Warsaw, Przyczółek Grochowski, (c) The archive of Oskar Hansen, MASP.

Warsaw

Przyczółek Grochowski

Sometimes I picture him coming here. He gets off the bus in front of the pavilion. He carries a cane, wears a fur hat. It’s winter. That’s how I imagine it. He walks cautiously down the path next to the library then passes the preschool. In a maze of cars parked any which way he patiently picks his way through. He doesn’t say anything, he simply observes. Sniffs the air. It’s freezing outside. The sound of snow crunching underfoot.

He crosses over to the apartment block and everything falls silent. He looks at a sandbox converted into a flowerbed, dried stalks jutting from the ground.

I imagine it being Saturday and the people in the housing development getting ready for lunch. The smell of home-cooked food wafts through the galleries; somewhere tableware clatters and televisions thrum. He stops walking every fifty feet or so and has a careful look around. Sometimes he clears his throat. Then he enters and slowly makes his way up to the third floor and along the passage to my door.

I imagine Professor Oskar Hansen knocking on the door to my apartment in the Przyczółek Grochowski housing development in Warsaw. I open up; he says:

“Hello, Mr. Springer. I received your letter, and I’ve come to explain. You’ve got it all wrong.”

Then he walks in.

I’m imagining all this because it would make everything much easier. During my first night at the Przyczółek I had no dreams. And maybe it’s better just to accept that this is one of those places where dreams are impossible. A hell.

One of the residents calls me:

“I found your flyer in my mailbox. So, you’re writing about the Przyczółek. Are you blind? What more do you need to know? This whole stretch of land between Saska Kępa and Grochów has been ruined. It’s good the two of them are six feet under now and can’t do any more damage. But I’ll tell you this much, don’t waste your time, or that of other people—write about something else. There’s so much to write about, but here you had to pick the worst housing complex in Warsaw.”

A letter from another resident signed with only her first name, Bożena:

“I’ve lived at the Przyczółek Grochowski for forty years, and I think it’s an architectural disaster. Not just the facades, but the floor plans, too, leave a lot to be desired. Someone decided to put in loggias, but they forgot that Poland’s climate is a little different from Italy’s. The wind blows something fierce between the buildings and dust gets in your eyes, and it gets in the windows, too. The way the apartments are designed is awful. A 600-square-foot apartment with a 20-square-foot bathroom and 30-square-foot kitchen (four and a half feet wide!), and the room measures six and a half by twenty-two feet. The only plus is the two lakes nearby, and there’s quite a lot of greenery around. The whole time I’ve been here I’ve always thought the people who designed this project should be forced to live here, too. As punishment.”

Zofia and Oskar Hansen, family archive.

Zofia Hansen: “You live there? Is that true? A terrible idea. I’m so sorry to hear it.”

The Przyczółek has been in the movies, always playing the drab background to some whispered intrigue. Most recently it featured in the TV series Bouillonaires (Bulionerzy). A family of four living in a one-room flat, parents on the sleeper sofa, the nearly adult children on military cots or who knows what. When one of them snores too loudly everyone wakes up. Vicious in-laws living next door. The neighbor downstairs who vents her frustrations by flogging the radiator. Despair, or laughter mixed with tears. In a contest organized by a bouillon cube manufacturer the family wins a fortune. The Przyczółek is the hell they escape on their way to paradise.

“You can’t even die here in dignity,” I overhear someone say on Bracław Street. “You can’t even get a coffin in and out of the apartments. They have to wait with it downstairs. The sexton wraps the corpse in a sheet and shoves it out the window. I saw it happen once. They were carrying a dead man. His hands were dangling. No dignity at all, but how else are you going to do it? That’s why all the furniture people have has to be collapsible.”

My furniture, too. I once purchased a bookshelf and a desk, and asked at the store if they could deliver it. A few days later I stood in the window watching a car with my things in it weaving its way through the development, the guys in the front seat had a look of madness in their eyes. An hour later they knocked on my door.

