VOLDEMAR ARKADIEVICH: The production’s director, who also plays the role of the older Stalin.

SERGEI KARYAKIN: Plays the role of Vladimir Lenin.

ANNA KRYLATAYA: The personal assistant of VOLDEMAR ARKADIEVICH, who plays the role of Valentina, the nurse to the older Stalin, as well as the mother of the young Stalin.

TERENTII GRIBS: The playwright, who plays the role of comrade Stalin’s doctor.

GIYA RKATSITELI: Plays the role of Lavrentyi Beria and the primary guard of comrade Stalin.

ALEKSEI BALABANOV: Plays the role of Nikita Khrushchev and the secondary guard of comrade Stalin.

MAN FROM THE MINISTRY: Man who is compelled to play the role of comrade Stalin’s second doctor.

VLADIMIR KUDRAVTSEV: Plays the role of the young Stalin.

MEMBERS OF THE POLITBURO, JOURNALISTS

The MINISTER OF CULTURE, in the form of two telegrams.

The PRESIDENT, in the form of a cough above the stage.

A major theatre company in Russia decides to stage a bold new play about Stalin. The roles are cast, the set is constructed, and a preview for the press is arranged. However, it turns out that one of the viewers at the preview is the President of the Russian Federation: “I’m curious to see how they’re planning to represent my predecessor.” The play begins with Stalin on his death bed, surrounded by doctors and cabinet ministers; the mood is somber and reverential. However, the action segues into a playful fantasy, wherein Stalin rises, Lenin appears, and the two reminisce wistfully about the halcyon days of the Bolshevik Revolution. Afterward, the theater company is informed that the President wants changes made to the script: concerning Comrade Stalin, there can be no humor, and there can be no death. “It’s not by chance,” he explains, “that human beings have two eyes. With one eye it’s necessary to see the tyrant and butcher, and with the other—the mighty builder of the state.” While the playwright is resistant at first, he is compelled by the director—who also plays the role of Stalin—to dramatize the moment when the real Stalin is born.

SCENE 7: THE BIRTH OF A MONSTER FROM THE SPIRIT OF A CHICKEN

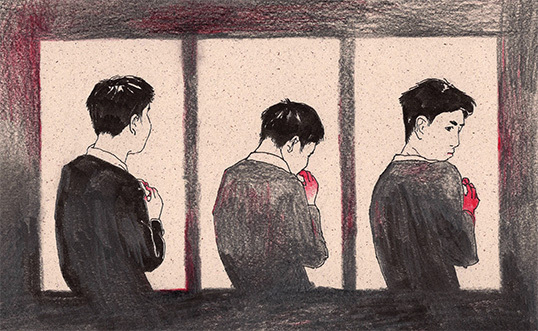

Rehearsal of the first scene of the revised play. ANNA KRYLATAYA is playing STALIN’S MOTHER; VLADIMIR KUDRAVTSEV is playing the YOUNG STALIN. The other actors are observing. VOLDEMAR ARKADIEVICH, who usually plays the role of the OLDER STALIN, is the DIRECTOR; he is smoking a pipe.

YOUNG STALIN: How is your health, Mom?

VALENTINA: Joey, eat the chicken more slowly . . .

STALIN (to TERENTII): It’s a brilliant script. Simply brilliant.

TERENTII: Why are you . . .

STALIN: You’re not a theater worker. You’re a writer. You have no clue how much there is in those phrases. But you’ve got us. Give thanks that you’ve got us.

TERENTII: Thanks.

STALIN: You see, right there. It’s just a single “thanks”—but it’s got irony and hopelessness, bright faith in me and a deep lack of faith in me as well . . . And that’s just one word, Terentii. What’s that look? Oh, these authors . . . They don’t understand anything. They write ingenious stuff, like these phrases here, and don’t even realize it. They write a bunch of crap and make a big fuss about it . . . Just like you were making a fuss about the scenes that we performed yesterday. What was in them, really? A lot of giggles and winks. You just watch, how we flesh out your script right now. Watch the magic happen, Terentii. (To the YOUNG STALIN.) Eat the chicken, but eat it like the monster who will devour people in the future . . . Yes! It’s already better! Imaginary fangs! I don’t see the imaginary fangs, Volodya! Yes . . . Yes . . . They’re growing . . . Oh my god . . . Incomparable . . .

