Rue de l’Odéon (6th)

Life rushes around him, but he’s not involved. The city rumbles comfortably, but he doesn’t belong. Homeless? What a joke. He’s already been here eight years. On the same ventilation grille. Staring at the window of the same café. The passersby grow old and die. He is eternal, stuck under a trapdoor in time. The devotion of those who wanted to help him has worn out. Nobody can imagine any other life for him now. He doesn’t care. He knew it could never happen.

Sometimes he throws insults randomly about. It’s relaxing, this sudden emptiness around him.

He carefully avoids seeing himself. A beard and long hair, just to be on the safe side. Even if he had a face, there’s no chance he will ever see it again.

One day a woman from his former life passed by, with a violent scent and a sharp jolt to his heart. Thirsting for her to look at him, he asked her for money, she fumbled around in her bag, for a little too long. He wanted to say, “You could never find anything, could you, do you want me to hold your things like I used to, your makeup, your cigarettes?” She handed him a couple of coins, her eyes sliding over him without recognising him, kind-hearted and distant. Her gaze was serious and sad, but what could he do? Two creatures drifting in different worlds, with only a sliver of an opening between them.

He felt relieved.

It was official. He was dead.

Place Saint-Pierre (18th)

Autumn has the colour of promises. Some seasons are softer, more lyrical, more majestic—I can’t think of one more dreamy.

This morning, the world seems possible to him. This in-between feeling is spectacular. Yesterday he’d never had a future, barely any tomorrows. Today, something in the golden dryness of the air makes him almost want to put one foot in front of the other.

It’s a victory, for him, to have the appetite to breathe, to feel curious about the curves the leaves follow as they die. Almost. His body gleans timid joys, seconds of euphoria.

He wasn’t always like this—convalescent, lopsided.

He wasn’t always like this—stranded, and doomed to stay that way.

All it took was one winter morning. All it took was a car. All it took was a brief swerve in time for his wife and son . . . It could have been avoided in so many ways. An infinity of chances could have changed that insane scenario and saved them. But human flesh does not win against chrome, happiness does not deter catastrophes from spreading their sinister music—it attracts them. Day after day he weaves and reinvents these alternative chances that could have changed that insane scenario. A stubborn little bicycle of obsession, turning, second after second, sometimes without his being aware of it.

Come on, it’s a splendid autumn day, a smell of crêpes and roast chestnuts drifts over to caress him. In his situation, there’s nothing more treacherous than softness.

He sits down on a bench, just for a second. Something has stopped him in his tracks, but he doesn’t know what to call it. And then it comes back to him: Today the world is possible, almost. The monster must be tamed. He stands up again. It’s time to go pick up his daughter from school. The two of them can surely make something up. They might even pretend that it is called the future.

Rue Jonas (13th)

He could never have imagined that the world was so big. Sometimes he can’t help throwing himself into it. So many years spent shrinking himself to his allotted space. So many years not being alive. He had forgotten how to walk straight ahead, just as his eyes had forgotten the line of the horizon.

You can never leave prison. You drag it along inside you, and it rattles and clangs. And yet the children squeal and the prunus trees wave their purple branches. You can never leave prison. But the sky is enormous and the streets are his.

Rue Eugène-Poubelle (16th)

It’s a corner of Paris that doesn’t look like Paris. Chunks of short skyscrapers under construction dominating the Seine, a miniature Statue of Liberty guarding the Pont de Grenelle. It looks like New York as imagined by the small-minded. Elsewhere the city is made of stone, cautious and serious, here it is metallic, sparkling, futuristic. He sets himself up on the parapet, he’s early. He comes to all his appointments with this extra time, a stretch he has to fill in somehow without allowing any anxiety about the next stage to seep in. A moment of suspension, which today’s equipment no longer requires. Modernity has banished breaks. He’s a photographer. He works for a famous film magazine. His job is to collect humans. He transforms each of his admirations, sooner or later, into a portrait. He understands the patient greed of butterfly trackers. His gift is to embellish, to wreathe faces with colours that reveal them, to discern madness or softness where nobody had seen it. He’s daring: putting a dead fish into a movie star’s hands, seeking out accidental nudity, giving orders. Every time, it all happens very quickly. He loves this acceleration of time, not being allowed any mistakes. Nothing floating or swaying. He’d love his whole life to be like this, each second counting, permanent tension, inspiration always vibrating. He smokes a cigarette, the curls of smoke drift off into the roar of the traffic, playing in the grey sky. He thinks about the first time he saw this actress, he was a kid, or maybe it was during those years when he was escaping from childhood, just on the edge of a new life. What had affected him most were her legs, and her contralto voice, low and sensuous, that seemed to be their natural extension. She had aged, but he hoped to give her a present of a little of his desire from long ago. He had a penitent and protective tenderness for women whose splendour had eroded. She would be beautiful, in the instant when he pressed the shutter release.

