It was not until 1993 that a bride was legally required to give consent to marriage, and that fathers were banned from forcing daughters to wed. In 2004, women were finally given the right to appeal for divorce. Despite this legal right, many women, including the wife in Tahar Ben Jelloun’s novel The Happy Marriage, do not feel capable of shouldering the burden of legal separation, however much it may be desired.

Dealing with societal patriarchy in microcosm—within a single relationship—The Happy Marriage explores the abuses of power between spouses, and the double standards maintained by a society that upholds the unequal treatment of men and women. First published in French in 2012, the novel captures the contemporary struggle between deep-rooted sexism and a surge in women’s liberation in North Africa. While Moroccan women have experienced a degree of emancipation in recent years, the fight for equal rights is far from over.

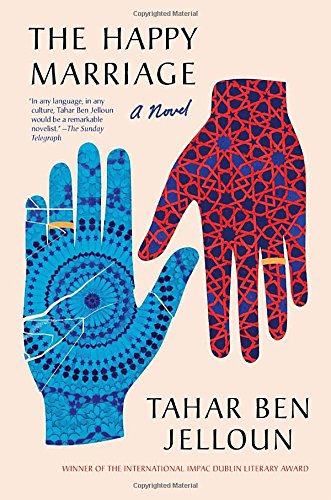

Ben Jelloun is one of Morocco’s most celebrated and translated writers. He has won the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and the Prix Goncourt, and he is regularly named a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 2008, he received France’s Cross of Grand Officer of the Légion d’honneur. He is author of over twenty works of prose, poetry, and fiction, including The Sand Child (1985), The Sacred Night (1987), The Fruits of Hard Work (1996), and This Blinding Absence of Light (2000).

Ben Jelloun was born to working-class parents in Fez, Morocco in 1944. After enrolling in a Franco-Arab school at the age of seven, he moved to France at twenty-six to study at the Sorbonne. He writes exclusively in French, claiming in an interview with The Paris Review that, for him, Arabic “is a sacred language, given by God in the shape of the Koran, it is intimidating . . . It is inhibitive; one would feel almost guilty manipulating it . . . There are things I could not [deal] with in Arabic, for example, sexuality or criticizing the religious behaviour of certain characters.” Translated skillfully and consistently into English by poet and critic André Naffis-Sahely, The Happy Marriage demonstrates that French may be the language of love, but also of despair, loathing, and even hate.

Opening the novel with a quotation from Ingmar Bergman’s ode to separation, Scenes From a Marriage, Ben Jelloun offers no doubt about the irony of his book’s title. Bergman’s work becomes a recurring motif, accompanied by allusions to Fritz Lang, Jean Genet, Francis Bacon, and Luis Buñuel. Like the couple in Bergman’s work, the man and woman at the center of The Happy Marriage can neither stand nor stay away from one another; the line between love and hate is all but invisible.

Their relationship is complicated by a class difference strongly disapproved of by the husband’s wealthy, educated family, who regularly treat the wife’s rural tribe with poorly disguised disdain. Thus, the wife faces two innate challenges—she is not only a woman, but also poor: a twofold second-class citizen. However, in this exploration of marital disharmony, Ben Jelloun does not limit himself to representing the physical and statuary supremacy of men, although that comes first; the novel also examines how women can exert power over men, even as they are oppressed and debased by them. He deftly toys with our assumptions about and allegiances to the narrators, manipulating the reader as skillfully as his characters manipulate one another.

Thematically, this novel has much in common with Ben Jelloun’s earlier work, which often comments on the socio-economic and religious status of women, particularly Muslim women. Perhaps best known is the trilogy—The Sand Child, The Sacred Night, and The Wrong Night—centering on Zahra, a girl raised as a boy by a father desperate for a male heir. His first novel, Harrouda, addresses, in part, the demonization of sex workers, but also the opportunity to denounce patriarchal control through female empowerment.

The Happy Marriage divides unexpectedly into two parts, unannounced by a table of contents. The first is narrated from the husband’s point of view, the second from the wife’s. This formal distinction denotes the disparate techniques of recollection and record-taking used by each spouse; while the husband’s account is meticulous and precise, his wife’s is less linear, marked clearly by her emotions. Naffis-Sahely’s translational style is versatile, capturing that emotion in English equally as well as it captures the directness and precision of the novel’s first part.

