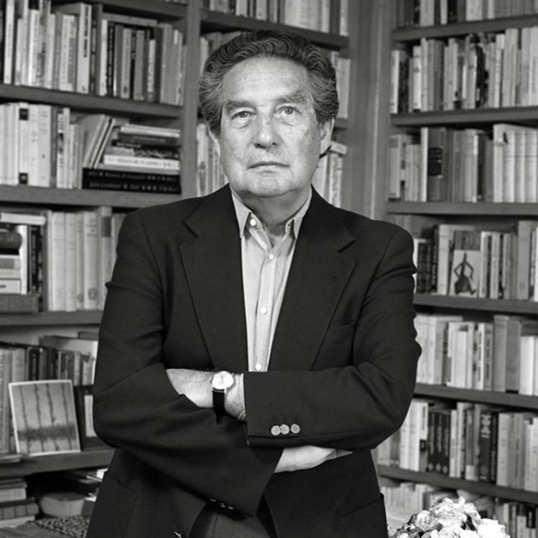

He knows that his temperament has moved between Saturn’s black vision and the momentum of the sun. He knows that he found an answer to discouragement in two of Quevedo’s verses and that those verses became a type of badge to him: “Nada me desengaña / el mundo me ha hechizado” and “mientras salga el sol, hay que bendecirlo.” He knows that when he started writing, people accused him of being too French, too foreign, not Mexican enough. He knows that “one cannot escape old age” and that “one is marked by one’s time and circumstances.” That he has tried to understand and sympathize with young people. That these are challenging times. That what’s missing from books written in Spanish, starting last century, is critical thought. That we live by an abyss. That if panegyrists don’t stop talking about technology and its benefits, they will turn Earth into a desert. He knows all this, and he shares it with me.

Not a hint of hesitation waters down Paz’s gentle voice. He knows that the literary market has no taste and is devoid of ideas. That one of the most chilling aspects of people living in modern society is “our capacity to see what’s happening and our incapacity to put an end to it.” That “frequently we become accomplices to destruction and its spirit.” That modernity “began with critical thought, and today it ends with a widespread numbing.” That there is a way out. “There’s always a way out,” he says. He knows that “memory can be an awful thing; it can take us back to what we don’t want to remember.” That “memory is also a benefactress: it’s beautiful and comforting to relive what one loved, even if it comes in the form of a single image.” Birthdays to him have become “external dates.” He knows that “memory is not tied to a calendar.” That “heroes exist because there are Homers who tell and sing their feats.” That “many write using not ink but bile, and not a pen but a knife and baton.” Paz knows this, he says this, he shares this on the week of his eightieth birthday.

Outside, the tall flowers are not violet anymore, and the night casts tiny shadows on the windows. Looking down, I see the hot pavement. Inside, Paz’s voice names Silvina Ocampo and Adolfo Bioy Casares. He remembers walking around Paris with them and that the Seine “flowed and slid like a peaceful phrase.” He names Jorge Cuesta and remembers that “to hunt an idea, or to fight with a concept, is no less thrilling or dangerous than fighting at a faraway border or facing a bear in a forest.” He names José Bianco and remembers “a ghostly Venice looking like the black-and-white film of a talkie.” He names José Bianco and remembers a feeble smile, a last hug. That’s what he names, what he remembers, what he shares today, a day before the calendar marks the external date of this eightieth birthday.

Towards the end of our interview, after cleansing his words using a sip of apple juice that looked as thick as a glass of molten iron, Paz names Teodoro Césarman. He then calmly flips through the pages of his own El fuego de cada día (Seix Barral,1989) and picks a section of “Entre la piedra y la flor.” So today, when the calendars mark Paz’s eightieth birthday, we don’t wish him a happy birthday because that is an expression flayed by human vileness. Instead, we wish him good health, because that’s the only path leading to something that resembles not happiness—which doesn’t exist—but peace.

In one of the prologues of your Obras completas, signed Mexico, March 31, 1991, you said, “There are as many families of writers as there are human temperaments; some of us are sanguine, others melancholic. Some are introverted, while others are jovial, lymphatic, or bilious.” Now that you are turning eighty, which one are you?

