In Krzysztof Penderecki’s 1961 composition, Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima, the listener’s anticipation rises, ironically, as the thin strings slowly dwindle into silence before, at around the four-minute mark, they abruptly return in a resounding, dissonant wail suggesting the detonation of the atomic bomb. The reader of The End of August, which follows its characters through World War II, will surely be expecting the same moment, but may be unsettled by Yu Miri’s understated presentation of it despite how this cataclysmic moment in Japanese history drastically changed the course of events in places like Korea, as well. The breakdown in communications during wartime and the stream of unbelievable news from unreliable sources render the event, as heard by Koreans, unintelligible, as whispers from another land. The chorus of townspeople in Miryang, where most of the novel takes place, is standing before the statue of a Korean hero, debating the meaning of its seemingly miraculous sweating, when somebody says:

“ . . . Yasuda said that they dropped some new kind of bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

“A new kind of bomb?”

“You don’t know what kind?”

“No idea. Even the papers have only occasionally been getting through since April, you know.”

A few lines later, someone expresses a fear that this “new kind of bomb” might be dropped on Korea, but the conversation—and any further mention of the atomic bomb—is interrupted by distant sounds of celebration at the imminent end of Japan’s thirty-five-year occupation of Korea. Despite the fleeting mention, the knowledge that such world-changing events are happening elsewhere, and having profound effects here, is part of what it means to know that one is in a pivotal moment in time. Likewise, ‘The End of August’ is an incredibly rewarding novel that continually ignites the dizzying, terrifying feel of living in the flow of history.

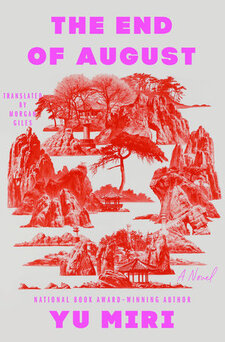

Born and raised in Japan, but with Korean heritage, Yu Miri is considered a major zainichi writer, working also as a playwright, radio host, and bookstore owner. She began serializing The End of August in 2002 and published the complete version in 2004. Tokyo Ueno Station (2014, English translation also by Morgan Giles, published in 2019), which won the National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2020, considerably raised her profile in the English-speaking world. Tokyo Ueno Station also showed off her diligent efforts in researching the subject matter of her novels: she spent time with the homeless population in Ueno Park in central Tokyo and collected stories of the laborers, many of them very poor, who assisted in the cleanup of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. In both novels, Yu Miri reveals herself as a writer with fathomless compassion.

The End of August is a historical novel—but written as the genre’s first cousin, the family saga—which follows the ramifications of a historical process across generations. The novel is based on the life of Yu Miri’s grandfather Lee Woo-cheol and spans about fifty years, ending (and beginning) with the author taking up a role as a character in the novel, committing herself to this story. Woo-cheol’s world is one of bitter luck. He comes from a family that has suffered the deaths of several children and a nation under the control of the Japanese Empire. His language and culture are increasingly restricted (for instance, in 1940 Japan outlawed the use of Korean names, forcing Koreans to adopt Japanese names), deeply damaging his sense of national and personal pride. Many young men have left to join the anti-Japanese resistance in China, and the families they have left behind live under constant police surveillance. Woo-cheol’s one real talent and outlet is long-distance running, and those around him repeatedly say that the great tragedy of his life is the cancellation of the Tokyo Olympics of 1940 (due to Japan’s invasion of China in 1937), where he was likely to compete. We follow Woo-cheol as he runs through the joys of adolescence and early love, the deaths of family, the breakdown of one marriage and the establishment of another, the horrors of World War II, the disappearance of his younger brother Woo-gun during the brutally authoritarian and anti-communist regime of Rhee Singman, and his later life running a pachinko parlor (this novel shares several themes with Min Jin Lee’s 2017 Pachinko). Woo-cheol is a complex figure who cares for his family, even as he abandons his first wife during periods of grief and hardship. He strives to become the pride of Korea as a runner, but escapes to Japan to avoid being drafted into the war effort (a flight that Woo-gun refuses to join him on). As much as the novel admires the sport of running (at the beginning, Yu Miri, as a character in the book, completes a grueling marathon in South Korea), Woo-cheol is, as often as not, shown running away from the tragedies that beset him.

