First, I want to ask you about Offshore Lightning. I am intrigued by Nazuna Saito’s story. She became a published manga author over the age of 40, worked commercially for a while, and then took a long break to care for her husband and mother, only returning much later, in her seventies, to publish the final novella-length stories in the book. First of all, how did you discover this work?

That’s a great question, because that’s a perfect starting point to talk about the differences between literary translation and manga translation. Though there are exceptions, in manga translation, the publishers generally come to you to pitch a project rather than you going to them. The Japanese collection won a prestigious manga prize when it was published essentially as it is, in 2010, but it was never on my radar.

I got the chance to work on the project because of a translator named Anne Ishii. She’s a multi hyphenate, but in the translation space she’s maybe best known for translations of a manga artist named Gengoroh Tagame who is known for being an influential figure in the Japanese gay manga movement. His most recent book in English is called Our Colors. I met Anne through a college professor, a mentor to me at Bard College. Anne had come to Bard to give a talk about translation and we had met a few times. Out of the blue, she connected me to Tom Devlin at Drawn & Quarterly about this project, Offshore Lightning, and she said she wasn’t available to do it, but that I would be a good person for it. I am really grateful to her for that opportunity. She didn’t have to recommend me; we don’t know each other well, and I was very green, but it goes to show that sometimes, in the translation community, it really is about holding the door open. The fact that Anne thought of me goes to show that people are interested in doing the work of making this community more expansive and diverse. It’s something I think about in my own line of work; I’d like to be someone who holds the door open, too. There are a lot of excellent translators who just haven’t had the chance to break in yet.

I love alternative manga, but I had never heard of this author before. I was contacted in 2019, but it wasn’t until March 2020, that infamous month, when I was in Japan on a Fulbright fellowship at Waseda University in Tokyo, that I reached out to Tom, in anticipation of the fact that I would be going back to the US. I spent the summer of 2020 and a little bit of the fall translating the book.

One of the things that really struck me in this book is the shift between the earlier, shorter stories and the later, longer stories, which Saito wrote on her return to manga. In working on this text, did you notice a shift in terms of the drawing, or a tonal shift as the book moved into the later work? Was that something you thought about while you were translating the work? For me, there was more humor but also more raw pain in that last third of that book.

I think the book is compiled chronologically, so the oldest story is first, and then “The House of Solitary Death,” the story that ends the collection, is her latest work. Yes, I picked that up. In the two last stories, Saito goes long form, and I think that changed a lot about her storytelling. It gave her more room to develop these characters.

I don’t want to say they feel more subtle, because she’s a subtle storyteller in general, but they do feel like the work of an artist who is coming to terms with her own mortality. As you know, she was dealing with taking care of her ailing family members. There is a reflectiveness to those last stories that I think just comes with age. I’m going to be thirty this year, and while I couldn’t relate to everything that was going on in those two last stories, they did resonate with me. The work deals with loneliness and frustration from a woman’s perspective in a very real way.

In Japanese alternative manga, as it’s been published here in the US, there’s been a focus on male artists from the gekiga scene. Gekiga influenced her work a lot; she’s confronting a lot of the same themes that her male forebears have confronted in their own work, but her perspective brings a different texture to the work, which I appreciate. I’m hopeful there will be more female alternative manga artists published in English, who will expand the view we have of manga and its capacities.

One thing that drew me to manga as a child was that there were so many women artists. Comics tend to have a male image, a stereotype that women don’t read them, or women don’t really draw them. Of course, that is not true, and it never has been true, and it’s been challenged and continued to change. I think there’s such a great opportunity right now. Take Saito, who has escaped a lot of readers in Japan, as well. She got her start in manga later than your typical manga artist, and before and after her debut, she worked other jobs, like teaching and journalism. That’s interesting because the traditional manga work culture is its own special hell, and the work can be all-consuming. What makes Nazuna Saito’s work compelling to me, in part, is that she had a life outside of manga. She wasn’t a young upstart who debuted at nineteen, and only knows manga. Her life experiences and interests are rich and varied, and you can see that in the book.

That’s so beautifully put. I think Saito comments on that, in a meta-way, in one of those longer final stories, “In Captivity.” There’s an elderly woman who’s ailing, and her daughter is a manga artist who is grappling with the commercial side of it, trying to make a living. I thought that was an interesting side commentary on the culture.

The daughter is a career manga artist, but she’s not really making that much money off it. She’s making enough to sustain her. The interesting dynamic between those two is that the mom is just so bitter, so curmudgeonly, in so many ways, but, as the story goes on, though it’s never sentimental, never melodramatic, you do get a a window into this ailing woman’s world. She didn’t know a lot of the challenges that her daughter knows, and she can’t relate, and she’s never tried to relate. It also shows, in a subtle way, this generation gap, this class gap that these women were never able to bridge.