YOUNG STALIN (to VALENTINA): How is your health?

STALIN: No! No! My dear Volodya . . . Deliver it, so that we hear something entirely different in that question . . . This creature is dreaming about plunging everyone into the flames of hell, my dear Volodya! Even his mother, especially his mother, we know this from the archival material that Terentii obtained . . .

TERENTII: I didn’t obtain—

STALIN (blowing smoke into TERENTII’s face and addressing Volodya.): Say, “How is your health?”—so that underneath it we hear: “When, oh when, are you going to die, you old hag?”

YOUNG STALIN: When, oh when, are you going to . . . Oy, forgive me . . . How is your health?

STALIN: That’s better. But do it like this: “How is”—that’s the first lick of the flame, and “your health”—that’s already a roar, the roar of hell fires . . . Try it, Volodya . . .

YOUNG STALIN: How is your health?

BERLA and KHRUSHCHEV applaud.

STALIN (to TERENTII): And that’s just the beginning. In a week’s time he’ll be saying that line in such a way that they’ll put it in textbooks on the history of theatre. Valentina. Let’s go.

VALENTINA: Joey, eat the chicken more slowly . . .

STALIN: Valentina! Are you forgetting that we’re working with a mystical script. (To TERENTII) Yes, yes, mystical. (To VALENTINA) That’s not simply a phrase—“eat the chicken” . . . You’ve already realized that a demon has implanted itself in your son . . .

VALENTINA: But, Voldemar Arkadievich, when did I realize that?

STALIN: A magnificent actor’s question! Your lessons in audacity, Terentii! You realized it this morning. And now you regard that little chicken like a magic potion . . . No, not potion . . . Like magical food. Because you poured into that little chicken all of your love, all of your hope, Valentina! And you are presenting this food to your son with the hope that he will eat it, and the demon will hurl itself out! And you will see your little Joey, your beloved little Joey, as he was before!

VALENTINA: Joey, eat the chicken—

STALIN: A mother’s despair! Invest it with more motherly despair, Valentina!

VALENTINA: Joey, eat the chicken more slowly . . .

STALIN: Break the line into two parts. “Joey, eat the chicken”—that’s full of despair. “More slowly”—that’s full of hope. That your son will be cured, Valentina.

VALENTINA: Joey, eat the chicken more slowly . . .

STALIN: You need to practice it more.

VALENTINA: While for him (pointing at the YOUNG STALIN) it’s immediately “incomparable” . . . (She is on the verge of tears.).

STALIN: Your task is more complicated, Valentina. And it’s about to get even more complicated. Are you ready for it to get even more complicated?

VALENTINA: I’m ready.

STALIN: Deliver that “More slowly” part with the opposite intention. Do you see? In point of fact, you want him to oust the demon more quickly . . . So, deep down “more slowly” to you means “faster, I beg you, faster!” Do you see? Infuse that phrase with the dialectic, Valentina! With the dialectic!

VALENTINA: Joey, eat the chicken more slowly . . .

STALIN: Genius!

BERIA: Isn’t all this too daring, Voldemar Arkadievich?

STALIN: You’ve decided to start joking again, Lavrentyi? You know I’ve got a big joke ready for you.

BERIA: I’m not joking at all. I fear they may suspect that this chicken is actually an eagle . . .

STALIN: That’s bullshit! And even if they do, so what?

BERIA: The symbol of our state . . . Stalin, it turns out, is gorging on the symbol of . . . Voldemar Arkadievich, I’m glad that you’re smiling. But we have to be aware of the risks.

STALIN: You know what, Lavrentyi? I won’t allow anyone—anyone!—to interfere with my self-expression. You may be right. But this scene determines everything; it shows the beginning; here we see how, from out of a young man, a beast begins to hatch, a monster . . . I will not back away from this scene. Not for anything. Even if the police come.

VALENTINA (to BERIA): I understand perfectly well how much you’d like it if I had no role in this production at all.

KHRUSHCHEV: There’s no need to treat Lavrentyi like this. His suspicion is an asset. And if he becomes completely rabid—we’ll shoot him! (Everyone laughs, except STALIN and TERENTII.)

