As Lithuanians, we hadn’t felt anything like it since the euphoric 1980s, when every public square in the country had been transformed into a sea of tri-colored flags, the yellow, green, and red of a once independent nation; when tidal waves of patriotism and love of homeland swept over us all. After 50 years of Soviet domination, liberation would prove to be less than a decade away.

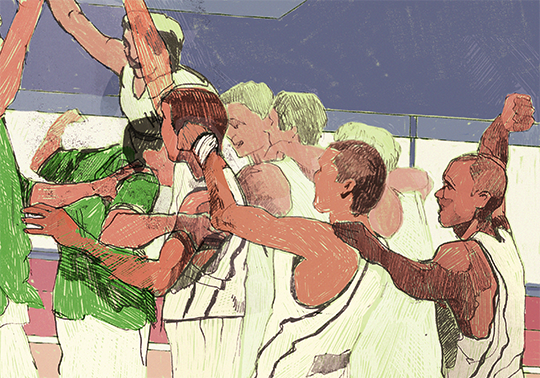

The EuroBasket of 2003 drew entire nations together in friendship. While they may not have cheered us on in Stockholm, they did in Yerevan! Even our faith in God seemed to intensify; church attendance soared. Brother Astijus was asked by a member of the Žalgiris fan club if he thought that God Himself had intervened on our behalf. Without missing a beat, he reeled off that famous line from Scripture: “The Lord God topples the mighty from their thrones and exalts the lowly.” I get shivers up my spine just thinking about it. I swear, it wasn’t just luck. We had tamed the Heavens and brought the Almighty to our side of the court. I remember an acquaintance of mine, who never seemed particularly religious, admitting that he had prayed in front of the TV set and promised a tenner on the church collection plate if we won. When he learned that his prayer had actually been answered, he looked to me like a man reborn. Or the woman who called the rectory in a fretful state, wanting to know if she’d done a sinful thing involving God in our passions for “the hoop.” And she wasn’t the only one. I’m sure the liturgical feast at the holy shrine in Šiluva, which is always attended by great throngs of the Faithful, couldn’t help but expedite all those pleas to Heaven for victory on the court. At one point, during the semifinals against France, I, too, began to suspect some sort of divine intervention at play. The French team was scoring points like crazy. We were falling behind. I started panicking. If this continues, I won’t make it to Sunday. I had just begun to consider some serious bartering with God myself when, luckily, things settled down. Someone must have pressed the buzzer ahead of me. Another pact made with God! Another contribution promised! A Mass pledged!

I particularly remember the celebrations outside my window at midnight. Joyous but deafening. A chorus of revelers. Bells pealing in the town square. Everything beckoned me to come outside and join the fun. But the hoopla came and went without me. I couldn’t risk jeopardizing my obligations; the church administration had not, after all, promised us a day off in the event of victory. Though I might as well have been outside. I awoke the following morning to yesterday’s chants as though to morning prayers: “We will win, we’ll whup ’em good!” The needle on the record had gotten hopelessly stuck, and I slipped off to celebrate Mass with a fight song ringing in my ears. Eventually, in the course of the service, the refrain wore off. The repeated mention of Our Lady of Sorrows—and the image of daggers piercing her heart—brought more serious verses to mind. Besides, the Church is far less militant these days and not inclined to “whup” anybody—metaphorically or otherwise.

That morning Cathedral Square was again filled with activity, and I was gratified to see that priests weren’t the only ones working the early morning shift. A line of street sweepers was cleaning up—conscientiously, religiously—sweeping up the broken bottles and general debris that had been strewn across the heart of the city by throngs of rowdies, who had come hurtling through the previous night. City workers were attending to the telephone booths that, along with the occasional car, had been tipped over in the heat of jubilation. Such is the aftermath of a lot of celebrations around here, even liturgical ones, when the sanctuary is left mired in trash. Otherwise, there was little reason to complain. No store windows had been smashed, the sound of ambulances had not filled the night air, and only minor fainting spells had been reported in Kaunas. Some fans who had caught a glimpse of Europe’s champions in the flesh had, apparently, fallen into a swoon.

So I sit here and I think: could that euphoria be the spirit manifesting itself? And not—as I have heard it said—just another version of the grimaces, the crassness, the lack of restraint we see on “talk shows”? I suppose a case can be made for the latter. I can even see why some would call the behavior of the fans a case of “mass psychosis.” Or “basketball mania.” Or “vanity of vanities,” an expression—thanks to Kohelet—that would be equally fitting. Even some of Father Stanislav’s doleful rebukes could apply—especially his truisms on the impermanence of the material world.

I admit that watching our beer-guzzling, gum-chewing, chip-munching basketball nation posturing in front of the TV cameras and listening to them chant ad nauseam—“we will win, we’ll whup ’em good”—did leave me, at times, weak in the knees and disheartened. At the height of the hysteria, I accidentally came across the dire warnings of St. John “Golden-Throat” Chrysostom, the famed teacher and preacher during the early days of the Church. He warned mankind that life is theater, that the final curtain will inevitably come down on the performance, that the masks we wear will drop from our faces and the roles we play will be rescinded. Our good works alone, rather than the life we acted out, will matter.

In 1987, we experienced something similar to what took place in 2003. Lithuania was still part of the Soviet Union when our Žalgiris basketball team beat the Moscow Sports Club in the championship finals. Then, too, we united in solidarity, this time in our hallowed hatred of our Russian overlords. But the fervor didn’t last. Once the games ended, life sank back into its usual apathetic shuffle, and we all lumbered in step with the principles of an “advanced socialism”—to be stirred into antipathy against the Russians only on those occasions when the line for oranges got too long.

