Circus © Christina MacSweeney, 2005

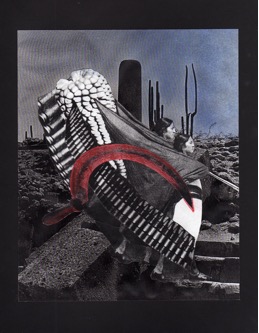

The gunfire from the 1910 Revolution can still be heard. Women wear shawls wrapped across their breasts, where they previously wore cartridge belts. Their strong walkers’ legs forge paths. They try to tame their manes and braid their loose hair. They are still made of earth and water, the maize formed their teeth, straightened their bones, strengthened their skeletons, shaped the structure of their high cheekbones. The sun still outlines their faces. Through their blood runs Zapata’s cry: Land and Liberty. When they arrive in a village they have the fire lit in a moment, they throw stolen chickens into the pot of boiling water, cook them on the points of their bayonets, their rifles on their shoulders so that no one will stop them feeding those who follow behind.

They are the vanguard.

The women walk, sweat, make love, they offer their swollen bellies as pillows, they give birth and grow used to death. Each one has her dead inside her. The only female writer of the Mexican Revolution, Nellie Campobello, recounts in Cartucho how she falls in love with the bullet-riddled corpse beneath her window—her dead—and misses it when it is taken away. They don’t cry, no one cries, there is no compassion, it is not the time for prayers or vigils. The only things that matter are the bullets.

They Are the Vanguard © Christina MacSweeney, 2005

In the twenties women are free because they are themselves. They do whatever their instincts dictate, they do not make pacts with society, religion, or the law. There is no great difference between their inner and outer worlds. They tread firmly, click their heels, they are floating flower stalls, colored banderillas, fairground horses, musical chairs. They pass through life as their own champions. Lupe Marín, Diego Rivera’s wife—a tall thin virago—breaks his pre-Hispanic idols over his head and serves him a rich soup of shards when he fails to give her housekeeping money. Dolores del Río comes back from Hollywood and exchanges her ostrich feather boas, her aigrettes à la Cedric Gibbons, for a Oaxacan straw hat. After a whirlwind romance, Inés Amor marries a bullfighter called Pérez—yes, Pérez—in Texcoco. Can you believe it? And the wedding feast is two tostadas with mature cheese and a shot of tequila, eaten in the shade of a tree. An Amor with a Pérez, can you imagine anything so incongruous? At midnight, Juan Soriano and Diego de Mesa wake up the whole neighborhood calling ‘Lola, Lola, Lola’ from the street: Lola Álvarez Bravo gets out of bed, dresses quickly and goes dancing with them at the Cabaret Leda. Antonieta Rivas Mercado is the patroness of the Teatro Ulises and muse to José Vasconcelos. In contrast to her saintly aunt, the devout Conchita Cabrera—founder of the Order of the Holy Spirit—the sensual Machila Armida prepares aphrodisiac stews, sautés mortal sins, seasons desires, and holds her drink better than any man. Elena Garro does just as she pleases in Octavio Paz’s life; when he asks her to get ready for a reception at the Guatemalan Embassy, she paints her face black, wraps a spotted Aunt Jemima kerchief round her head and, to her husband’s horror, gets into the official car, broom in hand: ‘Didn’t you tell me to get ready, Octavio?’ At fourteen, María Izquierdo marries the soldier Cándido Posadas and when she paints him, the figure is exaggeratedly large, somber, dressed in dark clothes, menacing. A woman stands waiting behind him. Is it María herself?

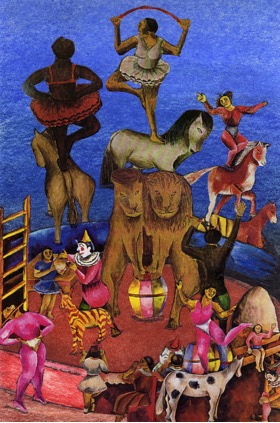

A single circus performance was enough

María Cenobia Izquierdo was born in 1902 in San Juan de los Lagos, Jalisco State, a place of pilgrimage which regularly fills up with the faithful awaiting a miracle. She lived with her grandmother and an aunt, both of them devout and boring, according to Margarita Nelken, the art critic who came to Mexico in 1939 as an exile from the Spanish Civil War. Izquierdo never took part in the annual San Juan festival, when men and women from all over the world gather around the shrine and the innumerable stalls selling rosaries, holy pictures, and bottles of holy water, but the single circus performance she was taken to made such an impression that for the rest of her life she was to paint fairground horses, acrobats, trapeze and tightrope artistes, elephants, jugglers, dancing dogs, solitary zebras, and a lion with his lioness that would give themselves up to amorous incidents if their tamer did not stop them. No one has ever painted horses like María Izquierdo; she sees them so plump and submissive that they would never throw off their blankets, much less their Amazon riders.

