beyond my body beyond my skin there’s nothing or maybe the ocean the war my childhood home my mother they are not me they do not merge into me not even momentarily I’m thrown into relief against the dotted lines I have a small body it fits perfectly in the mirror it belongs to me a crumpled bloodied angel will break free from it I am not my mother’s not the angel’s I am mine stop trying to steal me eat me swallow me digest me the pain is me the void the spasms the blood about to flow is me Lucie L. I am the unreachable reflection in the mirror even the blurred blue light of daybreak tinging the room cannot touch me my skin my envelope I live in my body I wait I am in pain I triumph I wait

*

July 29, 1943. In the bedroom of an apartment in the 15th arrondissement, Lucie L. presses her face, her bare breasts, her belly, her white thighs, her knees against the mirror. She looks at her face, contorted, crushed against the glass, her contours, and nothing else. Not the unmade bed, the crumpled bluish sheets, not the swell of the belly that is tearing itself to shreds on the inside and refusing to mold itself to the hard, smooth surface of the mirror. It hurts between her legs, her water broken and infected by the catheter. She steadies her gaze, the bridge of her nose, she feels her body beginning to close in on itself, to tighten beneath her skin.

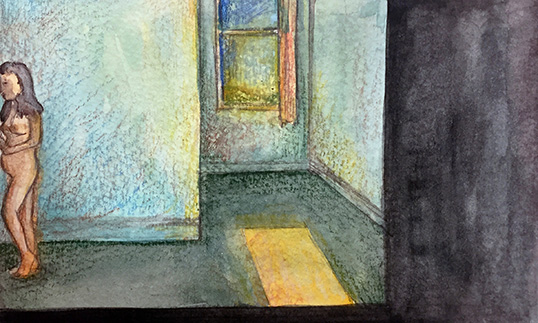

The apartment is empty. She is alone, naked, clinging to the mirror. She waits for the fetus to slip from her, she presses her belly hard against the mirror. She is afraid. In the next room, blue light spills across the table, the dust is already swirling. Blue bleeds over the pages of the Petit Parisien, the paper stiffened by the juices of peeled vegetables and the dryness of July, opened—accidentally or maybe not—to a faded headline: “Angel-Maker Sentenced to Death.” In the room, the white shape of Lucie L.’s body against the mirror, surrounded by blue, as immobile as a Hopper painting, and not a sound. Not a movement. Just the little thing dying inside her uterus, and the sting of tears on her chapped lips. A smear of lemon yellow trembles against the pillow, a first ray of sun.

*

Petite Roquette prison, death row. Marie G. is aware of everything in this hour that is no longer night and not yet day. Everything: the roots growing under the shriveled tree out in the courtyard, the keys clinking on the belts of the nuns, even if the guards slip off their shoes, walk barefoot down the corridors on the morning of the execution, she’ll know, she’s sure she’ll hear the socks brushing on the bare tiles, their breaths thickened by insomnia and rum, the odor of black tobacco, their clothes rustling with each step, and long before that, from the dark of the night, the muffled assembly of the guillotine, the screws turning in the wooden holes, the bolts tightening on the blade, the hiss of the cord across the oiled pulleys, the rollers spinning in the grooves of the twin uprights as the blade is raised to the crossbar, and now she tallies up the silences: no screws, no bolts, no tensioners, no keys, no socks brushing against the cold ground. Only silence seeping out.

All I’ve got left is this withered, flabby body, they took away my clothes, the ones I wore when I was broad like the plains. The cell is too big, four meters by two, and that latrine, well, what do I need with a pisspot anyway, I no longer eat, I no longer drink. It’s too much, I want a narrow room made of boards that closes in around me, nothing more. They should’ve seen how the women kissed my hands, the ones whose fetuses I took, they’d weep, one gave me a phonograph, I bought a house with their money. Good wine for my husband, so he’d give me some peace, and for the soft-handed lover, too. And, of course, cookies, candies, cream cakes for my children, it's war but they still have round pink cheeks, and me, I’ve got hips, breasts. I was tall, immense, I wasn’t pretty, I was beautiful.

