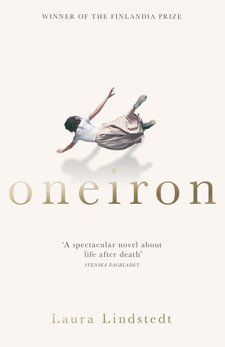

Up until then, the reception of the novel had been mostly celebratory: newspapers called it “close to perfection” and “remarkably bright even on an international scale,” and admired its skilful execution. In Oneiron, seven women from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds arrive in an empty white space, which they gradually understand to be some kind of bardo. The women are: Shlomith from New York, Polina from Moscow, Rosa Imaculada from Brazil, Nina from Marseilles, Wlbgis from the Netherlands, Maimuna from Senegal, and Ulrike from Austria. According to the back of the Finnish pocket edition, all seven are held in “a posthumous limbo, / which one cannot escape – except / with the help of words, stories.” Bloggers soon applauded the book for being all about women, and readers pinpointed “feminism” as its “central theme.” In particular, passages on the connections between Judaism and anorexia were thought by reviewers to be, in understated praise, “really good.”

But then Finnish journalist Koko Hubara wrote a blog post criticising Oneiron for cultural appropriation. Citing her own Jewish upbringing and experience of eating disorders, Hubara identified the novel’s treatment of these subjects as deeply derogatory. In asking why Lindstedt couldn’t instead write from the perspective of an Evangelical Lutheran, ethnic Finn, Hubara wanted to discuss the limits and definitions of cultural appropriation in Finnish literature and public discourse. Hubara’s critique received an immediate and aggressive backlash from the public. She wrote again, clarifying that she wasn’t advocating for the curtailment of creative freedom, but rather trying to open a conversation about the racial dimensions of the relationship between this white author and her black and brown characters. But many Finnish readers wouldn’t have it, once more flocking to social media, writing on Reddit about this domestic example of “PC gone mad.”

In Oneiron, the women and their life stories are filtered through an omniscient narrator, who treats her subjects with occasional sly irony but ultimately allows each of the women to bend the narrative into a genre and form apparently suited to her personality and proclivities: a dramatic script for the telenovela-loving Rosa Imaculada with her “Latin-American temperament,” while the alcoholic, bookish Polina delivers a sophisticated lecture on the mystic Swedenborg’s theories of hell and existence because, like her fellow Russian Tolstoy, she is soulfully concerned with life and death. As another Finnish commentator, Silvia Hosseini, observes in Nuori Voima, Oneiron draws heavily from racial and cultural stereotypes. Nevertheless, the novel’s cast of characters is the most international troupe to be found on the Finnish literature scene. As readers unwilling to problematise the novel’s bothersome relationship with race very swiftly point out, there is representation here. Certainly, perceptive, informed conversations about cultural appropriation, anti-Semitism, and racial stereotyping are needed not only around Oneiron, but in the public arena in Finland more broadly. It just so happens, as Hubara notes in her initial blog post on Oneiron, that Finnish does not yet have all the necessary vocabulary for such a conversation—there is, for example, no standardised wording for “cultural appropriation.”

*

The novel’s inclusion of an untranslated letter in Hebrew might appear to offer a riposte to accusations of cultural appropriation; for the reader with no Hebrew skills, the letter perhaps suggests privacy at the heart of Shlomith’s Jewish experience. This impression, though, lasts only for fifty pages or so, until a full translation of the letter is presented as part of a lecture Shlomith gives. As Koko Hubara points out, this awkwardly suggests that, for all its Jewish content, the novel does not imagine itself to be read by a Hebrew speaker. This is the most pronounced multilingual gesture in a novel that mottles its narrative with bits and pieces of French, German, Portuguese, Russian, and Dutch according to who is telling her life story, mainly to remind readers of the women’s multilingual posthumous existence and to feed the polyglot reader’s vanity. This multilingual novel therefore settles into its new translated form effortlessly, English being its natural linguistic destination: while the characters converse in Finnish in the original, the assumption is that their lingua franca is in fact English. Owen Witesman is one of the most prolific translators of Finnish into English, and the narrative seems to have flown efficiently from his pen; his skills are especially evident in several delightful applications of dictums and in the way he reproduces Lindstedt’s alliteration, which she often uses to heighten the scene’s humour or, at times, to invoke Kalevalaesque otherworldliness. Lindstedt’s poetic powers are most manifest in passages such as this evocation of the world’s shared stories, for which Witesman provides an English equivalent that both alliterates and manages to retain the original imagery:

Like about how the world was born from an egg, the horse from the sand, the foal from the foam of the sea. The wolf from a coupling of virgin and wind, iron from breasts of motherless nymphs, frost from a serpent that gave suck with no teats. Agony from stones of suffering ground against a mountain of pain. Tumors from a golden ball dragged to shore by the fox. Death from arrows carved from splinters of the World Tree. And Summer Boy brought blood!