You ask me to do the most challenging thing: to define myself. I’ll try to answer, though. I think that, like any man, I’m defined by fluctuation. In my case, I’m defined by a continuous shift between enthusiasm and melancholy, and vice versa. Others have described this oscillation as being between the black vision of Saturn’s children and the momentum of the sun. My temperament has always moved between these two poles. Nevertheless, I’m not entirely melancholic. I have found the answer to discouragement in two of Quevedo’s verses. These two verses have become a type of badge to me: “Nada me desengaña / el mundo me ha hechizado. El mundo está lleno de trampas, mentiras y desdichas pero es adorable. Mientras salga el sol, hay que bendecirlo. La vida, hay que vivirla.”

I have always meditated, maybe because my melancholic temperament has influenced me. I like to walk away from any external influence and see things with some distance; think about what I see, think about myself. I have always lived this duality: looking in and out; enthusiasm and fall.

Further on, in that same prologue, you said, “When Darío published Prosas profanes, people criticized the book, and many claimed that he was not a poet from the Americas. Since then, a defamatory and worn-down epithet has been part of our conversations. Time and time again, people have accused writers of similar things. First Reyes. Then Borges.” Is that epithet still part of your conversations?

Yes, but the adjectives are different now. When I started writing, people accused me of being “too French, too foreign, not Mexican enough.” I’m not the only one who has been accused of such things. Los Contemporáneos suffered the same type of harassment. Literary patriotism, however, is not as vicious today. Instead, people are ideologically intolerant. For years, people have accused me of being reactionary. They have even accused me of being a secret agent serving American imperialism. These accusations came in the form of anonymous slanders and even physical threats. I was not surprised. When I was young, I saw and heard many—who today are considered saints among Mexico’s left—accuse Trotsky of being one of Hitler’s agents and André Gide of being an instrument of the bourgeoisie. For many years, Stalinism and cultural xenophobia poisoned Mexico’s artistic and intellectual atmosphere. We still haven’t fully healed from those spiritual illnesses. If today’s left—especially the intellectuals—wants to eliminate its old vices and complexities using despotism and ideological dogmatism, it must withstand the critics. Today’s left must learn how to pay attention to their listeners before dooming them.

You say that “we must learn how to listen to the young. It’s a difficult art, and only a few have mastered it. For example, Antonio Machado was a kind and good-hearted man, yet he never did.” Have you?

It’s common for me to fail to see novelty and authenticity in the work of young writers. One cannot escape old age; one is marked by one’s time and circumstances. However, I have always tried to understand and sympathize with young people. I follow what they do with curiosity and passion. If you read the essays I’ve written about Mexican literature, you will see that often I write about writers who are younger than me. In this sense, I think I’m different from writers from other generations. If you check the work of Reyes, Vasconcelos, or Los Contemporáneos, you will find very few references, if any, to young writers. Not with me. Ever since I started writing, I have been interested in not just older writers but my contemporaries and those who came after us. Whenever I find writers who I think are noteworthy, I have saluted them, and written pieces or essays about them, as a sign of friendship and acknowledgment. Some time ago, I also put together, alongside other poets, an anthology of Mexican poetry in which young poets—young then—were considered.

Then you ask, “Can ours be considered modern literature? That question has followed me ever since I started writing.” Does that question still follow you?

Of course it follows me. Every day a bit more.

It’s no secret that what we call “modernity,” for lack of a better word, is going through tough times. We’re living at the end of an era. When I was born as a writer in 1934 (I was twenty years old), the literary movement that had transformed literature worldwide was in decline. But I didn’t know that. In South America, poets such as Huidobro, Neruda, Vallejo, and Borges had come out. In Mexico, we had Los Contemporáneos. Spain had Lorca, Guillén, Alberti, Cernuda. It wasn’t an easy thing to become a writer after reading their work. They were part of a generation that had embodied novelty, invention, and surprise; they were a group of immensely talented writers who had changed poetry and prose. The young writers in Mexico then got together at a magazine called Taller. In Taller, I published a piece, something like a manifesto. In it, I argued that we had to take the great aesthetic revolution of the early twentieth century and make it our own; and, at the same time, that we had to deepen our search for the vanguard and originality and ditch novelty.

In its essence, “originality” means “to go back to the origins.” This idea nourished me spiritually and poetically during those years, and it helped me to start writing. My first small book—quite flawed and written between 1935 and 1936—is called Raíz del hombre, which means “to descend” or “go back” to the origins. I must say to you that I still work under that creed.

