return. They were emaciated and grey with shoebox-like skin, but transformed back into local people after a while, at least on the outside, for no one could know what hid in the deepest recesses of those hearts, which they had lugged home from the war and prisoners of war camps.

They came from the tavern and shouted through the gate how they would want to come in. It would do them good and do me good as well, for we share the same hardship, namely that they aren’t getting it because their wives had become like this: they don’t want it and come up with all sorts of reasons why not, the simple truth being that they had gone off men, which is to say the thing I thought was good had turned bad for their wives, namely the fact that the men had returned. At first it looked like all was fine, but the women later said to those war-weary men how long it had been with them not around and they had imagined them to be different, not the way they were when they returned at last. And it would be no use for the men to tell them how it was where they had been, what had made them turn out the way they had, for no one could possibly imagine that, only those who had been there. So they keep mum about it, just like the women keep mum about how it was while the men were not at home. They just don’t want it any more, they said as they walked home from the tavern, and that I would surely enjoy it with them, missing as I am the same thing they are missing, but I wasn’t going to let them in, no way. The last thing I needed was for them to breathe into my bed and leave their smell lingering there the following day. Or for the child to wake up and ask, what is Mr Laci doing in our house, what is Mr Imre doing in our house? For her to cry out on glimpsing the man in the bed, I told you Daddy will come back, and when running up to the bed only to find that the man with whom her mother cuddles and now she herself cuddles is not her father after all, but the father of one of her classmates from the street.

In vain was all their loud boasting about how big they were, their frantic grabbing of their crotches in front of my gate. I knew they shouted and grabbed so that the deed would be done, which in fact never got to be done. They were like this: they said, and the women thought so too, that I wanted what they themselves didn’t, as I hadn’t ended up loathing my husband, for he hadn’t come home for me to end up loathing him. They whispered behind my back that Anna was having visitors. She must be. Some of the men, after having a glass too many, actually thought they’d been in my house and went on telling everyone who’d listen in the tavern that with me, it was something the like of which they’d never felt before, not even when they had done it for the very first time in their lives. The other men in turn would be jealous to hear they had managed to pull it off. Even the priest asked me about it when I went to confession, prodding me if I had told him everything. Yes, everything, I said.

That’s not much, said the priest.

What else, I said, what else should I say. No situation has arisen where a sin could be committed.

PRIEST: There is surely something you have to tell me.

MOTHER: What, I asked, unaware of what he had on his mind, whereupon he named a man who had confessed to a sin he had not committed, for he didn’t remember not committing it, but the priest was certain it had happened, and was now waiting for me to confess to it. He told me he would come by to see how things were in my house, if everything was as it should be. A family visit, he said, a broken family visit, he added, laughing at the “broken”. When he came by later, he asked the child something, if she was still waiting for her father, and the child said yes and he would come, because she’d been praying for him. To this I retorted that praying was good for nothing, especially not for things like that. It was indeed good, and I shouldn’t be telling the child such things, said the priest, because she would end up not believing in God, not believing that God is omnipotent, able to do anything. Things he’d already done by destroying that person, for example. Things like that, too. He can’t be omnipotent, if what he creates is not everlasting, can he, I asked the priest but he had no idea what I was on about, and in the end nor did I, only sensing a deep-seated anger against this being who had created a world where people perish like that. Why would I want his name to be hallowed, why would I want his kingdom to come? What sort of kingdom is that? Why should he have his will? What sort of will is that? What a lot of nonsense, I thought to myself, and I will never utter this prayer any more in my life, not wanting anything at all from a god like this, not wanting him to want anything from me, either. From now on, we should be strangers to each other, and he shouldn’t reside in the place inside me where he used to.

PRIEST: Shouldn’t the child go to bed now?

MOTHER: He said, shouldn’t the child go to bed. Yes, I said, go to bed, sweetie.

GIRL: I don’t want to just yet.

MOTHER: Why not?

GIRL: Perhaps Father will tell me more about Daddy, where he is now.

MOTHER: He won’t be telling any more stories, I told you.

PRIEST: I don’t know where he is.