Marie G. looks to the sky through the skylight. Mercifully, it’s blue today, so she can watch as the day breaks and the passing hours will be more predictable. On gray mornings, the dying time stretches so long. Marie G. no longer has hands or feet, shackles dig into her ankles and her wrists. She only has eyes for the brightening of the light, a larva whose eyeballs swallow up the whole head, she measures the shades of yellow that mingle with the blue, that intensify, that delay death until tomorrow for the fiftieth time. Translucent, lusterless embryos flitter around her face, she can’t manage to swat them away, but the day dissipates them one by one. At last the cell is empty. Golden. Marie G. finally falls asleep.

*

Henri D. scratches the scar on the back of his hand. It barely bleeds, the skin has hardened, its flesh waxy and deformed. Henri D. mutilates his skin, he needs this pain to chase away the phantoms, to feel life coursing through his hand even as his mother’s ghost sinks her teeth into his neck. He holds a slip of pink paper between his fingers, a police officer on a bicycle brought it yesterday. It announces the execution of Marie G., abortionist, tomorrow at daybreak at Petite Roquette. The other ghosts coil around him, caressing his wrinkles, his white hair, trying to plumb the depths of his pupils. Their eyes hurt the most, they overflow with hatred. It’s daybreak, that’s when the forty kilos of metal sliced into the napes of their necks, and blood and spinal fluid gushed forth; that’s when Henri D.’s body starts to grow outward, monstrously, limitlessly, the body of God. I look into the eyes of the murderers, I search for their victims’ suffering, I cannot look away. I drop the blade, an electric current runs through me, the head is severed and I’m still watching the eyes: they blink, the eyelids flutter and close, dead with the suffering that has lodged itself in them.

Henri D. runs his hand across the lace tablecloth. Underneath it, the waxed wood smells of piss. The tickings of clocks, watches, and alarms overlap. Georgette, his wife, is sleeping soundly. In the doorway, his blue face, his greasy, pearlescent skin. The slip of pink paper dilates his body, hers too, she swells with each execution; everyone knows it’s her, she’s the woman who possesses Henri D., the man with the right to kill.

An abortionist. Henri D. shivers. He’s already drunk a half liter of white wine. The roof of his mouth feels raw. He peels the label off the bottle with the edge of his nail. He rubs his thumb across the rounded surface of the glass, the blue of the breaking day iridescing across it like a puddle of gasoline. An abortionist. Henri D.’s greatest fear is finding nothing in the eyes of the condemned, neither victim nor crime, when it’s one of the resistance fighters, the communists, I force myself to believe they’re filthy pigs and I want to vomit from the terror, the shame, I can’t find a victim in the depths of their gaze, I can’t see anyone’s suffering in their eyes. I search, I can’t find it, I break into a cold sweat, I’m afraid, the blade falls and my whole body contracts, the ghost of my mother crushing my throat, she’s strangling me, she doesn’t want a son like me. I’m the Chief Executor of Capital Punishments, in other words a butcher, I do this for her, I’m paid a lackey’s wages. I kill, my body swells, heavy, mighty, I kill.

Henri D. sucks the blood that beads on the back of his hand. The day creeps through the shutters. Henri D. opens them just enough to be blinded by the sun.

*

Lucie L.’s most distant memory is a face above her cradle, a face that fills her field of vision, and in the middle of the face, a bright red mouth puckering around the syllables of her name: the lips come together as if about to blow a bubble, then stretch across the opal of her teeth, Lu-cie. Lucie L. can never describe the face, it’s too hazy. It only takes a whiff of talc or the pale green of a wall like those of her childhood room and suddenly the face and the pursed mouth reappear. They vanish almost immediately, as fleeting as the residue of a dream. The sound remains, it’s perfectly clear, one syllable after the other twisting maternal lips into a smile: Lu-cie, Lu-cie, the baby in the cradle mimics the smile, they remain like that for a long time, captive to their smiles. Sometimes another woman’s voice—an aunt’s or a visiting grandmother’s—echoes the syllables of the maternal name: Lu-cile. The sounds blend together above the cradle, the sky is filled with rapturous sounds that double the mother’s golden smiles, lu-cile-lu-cie-lu-cile-lu-cie-lu-cile, and although the child will only learn it much later from the mother or from a Latin text, she already knows intuitively that Lucie, lux, is the name of the light. Every morning of her childhood has strengthened this conviction: the two syllables of the wake-up call ring out, Lu-cie! at the exact moment when the light floods the room, when the curtains are flung open, they make the sun rise.