You also add that “One of the words that define our century is ‘resistance.’ This word has been more fertile than the other one we inherited from the previous century: ‘revolution.’” Do you think that “resistance” continues to define this century?

To answer your question, I must go back to what I was saying a moment ago. You asked, “Can ours be considered modern literature?” I didn’t truly answer your question. I spoke about modernity in general terms. Now, going back to your question: our literature—and I’m not just talking about Mexican literature but literature written today, in Spanish, across many countries—is modern, yes. Some of its characteristics, however, for better and for worse, take it away from modernity. I find that the only thing missing from books written in Spanish starting last century—since modernity began—is critical thinking. Modernity’s twin is critical thinking, and critical thinking has been the great protagonist throughout modernity’s history, from the eighteenth century to our times. At the same time, our literature has been criss-crossed by the urges of modernity, so to speak. Darío, the founding father of our poetry, wanted to be a modern poet, and he partly achieved it. That’s the tradition of our literature, and I belong to that tradition.

I was born, intellectually and literarily, revering modernity. As Rimbaud said, “Il faut être absolument moderne!—One must be absolutely modern!” Rimbaud’s war cry traversed across literature worldwide, from the end of the nineteenth century to the twentieth century. Like many others, I wanted to be modern. Suddenly modernity, however, after the second half of the twentieth century, started rotting. Many of its foundations have disappeared. Others have cracked. We live by an abyss. I first realized this in 1965.

In 1972, I published Los hijos del limo, which is a description of modern poetry, from Romanticism to the vanguard. But at the same time, it’s a critique of modernity and its idols. For example, of reverence toward the future and the idea that we as men must colonize that future, when in reality, truly, what we must do is colonize our present.

Modernity was founded on the idea of change conceived as progress and, sometimes, as revolution. All of this implies an overvaluation of the future. People in the nineteenth century blindly believed in science. Thanks to science and its development, the future was ensured, and progress was inevitable. Today we know that without physics—the pride of the Western world—it would’ve been impossible to come up with nuclear weapons that can destroy the world and end our species. The atomic bomb represents a denial of the future and a refusal of progress. Now molecular biology, in conjunction with artificial intelligence, studies the possibility of making intelligent artifacts. I think that this is unsettling, to say the least. I say “unsettling,” but I should say “abominable.” Every day we hear people praising technology and its benefits. Its panegyrists forget about the ecological devastation technology has produced. If they don’t stop, they will turn Earth into a desert. We used to think of our Earth as an inexhaustible well of goods and energy. Now we know that the planet’s resources are finite. The relationship between technique and capitalism, moved by an incontrollable search for profit, is the great threat of our time. How can we deny that modernity’s face is the face of death?

All of modernity’s great conquests have two faces, actually. So do democracy’s. I defend democracy. I have always defended it. But I’m not blind to its dangers. Democracy’s gravest danger is the dictatorship of the masses. We clearly see this on TV. TV brings taste and opinion down to the lowest form of thinking. This happens with literature as well. Look at the bestsellers. Any form of art, but mainly painting and the novel, is bound by the market’s laws. As we all know, the market is a machine: it has no ideas, and it lacks taste. Politics doesn’t escape this either. In the United States, people confuse politics with spectacle and entertainment. The old formula used by the Caesars—bread and circuses—can be seen today in the democracies of the more advanced countries.

In my younger days, I was fascinated by the word modernidad—modernity. It served as a type of moral and aesthetic yeast. Today it seems more ambiguous than ever. When I embraced it, I found the chasms in it. My experience, modest as it might be, has not been different from the experience of high spirits such as Baudelaire, Nietzsche, and many of our contemporaries. For more than twenty years, I have tried to use my work to criticize modernity—modernity in art and in literature, as well as in politics and morals. When one reaches this point, somethings baffling happens. When one reaches this point, one becomes a modern man. Critical thinking is an essential element for modernity, and only we, the modern men, can criticize modernity with authority. This is a paradox that condemns us and saves us at the same time.

A paragraph later, you write: “Hamlet still crowds our sleepless nights and our deepest thoughts. He has been neither our saint nor our demon: he has been our mirror and, sometimes, our accomplice.” Is Hamlet still crowding your sleepless nights and your deepest thoughts?