MOTHER: Then the priest said he didn’t know. Don’t you, the child asked, because it hurt her to hear that the priest knew way less than she did, even though he lived partly in the church and partly right next to it in the presbytery, and with that she went into the bedroom. When the door closed behind the child, the priest asked if I still had some pálinka left from last year’s brew. I said I had it all, I hadn’t wanted to sell any of it because I didn’t want the men to frequent my house, and I myself don’t drink. Will you be so good as to pour me a glass, said the priest. I could really do with a glass this evening. There’s only the evening prayer and some Bible study left. Of course, I said, taking the bottle out of the cupboard to serve him. As I passed him the glass, he reached out a hand, his right hand, but with the other he grabbed me from behind and pressed my skirt against my body with his palm. What can you do in this situation. I don’t know what you’re supposed to do. My face flushed and then: No, Father, it’s wrong. Your vows don’t allow this, not for a priest. But he said of course it is possible. He will go to confession where his friend sits in the confessional and will tell him all and receive absolution from him. It goes the other way, too, when his friend does it. They have this agreement. But Father, I said, and I was now able to push his hand away, although the trace of the hand had brought heat into me. No, do you understand, no!

What’s no, the child ran out of the room, and the priest went red. It’s the pálinka, he stammered, the pálinka’s gone to my head.

PRIEST: The pálinka, it was the pálinka.

MOTHER: He said it was the pálinka’s fault. What’s no, asked the girl, but the priest said nothing except good night and that he’d drop in again on a family visit, but he never came and even turned his head away when we crossed paths in the street. Which in turn led other people to believe that was because he knew my sins, though he himself had sinned. But who on earth would think a priest could be a sinner, at most those who he’d tried to do the same with and who did do it with him, but not me. Not that it made much of a difference, because I was never to be right, what with the very different truth the others believed about me.

SCENE EIGHTEEN

MOTHER: There we were, working by ourselves, but also together, and we called out to each other, shall we have a little sit-down, and we did. There was a walnut tree, and we sat down under that tree, then some women started saying things that made us all laugh. Old stories about people no longer alive and sometimes about people still around, and one of them said, do you remember him, here she said a man’s name, who wasn’t drafted because one of his legs was shorter, that was how he was born, and what a popular man this cripple became after all the real men were gone. How “who’s a man” is not an absolute truth, only relative. If he’s the only one there is to be had, you don’t mind what he’s like and he’ll be the real man, they laughed, and that time was like heaven for this man, and they laughed again, how all those pretty women made do with this man, although while the others were still at home, they would have never shared themselves with him, and there came a list of all the women that ended up making do with him but they didn’t include themselves, because they didn’t want to let it slip that they, too, had made do with him, wanting to think they hadn’t. We took up work again, laughing still at something or other, mentioning again the one with the gammy leg, who became the village stallion for some years. This was the word someone actually used. One of the women there was good at saying funny things and laughing, and if someone starts laughing, the rest will also laugh along with her, and then it’s impossible to know what you’re laughing about. Maybe we were only laughing at the laughing itself, when all of a sudden someone said, there’s a man walking along the road. We could see the road from there.

Where, one woman asked.

WOMAN: There, can’t you see?

ANOTHER WOMAN: Not me, not even the church spire.

MOTHER: Said the other and they laughed, and then she said, there truly is. A man, but who can he be.

WOMAN: A big beefy kind of man, isn’t he.

ANOTHER WOMAN: How can you see he’s big and beefy, when he’s at a distance where everything is small.

WOMAN: Because I can see him. If the man were smaller, then he would appear smaller.

ANOTHER WOMAN: What?

MOTHER: What, asked the other woman, what are you talking about.

WOMAN: Never mind, you don’t understand.

ANOTHER WOMAN: I understand, why wouldn’t I, I’m not stupid.

MOTHER: We laughed at her, the way she said “stupid”. Then we went back to looking at the man walking along the road, with a sack on his back, all alone like a corn cob flung into a corner. What’s that doing there, when all the others are stacked together in the corn crib, what’s this one doing here on the floor in the kitchen corner? He walked on, this man, and as he approached, he grew bigger. I saw it well. Only the old ones couldn’t see, but those of my age could see very well. He was approaching, and one of them says, wait, Anna, isn’t that your husband?

WOMAN: Wait, Anna, isn’t that your husband?