More distinct, years later, the maternal smile warped by the refraction of bottles filled with turquoise, pink, violet, lemon-yellow, raspberry-red syrups. A game of hide-and-seek in the warehouse that’s been deserted by the father who’s traveling, by the bookkeeper, by the workers, an evening or a Sunday afternoon, when nothing—neither voices, nor clattering typewriters, nor ringing phones, nor bodies sweating with exertion—can spoil the sweet spectacle of the glimmering bottles. The warehouse is just a couple minutes’ walk from the house. They go there when the light tumbles down directly onto the roof. Mme L. counts to twenty, then starts looking for her daughter. She takes her time finding her, she makes out her silhouette behind the fizzy bottles and pretends she doesn’t see it. She calls, Lu-cie! from beyond the glass, her lips swelling through the thickness of sugar, her eyes undulating, Lu-cie, Lu-cie! and the child holds back her laughter. To frighten her mother, she clinks the bottles against each other, gently, touching the tips of her fingers to the glass. She weaves her way through the rows, gets lost among the colors, the syllables of her name taking on the tints of the syrups, the taste of marshmallow, of bluebottle, of bitter almond or of rose that she and her mother, perched on the rungs of a stepladder, dip their fingers into after the game. They play again, a little later, the mother’s mouth floating past the liqueurs—violet, green-apple, anise—that color the child’s name. The little girl knows perfectly well that Lucie is the other name of joy. And that her reason for living, clear as the glass around her, is to make her mother happy.

Often, Lucie L. resists the maternal call, come try this one! The aroma of butter and vanilla—what a treat—but still she resists, she savors the power of her disappearance. The mother insists. Her voice takes on a slightly different tone. She trembles, suddenly anxious. Lucie giggles at the intensifying tremors. She hides behind a tree in the park, behind the door of the bakery, she disappears. And the more the voice trembles, the more the gentle tones wear thin, the more Lucie’s stomach hurts, a pain that is also pleasure. Finally, on the verge of tears, she reappears, she hurtles down the staircase, she throws herself into her mother’s arms.

Lucie’s mother is a bird, a river, a rosebush; it’s thanks to Lucie, thanks to the joyful masks she wears to please her. When she cries, her mother hides the remnants of her tears beneath a cloud of powder, but her mouth is pale and her eyes bloodshot—this blotched face is not Lucie’s fault. And because there’s no one else at home except Lucile and Lucie with their captive smiles, the tears must necessarily be the fault of someone who’s not there. Lucie never imagines there could have been a child who was stillborn or never conceived, a real or wished-for lover, some formless, nameless ill tangled in her mother’s flesh, in her mind, she never thinks there could be anything but the truth, the only possible truth given the only known absence: that of the husband, her father. I have a mother and a photo, says Lucie L., a smiling snapshot, a light gray suit and a fedora, roaming the planet, sucking tender mangoes, sugared oranges, sweet mint, fruits with strange names, mangosteen, lychee, kiwi, passion fruit, whose color and consistency she’ll never know, foreign lands that come back as syrup, as sickly-sweet liqueurs in huge cases. Mme L. cries noiselessly, the more she cries, the more she powders her face and her skin becomes snow. Lucie kisses her eyelids, devours the floury tears and the chagrin. Lucie never cries. One Sunday, she’s twelve or thirteen, she goes out to play at the neighbor’s and comes back to an empty home. She calls out for her mother. No response. Neither she nor her mother have played in the warehouse for a long time now, but that’s where she runs, straight to the warehouse filled with syrups, her mother is dying there, she’s sure of it, it’s inexplicable, she’s Lucie, the light, the happiness, her mother’s sunshine, she knows it. She runs to the warehouse, rushes inside. It’s a beautiful day, thousands of gem-colored patches quiver on the walls, the ceiling, the cement floor. Sitting on a crate among the shards of broken bottles, her hair undone, Mme L. holds her bloodied hand.