“What idiot designed this joint? We’ve been schlepping your stuff up and down the whole complex.” They frame it as a question, but they probably don’t want to know the answer. And it’s not my place to tell them.

Me: “So you never regretted it?”

Zofia Hansen: “Not Oskar—he was too stubborn to change his views, but I was horribly upset; I couldn’t sleep at night, thinking how miserable we were making people! What a disaster.”

Exactly 8,030 individuals in 2,330 apartments. Twenty-three apartment buildings linked by semi-exposed galleries or loggias on their sides, meandering for a kilometer and a half. It’s one of the longest buildings in Poland.

Andrzej Osęka, in an interview with Adam Mazur, describes it as “a modernist, rectangular residential complex that bears features of a nineteenth-century apartment house enclosing a courtyard.”

Which is utter bullshit.

The litany of complaints begins with the kitchens, which have windows that open out onto the sunless galleries. I have one like that, too. Then there are the rooms (weird), the walls (thin), the gaps in the walls (wide), the corners (rarely straight, improvised), the galleries (cold, snowy, rainy, etc., and you can’t use salt on the ice because everything rusts immediately). And last, right before the “amen”: The development was designed by people who had clearly never encountered evil before.

“Once there was this family that went to church for First Communion, and when they got back there was nothing to serve or feed their guests with: They’d been cleaned out; the robbers even took the chairs,” says Joanna Siwek, a resident of the housing development since 1971. “They broke into our car twice, and one time they stole it outright. They were from here. After we bought a new one our daughter told us to get in, roll down the windows, and drive slowly around the housing complex three times, stopping here and there. Whoever was supposed to be watching, was watching, and they could see the car was owned by locals, so they didn’t touch it. They left us alone after that.”

The Przyczółek Grochowski really is designed as if there were no such thing as criminals. It’s full of niches, dark alcoves, blind spots, dead ends. The ground floor apartments can be entered through simple balcony doors; and the kitchens, regardless of the floor, are directly accessible through the windows to the gallery outside. Making a getaway must be ridiculously easy if you know your way around. All you have to do to shake potential pursuers is to change direction a few times in the labyrinth of galleries and stairwells. Over the years these dubious qualities proved useful to thieves. Burglaries and robberies increased to epidemic proportions through the nineties and into the new millennium. Which is why the residents decided to close the Przyczółek to outsiders. They put up barriers made of iron grilles and even walls across the galleries linking the buildings.

Andrzej Gołowin, forty-year resident of the Przyczółek: “The barriers give us peace of mind. Thieves can’t come in anymore from one side and escape out the other. You have to use one of two staircases. That makes it easier to catch them, even just to notice them. Thanks to the barriers, people have started to get to know their neighbors and they can even tell who the outsiders are. Familiar faces don’t steal televisions.”

“But why did people get to know each other only after the barriers went up on the galleries?” I ask.

“I’ve thought about that for a long time, too. People had dogs and they would take them for a walk. Or else they’d be taking their children to school or daycare, or be going to the store and standing in line there. Those are all places where people can get to know each other.”

“And that has to do with the barriers because . . . ?”

“Afterwards they head back and have to get to their floor by one of the two staircases, not like before, when you could enter from just about anywhere.”

“But maybe it would be more convenient to be able to enter the complex wherever you want? That was the original idea after all.”

“It all depends on what you’re accustomed to. We can talk about it until we’re blue in the face, but I once actually witnessed a group of young ruffians, probably on drugs, jump on top of a car outside my building and break its windows. Outright vandalism. If only they were actually stealing something! And those boys weren’t from around here, they came in from the other end of the complex.”

“But what does that have to do with the barriers on the galleries? They were vandalizing out in the parking lot. They could have come in wherever they wanted, with or without the iron bars there.”

“No, I’m telling you, when there are bars up, they get scared.”

“Of what?”