Yes, it does. And that brings me into another question I had about the subject of “faces” that’s mentioned in the introduction to the book. Eleanor Davis, a comic artist in the US, says, in an interview I recently read, “How are we supposed to communicate the multiplicity of human experiences without drawing a lot of different characters?” When I read the essay about Saito, I immediately thought of this quote, when Saito says (and I’m paraphrasing): I don’t draw main characters. The faces I draw are like the faces of side characters. I loved that concept, and I thought it was intriguing. I was curious about whether the way that an artist you’re translating draws faces or chooses to do characterization influences your development of the voice or voices for the characters.

Translating manga is a lot about reading pictures—quite literally a lot of the time.

“I don’t draw main character faces,” and she even said something like, “I’ll never be a main character,” because of her own face, which I think is so cutting. But it’s very revealing. A recurring theme in the collection is appearances, and beauty. There are a lot of characters featured, women who are plain and unremarkable, but, in some of the earlier stories, Saito draws these beautiful women. I’m thinking of the story called “Ginko,” which is about an older woman with a disintegrating family. She has this granddaughter who is gorgeous, but then she reveals that her granddaughter has had a ton of plastic surgery that actually becomes an asset towards the end of the story, which I thought was funny, an interesting perspective on how appearances build us fortune, build cultural capital.

A lot of the women in the two last stories don’t think much of their own appearances, and it’s implied that other people don’t either. And I like that these characters get to be protagonists. She creates “supporting characters,” whose faces don’t necessarily lead us to think, “Oh, they’re sexy,” or “Oh, that’s a character I want to read for three hundred pages.” But they are the protagonists of their own lives, so giving them space is important.

I recently read a comic version of The Trojan Women, translated by Anne Carson and illustrated by Rosanna Bruno, in which all the Trojan women are drawn as dogs, and one of the other characters is a talking tree. As I was reading it, I realized the comic is the staging of this play—the illustrations create a performance of the text. I know in manga translation, you refer to the text you turn in to the publisher as “a script.” Does this idea of the translation as a “performance” of a text resonate for you, or is there a different metaphor you use in your own translation life?

Yes, we do call them scripts, because, quite literally, the publishers work from the script format, which is easier to edit than working directly with panels and with the lettering involved. As the translator, you’re creating almost an instruction booklet for other people to work with.

Translation, to me, is like you’re inhabiting something. I’m inhabiting these characters, but also, because manga is visual, I translate sound effects, signs, etc. It feels very amorphous. I’m almost gliding over each panel and touching everything like a ghost. I think of myself, not so much as a performer, but more of like a ghost who’s manipulating things.

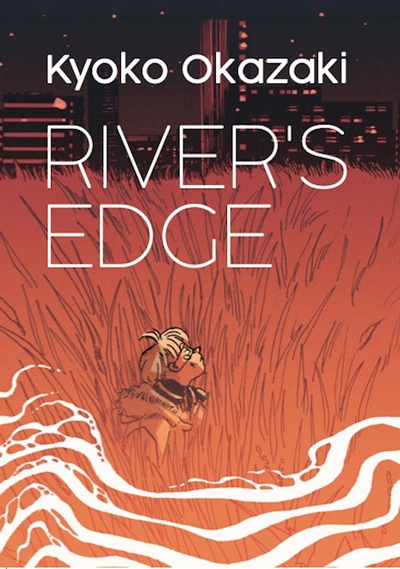

You’ve done a lot of work in translating books for the more commercial manga-sphere, and then these two we’re focusing on—Offshore Lightning and River’s Edge—are being published in perhaps a more “literary” context, or one more akin to what people in the US would call a “graphic novel” or “graphic story collection.” I’m curious about what it’s like as a translator working across this aesthetic span.

With the more commercial works that I’ve done, sometimes it comes down to whether I have the time to do the project, or I’ll read a little bit of it, and it’s interesting, or I see a reader for it, and that’s what drives me. As a reader, I find literary manga a bit more exciting, but the commercial books teach me a lot about voice and slang and “natural” Japanese versus “unnatural” Japanese. I’ve done romance, romantic comedy, interpersonal drama. I just got a copy of this cat manga that I translated. It’s called A Story of Seven Lives. Cat manga is its own incredible niche. I feel so honored that I got to do one, because I think, “Oh, man, I really made it! I’ve done the book for the cat lovers!” Stuff like that brings me joy.

I might have not picked up this cat manga had I not translated it, but now I’m excited that people will have the chance to read it in English, because it’s cute and touching, but also, surprisingly, a little bit dark. I love the surprise factor that often comes with manga translation, too.

