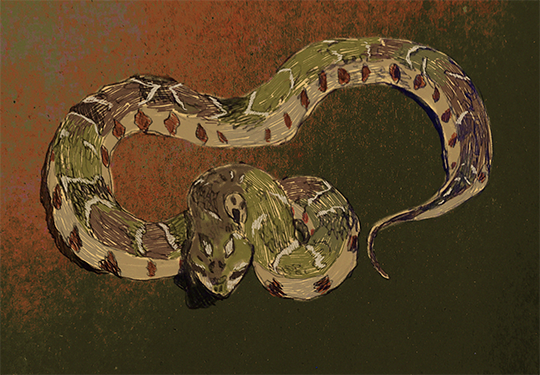

Page 284, rough coffee snake, Nothopsis rugosus, rear-fanged, mildly venomous, harmless to humans. Returning to the article, she placed a neatly cropped sticky note over the offending sentence and wrote the following words in fine red ink: “This translation is rugose, well keeled and granular.”

Then she closed the book and poured herself yet another cup of tea before removing its jacket to reveal the dark brown lithocase beneath. In the middle was a conveniently light-skinned Vipera berus, along the length of which she wrote the words “A New Vocabulary of Translation”, this time in unrepentant black marker.

From now on, the snakes would be her lexicon.

“A subdued, pastel-coloured translation, it blends well with the original” (Patagonian lancehead, Bothrops ammodytoides).

“At times leucistic, this much-revised translation from the Japanese is muscular yet slender” (Aodaisho, Elaphe climacophora).

“Broad, flat, gives a ‘bulldozer’ appearance to the once soft-bodied syntax” (Grandidier’s Malagasy blind snake, Xenotyphlops grandidier).

“Stout-bodied, though with occasional black spots” (Mount Kinabalu pit viper, Garthius chaseni).

“Extremely compressed, it is a rounded, forward-facing translation, which forcibly withdraws the text from its shell” (Keeled slug-snake, Pareas carinatus).

“In English, the author’s writing becomes polymorphic; it exists in more than one colour pattern” (Richardson’s mangrove snake, Myron richardsonii).

“A highly variable translation. Paler anteriorly, darker posteriorly” (Günther’s green treesnake, Dipsadoboa unicolor).

“While the author’s idiolect is overlain by a fine dark strip, the translator’s, I’m afraid to say, is pale” (Malayan spine-jawed snake, Xenophidion schaeferi).

“A highly glossy translation” (Common purple-glossed snake, Amblyodipsas polyepsis).

“Whiplike” (Rainbow forest-racer, Dendrophidion clarkii).

“Very attractive at times, at others the English prose is a uniform grey-brown. Ultimately a defensive display” (African coralsnake, Aspidelaps lubricus).

“Fairly robust, terrestrial” (Variable reedsnake, Calamaria lumbricoidea).

“Her translations glide, but how they do this is not well understood. Her slender and lightweight clauses catch the air as they leap into space” (Paradise flying snake, Chrysopelea paradisi).

“Feels velvety to the touch” (Snouted night adder, Causus defilippii).

“Small neonate sentences are swallowed whole, while larger ones are slit open, allowing the reader to feed on their contents” (Scarletsnake, Cemophora coccinea).

“As with all of x’s translations, it is irascible, chewing vigorously to bring the poet’s lyricism into play” (Barón’s bush racer, Philodryas baroni).

“The English text exhibits an instantly recognisable pattern, though it is more elongate than the original” (Reticulated python, Malayopython reticulatus).

“The Russian prose reacts violently to being handled, convulsively jerking its body about and hissing through this powerful, agile translation” (Rufous beaked snake, Rhamphiophis rostratus).

“A cloudy, mossy rendering, which brings to mind JRR Tolkien’s fictional forest of Mirkwood, Eryn Lasgalen” (Mirkwood forest slug-snake, Asthenodipsas lasgalenensis).

“The translator deftly employs the technique of caudal pseudoautotomy” (Guatemalan spatula-toothed snake, Scaphiodontophis annulatus).

“This translation is powerful and will bite, drawing blood, if mishandled” (Mississippi green watersnake, Nerodia cyclopion).

“Tongue-flicking the source text for freshness, the translation engulfs each phrase in its articulable jaws, regurgitating its compressed remains” (East African egg-eater, Dasypeltis medici).

“Variably patterned, from unicolour to a typical zigzag; this is how we might describe the dying art of translation. Threats include overgrazing by sheep, and habitat degradation by pigs” (Orsini’s meadow viper, Vipera ursinii).

“There are no records of the translator’s reproductive strategy. They are rarely encountered and in dire need of study” (Burrowing cobra, Naja multifasciata).

Her insights seldom went unnoticed, and her notoriety as a critic—the occasional eccentricity notwithstanding—reached new heights. However, as her star rose, she in turn grew ever more reclusive. At time of writing her whereabouts remain unclear, the only remnants of her practice a small brown notebook and the smooth, dry, cerulean snakeskin that lay beside it on the kitchen top.