It’s February and I’m counting swimming pools. I navigate with Google Earth over the geography of Cabo de Palos and count swimming pools. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven . . . until I lose count. I examine their shapes (curved, rectilinear, mixed), their shades of blue. I bathe my pupils in each of them. It relaxes me, refreshes me, makes me feel like I’m on holiday even though it’s cold here. Google Earth has made possible a new twenty-first-century tourism. I think I could spend hours (in fact I often do) roaming over the surface of the Earth. Google Earth has granted us the perspective of an astronaut, of a space flaneur. It’s better than having a time-share. It’s better, even, than being God.

Nearly all of the pools are empty, but if I zoom in close enough I can make out objects floating in the water of some of them. A yellow float. The figure of someone swimming . . . and a boat. A small sailboat floating in a pool. Why on earth would anyone decide to put a boat in a swimming pool? I imagine the owners fishing, sitting on the deck, waiting for a bite from one of the fish they’ve bred in their waters. I return to the human figure. A man with a paunch (to be a man is, above all, to have a paunch), a teenage girl . . . I zoom in more. It’s a woman. I am God, and I give her a name: Eve. She doesn’t know I’m watching her. I like her swimming pool. I like her bikini. I fall in love with the handful of pixels that compose her figure. I know where you live, Eve. I could go and pay you a visit. I could buy an apartment in your building development and, so doing, become your neighbor. Except, in truth, I can’t. I don’t have the money for that. I feel an overwhelming urge to rob a bank so I can buy that apartment and go down to that pool when you’re in it and swim over to you and embrace you. You would tell me about your husband who doesn’t love you like he used to, about the sirocco that scorches the lawn and turns the swimming pool into one of those cauldrons where the people condemned to hell suffer. Condemned to go insane. And I would understand you. I would tell you the story of a man who assembles a piece of IKEA furniture and during the night tosses and turns in bed unable to fall asleep because he knows something has gone wrong, one of the assembly steps, and then he secretly gets up in the early hours of the morning, trying not to wake his family, and checks the instructions with a flashlight and manages to fix the mistake and goes back to bed, calm at last, at peace with the god of DIY. You would laugh, and that would make me happy. I want to know more about this man, you would say. And I would reply that his story is sad. No more than mine, you would say. And she would tell me about those days when no one responds to her Facebook posts, so she makes a purchase, a bottle of wine, a book that doesn’t even interest her much, and impatiently awaits the arrival of the confirmation message to feel, for the first time that day, that she isn’t alone in the world. What contemporary madness, I would reply. Think of a convex beach, I would say, a beach like the prow of a ship heading out to sea. Impossible, she would reply. And what about the laws of nature? We live surrounded by the impossible. The impossible is what exists. It’s only a matter of time before the impossible becomes both routine and ruin (perhaps in the end they are the same). Man walks over the impossible but breathes thanks to the possible. Dreams are the literature of the species rendered hardware. Before we knew how to speak or write, dreams brought us face to face with the possible. We are lucky. Only animals can be content with the impossible. For them (animals), everything, in fact, is impossible. Now I must leave. I can only appear for brief moments. It’s not that I’m an omniscient narrator, don’t get confused. It’s just that I must return to reality, to the impossible. Because, to my regret, I am also impossible. It’s my nature. It is I, your creator, who must depart while you remain in the paradise of possibility.

Next I fly to Benidorm and explore Levante Beach. I see the umbrellas, the bathers lying on their towels (they look like corpses, tanned bodies surprised by a sudden apocalypse), children building sand castles. I see a young man looking up. He scans the sky. He’s watching a seagull, or perhaps he senses that someone is watching him. It’s me (I wave). I imagine the front rows occupied by the elderly, as if the sea were an obscure metaphor for death and they were waiting their turn there. I imagine the multicolored line formed by these umbrellas, stretching along the thousands of kilometers of the peninsula’s coast, from Girona to Euskadi. This line forms part of a topology of desire. That disputed first meter of beach lapped by the waves, like a river strewn with gold nuggets. I imagine that all those sexagenarians form a line of protection, that if it weren’t for them the sea would invade the land, would destroy the Torre de Hércules, La Manga del Mar Menor, Las Ramblas, La Gran Vía, La Giralda, the Meseta Central, and that magnificent void that is Soria, including Machado’s elm; that they are the ones who protect us and keep us from the fury of the sea. Effectively, all those colorful umbrellas are the skin cells (fragile and ulcerous) of a body that resembles the stretched-out skin of a bull. A body that cools its fever in the sea, a body that would implode without the therapeutic envelopment of the ocean.

