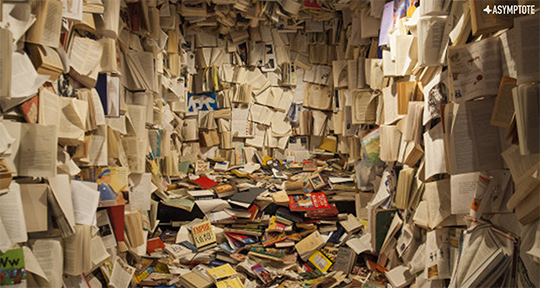

In Kevin Claiborne’s multimedia work, he sources from personal archives, landscape, and anthropological studies to coalesce a vision of Black American history into its contemporary variations, spanning the realms of collective and private histories. “Starting with the gaps in my own family history, and the space between ‘what I know vs. what I should know,’ the missing information between where my ancestors come from and where I am today, I am digging and mining the sediment of histories, passed down, erased, and avoided,” he writes. In “BLACK ENOUGH,” his 2020 exhibition at Thierry Goldberg, he poses a series of questions against the landscapes of Joshua Tree. Some of his questions, such as “Is Black enough?” and “When is Black enough?,” are clipped in the frame, leaving the sentences unfinished, like the Black lives that are prematurely cut short. Extending his reflections on Black identity and memory, Claiborne’s 2023 exhibition, “Family Business,” took a slightly different turn. Drawing from a box of family photographs, he applied green and blue pigments to the images, condensed moments in which his mother, beaming with a radiant smile, once gazes affectionately at his father. The result is a heightened revision of his family archive, a rediscovery of the ties that bind him to his kinsfolk: their shared passions, dreams, and tears. In this following interview, he speaks on materiality, capturing Black lives in Black contexts, and embedded dialogues within his visuality.

Junyi Zhou (JZ): From the beginning of your career, you’ve combined written texts with visual materials. How did this idea come to you initially?

Kevin Claiborne (KC): For as long as I can remember, I’ve had an interest in the power of words—their potential, their malleability, their limitations, and their ability to shape meaning. I’ve always been impressed with people who have mastered their expression of the written word, and who understand how to literally and metaphorically paint with text. My earliest inspirations were graffiti artists, poets, and rappers, all of whom understood the nuances of language, how the weight of words changes with scale, and how to use text as a material.

When I first started using photography and archival images in a conceptual manner, incorporating text seemed like a logical next step. Words change meaning depending on present context, and context can change depending on the words that are present.

JZ: I know that you started out as a photographer. How do you see your multimedia/cross-media approach? Does it impose certain limitations on your objective (if there is one) as an artist, or is it the ultimate means for you to channel your message?

KC: Sometimes my mixed-media or multimedia approach offers the ability to enhance and increase the complexity of my work, and other times, it shifts the focus from the material composition of the work to the ideas embedded within. Every material has a story, a purpose, a history, and a language or logic to its usage. Sometimes, the material becomes the focus, and sometimes certain material combinations allow the viewer to have more entry points into appreciating, understanding, or engaging with the work. It depends on the context. READ MORE…