“Oh, Lucie, it’s you . . . ”

Tears roll down her cheeks, digging furrows in the powder, she doesn’t try to stop them, she just says with a smile, “Well, there you go, I made a mistake.”

Lucie kneels, takes her mother’s hand. She licks her palm, it tastes like iron and grapefruit, she licks until all that’s left is a deep ruby-red gash. Her mother murmurs Lucie, Lucie, Lucie’s head against her chest, and she’s a bird again, a river, a rosebush, it doesn’t hurt anymore.

Lucie isn’t the name of absence. There are so many, so many absent, within each family member’s name, so many dead among the living: four Sabines, four Marthes, and three Hortenses, mothers, daughters, and sisters dead one after the other, like the pretty little red-headed cousin carried off by leukemia, replaced a year later by a homonymous baby, another Hortense L., who died shortly after birth, passing her name on to a third girl, a sickly, sad specter who killed her mother during delivery. There were three Jeans and five Léons, splinters from the broken branches of the family tree. Lucie isn’t the name of a deceased; her name is nowhere repeated in curling black letters on pale yellow paper. Lucie isn’t absence, she’s the unique, the living, she is lux, the light that never fades.

4:50 a.m. Outside, it’s daybreak, mid-summer, the leaves of the trees lining rue de Vaugirard are still supple and warm. Lucie L. naked and blue, pressed against a mirror. Five letters without memory, without obligation, it hurts, I cast out my mother, the red angel, the catheter between my thighs empties me of everything that isn’t me. It is my right to feel pain. So many have died, uteruses rotted by bundles of parsley, infected by enema syringes, punctured by iron rods, it was their right, am I going to die so I can be my own? I don’t have a name anymore, I have two L’s, I am so small. It is so cold.

*

This year, 1903, fifty thousand four hundred and sixty-two Maries are born in France, without taking into account the Marie-Louises, the Marie-Claires, the Marie-Annes, the Marie-Céciles, all the hyphenated names that evade the statistics but will soon end up shortened to a simple Marie. Nine hundred and ninety-one see the light of day in the Manche, including twenty in Fréville alone, and if we consider the whole mass of Maries, from nurslings to old ladies, the bourgeois women with white hands and the fisherwomen, there must be at least several hundred in Fréville, maybe more. There are three Marie G.’s around the same age in town, one of them lives on rue de la Pêcherie. She’s the youngest child in a family that has six others. Little Marie G. doesn’t know anything about these statistics, but she’s living them, the syllables Ma-rie echo through the streets of the town, at school, in church, like so many other familiar and indistinct sounds, the hoofbeats of horses, the creaking of carts, the waves murmuring in the channel, the wind hissing down the coast, shopkeepers and barge haulers shouting, sounds that belonged to no one or maybe to everyone, you had to learn not to turn around or else always to turn, without hesitation. Some Maries know how to keep their ears open, to distinguish, amid the tumult of the port and the day, the familiar voice of an acquaintance, but even the most delicate ears—due to their staggering number—can never be completely sure, and Marie G., the one from rue de la Pêcherie, knows that, in the end, she doesn’t have a name. At home, three Maries died before her, she never knew them. Her mother demanded that she live.

“It’s wearing me out, this sadness, look little one, you have to be strong, I can’t keep going on like this . . . ”

In her mother’s mouth, she’s “the little one,” and the members of the family, following suit, no longer call her any other way. So, Marie G. dedicates herself to becoming the little one. She fades away, she blends into the background, a gnat ready to take flight, monochromatic with the walls that surround her, she moves noiselessly, barely breathes. Marie is the other name of oblivion. Sometimes her mother thinks she’s alone as she bends over the sink, her father, too, his legs up on the table after all day in the fields. Crouching in a corner, Marie G. clenches her calves, the ropes of her muscles, the veins violet under her skin. Her eyes follow the swaying of her mother’s falling-out hem, the straw tangled in its loose threads, the hand reaching down to brush it away. Then they see her at last, the mother or the father, by accident, her little eyes lost in the shadows. They gasp out her name and, startled to her feet, she flees for her life in any direction, far enough to calm the battering of her heart. At school, she’s Marie-la-Pêche, and later just la Pêche, to distinguish her from the other Maries, and especially from the two Marie G.s. But when she dreams, she’s Aurélie and there’s no initial afterward because there’s only one Aurélie and it’s her and she’s wearing one of those long dresses she saw on headless mannequins in the window of the Cherbourg shop whose name, Aurélie, is spelled out in golden letters. She’s not quite sure if it’s really a first name or if it’s a place or just some invented word, but she remembers the dazzle of the letters as she hurried past with her father one market day. The horse was trotting along and she’d had just enough time to glimpse the white and mauve fabrics; she was sure they’d feel soft as a baby’s skin. She read the seven letters in her head one by one, then the word took shape, Aurélie, a lilac poem, a secret she’d keep forever.

