I start with a cup of coffee at the museum’s bistro. The library doesn’t open until eleven o’clock, so after finishing my coffee I usually have a solid half an hour to walk around the museum. I have two favourite exhibits.

The first is the skeleton of a whale that was stranded on the shore sometime in the past. Enormous, over ninety years old. It hangs from the ceiling.

The whale was nearly fifteen metres long and weighed close to forty tonnes. ‘The royal whale.’ ‘The terrible whale.’ ‘The whale of Langness.’ A sei whale (order Cetacea, family Balaenopteridae), it got stuck in the shallows right near the shore, between rocks that are never covered by the sea, even at high tide. And it died, causing a huge commotion.

It was Friday, 8 May 1925. Some boys from King William’s College found the creature during a break between lessons. Frightened, they jostled the body with a stick, timidly kicked it a few times, and then ran to fetch their teacher. The rest of the lessons were cancelled that day. The headmaster thought the pupils were too excited and wouldn’t be able to concentrate.

The coast guard soon arrived at the scene, and all of Castletown quickly followed.

‘What a fish!’, remarked someone in the crowd.

‘An otherworldly creature!’, said someone else in amazement.

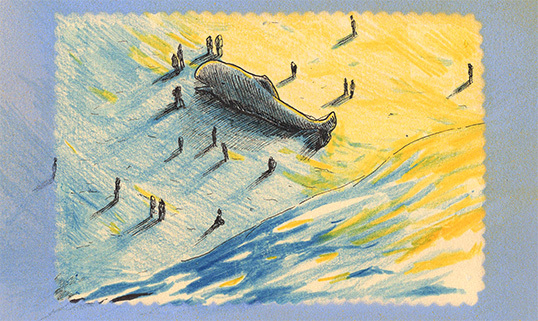

On Saturday and Sunday, nobody on the island talked about anything else; everyone wanted to see the whale. People travelled from Douglas and Peel, and even all the way from Ramsey. Thousands of gawkers. They had to touch it and smell it. Someone tried to lift a heavy, drooping eyelid, someone else a limp flipper. If only they could peek into its mouth, under its tongue, or break off a little piece of whalebone as a souvenir. Just something to keep. Cameras flashed.

The local police force decided to become involved in protecting the whale and hung posters informing people of penalties for damaging the whale’s corpse. The director of the Manx Museum inspected the whale carefully and decided that its skeleton would be suspended in one of the museum’s exhibition rooms. But first they’d have to figure out how to transport the body and then remove the flesh from the bones. How could it be hauled away in one piece?

A few days passed. The onlookers began to leave Langness. Partly because the area was smelling worse by the day. Not even the sea breeze helped. People living nearby began to complain about the stench from the carcass, which was gradually becoming unbearable.

One morning, two traction engines drove up, pulling three trailers connected with drawbars. Museum staff and coast guards struggled with the dead whale for half a day. Once they had finally managed to lift the animal and place it on its unusual bier, they wound thick ropes around it so that it wouldn’t slide, fall off, or cause any other trouble. The newspapers published that day provided detailed information about the route the convoy would take. They advised people to shut all their windows and doors, and to stay away from the road. They could watch the caravan from behind curtains, without exposing themselves to the strong, unpleasant odour.

The distance between Langness and Kirk Braddan, near Douglas, is a good twenty kilometres. The traction engines moved very slowly and cautiously. After a few hours, the caravan reached the burial site. With a loud thud, the whale tumbled from the trailers into a pit that had been dug earlier. Clouds of sand blocked the view for a moment. About a dozen men had been hired to bury the animal—they flattened the earth over the corpse thoroughly. A few years later, experts from London would dig up and clean 162 bones, then reconnect them with rivets and metal rods in the museum. The enormous skeleton, weighing three and a half tonnes, would be suspended from the ceiling.

I’ve gazed at it many times with a mixture of fear and sadness, my head tilted back, before wandering into another wing of the museum where fauna gives way to mankind.

Arthur Caley measured nearly two metres and thirty centimetres and weighed over 130 kilograms. He was the Manx Giant.