“I don’t know, but they do get scared. People are capable of doing things like that only in places where they’re anonymous. But I’m not fetishizing the barriers; I think Warsaw has a problem with partitions generally, all these fences going up everywhere. I’ve only ever been to a couple of places where they didn’t have barriers or fences anywhere; but there, when you got up close to something, a friendly security guard would suddenly pop up out of nowhere and asked you who or what you were looking for.”

“But maybe we shouldn’t assume that every stranger we encounter is bad? Otherwise we’ll have guys constantly popping out of nowhere asking us where we’re going.”

“Let me tell you something. All those ideas you hear about freedom are expressed by people who live in walled subdivisions with armed guards to watch over them. But this here is life, and we have to cope with it somehow.”

I ask about the barriers one more time at the Przyczółek Grochowski Residents’ Association.

“If you could write something about us to the fire department or the Buildings Commissioner, about how those iron bars are still there and constitute a hazard, I would repay you handsomely,” says Marek Wilczyński, who takes care of building upkeep for the Association. He continues confiding in me: “Those people are stubborn, they insist the barriers make the place safer, and you can’t reason with them. We live in a different world now, and it’s no different at the Przyczółek, but some people, it seems, haven’t noticed. They hold protests, they write letters. But if I had an order from the fire department to go in and take the iron bars out, I wouldn’t even have to discuss it with those people. I’d just show them the citation on paper, how they need to pull them down or else pay a fine.”

That would be one way to solve the problem! We laugh. A few days later Wilczyński calls me:

“Mr. Springer, I just want to remind you about the barriers. All you need to do is to write something, then we can take them down, and the problem will be solved.”

Zofia Hansen: “But that’s what we designed their society to look like.”

Professor Wiktor Gutt, a student of Oskar Hansen: “By a fluke I happened on film footage of Hansen being confronted by residents of the Przyczółek Grochowski. And that was just one out of many projects he designed. In the film, the residents were very blunt, the way they used to be in those days, and terribly upset. There were outright invectives directed at the Professor. It was a very dramatic conversation, a real confrontation. The residents felt like they’d been shafted; they said it was a scandal. But the Professor was so calm and matter-of-fact in explaining himself. You could see that he and the residents lived in two different worlds. It was all highly fascinating. I had never heard of this person named Oskar Hansen before, so I decided I had to meet him.”

The summer house the Hansen's built for themselves in Szumin, in accordance with the ideas of Open Form, family archive.

Oskar Hansen’s book Towards Open Form was published in 2005. In it he addresses the Przyczółek Grochowski and its problems:

“The public space-time I’m talking about in the interview no longer exists . . . Grilles put across the galleries undermined its functional-cognitive continuity, and the wire fences and ‘hedgerows’ of the ‘private’ gardens destroyed the free leisure space that had been created with such difficulty . . . The bars and barriers have divided the integrated, friendly space into an unfriendly, disintegrated space that is conducive to aversion between people and anti-social behaviour.”

In this, his last public statement, the Professor proposed resolving the residents’ problems by means that were not even available at the time. The noise of passers-by and running children on the galleries was to be muffled with sound-absorbent mats; doors could be prevented from banging shut by means of photocell-operated automatic door closers; peeking into people’s apartments from the galleries could be prevented with one-way windows, and vandalism deterred with the help of security guards.

“These inconveniences won’t be dealt with by putting bars across the passageways,” the Professor concluded.

Lucjan Nowicki, who for many years was a member of the housing development’s board and now sits on the Association’s audit commission, invites me to meet him in his office. We can have a chat.

“It would all work out if someone would just keep these people in check, you know, a kind of Angel. Remember Alternatywy 4? But there aren’t any Angels here and there never were.”

Oskar Hansen again, in his last interview: “People came to the Przyczółek prejudiced, and they got something other than they expected. They were disappointed because their dreams didn’t come true. But does that mean that an architect shouldn’t propose anything that the people aren’t used to? That’s the fundamental question. And, above all, it’s a moral question.”