At the farm where she was placed when she turned fourteen—a servant like her mother—a Marie had preceded her, ten years her elder. So she was still “little one,” which wasn’t so bad because the first Marie, Marie T., said it prettily, without lingering on the i like everyone else did. She pronounced the two syllables with equal emphasis, as gently as if she were calling in the hens before scattering their grain or luring a kitten over to scratch behind its ears. At the farm like at home, she’s small and invisible, silent, docile, neither well nor badly-treated, she never complains. Marie is the other name of indifference. Four years later, a waitress in a brasserie, she’s called with the snap of a finger or an empty glass held aloft. They’re all men, they don’t know her name, the polite ones call her mademoiselle. And still, they look at her in a way no one’s ever done before, is it just them or is it her chest, her swelling hips, she no longer manages to blend into the color of the walls, to disappear, and she doesn’t mind. By night, Aurélie longs for silk sheets, bunches of roses, a De Dion-Bouton automobile, she wants to dance, she wants to love, to smoke imported cigarettes and wear a hat. Marie G. starts to drink, she gets a little tipsy and imagines she’ll really have it all in the end, and sometimes when she’s drunk and catches sight of herself in the mirror that hangs on the back of her door, she sees Aurélie in a suit and a hat with a half-veil, ready to sail round the world. It doesn’t last. The room is ugly, the bar is ugly, the men are ugly, Aurélie can’t change that. Marie G. starts to steal. Shirts. Alcohol. Money. Life collapses around her like a catastrophe.

Worn out, Marie G. marries a military man. She withdraws from the body that receives him, his organ, his orgasms, his sperm, she only accepts his children, she allows herself to have his babies, even the three that will die just like her three sisters Marie. She draws them pictures of the wind-up dolls with porcelain cheeks, the electric trains, the seesaws, the hula-hoops they’ll never have. None of Marie G.’s lovers will make her bigger, she’ll always be a slight woman with a cringing body; it’s her imaginary lover, Aurélie’s lover, who will play with the letters of her name and trace out the verb A-I-M-E-R, to love, across her skin.

She’ll become an angel-maker by accident at first, then because she knows how to do it, then later because it makes her body swell. She has power and money, the little monochromatic girl dies, Aurélie fades into the distance, becomes a memory. But none of the anonymous women who lay down across the kitchen table, led to her by word of mouth, will know her name, not even her first name. Angel-makers do witches’ work and witches get hunted down, they end up dead—even if she hasn’t realized that yet—and for these mutilated bodies, she’s no one. Marie G. inserts the catheter into their vaginas, she squeezes the enema bulb.

“It’ll fall out on its own. It’ll bleed, then fall out. We’ve never seen each other before, never spoken.”

That’s it. In their secret prayers, the women invoke the abortionist as “the lady from Cherbourg.” They’ve already forgotten her face.

It’s 4:50 a.m. In her cell in Petite Roquette, Marie G. falls asleep. Ever since the tribunal handed down the sentence, her name began to exist, first and last. They call out her name in clear, unwavering voices in the courtroom, during the indictment, during the statements. She’s Marie G. and no one else, and she replies, sure of herself, when those syllables are pronounced.

Tomorrow, at dawn, her head will be cut off. But history won’t preserve her name like those of Charlotte Corday, Gabrielle Bompard, or Bonnie Parker. Millions of bodies are being snuffed out in the war, the execution that will take place tomorrow isn’t even newsworthy. Marie will be the other name of oblivion.