In a room on the underground level of the museum, there’s a small display case with his shoes. Black leather shoes—enormous boots, rather, reaching right up to the ankle, rounded at the toe, with a slight arch. Ashen with age and very fragile, they’re at least 160 years old. In the display case, there’s also a metal cast of Arthur’s right hand. It was a gift from America—from the widow of a renowned collector of curiosities.

Caley died in Middlebush, New Jersey, in February 1889. He was buried in an unmarked grave for fear that grave robbers would be tempted by the giant’s bones, which could certainly be sold for a good price. Many a museum would be happy to add a humerus or a tibia from the world-famous giant to their collections. The most valuable would be the skull, of course, but any of the 206 bones would serve its purpose—if placed alongside a normal-sized person’s bone.

Arthur Caley was born on 16 November 1824, the twelfth of thirteen children, in a small house belonging to Anne and Arthur Caley in Sulby, in the north of the Isle of Man. His parents and siblings were of completely average size. At first, Arthur Jr. seemed to be like them. He was no taller, wider, or heavier than his peers. However, when he turned seventeen, he shot up in height and unexpectedly overtook his oldest brother; by the age of twenty, he was the tallest person in the village; a year later, he had left behind the entire north of the island, and soon afterwards he was the tallest person on the Isle of Man. He only stopped growing at the age of twenty-six.

By that time, he had already become famous throughout Europe. He had left the Isle of Man long before and was making appearances in Liverpool, Manchester, and London. All the major newspapers wrote about him, circulating legends about his superhuman strength—how he had lifted a cart full of turnips with one hand to repair a broken wheel with the other; how, for a bet, he had dragged a half-tonne anchor for a kilometre and a half, and so on and so forth. He was said to be the tallest person in the world, and also the most perfectly proportioned—his hands, feet and head weren’t deformed in any way. Caley wasn’t a freak—just a giant.

To see him with your own eyes, to feel frightened by him and then begin to feel at ease with him, you had to pay one shilling. The British and the French were the most eager to pay. In Paris, the Manx Giant appeared in cafés and during concerts, as well as at special exhibitions where, for a greater effect, he was presented in the company of dwarves. He was a true sensation, until 1 January 1853, when it was announced that . . . he was dead. Apparently, he had succumbed to a sudden illness. Today we know this wasn’t true, and that Caley, in perfect health, had secretly left France and sailed to the USA. His closest collaborators went with him, hauling suitcases full of money swindled from the insurance company. The equivalent of £200,000 guaranteed the giant several peaceful years on the other side of the globe, and when the money ran out, Caley was reborn—as Colonel Routh Goshen.

Colonel Goshen once again appeared in the company of dwarves (including the world-famous Charles Stratton, known professionally as General Tom Thumb) and with albinos from Madagascar. Caley wore military uniforms and helmets with plumes that made him look even taller. He was right at home in a circus whose other stars included Fat Eliza, weighing over 220 kilograms, a Russian boy with the face of a dog, and Zip, the missing link—half man, half monkey.

Photos of the huge Manx appeared in the leading newspapers, legends were told about him (which he willingly fuelled), biographies of him were written full of made-up adventures in which sometimes he was called an Arabian giant, sometimes a Turkish giant, and elsewhere a giant from Palestine who had fought bravely on the fronts of nearly all the wars happening at the time. He also had a wife who, several years after the wedding, ran away with her lover, robbing Caley of part of his fortune. According to unconfirmed reports, Caley married twice more and also raised two adopted children. Near the end of his life, he set up a circus tent on his farm in which he displayed souvenirs of his former days of glory—unfortunately, they were all destroyed in a fire. Caley died soon after—at the age of sixty-five, unusually old for a giant. Most people afflicted by gigantism don’t live past the age of forty, typically because of complications resulting from cardiovascular disease and bone diseases.

The Manx Giant was buried in a specially ordered coffin. It was over two-and-a-half metres long and nearly a metre wide. Eight brawny farmers carried it and their foreheads, despite the winter cold, were covered with sweat.