VALENTINA: I know why he’s taking vengeance on me. Voldemar Arkadievich, he solicited me. Drunk, filthy, and depraved—he solicited me.

STALIN: Lavrentyi . . .

BERIA: It’s slander!

VALENTINA: Prove it!

BERIA: How in the world can I prove that I didn’t do something?!

STALIN: Brilliant. Stalinism is in the air, just as we wanted! All right, Lavrentyi, prove you’re innocent! Quickly! Quickly, while I still have faith in you. Well, come on . . . Well . . . ? That’s it. My faith is gone. You’re a traitor, Lavrentyi. You are an enemy. Oh, I’m joking, come on, my god. I have news for you, Lavrentyi and Nikita. There’s nothing bad about it. Artistic news, and it doesn’t have anything to do with morality. Accept it with an open, actorly heart. Khrushchev and Beria will not be in the new production.

VALENTINA: So sad.

BERIA: Josef! I don’t believe . . .

KHRUSHCHEV: Voldemar Arkadievich, this is a tragedy.

STALIN: I understand.

KHRUSHCHEV: How we dreamed about these roles . . .

STALIN (with a heightened intonation): A theatre is an empire. What is one little actor’s fate in comparison to the fate of a whole theatre? The decision has been made. Your talents will be needed in the future. Now is not the time. (To the YOUNG STALIN and VALENTINA) And so, young Josef, my dear Keke, let’s not be distracted, we’re moving on (to KHRUSHCHEV and BERIA), and you two go out into the auditorium . . .

YOUNG STALIN: How is your health, Mom?

VALENTINA: Joey, eat the chicken more slowly . . .

BERIA and KHRUSHCHEV exit.

SCENE 8: THE KITES OF STALINISM AND THE FALCONS OF LIBERALISM

BERIA: Try to eat the chicken . . .

KHRUSHCHEV: How is your health?

(They laugh somberly.)

BERIA (mimicking Voldemar Arkadievich): The empire doesn’t need you, the theatre’s fate is more important than your fates . . . Does he think that he’s an empire? That he’s the theatre?

KHRUSHCHEV: It’s a tragedy, a tragedy . . .

BERIA: The theatre is dying, Nikita. Now this is clear, as well as the fact we will not be in the new production.

KHRUSHCHEV: It’s so painful . . . I can’t believe it.

BERIA: And now what? Are we going to sit amongst the audience at the premiere? Applaud and swallow our tears? Is that what we worked two years for? I’m terrified.

KHRUSHCHEV: Of what?

BERIA: I’m afraid of my own thoughts, Nikita.

KHRUSHCHEV: Let them out.

BERIA: Voldemar is pushing the empire into an abyss.

KHRUSHCHEV: It’s a tragedy.

BERIA: You and I, Nikita, are the Himalayas . . . And all these little actors . . . They fawn over him, if only to save their little roles.

KHRUSHCHEV: It’s disgusting to watch.

BERIA: You know what I call the style that Voldemar is prepared to work in? And, by the way, he’s been working like this for a long time. Out of fear. “Not-a-candle-for-God-not-a-deal-for-the-devil.” Or—“no-way-ism.” It’s a very contemporary style, by the way, for those who want to save themselves. Voldemar has already directed productions like that, where he kept himself aloof. But this one is especially dangerous, Nikita.

KHRUSHCHEV: Especially dangerous, Lavrentyi.

BERIA: You know what this premiere is going to be? It’ll be the premiere of the outstanding instinct for self-preservation of Voldemar Arkadievich. To participate in all of that—it’s disgusting. It’s vile.

KHRUSHCHEV: Really?

BERIA: Our emperor has lost his senses. I was seeing it already yesterday, when the shocks from the telegrams began. The illness spread more quickly than I thought it would. But not more quickly than I write. I foresaw it all. (He pulls out of his pocket two sheets of paper.) Here we’ll have your signature too, Nikita. And when Voldemar falls, he won’t drag you and me into the abyss with him! Here are two . . . denunciations. One—to the organization of anti-Stalinists. And the other—to the place where Stalin is revered and adored. Our local Stalin thinks that he’s outsmarted everyone. Thinks that he’ll run between the streams of Stalinism and anti-Stalinism, to oblige both our people and their people! To pass off silence as opinion, alarm as objectivity, terror as neutrality, and a creative impasse as deep thought! But these little denunciations . . . They will change the optics, bring things into sharper focus. Reveal the weak spots—for both the Stalinists and the liberals. (In ecstasy.) The kites of Stalinism and the falcons of liberalism will descend upon Voldemar! And we will stand aside, while they gnaw on his little bones. Stand there and whisper in his ears: Are you in pain, Voldemar Arkadievich? It looks like they’re pecking out your eyes? Ah, already? And what now (shaking his head.) Your spleen— So sad . . . Well? Are you with me?