With the commercial books that appeal to a wide range, I know that there’s going to be a kid out there, much like me, when I discovered manga as a child, and they’re going to pick it off the shelf, and it could jolt them into this new universe.

River’s Edge, by Kyoko Okazaki, was so complex and full of surprises. I was especially taken with the detail in the drawings, which are so different from the artwork in Offshore Lightning, which has a more open and gestural drawing style (especially in the early stories). I also liked the way, in River’s Edge, two different scenes are sometimes juxtaposed with each other or interspersed: images from one scene and images from another scene that’s happening simultaneously somewhere else. The artist creates dramatic tension through the images, and yet sometimes what the characters are saying is very low key, appearing to belie the drama presented in the images.

With River’s Edge, I read that you had an engagement with this book before you translated it. Could you say a bit about your experience with the book prior to translating it, and about how you worked with voice and tone in that book, given the complexity of the images.

To start, I have had a long engagement with River’s Edge. I first discovered Okazaki when I was in high school, through her graphic novel Helter Skelter, which is this horror-tinged psychological drama, a devastating black satire of the celebrity-industrial complex. I had read that, and it blew my mind. Vertical initially published Helter Skelter and Pink, which are two of her masterworks, in English. I felt so fortunate to later translate River’s Edge because, although I’m not precious or possessive about manga, this is the one title I would have been devastated not to translate or be a part of in some way. It means so much to me, and I was very lucky to work with the team at Vertical to bring this book to a wider audience. I'm especially grateful to the book's editor, Ajani Oloye, who thought of me for this project and was terrific to work with.

Okazaki is so influential in Japan. Her story is also unique and a bit sad. She was prolific in the eighties and nineties. During this time, she was able to reach not just manga readers, but hipsters. She was the rare manga artist able to put out all this amazing work, but also hit the club. She was riding her own wave, so to speak. But then, in 1996, she was hit by a drunk driver, and she’s been on hiatus ever since.

Regarding the information on the pages, and the disconnect between speech and image, the film director Yasujiro Ozu was known for inserting “pillow shots” in his films; he’d pause the action and cut away to a seemingly random object or scene from everyday life. They’re transitional images, yet they create this tonal poetry that’s evocative and emotional. You see this same technique done in manga a lot. It gives a flavor, a texture. There’s a connection to film in the way manga tackles images and paneling—the pioneers of postwar manga, like Osamu Tezuka, were heavily influenced by Disney and live action films, so there’s a cinematic quality to manga’s visual language. The artist’s camera feels very present.

I wasn’t thinking of that cinematic influence. But of course!

I wouldn’t be surprised if River’s Edge was inspired by the American indie film of the same name, starring Keanu Reeves from 1986. Kyoko Okazaki was into film—she’s a big David Lynch fan, for example—and she drew on that love in her work, which is why it’s so filmic. Her chapters feel very much like scenes in a film. When you come to the end of one chapter, it doesn’t necessarily have the same kind of propulsion that you find in some manga, where a chapter ends and you’re like, “What happens next?” She’ll leave the chapter at a moment where it could very well stop right there. But then it continues, very much like a film.

Yes, at the end of some chapters, we feel real closure. And I think her chapters are even called “scenes.” Interesting.

In terms of crafting the voice, Okazaki is effortlessly cool, but at the same time vulnerable. There are a lot of Japanese pop culture references from the nineties in here, so I had to do some research. As I was learning Japanese, she was one of the first manga authors in whose work I could hear the voice in English. Reading her, I thought a lot about the voice.

I love translating the beautiful monologues from the character Haruna, because when you see her on the page, she doesn’t come across as extremely smart, but she has this interior world that is rich and full, and quite deep. I loved when I was able to bring that out in the interior monologue passages.

Okazaki writes a lot of characters who are cool or quirky, or they’re a bit removed, but she’s always interested in the person underneath that. After I finish reading one of her books, I totally believe the characters are still living off the page somewhere.

I felt haunted by River’s Edge when I was reading it, and that’s of course a testament, in part, to the quality of the translation. I’m so glad you brought up those lyrical monologues, which are another layer—in addition to the images and the characters’ dialogue—of the artfulness of this book’s construction.

I love that about manga; it’s not always what is said, but what is not said. I love when a manga goes quiet, and I just have the image to read, because, when you don’t have to have words to say something, sometimes an image can be so potent and powerful.

My favorite spread in the book has no words. I don’t want to give too much away, but there’s a beautiful spread that comes late in the book that changes everything, and it’s the image that sticks with me most, because it is so evocative. It says so much about one character and their arc without having to say anything at all.

Maybe my favorite part about translating manga is when I don’t have to translate it, those silences. Manga artists really understand the power of sometimes shutting up. I think we should all learn a little bit from that.