María is not only a horsewoman, she is a lion tamer.

To marry, at the age of fourteen, a man who raises a finger in command, as she paints him, is a portent of violence in a country that is itself violent and traitorous.

This is it

On 14th August, 1929, Diego Rivera becomes the principal of the Academia de San Carlos and points out María’s painting as the only worthwhile thing there: ‘María’s work shows neither the simple attraction of graceful improvisation nor the picturesque qualities of good taste, nor that literary departure capable of attracting non-artistic sympathies.’ Margarita Nelken states: ‘Diego Rivera walked straight past the works of the students with the highest marks and, suddenly finding himself before María's paintings, emphatically declared: “This is it.”’

Indignation. Uproar. General protest. The next day the students welcomed her with pails of water. ‘It’s a crime to be born a woman,’ María exclaims in her memoirs. ‘And it’s an even greater crime to be a talented woman.’ In the face of her classmates’ envy and lack of comprehension she decides to work at home.

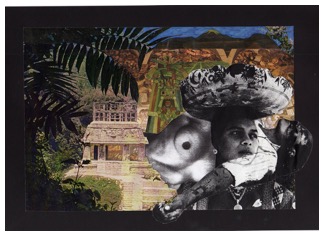

Mexico, Mexico

Mexico is an exploding firework, she radiates light. No one in Europe can remain indifferent to the new cultures hidden in the American jungle. The archaeologists cannot believe the ever-increasing number of pyramids beneath the trees. Mesoamerica could be the Greece of the New Continent. The art of the Maya, crouching like a tiger in the swamps, makes an incomparable impression on them. Jacques Soustelle will never be the same again after Teotihuacán and Monte Albán, nor will Sylvannus G. Morley, Eric Thompson, Edward Seler, Alfonso Caso, or Alberto Ruz Lhullier. Suddenly, Mexicans become admirable, the great Mayan civilisation lends them a certain prestige, an attraction they did not have before. The descendants of such maestros are surely the artists the world is waiting for.

Mexico, Mexico © Christina MacSweeney, 2005

Mexican Muralism dazzles many people and, when the Big Three come to the fore, the movement is acclaimed and the critics announce a new Renaissance of universal arts in Mexico, that is to say, in Nahuatl, the navel of the moon. European and North American artists want to paint alongside the maestro Rivera. Jean Charlot and Pablo O’Higgins are his humble assistants. Two sisters, Grace and Marion Greenwood, are the first women to climb the scaffolding and paint, and what's more, they do it in a market. The writers D. H. Lawrence and Hart Crane, the photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paul Strand, Edward Weston and his disciple Tina Modotti, Sergei Eisenstein and Tisse, his cameraman, all go into ecstasies and Storm over Mexico is the earthly paradise. The 1910 Mexican Revolution not only preceded the Russian one, but José Vasconcelos speaks of the birth of a new race in our country: the cosmic race. In Mexico, the new man is forged, the future of the world is in gestation in our continent, the crossing of the blood of two cultures will be invincible, the energy concentrated in our landscape is the same as that in the neurons of the Mesoamerican brain: volcanic. José Vasconcelos’s Ulises criollo draws a parallel with the Greeks, although Juan Soriano says you'd be better sticking with Homer's version if you want to read Ulysses. The euphoria is endless. No visitor will be able to ignore our grandeur, which not only comes from the past, but erupts in every manifestation of popular culture. Mexico is an enormous market offering radishes and carrots beside the colors and sensations that drive the foreigners crazy.

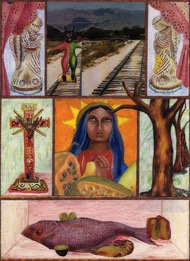

The wonderful huachinango

Finding herself in that maelstrom of recognition, María Izquierdo fills with sap, with fantasies, lyricism, gratitude for this unique country that draws the eyes of the world’s intellectuals. Pleasure becomes an aesthetic experience for women. María paints the fruits she would delight in eating up and, after Manuel Álvarez Bravo has photographed them, she devours the pears, figs, bananas, and mandarin oranges in the dish so they won’t spoil. At midday she cooks the huachinango she has painted.