MOTHER: This was what she asked, and I said, you’re talking nonsense now. You know very well where mine is. But it is, she said again.

WOMAN: That man looks just like your husband.

MOTHER: He may well look just like him, but can’t be him, only like him, I said. And the man was coming nearer and nearer, and I saw, at first only barely, then properly, that he was indeed my own husband. Then I was happy and dropped the hoe. That’s my husband, I said, not hearing the other woman say, who’s in the coffin then. My husband, really, I went on being happy as you’re expected to be in situations like this, but not deep down in my heart, for the depth of my heart was already empty, the man who just returned wasn’t in it any more, because the one who was once there could never return. But I did what I had to in situations like this. I ran up to him, János, and said what I had to say in situations like this, is that really you? The others also came running, as expected in such situations. Is that you, János!

MAN: It’s me, Anna, love. I’m here, I’ve come home.

MOTHER: You’re alive, I asked him, I just had to ask him if he was still alive, because he wasn’t alive to me any more, to me he was dead, and he was dead to everyone who knew him.

MAN: I’m alive, Anna, sweetheart.

MOTHER: He said he was alive. Did you think I wasn’t, he asked. Yes, I did, I said, because they sent you home in a coffin some time ago. What, he asked. They wrote you were dead, and we had already buried you. He didn’t understand a word I was saying. What are you talking about, he asked, and I told him what it was, and he laughed. How strange it must be now that he was here. Yes, strange, I thought to myself, and that it was unusual for a person to exist, when he is actually no more.

MAN: The little one?

MOTHER: At school, I said.

MAN: Shall we go pick her up?

MOTHER: I said that the hoeing, that it needed to be done first. I really don’t know why I talked about hoeing, maybe I wanted to say something that was real, and hoeing was there and real.

MAN: Tomorrow.

MOTHER: He said, tomorrow.

You’ve lost weight, I said.

They didn’t give us anything to eat, he said.

SCENE NINETEEN

MOTHER: I went into the classroom to tell the teacher I needed to take the child home. There were a lot of children in the classroom. It was beyond comprehension why there were so many children when there had been a war, why people wanted children when they knew what fate would be waiting for them. Perhaps that was the point, that they wanted new people to live through all the suffering the parents themselves had had to live through, that it would make the weight feel less heavy knowing their children wouldn’t have it any different than they did. Why, asked the teacher, why do I want to take the child home, and I said, but in a way the child wouldn’t hear. Her father is home. He’s home, she asked, incapable of lowering her voice, the old teachers, well, they were gone, and the new ones were just like this one. Hasn’t he died, she asked. Looks like he hasn’t, I told her. Who’s home, the child asked then. Come along, I told her. Come and take a look.

GIRL: I know who’s home, I know.

MOTHER: She said, I know because he never said goodbye.

GIRL: I know it’s Daddy, where’s Daddy, where is he.

MOTHER: He’s waiting outside in the school yard. Then the little one began to run and darted out of the school, Daddy, Daddy, I knew you’d come back, Daddy, Daddy, Daddy, and her tears flowed down her cheeks, and from her cheeks onto the school yard, then onto her father. Littly-Annie, said her father and picked her up, here I am, see, I’ve come back. I knew, the girl said, I just knew, I knew it wasn’t you in the cemetery, that man couldn’t be you. The way he smelled just couldn’t be my daddy’s smell. I never forgot your smell, ever, my nose can remember. And the man couldn’t stop kissing the tear-soaked face and the little girl couldn’t stop kissing the tear-soaked face, for by that time my husband’s tears had also began to flow.

MAN: You too, come here, let’s be together again, the three of us.

MOTHER: When he said that, I went up to them, because when someone says this, you have to go to them, and I went. He didn’t see how difficult it was for me to go to him, because for me he was no more, and when someone is no more, you can’t simply undo this. If I had known that he was alive somewhere and it was only a matter of waiting, then yes, you know he’s alive and won’t erase his memory, but I had to erase it after the telegram came, a hero’s death, with the body in tow, afterwards he stopped existing for me. And I had to think up a way to carry on living, and this was only possible if he stopped existing for me, in my head and in my heart. And now, here he was, the person who was no longer. The feeling I should have had was, he’s here, but by that time he had stopped existing for me at all. A stranger, though I had to treat him as if he weren’t a stranger, even though he was exactly that, his hand was unfamiliar, his face and the rest of his body. It was in vain that I recognised in him the man that used to be my husband, this man could never be that, because my own husband had died, we buried him, I had built my life above me, and now I was unable to give part of it to this man.