Square Saint-Éloi (12th)

All Parisians of sound mind and body hate pigeons, on principle and by vocation.

They are rivals, pretenders to the possession of the same territory.

Rats, pigeons, and Parisians: the rightful occupants of the City of Lights.

The pigeon—it’s a settled case—drew dreadful cards in the avian beauty lottery. Shady colours, zero elegance. The Parisian pigeon, moreover, is crippled, limping, and all in tatters. Shreds of its feet are missing, and it astonishes us when it somehow manages to take flight. Feather by feather it comes undone, subsisting somehow or other, while its cousins the sparrows, in triumphant squadrons, graciously hop about, stealing crumbs from students’ sandwiches on the wing, and landing on the blue whale in the fountain.

And yet, she likes pigeons. She has a soft spot for them. At her age, now that she only moves with heavy, cautious steps, she prefers their clumsiness to any prettiness. Solidarity of the defeated, of those left behind. At least she had been pretty once, red lips and light ankles. And from her bench, handing out the bread she brings for them, she ponders this mystery: why had she never seen any baby pigeons? Only these adults, already miserable. As if deformity were spontaneously generated.

Lost in thought, she muses on the vertigo of a fall not preceded by a rise, and is jealous of these creatures that have no glorious past to mourn. Never having been, maybe that was the secret.

Pont Mirabeau (15th)

Knowing how much a city can change its face in a few seconds.

From the golden greyness of an autumn morning to the most carnivorous downpour.

From almost mildness to a venomous chill.

From the smile of a girl, so young, so young, to a scornful look flung by a passerby.

From hot coffee to hunger that gnaws the stomach like acid.

That is only for those who are the dregs of the street, the invisible people thrown out to fend for themselves.

You can snuggle up, when the city shifts and shivers, go home, seek refuge in a warm café, call the woman you love.

You have no idea how violent they are, those phones of yours.

The hard part isn’t not having one. They can be found, you’re so clumsy, so prone to losing things.

It’s not even getting them to work. Everything is set up to cadge the crumbs from those who own nothing, rechargeable cards, penny by penny, no need for a bank account.

But voices to call.

Those magical creatures who respond to your desires, deign to let you inform them that you have been here or there.

Those voices, it takes a lifetime to earn them, an instant to lose them.

You don’t realise it, but those voices—yes, grumbling, hoarse, often unhappy—are your most precious possession.

It’s raining, but he doesn’t care.

Without anger, he stamps his heel on the phone he found on the bench a few moments ago and threw on the ground, which won’t stop ringing. Silence falls. Drops of water are sticking to his face. He doesn’t even know he’s cold.

WINTER

Rue aux Ours (3rd)

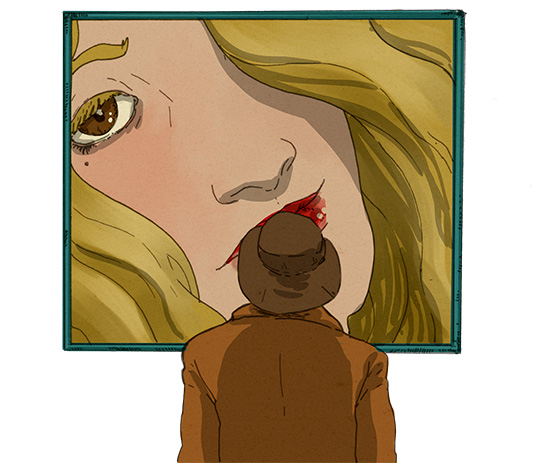

He had always loved silent women. Those who didn’t bother you with their squawking, who cultivated their mysteries.

Every morning he would spend a few delicious minutes with her. Her muteness was not the least of her charms. He knew each of her delights. The uncertain lake of her eyes, whose dreamy colour was between green and blue, like a Greek goddess. The pale bow of her lips.

He loved to lose himself in her face, like in a flaw in time.