The literary family saga has often been centered around the aristocracy (think of di Lampedusa’s The Leopard, or Roth’s The Radetzky March), as this was the type of family structure specifically meant to last across generations. The aristocratic family could survive anchored onto “the estate” as the last place of refuge against a wave of social change. The Lee family is certainly not that. Yong-ha, Woo-cheol’s father, is a traveling fortune-teller before settling in Miryang to run a shop that sells rubber boots. They are in no sense shielded from the deprivations and injustices of their time. But they are not enlisted by the author, as often happens in the family saga, to act as a synecdoche for the national body, or symbol of the Korean spirit—they survive, but with a question mark over what, exactly, has survived of the Lee family. Yu Miri also takes up the viewpoint of individuals who have vanishingly fleeting relationships with the Lee family: Yong-ha’s mistress and her daughter; the Japanese midwife at Woo-gun’s birth; a young neighbor named Eiko who is sold to the Japanese military as a “comfort woman”; and a sister of the anti-Japanese insurgent Kim Won-bong. The narrative even, on occasion, is that of Arang, the ghost of a legendary figure in Miryang, bearing witness to the misfortunes of the Lee family:

“The smell rising from the young man’s body drifted past Arang’s face. She cast her eyes around. Droplets of sweat were splattered on the ground, but this wasn’t the smell of sweat. Blood. His right leg was wet with bright red blood. Aigo, ireolsuga! Arang bent her neck like a wilting flower and with her own eyes, immobilized by grief, she saw the bullet hole. I can’t stop it, I can’t stop anything . . .”

The End of August is written with a healthy modernist skepticism of unity, continually undoing the boundaries of the family, nation, and the historical epoch that are its subject matter. It is ambitious not simply in its historical scope but also in its stylistic and linguistic eclecticism: first-person narration may quickly shift to third-person and back again; previously named characters might be referred to in the abstract, such as “the man” or “the woman,” at certain points. The novel is bookended by passages, written as dramatic scripts, where the character of Yu Miri employs the services of mudangs (Korean religious practitioners akin to shamans) to communicate with the spirits of her family. Narrative threads are also repeated throughout the novel. Eiko’s story of being made a “comfort woman”, for example, is related three times: first as a vague tale told by a ghost during the aforementioned séance; then the agonizing narrative, as Eiko experiences it, in the middle of the novel and substantiated by Yu Miri’s own research; finally, Eiko telling her story to Woo-cheol as they return to Korea after the war. While the details of each retelling are essentially the same, Yu Miri has a remarkable ability to drastically shift the feeling of each.

A historical period in The End of August is as much a continuum of sensual experiences as it is a series of interconnected events. This is especially true in the feel of the characters listening to the world around them. Few novels make as much use of onomatopoeic language, and the characters are surrounded by the sounds of cicadas humming in the sunset, the wind racing through a valley, the splashing of the waves on a ship heading home, the moans of people having sex in another room and, significantly, the sound of a language you don’t understand. The novel was written in Japanese, but Korean words and phrases (as well as, occasionally, Mandarin) are left mostly untranslated. Context and repetition may serve to provide a meaning or, at least, a general sense (ceremonial invocations, expressions of distress, and so forth) of the language for the nonspeaker. The text celebrates the interplay between the familiar and unfamiliar, and—keeping in mind that this was originally written in the language of the empire that controlled Korea for decades—the reader is confronted with the distance and intimacy of a world that is not one’s own. In one telling scene, a Japanese midwife, who has been invited to Woo-gun’s first birthday for her assistance in his birth, is struggling to follow the flow of conversation. This episode recalls a moment early in the novel where Yu Miri admits that she also has a limited understanding of Korean but is simultaneously drawn to and daunted by it. Korean is the language that the author can’t speak, but also can’t help but speak. It’s a testament to the discernment and trust of Morgan Giles’s translation that what the story might lose in the sense of strict meaning, it gains in the sensation of being in a rich, multilingual atmosphere.

Between the hum of the natural world and partially understood languages, between the internal contemplations of the silent runner and the segments of reportage detailing the news and politics of the time, Yu Miri detects the shocks of Korea’s twentieth century in the deep and wild psychology of her characters. But she does so without falling into the trap of treating her characters as allegorical figures for the nation’s history, instead developing them as flowing into and out of each other’s lives in a widening body of experience. Much of the narration is from somebody who is currently running and, in place of punctuation, the phrase “in-hale, ex-hale” occurs throughout the novel. This choice acts as a meditation amongst the currents of thought, and I get the sense when reading it that Yu Miri is aiming toward an impossible sound that eludes even the phonetics of written language itself. It creates a momentary, quiet peace before the gears of history start grinding again.