In its English shape, Oneiron inevitably loses one of its claims to multilingualism—its passages in English, the foreign language most prevalent in the novel’s original form, are now subsumed into the English whole—but a consonance of several languages still enlivens the novel’s pages by adding colour, though not so much substance.

As delightful as well-thought-out alliterations are, the more challenging part of a translator’s job is probably understanding the cultural surroundings of the original language and imagining a comparable context for the translation that comes to exist in different cultural and linguistic conditions. Oneiron’s relationship with race is difficult to render in any new form, and this challenge may be exemplified by specific vocabulary, which obliges the translator to make tricky choices. In the beginning of Oneiron, Rosa Imaculada is described twice as “mulatti,” which corresponds to the English “mulatto.” Calling her “brown-skinned” instead, Witesman opts to write both of these occasions out, suggesting that the choice is deliberate. Many things might be implied by this particular translation choice, one of which may be cosy censorship of what most of the novel’s English-speaking readers would consider a blatantly racist term. The translation nevertheless reproduces the original assumption of default whiteness: only Rosa’s and Maimuna’s skin colour is detailed. Yet even the Finnish equivalent of “mulatto” is not exactly a perfectly polite term: using it hints that the speaker’s—or the author’s—cultural frame of reference might not be that international or “politically correct.” The translation is attempting to take into account the differing strengths of the word in Finnish and English: while recent Finnish scientific publications appear to denounce the term, a quick Google search pulls up public forum conversations that are ambiguous about it; in contrast, a similar search in English plainly states that the term “mulatto” is out of use. The English vocabulary employable in a discussion of racism, in comparison with Finnish, appears more developed and mature; it is likely that the Finnish word will catch up with its English fellow as it ages.

Another racist term which has yet to go out of use is the Finnish N-word, “neekeri.” The word makes an appearance in Oneiron, in the convenient absence of the two non-white characters, when Polina and Shlomith start citing an old nursery rhyme, the Finnish title of which is given as “Kymmenen pientä neekeripoikaa”—“Ten Little Nigger Boys.” In it, ten boys die one after another in different incidents, such as being executed or eaten by a bear, and the last boy, unable to bear his loneliness, hangs himself. The N-words in English and Finnish seem to have aged at different speeds: one indicator of this is the title of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, which refers to the same rhyme; the book was originally published as Ten Little Niggers in the UK and republished in the US as Ten Little Indians between 1964 and 1986. Meanwhile, it existed in Finnish translation as Kymmenen pientä neekeripoikaa all the way up to 2003. This presents Witesman with another challenge, which he reasonably solves by using a slightly more recent, and slightly less offensive, English version of the same rhyme—a version referring to “Negroes” exists too, but Witesman chooses “Ten Little Indians” instead. The word is repeated in Oneiron when one of the women remarks “We’re all Indians in the face of death,” explaining the reasons for the rhyme’s inclusion. Nevertheless, the point about death as the universal leveller could have been made in other ways too, and in fact, Oneiron does make the point in other ways; there are no legitimate grounds for using the Finnish N-word at all, which makes this scene feel pointlessly provocative, and Witesman’s well-judged translation as “Indian” replicates this instance of poor taste.

Translations of political and social identities and their intersections, then, must relate to whatever contemporary linguistic frameworks they exist in. What Oneiron’s Finnish readers have recognised as its feminism also feels outdated. A number of the characters’ life stories idealise motherhood—which is, for Nina, “the incorruptible core of womanhood”—and essentialist notions of femininity are so persistent that when Wlbgis describes her discomfort in her own body, likening herself to “a transvestite, a lump that had fallen to earth from outer space,” the comparison is unsurprising. One of the most interesting things that Oneiron does is to anticipate political criticism by frequently inscribing in the text its possible animadversions; the novel thus harnesses Andrea Dworkin for a feminist commentary on Shlomith’s anorexia-glorifying performance art. The narrator implies knowledge of the outdatedness of Dworkinian feminism by treating her with irony and humour, but on the other hand, the narrator fails to apply any alternative feminism during a rape scene—which Dworkin, who is often claimed to have argued that all heterosexual intercourse is rape, would have had much to say about—and instead remains horrifyingly disengaged, thus manifesting Oneiron’s difficulty of situating its feminism.