Of course, most people would say he expected too little from life, but this woman made him happy.

Every morning, for six minutes, sometimes seven, he could see that perfection existed in this world.

This softened the edges of his day, clouded him with joy.

Then the poster was changed for a lipstick advertisement. An alluring little minx. A low-life imposter.

Since then, his mornings have no soul.

Rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette (9th)

Ever since he left Sicily to come to Paris, he doesn’t know why, but as soon as he gets to a bus stop, he looks around at his companions in their brief spell of waiting and asks himself which one of them will be the first to die. It’s a habit he can’t get rid of, a harmless insanity he daren’t mention to anyone. Crackpot, small-time psychopath, Sunday prophet, he scolds himself. Nothing works: he keeps at it. Today, it’s just the same. There are four of them: a pampered old lady, a guy with a briefcase, a brunette with smoky eyes, and a teenage boy who looks unusually cheerful for his age. If he believed in probabilities, the needle would have pointed to the old lady. If he listened to his sympathies, towards the briefcase—never could stand bureaucrats’ ugly mugs. But it wasn’t a bet, or even a choice. Ever since he had started this strange game, every time, the answers that emerged, immediate and irrefutable, had come as a surprise to him. As inexorable as scientific truth, as frozen as certainty. Today, the answer came to him with a cool shudder he didn’t even try to fight. Of all of them, the first to die would be him.

Place du Châtelet (1st)

Under the banners, desperation is taking hold. There’s only a handful of them, an eclectic clique of coordinators for illegal immigrants. A Bengali cook, a Togolese street-sweeper, a Pakistani rose-seller. No slogans, no shouts, just the weariness of being there. Thick, icy, suffocating exhaustion. Some of them are sitting on the rim of the dried-up fountain. No anger, just sadness. Not even an enemy to fight. They’re waiting.

Rue Frédérick-Lemaître (20th)

This city is not his, everything is here to hammer that into him. The dry hostile language that slaps against his ears out on the streets. The cold, suspect smells, the stingy lights, the jerky violent gait of the women, the looks they refuse him.

But especially this dull threat, the certainty that at any moment anyone can stop him, demand what he doesn’t have, those letters printed on a bit of passport, the safe-conduct that would make him a free man, a man nobody could tell to lay low and sing small. He used to like singing, a long time ago, back in the days when wandering was allowed. Today each step must have a goal, since each step is dangerous. The city is a maze of traps and pitfalls. He is afraid of uniforms, of the armed forces, the forces that preside over fate, that will make him cross the wrong road. The friendly faces of those who try to help him, the echoes of long ago in the voices of his countrymen won’t change anything. This city is not his, as long as it can compel him, with a flick of the hand, a stamp, a charter, to return to a land where he will now be a foreigner as well.

Rue du Dragon (6th)

The ground shakes. Helmet on his head, ears covered, he is nothing more than the vibration at the end of his jackhammer. He is at the heart of a silent pounding. He’s digging. The moves must be precise, accurate. As long as he’s looking at the pavement cracking, the image he’s been chasing away since his morning coffee can’t come and attack him. Since that phone call, since he found out. His father on a hospital bed. His father who will probably. The crackled concrete is expanding. He moves forward. Too easy to have someone call him. The sky looks stormy. The rumble spreads. That doesn’t make up for all those years. He needs to concentrate. Nyet to the grand finale with violins. Sweat is dribbling down his back. His workmate gives him the signal. He kills the motor, takes off his helmet. The gentle hubbub of the street takes over again.

Rue Truffaut (17th)

She’s been pacing back and forth for a long long time now. How long is a long long time, and which way is back and which way is forth, anyway? She asks herself why the administration of the city of Paris has jealously provided accommodation for its staff in some of its ugliest buildings. The town hall of the seventeenth arrondissement, a beige concrete block striped with arrow slits (those things hardly deserved to be called windows). Its replica in the fourteenth arrondissement—the police station of the Avenue du Maine. And that other police station, grey and sinister. Those people didn’t have an easy job to start with, it was scandalous to impose that on them too. It must have been a form of entertainment in the seventies. Some architects are serial criminals, evil recidivists. Soon she is going to climb the steps. But all the same, there’s the post office in the Rue du Louvre, and the old stock exchange building, those are nice places to go to work. She stares at the entrance. It’s only a threshold to cross, a glass door to push. Lay charges. Without thinking, she touches her cheekbone, the incriminating evidence, under her sunglasses. The pain is pulsing under her skin. Lay charges. It’s easy. Identify herself, explain. Why? they will ask. Why only now? Why did she stay? They’ll think, she tells herself, that she isn’t a good victim, that she waited too long. But she doesn’t have the answers, not even for herself. She should have come a sad sad time ago, she had made up her mind so many times, given up so often. Soon, yes surely soon, she will climb those steps and push that door.