KHRUSHCHEV: Unh-uh. I’m outta here.

BERIA: After all that we’ve said?

KHRUSHCHEV: I was only listening, Lavrentyi.

BERIA: But your signature? Your signature? You will perish! Alongside him! You fool, with what they did to your role . . . You fool!

KHRUSHCHEV exits. BERIA rushes after him.

SCENE 9: OR MAYBE I’LL SHOOT YOU ALL IN THE DINING HALL?

TERENTII: I understand that theatre involves compromise. I’m not proposing that we stage the whole play, in full, I’m not stupid, and I understand that they’re pressuring you—

STALIN: You are mistaken, Terentii. You’re just like a child. Pressuring . . . Who can put pressure on Voldemar? Do you know what principle should be adhered to? Think before you speak. Those who do the opposite have lives that are troubled, short, and sad.

TERENTII: Okay! They’re not pressuring you.

STALIN: That’s right, Terentii.

TERENTII: But to not stage even twenty percent of the script?! At least do half of it. Otherwise, the tone is lost, the whole idea is lost, and I don’t understand anymore who the play is about, who exactly is your . . . our Stalin, what we came together for, I don’t understand . . . To tremble with fear and show everyone how scared we are? Of a ruler who died long ago?

STALIN: You’re still like a child. That’s bad. Because you are not a child.

TERENTII: Voldemar . . .

STALIN: Do you know how much our Nikita is suffering? Just now, he was hitting his head on the board with the cast list. Didn’t see his name there and started to hit it. He broke the board. He broke his head. (He pulls out a piece of paper and shows it to TERENTII.) The cast list. With Nikita’s blood. Take it.

TERENTII: What for?

STALIN: So that you experience drama. Real, not imaginary, drama. Nikita had a fit, they called an ambulance. He suspected that he’d been insulted. But all the same he stayed in the theatre. Tied a shawl around his head and stayed. I hope, he says, to fulfill my obligation as an actor and a citizen. It’s like that, Terentii. Have you heard how he sings? Write him a tiny little role, so that our injured man can sing from the stage.

TERENTII: What kind of role could he sing . . .

STALIN: Suddenly, somewhere in a forest glen, an unexpected singer delights the ear of the future dictator . . . You can dream up better than I can where he could sing; I’m not your advisor on this one, you have complete control. Just save Nikita.

TERENTII (shrugging his shoulders): Then we’ll have to save BERIA too.

STALIN: Oh, no! He’s a traitor. (Quietly.) He’s in a cell now.

TERENTII: Wh- what?!

STALIN: Nikita suggested it! As a joke at first, but then everyone got carried away . . . Nikita most of all: “absolutely,” he shouted, “lock him up in chains” (he laughs). We have a little room here, the dressing room of an actor who died long ago, there’s no heat. Lavrentyi is cooling off there now. Howling. But what’s to be done? Otherwise, God only knows what he’d spread around the city before the premiere. So Nikita must be rewarded. Let him sing. He has served us well.

TERENTII: But the cell—is that a joke?

STALIN: You don’t need anything on the fifth floor, do you?

TERENTII: What would I need there?

STALIN: Then it’s a joke. (TERENTII rises up to leave.) Think about Nikita, think about our singer. About the actor and the citizen! (TERENTII exits, Voldemar Arkadievich sings with a slight Georgian accent.) Where are you, my Suliko . . . (He puts on the white jacket of the generalissimo, starts to smoke his pipe.) Around me are don-keys, goats, and shrews. And no one at all—to talk to. (Getting into character, he speaks in a heightened tone.) Around me are donkeys, goats, and shrews. And no one at all to talk to. I am alone, like the Lord himself. Surrounded by traitors. Each with a knife behind his back. Do they know how hard it is to be an emperor?