Whether Europe’s champions will, in the final accounting, be “saved” won’t be the result of their victories on the court. Same goes for the rest of us and our own small triumphs. Nor can love of fatherland be mass-induced. I even doubt whether gold medals will do anything for our national self-esteem or advance our prestige abroad in countries where locals are advised to call their police whenever they see a car with Lithuanian license plates in town. I can even see writing off the entire 2003 championship season and everything associated with it as just another display of the ancient formula for keeping the civic peace through “bread and circuses.” With “circuses” being more satisfying, at times, than “bread.”

But—for me—what really puts the kibosh on “bread and circuses” as the sole explanation for the country’s basketball psychosis is the concept of the Incarnation. In its December celebration of that sublime “mystery,” the world sinks into a morass of baubles and trinkets. Surely, all that fuss and hullabaloo over evergreen trees decked out in tinsel and lights is no more “spiritual” than this year’s sports carnival (which I am far from denouncing). Nor do I condemn the revelry at Christmas. What other option have we got? We have no other means of paying tribute to the irrational, preposterous, untenable pronouncement that God became a child, that He loved us beyond “rhyme or reason.” There is no parity between us and God, no human display of gratitude that is commensurate with the Gift bestowed . . . I’ve been driven round the bend myself at Christmastime, surrendering to reindeer, elves, and all the rest as a way to deal with what is otherwise inconceivable. The essence of Christmas is simply too monumental for us to contend with. Even St. Francis lost his bearings—like a school boy still wet behind the ears—trying to deal with that “loaded” but unknowable revelation. At its core, Christianity is not about sin or indebtedness. It is about joy—an overflowing, spilling-over-the-riverbanks joy—that has no moral premise or rational foundation.

Granted, all that noise and ballyhoo may not have been a display of patriotism, but neither can it be dismissed as nothing more than mob frenzy. In fact, I recall a sermon by a leader of the Anglican Church pointing out that God wants the yearning heart, one that can feel an utterly irrational and gratuitous pleasure in His creation; that God’s gifts to us, like art and beauty, ritual and music, are of no practical or material value. They exist simply to set our joy free.

It isn’t often that people find themselves experiencing transcendence. Television reality shows and stage productions do draw massive crowds, but what is on display is the exact opposite of joy: it’s an admission in hysterically raised voices of its absence from people’s lives. Lithuania has had its share of painful convulsions and continues to tremble with them. These days happiness—or rather its substitutes—has taken up residence with the rich, the landowning classes, and, yes, maybe a handful of the Faithful, whose degree of joy proves to be greater than their misfortunes, their low spirits, their poor health, or their empty pockets.

So where should we suggest the nation look for joy? Even the Church, overwhelmed by its many challenges, is incapable of smiling benignly on its flock or rousing them to merriment or simple gladness. What can dispel the darkness in the lives of our worn-out, impoverished, and disillusioned citizens? “The least of these,” the Bible called them at a time when kings considered it their holy duty to protect and defend the poor. Here, too, campaign promises are made not to abandon them. But the promises are forgotten once power and money are obtained.

On September 15, 2003, we saw the least and the lowliest of our people exuberant in their joy. In ways that might seem short-lived, uncultured, and ridiculous. Still, it was joy—the joy of God’s children, the happiness of ordinary people, breaking through the scandals of corruption that assault them daily over the airwaves. It was their chance to transcend, even fleetingly, the unrestrained greed and venality of their government officials, who continue to clobber the life out of them.

Which brings me to another date that was particularly momentous for me. It was the summer of ’86—a mere five years before Lithuania, finally, broke free of the Soviet Union. I had just returned to Vilnius in high spirits after an extended stay in foreign places. My hope of finding the same kind of growing dissent at home that I’d encountered in other Soviet republics, however, was quickly dashed. I found nothing evident in Lithuania that had the potential to muddy the seemingly tranquil waters of Soviet life. To cheer me up, someone suggested a concert at the sports arena: I think it was the rock group Antis that was performing that night. As soon as I walked into the auditorium, I felt what I had missed on the street—a change in the air. The yellow, green, and red stage lights hinted at our national tricolor. During intermission and in the spacious restroom, I encountered an exuberant group of adolescents shouting, laughing, happily jostling each other. I stood there stunned. A miracle was unfolding before my eyes. These were not the staid and docile children of my childhood. I was looking at the force and energy of a liberated gladness. Here, and not at a meeting of the Freedom League did it become startlingly clear to me for the very first time that the Russian empire was indeed doomed.

Happiness is a dangerous thing, a force to be reckoned with. It can overturn more than a telephone booth. That’s why some will say that ground which has been “lost” to happiness will need to be repossessed. Once more, there will be talk of single-minded attention to work, of setting goals and pursuing them with dogged determination, of maintaining an unwavering belief in our ultimate success. Others will suggest the European Union align itself with our basketball players. School children will be offered a fresh crop of “saints” to emulate. All this is well and good but no longer persuasive or sustainable—any more than that earlier promise to restore the symbol of the nation’s integrity and statehood. A nation finds its defining moments—its pivotal words and life-changing symbols—in forever new and different places. And it celebrates its solidarity wherever and whenever it experiences a free and unfettered joy.