Rue Saint-Vincent (18th)

Montmartre is a figment of the imagination. Whoever enters its territory is struck with unreality. The painters (recruited through special competitions by the city of Paris) are water-colouring away, the tourists (shipped here from Japan by the busload) are taking photographs. They all play their roles, and all of them become part of the scenery. Sometimes a Parisian strays in, usually accompanied by a foreign friend or a relative from the provinces. He struts about, sniggering, instead of elegantly accepting his new status as a shade.

In 1910, Roland Dorgelès presented with great pomp Sunset Over the Adriatic, the work of an unknown painter. Success. Sale. Before he revealed the rest of the story, busting with pride. The artist was the donkey Aliboron, property of the Lapin Agile bistro. Delighted to be the naughty boy who debunked the rampant idiocy of the art world, Dorgelès thought he was ridiculing the Impressionists. But our actions sometimes surpass our own intelligence. He didn’t know he had just performed, almost ahead of its time, a gesture of Dada. Created a work of art by the mere decision of exhibiting it. Posterity is unfair, and today he only floats in memory for his novel of the Great War. Turned into a statue, the prankster.

All of Montmartre is an installation, a deliberate construction that cannot really claim to be a fragment of the city. Rather its memory, with commemorative plaques hanging at regular intervals, pointing to the village of long ago. But unreality has great charms, for those who have keen eyes.

Pont Alexandre-III (7th)

It was a murder without an assassin, apparently. The perfect crime.

He had refused to be taken away, couldn’t give a stuff about their bullshit, spending three hours in their van, getting to a night shelter at five in the bloody morning, not being able to sleep in a room with thirty people, his stuff getting pinched, he was so done with all that.

He’d had a drink to warm himself up and curled into his sleeping bag, in his tent, in the shadow of the gilded bridge. And why not? It wouldn’t be the first time. You grow numb after a while. And yet, that night, so similar to many others, something had broken.

It had taken a few hours. And then, gently, the throbbing of his heart slowed down. The world sank, with infinite slowness. The cold reached each atom of his flesh, like a promise. He was weighing anchor, giving up. The first violent bite had given way to this drowsiness. Giving up a game he had never played. His drifting was finally ending right here, not far from the pavement where he had panhandled for so long, with less and less success as his body fell apart, and his voice grew hoarse, and his anger mounted.

Cold enough to crack stone, and he was only a man. As cold as a witch’s heart, and he was only a man. As cold as the grave. As cold as charity.

Passage de la Reine-de-Hongrie (1st)

Understanding the city as a palimpsest. Reading from its open pages. Letters flutter and crash against it, making claims, yelled words of love or political whispers, telling the suffering and the chaos and the panic lurking there. Telling the incredible happiness of a first look, the violence of pitching hearts throwing themselves into forlorn battles.

Street artists’ tags meet the memorial inscriptions to the fallen for France, the hopscotch grids that nail the sky to the ground, the advertising posters. Flyers for Indian restaurants swirl and crumple, sink to the bottom of a gutter to die alongside a useless scratch card, and the city clatters with all these startled words, absurdly pressed against each other. An old advertisement for Cadum soap offers the pedestrians on the boulevards the protection of a pink baby’s face.

On the walls, a few painted letters restore words’ threatened heft and zest: Woman righter. Life is not a fair retail. My nights are more beautiful than your days.

SPRING

Avenue des Gobelins (13th)

She feels joyful, light.

Her parents argued for a long time about whether she could come along. She listened, sitting under the table in the living room, their legs moving around her. Dangerous, said her mother. Too young. Never too early, answered her father.

And here she is, in this rumbling, shouting, singing human stream. At this party, this roaring festival. She doesn’t know what they’re demanding, it was explained to her in serious words, dark words, tie-wearing words, she doesn’t know what they are demanding so passionately but she agrees with them.

The sharp smell of grilled merguez sausages and onions tickles her nostrils. The crowd shouts and surges, she is on her father’s shoulders, all-powerful, invulnerable. As far as the eye can see, the moving colours of marchers. As far as the eye can see, this magnificent anger of which she will always carry a sliver.