*

I am not Henri D. My last name has something to do with baking, I am not a baker. Henri is not my real first name. It’s the other name of untruth.

I had a double first name; it died with my former life. I was a mechanic, an exceptionally gifted mechanic, I travelled the world, from the Mediterranean to Cochinchina, from Saint Petersburg to the Indies, I repaired car engines in Saigon and motorboats along the Neva. I’m not a baker, I’m no longer a mechanic. I had them put “legatee” on my marriage certificate. My son René knows me as the boss of a bicycle shop—and in my spare time I am. According to public records, I don’t exist: no name, no profession.

I am Jules-Henri, I am an executioner. My mother chose my name. My father described the scene to me: she was holding me in her arms, there was blood in my hair and machine grease under his fingernails. He’d just left the factory, he looked dirty, his skin crusted black, he stank, he couldn’t bear to touch me. My mother declared I was Jules-Henri in a voice that brokered no dissent, as if she’d recognized me, oh! Jules-Henri, so you’re our son? My father called me Julot, my friends too, but never my mother. I was Jules-Henri for five years, from 1877 until 1882, in Bar-la-Duc in the Meuse. After that I was everything else, anything anyone wanted, Julot and fifty other names based on mine, shortened, lengthened, translated into exotic languages or silly nicknames. My mother became a phantom and so did I; shout out Pierre, Émile, Hippolyte, and I’ll answer your call, I always answer, I’m no longer Jules-Henri to anyone.

It was a transparent woman who called me by name. I felt like glass, like her—I mean, fragile—whenever I heard my name in her mouth of glass, felt the chill of her smooth glass hands on my cheeks, those glassy eyes glinting in mine, blue I think, or gray, I’m not sure anymore, but piercing and always wet. I’d trace my finger over the veins of my mother’s temples, they branched out at her cheeks, across her brow, over her throat, she’d say Jules-Henri and I was afraid I’d shatter to pieces between her teeth, I’d shatter her, it hurt to hear. I wanted her to be quiet. My mother was strong, solid, rosy. The way she was before the sickness, that’s the vision I summon when her ghost tries to sink its teeth into me, demanding my blood, I tell her, look, that’s you, I must be three or four, I can’t see your face because I’m in your lap, facing the fire. You’re frying apple skins you’ve dredged in flour. When you snatch them out of the boiling oil all I can see are the tips of your fingers dripping hot oil. You blow on them. You ask if I want sugar, I say yes, and you put the apple skins on a plate, you dust them with sugar, I eat them, burning the roof of my mouth. I remember how you’d never touch me until you’ve washed your hands. You soap them, you dry them, you caress my cheek. I like them better dirty, your hands, when they’re soft and warm. The contagion is completely harmless after it’s been killed by the soap. Your chest feels clear now, just a touch of bronchitis, but you’re being devoured by infection.

There are other visions: I’m running across the room with my brother, we’re knights, we’re galloping astride our horses, clopping our feet against the floor, I’m the major, I give the orders. You’re leaning against the window, you raise your hand to your forehead like a damsel in distress, you say, “You’re making so much noise, children. You’re wearing me out Jules-Henri, you’re killing me.” She’s standing, not yet transparent, the moment is near but there will still be a few more weeks or a few more months, and she says I’m killing her. I don’t realize it, I don’t stop, I play, I yell, I battle my enemies, there aren’t as many fried apple skins, but I don’t think much of it, she doesn’t wash her hands anymore, she doesn’t go out anymore, but I’m still a dragon, a werewolf, I hide in the shadows with my brother, we’re always victorious, we shout to Papa that it’s all over, the enemies have been hacked to pieces. And all the while, my mother warned us, she’s dying. But not right away. First, someone else lays down in her bed, a skinny woman with thousands of bones who coughs up blood. I ask her where my mother is, she answers that she is my mother but I don’t believe her, she says Jules-Henri, my boy, and I recognize her voice. I apologize, I’m run through by her bones, please forgive me for killing you, I didn’t mean to, I thought it was a joke, you’re killing me Jules-Henri, you’d say like a tired princess, now give me kiss and we’ll forget all about it, okay, I promise I won’t yell again, I won’t run in the house anymore, and you won’t wear yourself out, you won’t die, one kiss and it’ll all be over, okay Maman, okay? It’s too late. I killed my mother.