Paris

On the Trocadéro some men with scarves around their necks launch colorful flying tops into the night, betting that the people whose heads they fall on will want to buy them. But nobody does. The people just watch the blue lights buzzing up into the sky then go their separate ways, despite the calls and entreaties coming from the men. It’s cold and windy, the juncture of October and November.

A day later on Place de la Concorde: commotion and sunshine, a few people, pretty girls who keep looking straight ahead. I remember something he wrote:

“Leszek and I once made our way to the center of Place de la Concorde. It was late afternoon. We stood with our backs to the Tuileries, surrounded by swarms of automobiles driving in circles around the plaza, fascinated by the sight of all that simultaneous motion foregrounded against the rising slope of the Champs-Élysées. The setting sun was caught between the columns of the Arc de Triomphe, illuminating all of the vehicles and thereby creating an immensely powerful, unified spectacle, like streams of flowing lava. It seemed to us then, us provincials, that we were standing in the center of the modern world.”

I’m having the same feeling. I have to close my eyes because everything is too bright and overwhelming. And the feeling of not being from here and of seeing everything. Or rather, the feeling that I come from there, that other place. Even if the difference isn’t as large these days as it was then. When he asked them for something to drink, they put a bottle of vodka on the table because they thought those crazy Poles drank nothing else. Unfamiliar with the spices in a Chinese restaurant, he put too much of something or other on his food and thought he’d burned his tongue for good. The feeling of incongruousness must have been much greater then than it is now. But even now it is intense.

He came to Paris in order to confirm his beliefs, that he was right. He had seen an announcement for a French government fellowship for young architects posted to the same notice board where he’d first met Zosia. He sent in the documents although he had no expectations of succeeding—he was not a member of any youth organizations and was still unsure how much of his past life as a partisan had followed him to Warsaw. But to his surprise, he got it. Krystyna Bierut, daughter of the president of Poland and a friend of Zosia’s during the occupation, had helped. As soon as he received the news, he sent her a telegram with his arrival information. She happened to be in Paris on vacation at the time. For frugality’s sake he signed only his first name. At the embassy, they thought it was the political economist Oskar Lange informing young Miss Bierut of his visit, and they arranged for a delegation, with a car and a bouquet of flowers, to wait at the station. On 1 October 1948 he arrived at Gare de l’Est, and there he was.

Now, however, Oskar was feeling a bit daunted. He sat at a table in front of two small, perpendicular walls. He was supposed to arrange them so they would stand as close as possible to each other while at the same time preserving their distinctness as separate forms. It was part-exam, but part-experience as well. He positioned the blocks and waited. Pierre Jeanneret, a long-time collaborator and a cousin of Le Corbusier, came to his table. He did not look particularly important; he was short and slight, gruff in manner, tight-lipped. With a small ruler he measured this or that, looked at the composition from various angles, and nodded his head in approval. Oskar was admitted.

He got the low-down on Jeanneret from Jerzy Sołtan, who had started working for Le Corbusier in 1945.

“It’ll be better for you if you work with Jeanneret; here all you’ll see is Corbu’s back,” Sołtan said when Oskar asked him for advice on choosing a workshop for the fellowship.

Oskar stayed at the Hotel l’Epoque on rue Saint-Charles in the Quartier de Grenelle. But he did not spend much time there; he wanted to get to know the city. He loved the Paris métro, especially its “crooked, seemingly random, and occasionally awkward form.” It seemed true to him, completely organic. At the beginning, however, the enormity of the city was overwhelming. He spent the first few weeks feeling lost. In a letter to Zofia he wrote:

“I want to show you Paris the way it is, and not the way I used to dream about it. Imposing and intimate, extravagantly sensitive, politely brutal, overcrowded and lonely, joyous, but sad. Opposites that excite and spur each other on. The most amazing works of art are here—right up against the ugliest, tackiest, and most tasteless kitsch.”