Mexico is the clearest region of the air, the magical country where nothing is wasted and where nature is, first and foremost, an immense call to art. Soup is made from chrysanthemums, tea from bougainvillaea leaves, flowers are mixed with the scrambled eggs and, in a convent in Puebla, the nuns’ most daring dish is chicken in chocolate sauce. Everything is possible. When bangers go off, Edward Weston thinks they are gunshots and when he hears a round of gunfire, he confuses it with the fireworks of a village festival. What a country! Heavens, what a country! Far from supercapitalism and technology, Mexico is a country where nothing perishes in either time or space, or rots, or multiplies, or becomes banal. María Izquierdo sews her own clothes, doctors her family with wild herbs, she eats up her own work and it does no harm to her stomach.

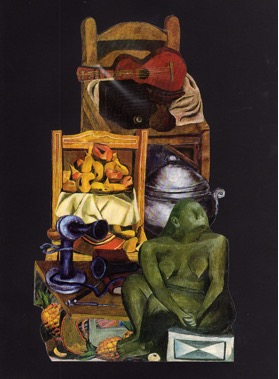

Cupboard (Altar to Dolores) © Christina MacSweeney, 2005

Like an altar to Dolores

María Izquierdo, who used to make her lips up into a cupid’s bow, accepts her wide, passionate, dolorous mouth, a mouth that knows about sowing and reaping. At once wild and courtly, she carries her country in her belly. From Jalisco, the state that gave Mexico José Clemente Orozco and Juan Rulfo, she brings the ochres, warm reds, and golden yellows, the colors of mole sauce, not just the chocolate and black, but also the green, white, creamy yellow and ruddy red. She puts them on her palette and on her face. According to Lola Álvarez Bravo, she devises cosmetics based on ochre and burnt sienna and spreads them on her face, a face she accepts as it is. Other women with Olmec features copy her. With her strong, squat soldier’s body, María Izquierdo adorns herself like an altar to Dolores. Dressing piñatas, making kites, putting up altars, filling cupboards, and arranging flowers on graves are the tasks of brown-skinned hands, and María will play her role until the end of her life. Even when seriously ill, she will repeat her still lifes and cupboards because they are part of lo mexicano, ready for export like the little girls with braids and staring eyes sitting on the flower-painted chairs of Gustavo Montoya, a painter who can’t hold a candle to her. She surely fascinates the Chicanos because there is, in her work, a great deal of the rustic flavor they took with them to the United States, and her paintings look back to the past and homemade medicines: the teas and herbal remedies of the magical grandma who presided over their childhood and never learned English.

The circus

And there is still more. To María Izquierdo, the provincial child who poses so seriously in the dress of striped bars that imprison her, her two legs sheathed in black inside black boots, to María Izquierdo comes freedom. Yes, let’s dance! The rider dances on tiptoe on the back of the horse, the acrobat dances, the lions dance beneath the tamer’s whip, the fairground horses dance, they dance clumsily, their stick-legs don’t obey them—of course, they never did—they throw themselves into the ring, funny, authentic, giving us their very essence, María Izquierdo’s essence. And they do all this with ungainly, artless steps in the oldest, most primitive of spectacles: the circus. Sylvia Navarrete recounts that a herd of wild horses almost trampled María when she was a child, and from that stampede comes her obsession with them. Well, all of us Mexicans have an obsession with horses; remember that, during the Mexican Revolution, they travelled inside the wagons with the people outside on the roof getting soaked, as Jesusa Palancares, the heroine of Hasta no verte Jesús mio, explains: ‘The animals came first. The Indians outside, covered in mud, and the horses inside, covered in shawls, eating tortillas and brown sugar.’

Tamayo, Tamayo, Tamayo

Just as she set spinning her travelling circuses, her wheels of fortune, her fairground horses, María Izquierdo, in her turn, spins like a Catherine wheel. According to Ermilo Abreu Gómez, the parties in her house last two days and the creative artists of the moment turn up there. Rufino Tamayo, the man who sings, paints, plays guitar, wears pink shirts, blue shirts that turn purple, falls in love with her. They live together for four years (1928-32), make love, observe together, paint together in the studio on Calle de la Soledad where the muralist Pablo O’Higgins would later live. Passion passes from one to the other, and from paintbrush to canvas. They do not compete, they complement each other. They choose the same subjects. They share the same obsessions. María Izquierdo’s presence in Rufino Tamayo’s life is so strong that, years later, the pianist Olga Flores Rivas, his second wife, will forbid her name to be mentioned ever again and the world will respect that order.