I don’t play anymore. I don’t yell anymore. I don’t laugh. I don’t make a sound. I keep my distance from women, teachers, girls, my stepmother, I flee from them, I look away, I try to avoid speaking to them, I know I could kill them. In Paris, the teacher tries to explain the word “mutism” to my father. He nods his head gravely, he reports the word to my stepmother, they seem simultaneously reassured that there’s a word for me and worried the word is that one; I’m not sure if “mutism” is a disease or a defect and then I realize they’ve seen right through me: the teacher repeats the word, “mutism,” as she draws her finger slowly across her lips, from right to left, from left to right, I notice the pale pink nail at the tip of her finger, it reminds me of André H.’s threats, his finger just a little lower, right under his chin, ready to give me a thrashing if I don’t let him have my cookie. Mutism means murderer. I’m not Jules-Henri anymore, not the boy who eats fried apple skins on his mother’s lap, I’m not even her murderer anymore, I’m a murderer, period, and it’s plain as day. Twenty years later, I killed a second woman, Ayanna, a prostitute from India, she told me she loved me and I believed her. She didn’t charge me enough for the nights she spent with me, she twined her tongue with mine, uncurled my fingers and let the money drop from them, pressed my hand between her legs and murmured sweet words I couldn’t understand. I saw her again one night, a knife at her throat, one eye gouged out, teeth broken, on a dark street where her pimp stole my wallet, where she collapsed to the ground, in the mud, her heart stopped. I had a tattoo of a dagger wrapped with a snake inked on the back of my hand, a symbol of vengeance, it hurt and it was good. Then I wept, because of the needle or because of my cowardice. I can’t stand to see suffering anymore, my wife Georgette is a midwife, her work makes my skin crawl, I can’t bear the sight of the blood on little René’s skin, the doctors, the dying, I flee from them, everything related to nerves and flesh makes me numb with terror. A lot of the time my name is Jules-Henri and I’ve just turned five.

Georgette called me Henri from the very start. I let her. Jules is slang for chamber pot. I’d never thought of it, but she did, right away, the very moment we met. She laughed, said I’ll call you Henri, you don’t mind, do you, because Jules . . . well, Jules, you know? Later, she read in a magazine that Henri comes from Haimeric, which means “king of the manor” in Germanic. I didn’t have anything to say to that, it was understood, I’d be Henri, Henri D. She made Jules disappear just like she erased the tattoo one day, by decree and with no possible appeal, she watched unflinchingly as the burning hot plate of an iron singed off all the skin from the back of my hand. One by one, she scraped off the little pieces of skin that had stuck to the iron. Two weeks later, she peeled off the dagger and the snake, then bandaged the raw flesh under a layer of lard. Now she insists I wear gloves. I scratch at my scar, I flay myself like my mother tears into my throat, I’m only the king of the manor in my wife’s fantasies and when the blade falls.

4:50 a.m. Henri D.’s mother is fed up. She tears at her son’s hair, bristles against his chest, she scratches him where the skin is so soft behind his ears. Henri D. walks into the living room of his furnished apartment on rue de la Convention. He waves his hands in front of his nose as if he’s swatting away a fly. He imagines the face of the abortionist, he sees a red-head with red eyes, then a brunette as pale as snow. His visions fade into the drabness of the décor, the Dufayel furniture that fills rooms all across France in endless iterations, sale-priced all year long, ready for delivery and warrantied for three years—an imitation Louis XIII dining set in antique turned oak embellished with grapes, ornate scrolls, foliage, and arabesques, a side table, a buffet, a drop-leaf dining table, caned chairs, modern hat-tree number 134 with copper accents and marquetry panels, a gothic-style executive desk. He pauses in front of the varnished mahogany and beveled glass of the mirrored armoire. Like the table, it smells of piss, Georgette waxed it yesterday. He sees himself in the full-length mirror, his aureole of sun. He feels like crying. Tomorrow, he will be the Executor of Capital Punishments, but for now, his body is shrouded by blue pajamas that sag at the knee, his cheeks stubbled, his breath thick. He is what the newspapers would call the Average Man.