*

Rather like the inclusion of Andrea Dworkin to present/prevent the inevitable questions about the novel’s feminist credentials, time and again the novel seems to acknowledge the prevalence of the racial and cultural stereotypes it leans on. At length, the disconcerting thing is that Oneiron does not really do much, if anything, to undermine or deconstruct those clichés. One reason for this absence of social review may be the elusive narrator; because of the illusion of omniscience, the reader easily comes to assume that the narrator is impartial. This impression is encouraged by the almost complete lack of information about the narrator: only gradually can we decipher the narrator as someone who is stuck in the white space too, but unlike Shlomith and her “afterworldly sisters,” she is unable to depart from it. In addition to irony, the narrator brings something else to the narration: her cultural and linguistic frames of reference. Wittingly or unwittingly, Lindstedt has created a Finnish narrator: Finnish phrases and sayings feature in perspectively neutral moments—stories are shaped like “cinnamon-buns” and “air can be measured in liters, like strawberries or peas”—but also in narrative situations where the focalisation is supposed to be one of the seven women’s. In these slips, the Austrian Ulrike, for example, has surprising knowledge of traditional Scandinavian yard swings or Finnish Santa Claus traditions. In translation, these Finnishisms stand out all the more, because there is no apparent reason for their presence. It is worth remembering then that the women’s stories are not relayed to the reader by a neutral party, but that the narrator’s worldview influences her reproductions of their worlds. As it is, the narrator’s identity is one of the frustrations of Oneiron—overall, it is not the novel’s style to provide its readers with satisfying answers—but it is an interesting lesson in the deceitful attractiveness of omniscient narration.

Koko Hubara’s challenge to Oneiron essentially situates the novel within the debate about who is allowed to speak and about whom; this is also where the novel sees itself. Employing a number of languages and perspectives and playing around with genre and narrative, Oneiron engages with the question of the right to speak. Wlbgis, whom the novel consciously sets up as the boring one, faces an enforced silence: she dies of throat cancer, the disease leaving her not only dead but also mute in the afterlife, and, as the narrator observes, “When Wlbgis lost her ability to speak, she also lost the last of her rights.” In the second part of the novel, when the women begin to transition onward, they begin to communicate telepathically by sharing thoughts, enabling initial verbal exchanges between Wlbgis and the other women. The narrator sarcastically observes the women’s newfound interest in Wlbgis:

they realize suddenly, at the last moment, that she is more valuable than anyone. Not for herself, of course, but as a mirror. There can never be too many mirrors. Not even in these circumstances. Have you enjoyed our company? Traces of narcissism cling tight to a person. How did you like us?

This scene more than any other highlights the women’s unlikability: What kind of a person, one can ask, pressures another, only recently made legible to others, to produce a commentary on them? Through its representative women, Oneiron proposes that we wish the voiceless to gain their voices in order for them to speak about us, not about themselves; as the narrator muses, “Approaching death doesn’t ennoble anyone.”

In the Beckettian quasi-final destination that Oneiron imagines, “everything else is gone, everything except words”: gradually losing their bodily sensations, the women are left only with their languages, voices, and ways of speaking—and each other. Language maintains their humanity:

Conversation, no matter how clumsy it is, no matter how loaded with misunderstanding, maintains time, nurturing them, helping them remain people in some incomprehensible way. Talking, prattling, even arguing: it isn’t a question of entertainment. Words offer them safe chains, something to keep them afloat, causes and effects, although not yesterdays or tomorrows, which have become meaningless expressions, but continuums, continuums all the same: that is what speech gives them.

Although we learn much about the women’s past lives, especially Shlomith’s, the main story takes place in the white space and is about the women coming together and communicating. Imperfect, prejudiced, and self-centred as they are, in order to gain release the women have to share their stories and, what’s more, participate in and think about each other’s stories.

In this liminal space, Oneiron works on language—what happens when it fails and how it enables communication and social existence and so creates communities. Referring to her imagined community of women who have not chosen to be where they are, and yet must “struggle, think and think a bit more,” Lindstedt reiterated her novel’s message in her Finlandia acceptance speech: we “must make use of the possibility of solidarity.” How well, then, does Oneiron take up its own message? Not flawlessly: sometimes it wavers. Oneiron is a haunting fantasy about a threshold space filled with words, which may also be a valuable tool for examining standpoint theory or authorship and its limits and rights. Perhaps most provocatively, though, Witesman’s translation brings to the Anglophone world a demonstration of what Finland understands by the word “international.”