Tamayo, Tamayo, Tamayo © Christina MacSweeney, 2005

When they quarrel, people who are deeply in love hate each other so much that it’s frightening

‘She was very amusing, really funny,’ says Soriano. ‘She lived a few years with Tamayo and they used to paint almost identically, the same subjects and colors. They were deeply in love but, when they quarrel, people who are deeply in love hate each other so much that it’s frightening. They separated and never so much as said hello again.’

‘María Izquierdo and Rufino Tamayo worked in a second-floor arcade,’ recounts Luis Cardoza y Aragón. ‘There are slight similarities in the work of the two painters during this time, apparent in their treatment of certain related or common subjects. María has the strange grace of great sensibility mixed with technical incompetence. Artaud wrote about her. Soon Tamayo’s talent started to develop and become more polished. Some of his most astonishing works are from that time, oils and gouaches. María died in 1954. They had separated decades before.’

Soriano underlines the odium the two women felt for each other: ‘Olga hated to hear María mentioned. You only had to say “María Izquierdo” and she got in a rage. “That whore. That wretch. That shameless hussy.” But Olga, I would say, María wasn’t a whore. “What do you mean, she wasn’t a whore? She had children and she got mixed up with Rufino.” But Rufino was single then, I'd protest. What was it to you?

‘If they met, imagine it, two angry horses.’

‘María Izquierdo was very important to me,’ continues Soriano. ‘I used to find her very attractive as a woman, very unusual, so small, with those bowlegs of hers, a really sensual mouth and a wonderful head. Have you seen the photos Lola Álvarez Bravo took of her? She was really funny, and then I loved her early painting.’

In his book, Figuras en el trópico, Olivier Debroise says that María Izquierdo ‘achieves her greatest expressive force in the treatment of cupboards, still lifes and small popular altars, through an aesthetic accumulation of objects which allow for the organization of an imaginary yet ideal composition. Her still lifes or circus scenes can be placed within a provincial aesthetic whose roots are to be found in the popular and religious art of the 19th century.’

Following her break with Tamayo, María flays herself. Her painting speaks of the pain that grips her. She undresses her women to better torture herself. Through them, María pleads, howls like a wounded animal. Calvario, La manda, and most of all Tristeza are expressions of her despair.

The dark color of fire

For María Izquierdo, the most important of the travellers is, of course, Antonin Artaud, whom she meets in 1936. He sets her above the others, and María’s work seems to him the only thing, apart from the pre-Columbian art, worth saving in Mexico. In 1947 she will write: ‘I try hard to make my painting reflect the authentic Mexico I feel and love; I do my utmost to avoid anecdotal, folkloric and political subjects because they have no power or poetry, and I think that in the world of art a painting is a window open to human imagination.’

Artaud saw the predominant red in her paintings as the ‘dark color of fire. Her work does not evoke a world in ruins, but one that is remaking itself. […] All María Izquierdo’s painting unfolds in this color of cold lava, in this volcanic half-light. And that is what gives it its unsettling character, unique among Mexican painting: it carries the glimmer of a world in formation’.

Antonin Artaud

But Artaud’s friendship is a nuisance because, on top of not having so much as two sticks to rub together, he drinks and takes drugs. ‘That shortish, boney man with wisps of straw-blond hair and no hat, dressed in white, who used to stand around at any old corner of Mexico City, eyes fixed on nothing in particular, most probably under the influence of some drug or other, and who, when you went up to him, would grab you by the lapel and not let you go until he’d had his say,’ writes Fernando Gamboa. Many a time in the early hours, María and Lola Álvarez Bravo had to go and collect him from some stretch of pavement on which he had thrown himself down, completely lost, ready to die of ecstasy in the low-life areas of the Guerrero or Buenos Aires colonies. Artaud’s stay in Mexico lasts eight months. Neither of the two women understands very well what the poet and dramatist says, but they suspect him to be enlightened. The powers of evil take a delight in tormenting him, they pursue him, want to lock him up in the asylum again. He detects a conspiracy against him at every street corner. Artaud’s three interests in Mexico are María, the sculptor Luis Ortiz Monasterio, and peyote.