Hamlet is the spirit’s emblem who perceives evil’s slow and invisible work in all things, especially in beloved women. In that sense, Hamlet is profoundly modern. Hamlet is the man who neither assumes evil nor fights against it. Instead, Hamlet hesitates and fights against himself and his ghosts. Likewise, this is one of the most chilling aspects of people living in modern society: our capacity to see what’s happening and our incapacity to put an end to it. On the contrary: frequently, we become accomplices to the spirit of destruction.

At the end of the next paragraph, you write, “In Spain and the Americas, works of art die twice: first they get killed by the envious, and then they die when people forget about them.” Do works of art still die twice?

I think so.

In another prologue from your Obras completas, you write: “I feel part of a tradition that started with the Spanish language. But, at the same time, our language and our poetry come from a great tradition that started with the first men and will not end until our species grows silent.” Do you think that we’re close to that silence?

I refuse to believe that our species will grow silent. However, I’m afraid humans will be muted and bound because of specific threats coming from modernity and our political system. Until recently, the enemies were totalitarianism and the pseudo-revolutionary political tyrannies. Today, other powers try to control humans through technical mediums.

In Mexico, we’re still far from reaching this point. So, when people call us underdeveloped—I particularly dislike this word because I don’t know exactly what it means—I shake my head and pause for a second. Underdevelopment means poverty, inequality, the absence of democracy, backwardness, injustices, and many other material and spiritual iniquities. It’s a relief to know that we’re not entirely infected by modernity’s demon and its selfishness, or its brainless cult for money and easy pleasure, or its fear of death, its superstitious reverence of publicity, its hypocrisy, which hides cold cruelty, its worship of success, its unfairness. Modernity began with critical thinking, and today it ends with a widespread hebetude.

So, there’s no way out? Yes, there is. There’s always a way out. Let’s not forget when the old world and the dark ages ended; the seed of a renaissance ripened in the depths of time. As for us, the Mexicans: we can’t escape modernity. There’s no other path. Our destiny is not and cannot be different from other people’s destiny. But, by walking down modernity’s path, with the rest of mankind, maybe we can walk through modernity itself and go beyond. Not towards an unreachable future, but towards the humble and recurring reality of now. To sum up: we must assimilate modernity if we want to transform it and go beyond it.

Borges once said, more or less, that when people turn eighty, they rarely see people of their age face-to-face, and even more rarely see people who are older than them. Have you experienced something similar?

People frequently invite me to go to other countries. When I go to Paris, I see many empty spaces, and when I go to Buenos Aires, I experience . . . Yes, I think Borges was right. But we can always rely on memory. It’s one of man’s greatest gifts. Memory can be an awful thing, though. Sometimes it can take us back to what we don’t want to remember. But it’s also a benefactress: it’s beautiful and comforting to relive what one loved, even if it comes in the form of a single image. One of literature’s great powers is what we call the resurrection of presences. I’m talking about visions—Joyce called them epiphanies—of certain exceptional and privileged moments. Memory’s mission, particularly poetic memory, is to salvage all that is salvable from reality. Salvation entails a transfiguration. That which we rescue from the past is what we lived and felt, yes, but there’s more: it’s the moment that, without losing intensity, ceases being a moment and survives itself. Time gazes at itself in anti-time’s mirror.

Could you transfigure a birthday with your parents?

No. Birthdays have been external dates to me. When I was a kid, people enforced dates on me. I quickly rebelled against them. I often forget my birthday. María José, my wife, very patiently says to me, “Tomorrow’s your birthday.” Memory is not tied to a calendar.

Now, it would be impossible for you to forget that you’re turning eighty.

Yes. Like when I was a kid, people remind me of it. I’m amazed I made it to eighty. There’s a quote that made quite an impression on me when I was a kid: “Those chosen by the gods die young.” Though I never understood why those chosen by the gods had to die young, I knew that heroes, in general, died young and, naturally, every young man wants to be a hero. As a kid, I was surrounded by the idea of admiring heroes. My grandfather played a part in Mexico’s history. So did my father. They were my immediate role models, but I learned to be skeptical of role models. I once read that someone had asked Alexander, when he was a kid, “Do you want to be Homer or Achilles?” and he replied, “You ask me if I want to be the hero or his trumpet. I want to be Achilles.” I disagree with him. Heroes exist because there are Homers who tell and sing their feats.