Pont des Arts (6th)

It was an unpleasant day, and deserved to be paid back in kind. It had started hostilities with a nasty little drizzle, too sneaky and gutless to be real rain.

When it cleared up, he decided to go out anyway. The sky was grey, without any subtlety, brilliance, or grandeur, its colour spreading even to the skin of the pedestrians strutting mechanically past. A scooter almost knocked him over, leaving a splash of dirty water trailing down his leg. Then in the Métro he was jolted by the carriage’s movement against a woman, who imagined he’d done it on purpose, and voiced her indignation loud and clear. No use even trying to challenge the appalled stares. Crowds love to despise, as long as they don’t have to intervene.

And now, these two cretins posted on the Pont des Arts, in front of the idiotic padlocks that are supposed to make love the synonym of a life sentence. One day the bridge will collapse under the weight of those hideous charms, whose evil glint slashes across the cityscape. These two cretins want their picture taken. He had a pet loathing for this breed, who had forgotten how to live and preferred to hoard the useless images of their wasted moments.

He refuses, they pretend not to understand.

Very well. Bad luck for them. They’ll pay for all the others. He takes the device they hand him. With a precise, perfectly elegant gesture, he flings it into the water. There follows a bit of a hullabaloo, which pleases him.

Rue Ernest-Hemingway (15th)

Paris may be a city where everyone dreams of being a writer, but it doesn’t always look after those writers to whom it offers its streets.

Remy de Goncourt doesn’t do very well at all, with a sinister alleyway lost in the nineteenth arrondissement. A few willing strands of ivy can’t redeem the incoherent sadness of the place, where eras gracelessly pass each other by, among the narrow houses. At least he’s in good company, next to the Rue Edgar-Poe. Curiously, this street is more welcoming, the purple of a lilac bush arguing with a red brick wall, some cobblestones still resisting being sunk under asphalt in the shadow of a fence.

Looking rather grey, Rue Choderlos-de-Laclos runs past the François-Mitterrand Library. Those two might have had a few things to say to each other.

Rue Charles-Dickens, silent and bourgeois, must seem a long way away from the bawdy Paris where Wilkie Collins led him, and whose molls cured his melancholy.

As if it wasn’t bad enough to look like a gloomy garage driveway, Rue Ernest-Hemingway doesn’t even have a single bar. That’s no way to treat your guests.

Quai de l’Horloge (1st)

Passengers make the most of each minute. They know the price of the seconds they share with faces they will never see again.

When the city affords us the illusion that any occasion will be offered again. That figures will come back again to waltz before our eyes.

Each encounter, throw yourself in.

You’d need to be royal and a fool. You’d need to be naked. You’d need to throw away your soul, unconcerned. In a heartbeat, and without conditions.

But who, nowadays, would want such a cumbersome present? How can you not choose warmth and peace instead of something that flutters, trembles and, loses itself?

Avenue Victor-Hugo (17th)

Smoke has the taste of sadness. She only lights up in the grey hours. She goes up on the roof of her building, there’s a skylight that’s easy to climb through. She surveys the city beneath her feet, flashing its bling and its dance hall lights. The dark canyons of its streets, the white mass of the Arc de Triomphe, that gloomy thing she never liked.

Long ago the roofs were her kingdom, she climbed walls, churches. There was a little gang of them, cloak-and-dagger meetings, a community of the shadows. Paris was their mountain, forbidden, clandestine. Plunderers with no booty except thrills at the top of the world, the euphoria of high risk. Vertigo as a way of life. They were unreasonable on principle, oblivious, fiercely.

She remembers that happy stupor, those moments of suspension, sitting on the towers of Saint Sulpice in the moonlight, sucking up the night in great gasps. She can’t believe she used to be so brainless, so mad.

Nowadays she is someone else. The kind of woman who tucks a child into bed at night and that everyone can count on. An indoor woman, domestic, domesticated. Quirkiness kept at bay. She prefers this woman, living with her is easier than when she dragged around that thirst to go to the ends of herself and never come back. And yet, sometimes, when she is numbed by warmth, mired down in it, she escapes. She climbs onto the roof, and lights up a Gitane in memory of that intrepid girl reported missing inside her.