The power of the drug is immense, Oaxaca inspires him, the mysterious ‘City of Palaces’ blushing in the sun seduces him, the gods of the past, ousted by Spain, return from the earth and now Tláloc is the god of rain; Coatlicue, with her skirt of snakes, the goddess of fertility; Tlazoltéotl, the goddess of excrement.

For Artaud, María is a priestess, at once both Coatlicue and Tlazoltéotl.

Later, Gordon Wasson and Roger Heim will come from the United States and France to trip on hallucinogenic mushrooms under the tutelage of María Sabina, the shaman of Huautla de Jimenéz in the Oaxaca Sierra; they take them with chocolate, and in pairs: the woman-mushroom and the man-mushroom, the ‘little people’ as the new priestess calls them.

You don’t paint murals, María

In 1945 she began to sketch out a mural for the Federal District Offices, but an evaluative committee, on which sat Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, threw out the project and the contract she had signed was cancelled. María Izquierdo, who had been a member of LEAR (League of Writers and Artists), felt she had been betrayed by her old comrades-in-arms.

There are no female muralists in Mexico except for two North Americans, the sisters Grace and Marion Greenwood, who paint in the Abelardo Rodríguez market. The poet Aurora Reyes paints in a school in Coyoacán and is criticized because, like Tina Modotti, she is a communist and wears overalls. The Mayor of Mexico City, Javier Rojo Gómez, offers María Izquierdo more than 150 square meters on the staircase of the Federal District Offices. María opts to first paint Music and Tragedy, to be followed along the stairs by the history of the arts. She starts sketching to scale and preparing her perspective drawings.

When Rivera and Siqueiros see her project they tell Javier Rojo Gómez that she isn’t capable of painting murals, that her solutions are too elemental.

Not you, María, you can’t do it

María denounces this boycott and starts a debate with Siqueiros. The caricaturist Freyre satirizes the ‘Russophiles’ and draws María Izquierdo with an enormous head and an apron, as la cocinera de la izquierda, the Left’s cook. She had enrolled in the LEAR for the very reason that it put itself at the service of the nation. Rage and bitterness darken her painting. Scorned, rancor invades and contaminates her. Despite the critic Justina Fernández calling her ‘the best contemporary Mexican painter’, resentment finds a place in her heart.

Soriano consoled her, although he thought it very sad to see her walking all pigeon-toed down the street with one of her children, going to sign for her wages at the Ministry of Education. She was no longer giving classes ‘but they hadn’t taken her salary away and she cashed her check every fortnight: a pittance, but she was happy to get it. Even after her illness she went on being warm-hearted and grateful.’

Diplomacy vs. Bohemia

In 1938 María Izquierdo exchanges the bohemian world for the diplomatic one. The Chilean Raúl Uribe—an awful painter according to Inés Amor—becomes her ‘agent’ and, six years later, in Chile, her husband. At the same time as she appears in the society pages of the press, clinking glasses with ambassadors, she paints portraits, cupboards, altars to Dolores, Mater Dolorosas, Naturalezas Vivas (as she calls them), and screens. And she also dresses differently. The French designer Henri de Chatillon makes her fashionable hats. Oh, fashion, how many crimes are committed in your name! Her dresses are black and close-fitting, difficult to put on and take off, and do not enhance her beauty. She and Uribe lunch at the Normandie, instead of the simple Fonda Santa Anita.

Raúl Uribe is a social climber, an opportunist who leads her into the world of receptions and public relations. He teaches María to paint with an ulterior motive: to make money. The one who makes the money is him, the diplomat. The couple’s life is a whirlwind of appointments and activities at one remove from creation: the activities of personal diffusion. María writes on painting in the papers; Antonio Ruiz, El Corcito, Tina Modotti, Andrés Salgó, López Rey and Fernández Leal are her subjects. She gives painting classes, attacks the muralists, and speaks of their infamous monopoly in that field, she caricatures her enemies, stands up for the art master who earns a miserable salary, denounces the indifference, near hostility, of the government towards forms of pictorial creativity that do not follow the maxim ‘there’s no other way than ours.’ She travels to Latin America and, in Chile, Pablo Neruda welcomes her as if she were an apparition.