In a cafeteria on Boulevard Saint-Germain he met the sculptor Alina Szapocznikow and the future art historian Ryszard Stanisławski, the painters Ludwika Pinkusiewicz (Lutka Pink), Kazimierz Zielenkiewicz, Jerzy Kujawski, and most importantly Lech Kunka, who actually lived in the same hotel. Soon Hansen and Kunka were embarking on day-long adventures in Paris’s museums. They usually went together, but visited the exhibits independently of each other, avidly sketching and taking notes. From time to time they would meet up and exchange observations, then go their separate ways again, each to a different corner. They spent the bulk of their time at the Musée de l’Homme, leaving only when the security guards asked them. Later they would talk for hours. Kunka knew far more about art history than Hansen and sometimes gave him lectures lasting hours. Wandering the Paris streets together, they were constantly amazed at the smiling faces of the passersby. Some time later Oskar recalled their astonishment: “Eventually we realized just how sad we were and how sad Polish street life was.”

They had little time to engage in all the pleasures of big city life, however, as their days were taken up with obligations for the fellowship. Oskar was improving his French in a course for Poles at the Alliance Française, and his work for his mentor took up much of his time. Jeanneret was demanding, but kind. He gave Oskar his first commission, a set of perspective drawings for an aluminum-frame house. Oskar decided to draw a blonde woman with a braid in the foreground—purely for compositional purposes; her figure was meant to lead the viewer into the picture. Jeanneret liked the drawings, according to Oskar, because you could see that a Pole had made them. The client, however, had a different opinion. When Jeanneret showed her the sketches, she expressed her anger and left the room, slamming the door. The workshop lost the commission.

Oskar’s museum visits led him to think more seriously about painting. He talked about it with Kunka, and it occurred to them both to visit the studio of Fernand Léger. The great painter not only received them, but agreed to their pursuing a long-term apprenticeship with him. Trembling in his boots, Oskar spoke about the matter with Pierre Jeanneret, who in response to the name Léger merely nodded his head in agreement. From then on Oskar spent three days a week at the drafting table in the workshop on rue Jacob and the remaining two in front of an easel in Léger’s studio on Place Pigalle.

“From Léger I learned that painting doesn’t have to involve torment, that it can be fun, a beautiful adventure and not the torture chamber it was for Van Gogh,” he confided years later.

Carried by their enthusiasm, Kunka and Hansen decided to step up their offensive and visit other major artists. They succeeded in visiting the studios of Victor Brauner, Auguste Herbin, and Albert Magnelli. When they shared with Magnelli their observation of space-time elements in his work, his eyes widened in astonishment. However, all of these visits, no matter how instructive they were, were nothing compared with their unfulfilled dream of calling on the most important studio in Paris. This one was located in an impressive edifice on Rue des Grands Augustins, the first floor of which was inhabited by a painter whose work they both knew intimately, Pablo Picasso. Twice they were sent away empty-handed from his door. But in the end they made use of Polish contacts who had met Picasso during his visit to the World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace in Wrocław. One path led through the architect couple Helena and Szymon Syrkus, but it proved to be a dead-end. Then the indispensable Zofia came to the rescue again. Through a friend of a friend they learned that when Picasso was in Poland he developed a sweet tooth for Wedel tarts and that he had expressed his predilection in letters to Polish acquaintances. Soon Kunka and Hansen received a package from Warsaw containing a suitable letter and a fine chocolate delicacy from Wedel. They set off on their final attempt. Once again they knocked on the door they had come to know so well. They announced that they had a package to be hand-delivered to the master. They were invited in and asked to hand it over, which they did, although with some trepidation. This was soon dissipated, however, by the appearance of Picasso himself at the end of the hallway. The painter read the letter, then gave the two students a friendly hug. He led them, struck dumb with happiness as they were, into his studio, where they talked for a long time. Oskar asked Picasso if he could see the portrait of his son in the baby carriage, having seen only a black-and-white reproduction of it. Picasso agreed and from among dozens of canvasses stacked against the walls, he pulled out the painting in question. Oskar looked at it elatedly, then right away asked:

“Isn’t there some other way you could be painting your subjects? I always see the fourth dimension, time, in your work. But your images are always two-dimensional. It must be tiring, this constant thrashing about between the four corners of the traditional picture surface.”