In another prologue, you say, “Many modern works of art frequently make me feel exactly the way I feel about this time and age: I feel love and aversion, fascination and disgust.” You wrote this in 1986. Has this impression intensified or lessened?

I already told you what I think and feel about modernity. The ambiguity of my feelings and judgments remains unchanged. It’s the same as with some works of art, novels, and poems: I love them, and at the same time, I dislike them. When it comes to art and morals, nothing is simple. Neither is real life.

In another paragraph from that same prologue, you say, “Almost every book has been written facing society, against society, or facing away from society.” How have you written your books?

Facing away from society. But truth be told, society has always turned its back on me. It’s tough to write in Spanish, especially in a country like ours, where not many people read. Mexico’s literary world is full of envious people. Many write using not ink but bile, and not a pen but a knife and baton. Hostility, however, ends up being an incentive: its admiration’s luck flipped on its head. Indifference is much graver. It’s a hard thing to wake up an ignorant audience that has been anesthetized by television. To pull the audience from its torpor, one must shake it, irk it. That’s why I said that we must write, sometimes, facing an audience or against an audience.

However, I’m not a pessimist. Mexican writers have always had a loyal and intelligent fanbase. I prefer having rigorous readers. We have plenty of rigorous readers in Mexico, and it’s thanks to them that our literature exists. Popular books can be deceiving, and bestsellers have a short life. What matters in literature is endurance. Truly valuable works of art have a long life. People talk about a “reading crisis.” I’m not worried. I don’t know if it's fortunate or unfortunate, but the arts have always appealed to a small group of people. Neither the works of Kafka nor Proust were bestsellers. The works of Dickens and Victor Hugo were bestsellers, yes. But they were the exceptions.

Toward the end of that prologue, you say, “The Maya or Nahua wrote some of the most beautiful poems written in the Americas. I also admire the short and pure chants written by the Otomi.” Have you memorized any?

No. But I’d like to rephrase what I said. Texts written by the Maya are not entirely poetic. They are religious and cosmogonic texts; they’re not truly poems. To find what I’m interested in, in poetry, I think about the poems written by the Nahuas and the Aztecs. Some short Otomi songs did captivate me when I first read them. I think that Gabriel Zaid compiled some of them in his memorable Ómnibus de la poesía Mexicana.

Could you share with us the reason behind some of the people you dedicated El fuego de cada día (The Daily Fire, 1989) to? You dedicated “Arcos” (1947) to Silvina Ocampo.

I met Silvina and Adolfo Bioy Casares in Paris. We immediately became friends. One morning Silvina and I took a walk, went to a bookstore, and had lunch at a restaurant overlooking the Seine. I can’t remember what either of us said, but I know we talked about the reality of our lives and about the books we had read, what we had lived through, and the things we had loved and loathed. We stared at the river on our way back to the hotel. It was the end of spring, and the wind grazed the chestnuts and the poplars. Rocks sunbathed on the ground. The water flowed and slid like a peaceful phrase. I felt that life went by like the Seine, and, much like it, it also seemed to stay still. Movement and stillness. Like the trees on the side of the road, like the passersby and the statues, I turned into an image, into a shadow. And as a shadow, I went into the water and got dragged by its stream. I then disappeared under the arches of a bridge. We walked a bit further down the road, and when we reached Silvina’s hotel, we said goodbye, and I went back to my house. Two or three days later, I remembered the strange feeling I had felt that afternoon: the movement and stillness of a river that runs like our lives. I dedicated that poem to Silvina because it was she—her friendship and her words—who involuntarily unraveled the waters of my words.

You dedicated “La caída” to the memory of Jorge Cuesta.