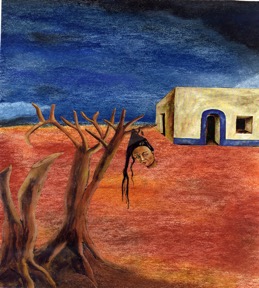

The trees lose their leaves

On changing her status, becoming worldly, laughing at cocktail parties and biting into canapés instead of grains of maize, María’s work also loses its strength. De Chirico enters her painting, the trees lose their leaves, the earth becomes ashen, branches beseech the heavens, spaces empty and the black horizon that unknowingly threatens her, threatening us, defines her work during those years.

María Izquierdo’s houses are cubes, rectangles, squares, planted in the middle of the canvas, as if put there by a child. Their proportions are at once infantile and seductive, the walls are almost elemental. Her portrait of Juan Soriano is sensual and perverse and relates to the nudes of tremendous proportions she made with Rufino Tamayo in the early days. It even seems that she would like to renounce her beautiful indigenous features. The influence of De Chirico, the leafless, mutilated trees, brandishing their wrists at the sky, look like casualties of war. She loses her unfettered strength. There is now something tragic about María Izquierdo. She paints a fruit bowl crowned with pomegranates, grapes, bananas, and apricots, and places it beneath a tormented sky, making us think that it is all going to founder and rot. There is something decidedly sinister, something catastrophic, about her Naturaleza Viva of 1946. With a seashell beside a mammee apple and an avocado pear, it makes us think that Artaud’s notion of her work as a world in formation cannot be applied to all her paintings, because in Naturaleza Viva we witness the only thing left of the world.

The Trees Lose their Leaves © Christina MacSweeney, 2005

‘I used to tell her not to take any notice of Uribe,’ says Soriano, ‘but I never persuaded her because she was so in love with him. In the end she had an attack of apoplexy, was paralyzed down her right side, and he left her. She couldn’t work after that, it was very hard for her, she was in a really bad way. She still did a few paintings, but they were ugly because her friends and family had a hand in them. In the early years we had a great time, were almost happy. Villaurrutia and Agustín Lazo were terribly fond of her, and we lived on the run from one cantina to the next, but all that inspired us because, being young, we would paint better the next morning.’

And the Marxists weren’t so happy either

‘The world of the Left and LEAR was awful. You couldn’t paint what you liked or think what you liked, you had to think exactly the same as them, and so of course it was impossible to have a dialogue because if you think just the same as the next man, and say yes to everything, not a single damned idea comes out of it. In LEAR everyone used to say yes to everything, and they were all under the same influence, I mean Marxism, but none of them had read Marx. In fact they weren't well educated and all said things like “Hey sharpo, you’re twisting me it about,” like Cantinflas, who was a great success because he couldn’t put two words together that made any sense, but it was all so Mexican. I did read Marx and left it off, I’ll tell you why later. The meetings were interminable and boring, they’d discuss how much they were going to charge per centimeter of painting, and if something was good or bad, according to their criteria. They were all jealous of each other, no one liked anyone else, it was a scorpion’s nest.’

The circus girl dances on her toes

On December 2, 1955, in her house in Calle de Puebla, María dies from her fourth embolism at the age of fifty-three. Frida Kahlo had died the year before, but Frida comes back from the dead in the eighties, becomes a totem, a fashion, a craze. María Izquierdo, sidelined by ‘Fridamania,’ is scarcely mentioned, and it is not until the Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo organizes a grand four-month retrospective in November, 1988, with a more than ample catalogue, that María regains her true position within the national and universal history of art.

Everyday and beloved

From then onward María walks again from San Juan de los Lagos to the capital, like an Adelita of the Revolution with her crossed red shawl. Her heart fills her chest, her movements are free, she marches on her strong soldier’s legs. Together with her Mauser, she carries her ochres and yellows, the reds of her red soul and the fire of her passion for colors. She walks with her head held high, does not let herself be beaten, even though she would love to have a horse to take her at a gallop. The force of her will makes her look to the distance, beyond the horizon; she seems to be seeing all her future work, the jewelry box and the fan, the wedding veil on the chair and the soup tureen, the circus and the bathers, the lion tamer and the circus girl, the dancers and the acrobat, the elephants and the small dogs, her simple familiar world, everyday and beloved, that holds out its arms to her and says yes, María, yes, of course, yes, now you can stand on tiptoe on the horse’s back and it will carry you to the space where cupboards merge with altars to death.