Picasso looked at Oskar, a little taken aback, and asked him:

“Are you a painter?”

“I do my best.”

“Please, bring me one of your paintings.”

The visit came to an end after a few hours. They never went back; Oskar never took one of his paintings to him.

“I never took Picasso up on his invitation of a second visit because of my own stupidity . . . I realized that I know much more about painting than I’m capable of in practice.”

On 12 April 1949, Oskar Hansen celebrated his twenty-seventh birthday. Pierre Jeanneret had a present for him. He invited him to dinner with his cousin, Le Corbusier. Oskar was surprised and a little dismayed; for all of his previous meetings with great artists he had studied their work beforehand. And although he had managed to collect over the previous few months almost everything the great Corbu had written, the books were still waiting to be read. Today he would have to wing it.

The master architect was waiting for them in his apartment, together with his wife and a friend visiting from Switzerland. Their wirehaired dachshund weaved in and out between their legs. They sat down at the table, drank coffee; the conversation turned to politics. Oskar meanwhile was absorbing every detail of the interior that Le Corbusier had designed.

“I realized then that I was seeing a new world, one created by means of different spatial relations. I was thrilled by the synthesis, the unity of forms and the compositional clarity of their combination: Instead of a window the light source was a glazed surface, white barrel vaults reflecting light; the boundaries of the “house” were living walls made of stone and screens displaying images; and the living area was a continuous floor made of modular squares. The general impression was one of continuousness, like a single-space house.”

After dinner Le Corbusier took Oskar on a tour of his home and showed him his work. The stopped in front of a canvas hanging by the stairs. He told Oskar to have a look around at the interior, then took the picture off the wall. That simple intervention changed the atmosphere in the room.

“I’ve hung this picture here as a way to spatialize the interior,” Le Corbusier explained.

“But it doesn’t spatialize it, it merely livens it up,” Oskar corrected him involuntarily.

Later they went to his studio. Le Corbusier showed him an unfinished tapestry. Oskar was nonplussed and disappointed. He wrote:

“To be honest, it saddened me that even He had been taken possession of by commercial hysteria, He, the creator of the “white houses” that I had dreamed about as a child, the cofounder of “purism” in architecture. I couldn’t reconcile Le Corbusier’s humanistic statements with the way works of art were reified inside his home.”

Just before the visit was over, Le Corbusier pulled out a file of photographic prints that showed different stages in the construction of his Unité d’Habitation, which was then being built in Marseille. Oskar flipped through the photographs rapaciously, grilling the architect on the details. But they had to leave. He promised himself that he would travel to Marseille that summer to see the housing development with his own eyes. He left Le Corbusier’s home with mixed feelings.

It took many years before he was able to write about the complex of feelings he was having. He spoke about it in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist:

“I had read and heard many things about the Parthenon, the Acropolis, etc., but when I actually went there, what I saw was beyond my wildest expectations. I understood there were no words that could describe it . . . I was unable to leave. It was an incredible experience of space-time: at sunrise, at noon, in the evening when the people come and walk around . . . ”

“The point of reference that I use to measure Picasso is the Parthenon, because it’s something that can’t be adequately described . . . Le Corbusier in turn, to continue the metaphor, is like the Hagia Sophia. Why? Because I expected a lot from the Hagia Sophia. But when I went there for the first time, I didn’t find what I had expected. Only when I returned later . . . did I recognize the true value of it . . .”

“Picasso . . . taught me things about life, whereas Le Corbusier was a great specialist, a man of great talent, perhaps even a genius, but he did not give me what Picasso did . . .”