That poem is made out of two sonnets I wrote in 1940. Much like the title says, the poem is about the experience that I alluded to at the beginning of our conversation: the descent of our consciousness down that path made of mirrors, which forces it to crash against itself, against its ghostly reality, and the reflection of another reflection. Jorge Cuesta died in 1942. Maybe he’d had a chance to read my poem, since it was published in Letras de México in 1941, if I’m not wrong. I dedicated that poem to Jorge some time after. In the book I wrote about Xavier Villaurrutia, I talk about my relationship with Jorge Cuesta and the time I met him. Ours was a literary and intellectual relationship based on a shared passion for ideas and our love of literature. Jorge Cuesta was one of the few contemporary Mexican writers with one of the virtues that I appreciate the most: intellectual passion. You mentioned a book I wrote some time ago, Pasión crítica. Well, critical passion is nothing but the derived form of one’s passion for ideas—which, I think, is essential to the life of a person’s spirit.

Man’s highest aspiration is the contemplation of truth, which is, like Plato taught us, a contemplation of beauty and goodness. Almost always, intellectual passion and the search for knowledge are solitary endeavors, solitary passions. However, there are exceptional moments when one finds a speaker. Conversations become mental adventures, and these adventures come with a risk unfamiliar to the man of action. To hunt an idea or fight with a concept is no less thrilling or dangerous than fighting at a faraway border or facing a bear in a forest. In these intellectual adventures, one’s life is not at risk. One can, however, lose one’s spiritual certainness and even one’s reason. Its reward is the covenant one makes with a friend. It’s a marvelous thing to share a truth, however big or small, after one has hunted it for hours on end. The silent contemplation of the newly found mental constellations is the big reward.

Jorge Cuesta mastered those types of conversations. Sometimes he would build tall buildings made of air and light using his words and definitions. He would build reflecting buildings that would fade when someone turned the conversation. I often regretted that I didn’t have a pen or a tape recorder at hand to preserve everything he said. Some writers remain because of the work they do. Others remain because of the influence they have on the work of others. Cuesta was one of the latter. He influenced Villaurrutia, Gilberto Owen, and myself. I only met him a few times. But I think that when we were together, we often saw several truths, and I will never forget that.

You dedicated “Máscaras del alba” to José Bianco.

He was one of my best friends. In 1938, Xavier Villaurrutia had just published his fantastic book of poems, Nostalgia de la muerte. Unfortunately, it wasn’t published in Mexico. As recommended by Alfonso Reyes, Victoria Ocampo’s Argentine publishing house Sur published it instead. One afternoon at Café París, Xavier asked me to write something about his book for Sur magazine. I accepted immediately—it moved me that he might think that I, a young poet, could write something worthy about his book—and a week later, I sent the piece I had written to José Bianco, Sur’s secretary. Less than a month later, I received a letter with a generous check and a note from José Bianco inviting me to write for Sur. While I was a collaborator for Sur, Bianco and I wrote to each other often. We ran into each other in Paris in 1947. We both lived there for a long time, and then we saw each other in other cities.

The poem that I dedicated to Pepe (José Bianco), “Máscaras del alba,” is a vision of Venice. Not the Venice tourists visit. That poem is part of a series of nine poems. Each represents a city: Naples, Venice, Avignon, Paris, Delhi, Tokyo, Geneva, and Mexico, twice. I wrote the poems between 1948 and 1957 as I moved from my years of youth to maturity. That’s why I called that series of poems La estación violenta (Violent Station), also inspired by Apollinaire. La estación violenta is two times violent: first for what happened during those years and second for the accidents of my personal life. “Máscaras del alba” (Mask of dawn) is a succession of nocturnal scenes and a poetic montage; I’m indebted to film and Eliot’s poetry for that poem. At the beginning of the poem, I write about Piazza San Marco at night as if it were a chessboard, where the stars play a strange chess match: “The empty game, yesterday’s war of angels!” (translated by Muriel Rukeyser) That phrase serves as the poem’s spiritual anchor. It challenges the modern and rational vision of the fate of men (“The empty game”) and the traditional and theological vision of the West (“yesterday’s war of angels!”). Right away, as if in a film, we see a series of images from modern life, some dramatic, others ordinary; together, they form a group of disjointed moments and passions. “Máscaras del alba” is a black poem, like many I wrote during those years, immediately after the physical and spiritual devastations of World War II. I think that beyond its vague merit, there aren’t many poems like “Máscaras del alba” in modern poetry written in Spanish.