We meet the husband, referred to as “the painter,” in Casablanca in early February of 2000. Disabled by a stroke six months earlier, he is almost completely paralyzed. Impotent, claustrophobic, and unable to paint, he is entirely reliant on others for assistance. Ben Jelloun’s representation of his struggle is evocative of Jean-Dominique Bauby’s memoir The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, composed as it was while the author was suffering from locked-in syndrome. Bauby captured in painstaking detail what life is like for someone trapped inside their own body, unable to communicate, and worse still, denied the creative power they once had. Ben Jelloun’s painter:

had a close brush with death, but he hadn’t completed his work. He took this as an insult, a dirty trick that fate had played on him, and a spiteful one at that. The narrative evokes warmth and sympathy for this man, and admiration for his strength in the face of such adversity. In contrast, his wife is presented as unfeeling, even malicious; readers learn that she has not visited him since the stroke, and “hadn’t shown the slightest interest in looking after an old sick man.” Ben Jelloun’s depiction of the painter’s disability is moving, but manipulative. It is soon apparent that the disparate cultural and economic backgrounds of the husband and wife are an unavoidable source of conflict. He believes her to be uncultured and crude; in retrospect, he reflects, “one had to be absolutely crazy to bring such different worlds together.” As we read on, we learn of his adultery, and our dislike for him grows:

To avoid bickering with her, he’d begun to flee the house to have secret rendezvous with more loving women, women who admired him both as an artist as well as a man. He found a great deal of comfort with those women and a kind of sweetness that he really needed. Readers begin to suspect the validity of the painter’s claims, questioning the extent to which his wife is being misrepresented. This extent is revealed in the second section, if we are to believe the painter’s wife, whose response comprises the novel’s latter part.

Composed as a response to a written manuscript discovered in her husband’s safe, the novel’s second section is directed at the reader and written in the first person, unlike the painter’s, which is written in the third person and presented—however misleadingly—as an objective recollection. We learn that the painter’s account is a ghostwritten memoir, which accounts for its detached, yet biased, tone. Upon finding the manuscript, the wife feels driven to give her side of events, and offer the "facts" about their relationship.

The beginning of her narration marks the first occurrence of her name: Amina. In response to this erasure of her identity, she disparagingly refers to her husband as “Foulane,” an Arabic word meaning “any old guy.” She criticizes the title of his memoir, “The Man Who Loved Women Too Much,” as a shameless rip off of Françoise Truffaut’s The Man Who Loved Women, dismissing the ghostwriter’s talents, and the text’s accuracy. Unlike the ghostwriter, Amina writes with immediacy and passion, offering intimacy and inviting our allegiance.

Raised in a deprived rural village ruled by an oppressive patriarchal structure, Amina had to fight for freedom and independence: “There were no trees or plants where I grew up. But there were animals and men. Wretched animals and women resigned to their fate. I rebelled against all that.” While still a child, she was informally adopted by a wealthy French couple, and offered a chance to break free. After the couple divorced she rejoined her family, but found they had little left in common, and so was filled with a great sense of alienation that follows her through adulthood. She feels violated by her husband’s adultery, reflecting that “[b]etrayal is a terrible thing, an unbearable humiliation. Just unacceptable.” Although their marriage was happy for several years, Amina believes this “fairy tale” arose from the sort of “romantic love [that is] a fiction invented by novelists.” From the very start, they lied to each other and to themselves about their compatibility; with hindsight, both realize such a relationship was doomed to fail.

Amina describes her husband as, “an Ayatollah in Western clothes,” his modern, liberal appearance disguising traditional sexist Islamic values. Although Moroccan culture does not actively encourage extra-marital adultery, men are treated with far more lenience for such behaviour. Amina points out that:

My morals, ethics and upbringing forbade me from cheating on him. In our culture, a woman who cheats on her husband no longer has any rights, everyone thinks badly of her, even if she was victimized by a lying, violent husband. This double standard prevents her from seeking out pleasure, retribution, or even comfort from another man.

So her revenge must take a different form. With the painter incapacitated, Amina decides that her best chance at retribution is to exert her newfound power over him, gleefully informing us, “[h]e needs me whenever he needs to sit, eat, stand up, or even shit. He’s at my mercy.”

It is traditional for stories of lovers from conflicting backgrounds to end with love overcoming adversity. In The Happy Marriage, however, love conquers naught. Both partners are left miserable and alone. At one point, the painter asks, “Why should anyone pay so dearly for having fallen out of love?” But Amina’s punishment arises from staying in love:

I can safely say I was only ever spurred by love. Not just any kind of love. The sort of love that had neither rhyme nor reason to it. Something different. I loved him because I had no other choice. One is sentenced for a loss of love, the other for maintaining it. Such vastly different perspectives, and such dissimilar experiences of suffering within the same relationship give The Happy Marriage a certain universality. It will be recognisable and relatable for anyone ever lucky enough—or unlucky enough—to be in love.