Paris in November is so perfect I can hardly believe it. It’s cold again; again the sunlight is harsh. The boorish waiter in the Quartier Latin, the bookstores on the Boulevard Saint-Germain, the cafe chairs set right out on the sidewalk so it’s hard to walk past. Vendors selling Chinese knock-offs, used insert CDs from magazines, shoelaces, and miniature Parisian buildings cast in clear plastic, all laid out on sheets of cardboard. But as soon as they spot a police officer they roll it all up and disappear. Rue Mouffetard: He lived somewhere around here. He mentioned similar street vendors, though they probably weren’t African, maybe Algerian or Arab, how would I know. They spread out their wares on the street; you have to be careful walking past so you don’t step on anything. “The street was a genuine Open Form, a true gem . . . it was authentic space-time,” he said.

And then the métro, first one, then a second, then a third. A guy sleeping standing up; a woman with a white puppy. I take a picture; it comes out blurry. The airport in Beauvais; we stand in line at the check-in. At the gate next to us they’re heading off to Cluj, Romania. I wonder what it’s like to return from here to Cluj.

I wonder what it was like back then to return from here to Warsaw.

Bergamo

“It’s hard for me to believe that the founder of the new architecture, one of the founders of purism, thinks it can be humanized through textiles—products intended to be bought and sold. As far as I can tell, the whole so-called renaissance in French textiles was a commercial enterprise invented for the accumulation of capital, one that seduced and exploited great artists . . . The architects of CIAM should resist this trend and pursue the humanization of modern architecture by its own means . . . .” Oskar’s voice boomed through the mic, his words directed at the man who a few months earlier had hosted him in his home, treating him to dinner, showing him his drawings. When Oskar was done, the hall exploded in applause. Le Corbusier, listening in silence until that moment, clapped along with the others.

Pierre Jeanneret had invited him here, or rather, he recommended that Oskar head to Bergamo for CIAM’s seventh congress, to listen in on the conversations about contemporary architecture. Oskar took his suggestion, although he was unable to afford the trip. When he left for Italy, he didn’t have a cent to his name. So he slept in the park, washed in a fountain, and lived on bread and grapes. When Jeanneret complained to Oskar about his hotel during one of the breaks between panels, then asked him about his own accommodations, Oskar replied that he’d “managed to find something cheap and comfortable.”

His public appearance was a bit of an outburst. He had not planned to speak, but lost his cool during Le Corbusier’s talk about tapestries and their utility for architecture. He asked if he might say a few words, walked up to the rostrum, said what he thought, then walked back down, semiconscious, probably unaware of what had just happened. He, Oskar Hansen, a man out of nowhere in a tattered blazer, who when the proceedings were over would head off to sleep on a bench in a nearby park, was deaf to the applause. Moments later, Jacqueline Tyrwhitt invited him to take part in CIAM’s Summer School in London. Oskar accepted, although he had no idea how he would get the Polish authorities’ permission to travel to England.

London

They asked him if he knew English. He told them: no. They asked how old he was: twenty-seven. They asked when he’d got his degree. He explained he was still in his third year of architecture school. He could tell from their faces that they didn’t believe him. They insisted he must be a communist ideologue. Oskar had no idea what to tell them.

These were the British journalists. They came to hear the jury’s decision on the best projects of that year’s CIAM Summer School in London. It was July 1949, and Oskar had already had quite enough of England.

He arrived almost two weeks late, the British embassy in Paris having balked at issuing him a visa. At the border, when they caught sight of his cardboard toiletry bag, they hauled him off to be interrogated. They examined his passport under a magnifying glass. They asked him where he was going and what for. But it was all laid out in black and white in the letter he’d gotten from London. In the end they let him in.

He enrolled late in the program and was offered a choice of projects: housing development, office building, transportation center, or theater. He chose the complex, and worked on his own, although the others were working in groups. He drew nine white buildings situated around a “social space” containing two preschools and a public park. Outside, he placed a school and pavilions for goods and services along with car access roads. He succeeded in completing his work before the deadline. His last, free day was dedicated to visiting London, mainly galleries and museums.

When the jury’s decision came, he could hardly believe his ears: honorable mention. According to the jurors, he had got it for doubling population density in the housing development while retaining its “high use values.”