Why did I dedicate this poem to Bianco? First, because we were friends. Also, because the poem has elements worthy of a novel which, I think, might have appealed to him. A ghostly Venice looked like the black-and-white film of a talkie. Pepe liked playing with ghosts and becoming one himself, like in his novel La pérdida del reino. With him, I walked, again and again, the old streets of Paris during nightfall or right before dawn. Together we went to Ermenoville Park, in honor of Rousseau, and we looked at its melancholic pond and its limp willows. Not far from the park, and lead by Nerval’s shadow, we walked across Sylvie’s country and spent a night at an inn at Mortefontaine. We saw the night wind shaking imaginary fronds, black and green fronds. We saw the night wind rousing a light, a fatuous fire. Was it Sylvie’s ghost or Aurélia’s?

The last time I saw Pepe was in Buenos Aires, not long before he died. I told him that among my most treasured possessions were a first edition of his novel Las ratas, which he dedicated to me, and also a first edition of Borges’ El jardín de los senderos que se bifurcan (The Garden of Forking Paths), which is, by the way, Borges’ first book of short stories. The last night we were in Buenos Aires, my wife and I had dinner with him in our hotel. When we said goodbye, he gave me another of Borges’ books. He said, “Octavio, I give you this book which you love as much as I do. Georgie (Borges) gave it to me many years ago, and he wrote a lovely letter in it. I know that I will not see you again. Now you must keep it. It belongs to you, too.” I was lost for words. I smiled a feeble smile, and we hugged.

You dedicated “Entre la Piedra y la flor”—which you wrote in Mérida, in 1937, and revised in Mexico, in 1976—to Teodoro Césarman.

Teodoro is a wonderful cardiologist and a secular saint. No, he’s not a saint. He’s just, as people called men a long time ago, and just men are also merciful. I couldn’t find a better way to manifest my friendship and gratitude towards Teodoro Césarman than by dedicating that poem to him. It’s a poem that’s suddenly current today. What happened in Chiapas has made Indigenous issues a topic of conversation again. When I was a kid and a teenager, I felt close to the Indigenous world and its duality in us. I felt close to their culture and their history, and their reality. Ireneo Paz, my grandfather, wrote the first Mexican novel based on Indigenous issues, and one could find countless books and chronicles about Mexico’s ancient history in his library. I skimmed those books. I read some of those books. I was amazed by the artwork of those books. Thanks to that, I became a fan of anthropology and archeology. Plus, my father had joined the Zapatistas, and he later was one of the founding fathers of the Agrarian National Party, along with Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, Aurelio Manrique, and others. Peasants regularly visited my house, and since my father was a lawyer, he would help them with any issues they had with their land.

In 1937, I was in Yucatán, and I saw first-hand the reality of Indigenous peoples in Mexico, the reality of their cultures (the Mayas in this case), and the hardships they faced every day. Life for the Mayas in Yucatán then revolved around the henequen. The henequen industry in 1937 was, as I remember, fading out—first because of competition and second because technology had displaced henequen from the world market. I was shocked by the fact that the slave-dependent henequen industry coincided with the contemporary international market. This framed the peasants’ reality. They were the heirs of an ancient civilization and were then transformed into employees to be alienated further. President Cárdenas’s agrarian reform did not improve their life. The old landowners were substituted by government banks and political bureaucracy. The agrarian reform was a late and insufficient remedy. Henequen stood no chance against newer industries.

I wanted to write a poem based on that reality, and I wanted that poem to be based on history and spirituality, and a mix between eras and cultures. I remembered Eliot’s The Waste Land and how it shocked me when I read it. I wrote different versions of “Entre la Piedra y la flor.” I was never satisfied. Anyway, I think that at least I did manage to convey many of the things I wanted to say in that poem. Number one: Yucatán’s landscape. Number two: a viewpoint about Indigenous people devoid of sentimentality or ideology and far from superficial realism or didacticism. It’s a viewpoint—and I say this not trying to be arrogant—with a bit of human truth and poetic truth. I also tried to show the strange relationship between the traditional Indigenous society and the brutal reality of money—the modern god.