Boulevard Raspail (6th)

One night in 1966, Jack Kerouac insists that his taxi should stop on Boulevard Raspail. He wants to say hello to Honoré de Balzac. The Père-Lachaise cemetery is too far away, and not very tempting at three in the morning. Rodin’s statue will have to do. In Paris, Kerouac experiences satori, an inner revelation, as overwhelming as it is difficult to convey in words. Does Honoré have something to do with it?

Whenever I pass the heavy bronze silhouette, powerful and musing, draped in its rough severity, I now send it friendly thoughts. An illumination would do me no harm either.

Rue de Bellechasse (7th)

Street rounds. That’s what they were called.

Every Thursday evening, she and a few others would get into the charity’s broken-down Kangoo van, and stop by people sleeping rough, to hand out—well, not much. Coffee, soup, smiles, tins of food. A little of themselves.

She kept telling herself it wasn’t about saving anyone. No, just offering them the start of a choice, the first rescue plank if they chose to extract themselves from their hell. Just tearing away a few moments from the barbarous order of things, and weaving in some human softness.

But.

Sometimes she was angry. Taken with a sudden urge (a scandalous, yes, of course, a stupid urge, she admitted it) to shake them.

The infinite capacity of human beings to tolerate anything. Their exasperating compulsion to shrink into the space available.

To take it, again, always, and then just another little swig.

An unstoppable beast, the human soul.

Crush it, drown it, there’s always something left of it.

This evening she was angry because a man she had seen every week for four years told her that he couldn’t imagine sleeping in a bedroom ever again.

Of course she shouldn’t be. It was too easy, the story of choices, what freedom there was once the fall had started, she knew all about it. She was mostly angry at herself, angry in the face of this hope she couldn’t fight, hope like leprosy eating away at her defences. And what was she doing there, as if she could do anything about it, idiot that she was.

That suicidal habit of seeing light in every being, and not even the excuse of faith.

So there it was, she allowed herself this rage that she wouldn’t talk about, this turmoil inside herself, the guilt of witnessing these drownings which she prolonged with soup.

SUMMER

Rue de la Lune (2nd)

One day she disappeared, just to see if anyone would go looking for her.

No one.

Rue Mouffetard (5th)

It was Sunday, since he was there. Each time, going out into the street was more like an adventure. Perilous, uncertain. She stooped beside him, so frail, her arm pressing on his. He felt her falter at each step, with that absolute vulnerability he just couldn’t get used to. She would always say he had grown, even though he repeated that it wasn’t possible anymore, now that he was twenty-two. She looked at him, amazed each time at this handsome young man with his prodigious, infinite growth. She looked at him, and saw the fragile newborn baby against her skin, the mischievous and brave little boy, the teenager who came over to talk about his sad love life only to her, the young man whose unreasonable dreams she protected. Love embraces all of time in a single glance. She had been closer to this gentle dreamer than to her own children, busy as she was trying to raise them as best she could.

Each step was a trial, a small victory at the end of an infinitely slow battle. The cobblestones were treacherous, and the incline of the street too steep, and yet this was important for her. He was all the life she had left at her age, which often seemed grotesquely advanced to her, and what had she even done with all those years anyway? She told him about her street, the one that no longer existed, with its people and its banter, the slightly disreputable Rue Mouffetard she missed, as distant and inaccessible as her own youth. It hardly existed anymore, and always got its timing wrong. Long-gone hours seemed closer than a conversation heard the day before, a fog seemed to shroud even the simplest ideas, words failed her. Luckily Sunday would come along, with the certainty that few loves were as true as theirs.

Place de la Bastille (12th)

The perversity of objects is difficult to gauge. The unfortunate collision, as he got out of bed, between his left foot and his glasses was no fluke. In fact it was undoubtedly the result of a deliberate plan concocted by the suicidal and Machiavellian pair. But, at thirty-four years of age, he was profoundly, desperately, and painfully myopic. Going out into the street, with the hope his optician would take pity on him, was to plunge himself into a fog—one not without its charms, of course, Paris seemed on the point of dissolving, of becoming London or Venice, those cities with powerful disappearing skills—but a fog filled with stumbling blocks, obstacles, and other traps.

The circus of cars roared around him. He was concentrating on the angel of the Bastille when the noise of a car horn and the screech of brakes coincided with the sensation of a hand on his shoulder, trying to restrain him, to call him, to bring him back to the good side of life. A moment of happy confusion.

Don’t get run over, said the silhouette (graceful), who owned the hand (delicate).

