Derambakhsh worked outside of Iran for many years, publishing in outlets such as The New York Times, Der Spiegel, and Nebelspalter, but eventually he returned to Iran because, in his own words, he “wanted to be in direct contact with the people.” He has been called the Persian Sempé and was made a Chevalier of Arts and Letters by the French government in 2014.

His books include Siyah (Black Miniatures), a fusion of Persian miniature style and black humor, Olampic e Khande (Laughter Olympics), Samphony e Khotoot (A Symphony of Lines), and Agar DaVinci Mara Dide Bood (If Da Vinci Had Met Me).

In early October 2016, I sat down to chat with Kambiz Derambakhsh over herbal tea, coffee, and sweets, in Saless Café and Bookstore in Tehran. The café is the artist’s hangout, a place where he works and meets with friends and fans every day of the week.

How did the Literary Series come to life? What was your initial concern? How do you decide what to work on?

When I was in Europe, I worked for a Swiss journal that gave us themes to work on. One of the themes was the Frankfurt Book Fair. Well, I was in Europe for twenty-two years, and every year I thought about the book fair.

There is also a book fair in Iran, and many journals ask for works specifically on books and literature. Last year, the Tehran Municipality started a billboard campaign to encourage the reading of books. A dozen of my works went up on those billboards.

People do not read enough, and books have a print run of only five hundred to two thousand copies. I have tried to bring attention to books, and to the activities and technologies that distract. Just the other day I drew a cartoon of a boy who put aside his laptop to read a book, and his dad called a doctor, thinking the boy might be sick.

You have also worked on the issue of migration.

Migration, this cry of the hungry people of the world who have been oppressed, is one of the most important issues facing the world today.

My book Le monde est chez moi (The World Is My Home) was published in Paris, by Les éditions Michel Lafon, in 2013. Lafon is a literary publisher, not an arts publisher. This shows the literary appeal of my work.

When I was exhibiting in Paris, viewers reported that, standing in front of my work, they didn’t know whether they were looking at poetry or a drawing or a cartoon.

Why poetry and not, for example, a story? What is it about your work that, in your opinion, evokes poetry?

It is because of the unique softness in the works. They present us with feelings. Cartoons do not usually evoke feelings. Cartoons usually address politics and social conditions.

I once said I sell my dreams, and a paper presented my work under the headline “Factory of Dreams.” An artist is someone who shares his dreams.

In other interviews, you’ve mentioned a desire to forgo language and to connect solely through image. Can you expand more on the relationship between language and image in your works?

My ideal is Charlie Chaplin. He projects his emotions with gestures and behavior. People know him in Cuba, India, and elsewhere. They see him, and they laugh and cry. His language is solely visual, and it works without a word being spoken.

But you do use language in other series.

It is because, for many years, I was primarily an editorial cartoonist, even though I studied fine arts and used to make paintings. Today, my career is a combination of my activities as a fine artist and a journalist.

My ideal, today, is to speak with the least number of lines and simplest of forms, like the Japanese haiku. This is a new age and people do not have time to read long forms, so I work hard to say what I want with visual brevity.

Tell us a bit about the character in your cartoons. Even though your character has global appeal, he does originate from you, an artist from a certain time and place.

Issues addressed, such as environmental concerns or war, have international relevance, but the character is, like me, what the Europeans call a Third World person. There is a sadness to the character of my cartoons, which we ourselves feel, what all people of the East have. For example, when we sing, there is sadness in us, different than the Westerners.

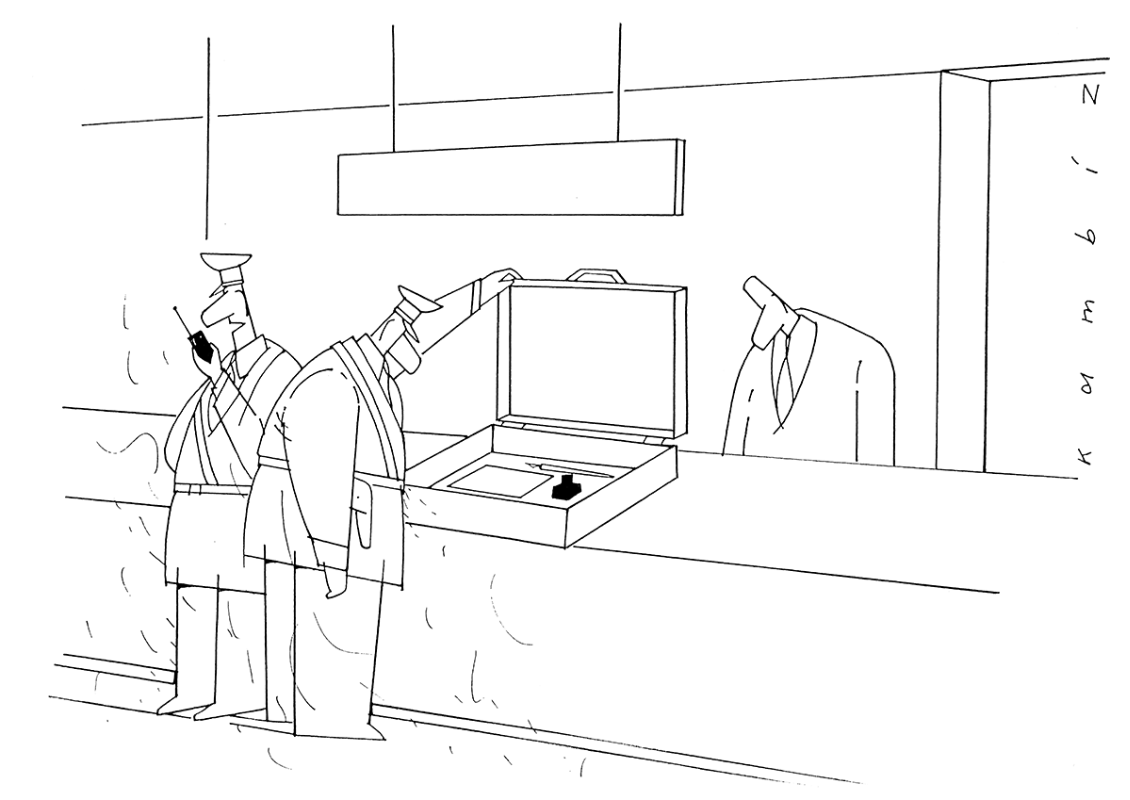

In the beginning, the character was more detailed; I drew the buttons of his clothes or, if his clothes were checkered, I would draw each and every one of the checks. But I reached the point where I realized buttons or checkered patterns were irrelevant. Another interesting aspect of the character is that he doesn’t have eyes, eyebrows, or a mouth. We reveal our fear, for example, through our eyes, or our laughter through our mouth. My character, however, does not have eyes or a mouth, except in rare cases. We understand his emotions through his gestures. For example, when he bows his head, we know he is sad; if he jumps in the air, it means he is happy; if he has his hands under his chin, we know he is thinking.

Among cartoonists outside of Iran, who has inspired you?

I generally love French cartoonists. They taught me that cartoons are not just to make you laugh. The two I particularly like, and who are present in my works, either with respect to ideas or to my characters, are Jean Bosc and Chaval, both of whom committed suicide when they were young. They are the most attractive to me. Also, I admire Roland Topor and Jean-Jacques Sempé. I have learned simplicity from Saul Steinberg. These are all artists who have created a new form of cartoons, one that is not only humorous but also philosophical and beautiful.