His project made a huge impression on Ernest Nathan Rogers, who immediately offered him an assistantship at the Royal Institute of British Architects in London. The doors to high architecture (and big money) were thrown wide open to Oskar Hansen. But he had decided to return. Rogers was astonished: “Do you understand what you’re going back to?” he asked.

Oskar understood. He explained it to the Englishman as simply as he could: “I’m going back to ruins, and they’re waiting for me,” he said.

Rogers shook his head in amazement: “What you’re proposing to do is an impossible task.”

But that’s exactly what Oskar still did not know.

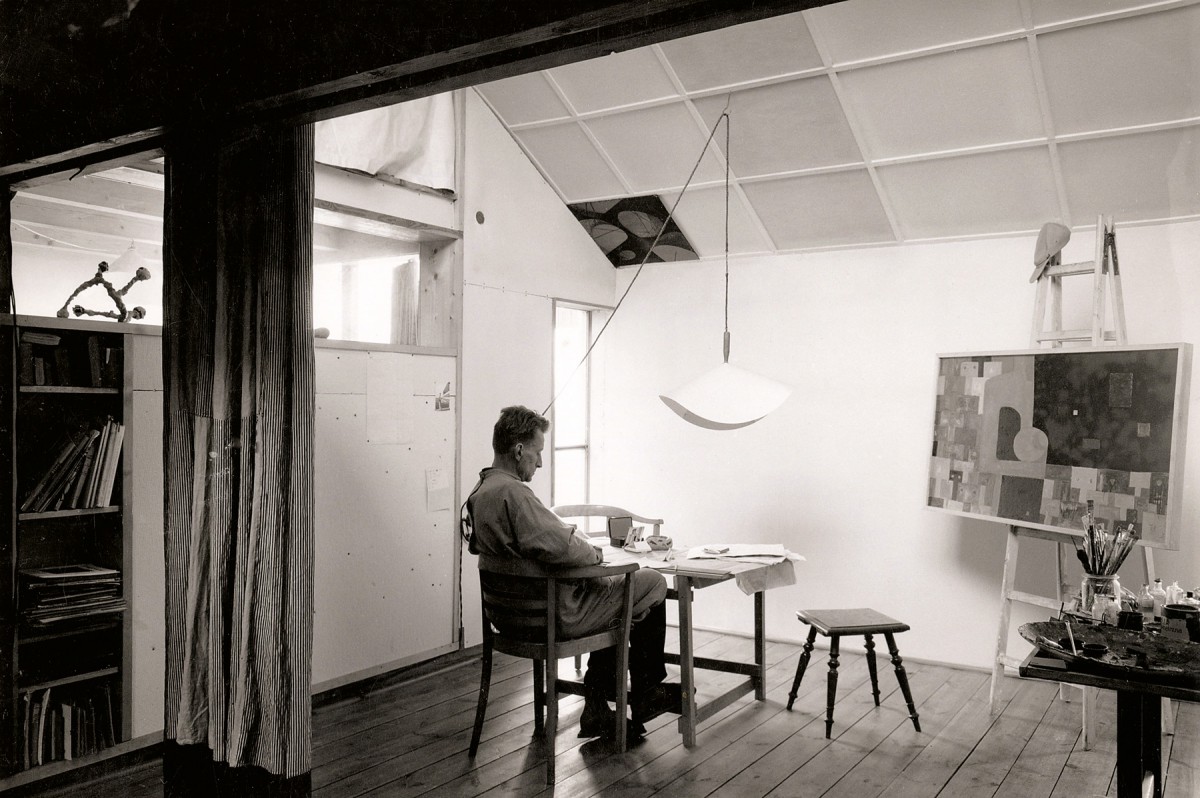

Oskar Hansen in his flat in Warsaw, ca. 1955, photo (c) Edmund Kupiecki, family archive.

Oskar Hansen in his flat in Warsaw, ca. 1955, photo (c) Edmund Kupiecki, family archive.