I’ve broken my glasses and I can’t see a thing, he confessed.

She laughed, an explosion of fine bubbles of joy, filling him with warmth.

Well then you can always say that a very pretty woman saved your life. (She was the first one to be surprised by this remark, which was most unlike her: the double anomaly of talking to a stranger and to a temporarily blind person. Or maybe it was just one of those outbursts from a shy person, who won’t often bid, but will stake everything on a single card.)

A very pretty woman who looks like a pointillist painting, he ventured.

They smile at each other through the fog, and enter a café where we shall not follow them.

Cimetière du Montparnasse (14th)

What he would lose first was her smell. Then he would be abandoned by the exact shade of green of her eyes, then by the texture of her skin.

She was already crowned with a halo of dubious perfection, a diaphanous veil he knew he would loathe. He suspected that no one would ever talk about her again without lowering their voice.

Widower, what a ridiculous word, at his age.

Boulevard de Ménilmontant (20th)

In front of his caravan, at the gates of the Père-Lachaise cemetery, the last wizard of Paris is taking a breath of air before his next customer. He waters his planter boxes, which luxuriously welcome the punters, and of which he takes particular care. In a little while he will predict a woman’s love life, which he will read in her cards. His parents were fairground people, but he gets his gift from his grandmother. He swings a pendulum, but refuses to enter into conversations with the spirits of the dead. The future is his realm. Only his own and his loved ones’ future remains opaque, illegible, muddled. The gods are frivolous.

The Paris of magical encounters is not dead. Angels and fairies still roam. The sphinxes by the Seine are their accomplices. Faith has not deserted him, at least not modest little faiths. But you need to keep your eyes open, to see the irrational finding its way through the city of the Enlightenment. The fortune-teller who grabs the hands of passersby in the Latin Quarter. The marabouts of the Goutte d’Or neighbourhood. The bingo players in the bistros. And the strangers who agree to meet on the vague promise of a photograph and a few words exchanged online.

Hope without madness is not hope. The most ardent optimism and bottomless despair are close relatives, sides of the same coin. Magic is a fragile thing. That’s why it’s important for those who have the privilege and responsibility of believing in magic to treat it as gently as a sick child, or a bird fallen from its nest.

I’ve chosen my side. I believe in a world where unicorns are not narwhals, where it’s the manatees that don’t exist. I’m waiting for the green flash.

I should have grown out of this I suppose. Never mind. Bad timing is one of my old habits.

Rue de l’Hirondelle (6th)

In the blazing twilight, you would swear that the bronze goddess above the Saint-Michel fountain was perched on a branch of one of the plane trees on the boulevard.

He leads her under the arcades, into the alleyway, nobody to scandalise at this hour, nobody to disturb their pilfered pleasure. Just a lamppost to light the scene, under a full red moon. They coil around each other, kiss, sway. In the shadow of an entranceway, she can feel the wood of an old door through the thin fabric of her dress. The man’s hand slides along her leg. A month since she met him and burst into flames. She hardly knew, before, that a man’s skin could burn so savagely. She feels his hand venturing higher, taking possession of her, so softly, so slowly. With him, each stroke is overwhelming. Incandescence is taking hold. She puts her teeth against his neck, tastes the hollow of his shoulder, breathes his beauty. All of his body is like a miracle to her, his feverish body, his slim, dizzying body. She’s shaking. Love. The word flutters between them, she couldn’t care less, names, worthless, only adjectives matter sometimes. The contours of her body are dissolving. Whatever she has sheltered inside her for a month, never mind its name, is wild, tender, violent, and so carefree. Waves of joy flutter along her skin. She has never felt so friendly towards her own body, this body he desires, to her great astonishment. She is nothing, anymore, but a point, avid, blind, in the hollow of herself. And yet so light since she met him, since he walked into a room one day, looked at her, and there was nothing she wouldn’t do for him, from that first second on. She arches herself against him. The hours spent without him are grey, lethargic, only just enlivened by obsession, the more she touches him the less satiated she feels. She is nothing but expectancy, always the instant where pleasure might not come, at the extreme edge of ecstasy, terror. She wishes their skins were no longer so foreign to each other, could merge, she wishes she could shipwreck into him. Suddenly it happens, she keels over. The night spins, explodes, submerges her. He smiles at her. There’s nobody, at that hour, in the streets, nobody but them, and there’s hardly two of them. An hour that doesn’t exist, stolen from a sleeping city.