My Yucatec poem makes me think of a topic I’ve addressed occasionally. I was always passionate about the “subterranean Mexico,” as I call the Indigenous world. I have written countless essays and even a short book about Mesoamerican art. Those texts are not just speculations about aesthetics but deep analyses of pre-Columbian Indigenous cultures. Plus, ever since I wrote El laberinto de la soledad, I’ve been interested in the nuances and what it means to have the Indigenous world present in modern Mexico. [Guillermo] Bonfil, a renowned anthropologist who recently went missing, wrote about this matter and called his dissertation México profundo; it is a well-intentioned yet questionable text. Naturally, this is not the time to analyze these chimeric ideas. I will add a thing or two. The title of Bonfil’s book, México profundo (A Deep Mexico), seems to argue that there’s a civilization still alive today that cohabits with Western civilization, yet is oppressed and hidden by it. To Bonfil, the Indigenous world is Mexico’s deep reality, and modern Mexico, starting in the sixteenth century, hides the Indigenous world. According to this argument, the Mexico we all know and have been living in for the past five centuries is a superficial Mexico, be it our history or our buildings, be it the temples or the ideas, be it the laboratories and the laws that govern us, be it the schools that teach us or the jails that punish us, though not always justly; be it the poems and novels we read or the family based on monogamy and from which we come: all superficial.

First things first: a civilization is a group of institutions, tools, social classes, gods, techniques, buildings, philosophies. A civilization is an all-encompassing and coherent being. Let’s be honest: the Mesoamerican civilization was destroyed, and whatever’s left of it are fragments that are scattered, admirable and revered ruins, and all are devoid of a common place that might feed and inspire them. History does not return. A Mesoamerican civilization is like the monuments it has left behind and that our archeologists bravely try to rebuild and restore. They rebuild these monuments not to turn them again into sanctuaries teeming with the life of a collective faith, but to transform them into objects of aesthetic contemplation or worthy of historical and anthropological research. Additionally, the customs, arts and cultures of today’s Indigenous communities are a mixture of several cultures from different times and ages. It couldn’t have been otherwise. They are the result of history.

A clear example of all of this is Chiapas. The religion of the Indigenous communities in Chiapas is a mixture between Catholicism—in the way it arrived on this land in the sixteenth century—and many other modern religions and traditions, including liberation theology, set to a pre-Columbian polytheistic background. Other communities have embraced various versions of Protestantism—right at the beginning of modernity. To sum up, as far as religion goes, today’s Indigenous culture results from a complex mixture of elements. This is an example, among others, of the cultural miscegenation that’s so characteristic of our country. The same thing happens in other aspects of their culture: property, agricultural techniques, craftsmanship, popular arts, sexual morality, politics, etc. Miscegenation is the basis of Mexico’s reality today. Let’s not forget that in this miscegenation, society’s basic institutions are predominantly of Western origin: democracy, the republic, religion, science, technique, art, family, etc.

Miscegenation, syncretism, acculturation can be considered forms of translation if we think of it not just as the path from one language to another, but of the transmutation which radically changes the original text. Our Lady of Guadalupe is a direct transmutation of pre-Columbian feminine divinities such as Extremadura’s Our Lady of Guadalupe and other characters that belong to the Mediterranean’s religious tradition, as proven by Jacques Lasaye. This topic takes us to another issue of interest today. When people talk about being respectful to the Indigenous communities’ cultural and political autonomy, do they want to go back to the way things were during the pre-Columbian era? Or do people want to translate contemporary Indigenous tradition—syncretistic and a result of miscegenation—into modern times? The first would result in stagnation and petrification. The second would result in the recreation and transmutation of the past. Do people want to separate the Indigenous peoples from other Mexicans and doom them to a loneliness that has no way out? Mexico’s future and originality lie in translation-transmutation. This translation began in the sixteenth century and is the basis of our historic physiognomy.

Shall we continue with the inscriptions?

There are too many, and we don’t have the time or space to talk about them all. However, one is missing. The most important of them all. I dedicate all my work to my wife, María José. To forget about her would be to forget about the sun when talking about the light of the day.

In an interview you gave twenty-four years ago, the last question they asked you went something like this: “What do you want to do with the future?” and you said, “Abolish it.” Did you do it?

Future is part of the structure of human beings. Men are time. We are made of time. We are past and future. My answer was aimed at how people revere the future and the superstition of the modern man who sees paradise when looking into tomorrow. Our mission is not to conquer that paradise, which is located in an unreachable place—unreachable by definition; our mission goes beyond that. The future is untouchable, ungraspable. Our task is to make the present habitable. In that regard, and without fully achieving it, I have made an effort to abolish the future.