SCENE TWENTY-TWO

MOTHER: Go to bed now, he said, and the child said, not again. You have to sleep every night, he said, and I knew once she was in bed, we had to do it again, and I really didn’t want to, but didn’t dare to tell him I didn’t want to, because it was something I had to want. And he started off again, taking the clothes off himself and me, carrying me into the bed, he was very strong again, he had nourished himself back to strength on homemade foods. I, on the contrary, was very light with all the weight I’d been losing, because it was like this, what was happening to me had made me unable to eat. He caressed me where he always did, his hand was cold, all I could feel was this cold hand, a dead hand, then he lay on his side and helped with his hand so that he could push it into me, and he entered me, there wasn’t any moistness, I was unable to produce any, so as it went inside me, it got stuck to the skin and as this skin slipped off him as he pushed inside, the pain shot up in me like fire, but I didn’t want him to know because this wasn’t something you were supposed to reveal. He told me how good it was for him to be with me, how many times he had thought about this while he was away from home, at times not knowing if he would be able to come home at all, when his foreign captors withheld the opportunity from him to write a postcard home, saying only, if nothing else, that he was alive and would come home one day, to experience all this goodness that he’s experiencing with me. How they went hungry and froze, because there was no food and no heating in the barracks, forcing them to huddle together like animals to keep one another warm as much as they could, and when someone stopped warming the others and had gone completely cold, they scooped him out from their midst onto the ground. He talked and pushed himself further inside me, so he could at last warm himself on my supple body after those freezing times, he said supple and soft, although every muscle in my body was taut so I could support the corpse, the dead man’s mass, but for him, compared to whatever he had experienced in that foreign country, everything was soft and supple.

After a while he stopped talking, so engrossed was he in doing it. I knew how long it would last. In the first couple of days, it wasn’t longer than a minute before his pleasure rose, but then he started up again and managed to do it twice, then it was longer. Now it was exactly as long as it had been before he left, no, in fact it was shorter, because the dry vagina held his body tighter, and as his joy peaked quicker, it also ended sooner. I knew the exact stage he was at. Eyes bulging, he was in the grip of one sensation, a thin line of saliva emerged from the corner of his lips, and even his face muscles were relaxed when I reached under the pillow. I had made sure to put it there the day before. It was what we always used for slaughtering pigs, very sharp, almost like a military dagger. A moment before his pleasure consumed him, I summoned all my strength.

I’m amazed now how I had so much strength, having barely eaten for months, but sometimes your inner willpower activates strengths that are not inside you but come from some outside space. And I stabbed him from behind, first through the skin, then through the back muscles, through his lungs and heart, something crunched, I may well have hit a bone. His eyes stayed that way, bulging, his saliva continued to flow, but the movement had stopped as he couldn’t comprehend what was happening to him, he hadn’t felt me stab him, for he was in the throes of an entirely different sensation.

His body fell onto me, that huge weight, his weight, and all my great strength that was in me at that moment left me, he pushed the air out of me as you push cream out of a tube, leaving me lying flat and lifeless under him. I don’t remember how long had passed, when morning had come, I only remember the child shouting, Mummy, Mummy. I woke to find her shaking my hand, Mummy, what’s happened to Daddy, what’s happened?

GIRL: Mummy! Mummy!

MOTHER: She stared at the blood-soaked body and the blood-soaked bedclothes, then ran out of the house and when she came back, the neighbour man came with her, and he rolled the man, who was now completely cold, off me. I was naked, the neighbour man covered me up. Unable to say anything at all, he just stared at me, just stared, as you look at a stranger, I had ceased to be his neighbour. He was unable to say what had happened. Mummy, Mummy, the child sobbed, but I could say nothing. What’s happened to Daddy, she asked. He came home, I said, to say goodbye to you. And now, she asked.

GIRL: And what’s happening now?

MOTHER: Now he’s gone back again, I said.