Now I imagine that someone, using Google Earth, discovers a strange spot in a park. He zooms in and discovers that it’s a man lying on the grass. Next to him he can see a pool of blood. It is in fact a corpse. A few meters away, the figure of another man can be seen, about to disappear into the trees. Probably his killer. Not far from the scene is a playground. Children are playing, oblivious to the event that has just occurred. Only the satellite image has been able to capture the crime.

Cameras can see things that the human eye is incapable of perceiving. The camera lens was Lacan’s favorite metaphor for referring to the big other. This is the idea that lies behind Dziga Vertov’s conception of cinema. This is what Barthes calls the optical unconscious, the same idea on which Cortázar’s “Las Babas del Diablo” (and its cinematic counterpart Blow-Up, by Antonioni) is structured, as well as Fleur Jaeggy’s story “The Black Lace Veil.” It is Pedro’s obsession in Arrebato, Iván Zulueta’s film.

The photographer-nanny Vivian Maier, after reading about the crime in the newspaper, photographed the supermarket and the exterior of the house where a woman who was murdered, along with her son, lived and worked. Vivian Maier was unconsciously guided by the same idea, that the camera would be able to reveal the culprit of that crime. It’s an absurdity, almost a superstition, to equate the lens of a camera with the privileged vision of a god. The symptom of a religion that is gaining new followers by the day. Marcel Broodthaers’s “The Watching Camera” could be the totem around which we perform our late-modern aboriginal dance.

Next I look for the photo of Borges in which the writer appears disguised in a Big Bad Wolf mask. I find it without difficulty. Borges looks like a real monster. The mask is so realistic that those who behold it get the impression that they are confronting a real Wolf Man. A Wolf Man wearing a suit and tie, which makes it even more disconcerting. My impression is that I’m not seeing Borges disguised as the Wolf Man, rather that the image has captured the Wolf Man disguised as Borges, a way of being able to eat the little red riding hoods of poetry, the little pigs of literature.

I’ve always been reluctant to put on disguises. I could give a thousand intellectual arguments, but I don’t feel like seeking excuses. An exaggerated sense of the ridiculous, maybe that’s it. Although now that I think about it, and changing my mind (since I’m not a river, I can reverse course whenever I feel like it, a teacher from my childhood used to say, this simple wisdom being enough for me to remember her fondly by), I think I don’t like wearing disguises because, being a pure exhibitionist, I have nothing to hide, so why don a mask if the only thing I’d achieve would be to evade the gaze of others, violating my nature? Nevertheless, there is something fascinating about Borges’s mask. I have always found Borges’s work fascinating, and now I find myself being seduced by his mask. Borges is a kind of sorcerer who has me under his spell, even after his death (although writers, especially the good ones, are always a bit dead). For someone so little given to mythomania as I am, it’s a mystery. But every rule has an exception. I find myself searching the internet for Wolf Man masks. Not any old one, but the one Borges is wearing in the photograph taken of him at his home on Calle Tucumán. My eyes scan hundreds of images of Wolf Man masks. Apparently the first time Borges wore the mask was at a Halloween party during a residency in the United States. I deduce that the mask must have come from somewhere in North America. After an hour of intense searching, I think I’ve finally found it. As I make the online purchase I’m overcome by a feeling of unmitigated euphoria. I buy it. I can’t wait to put on that mask and sit down to write and stroll through the forest of literature with my brand-new Wolf Man mask, to see who I stumble upon, to scare them, and, perhaps, to wolf them down.

While I’m waiting for it to arrive, I think about what I’m going to write. I’m not talking about at this precise moment, but from now on. It’s a question that delves not so much into the next move as into the nature of the game itself. About people (I answer myself), but, above all, about things. It’s about ecology, about respect for all the matter that surrounds us. We worry enough about people and animals, but what about things? We stockpile them on shelves in supermarkets and department stores like prisoners lined up behind the bars of their cells. We use them as if they were people and then throw them away. It’s not just. It’s not democratic. Why limit oneself to people when you can narrate the world in all its multiplicity? This world will be neither just nor democratic until we liberate things from the yoke that we ourselves impose on them. We need to set them before us and meditate on them, to reveal the potential they conceal within.

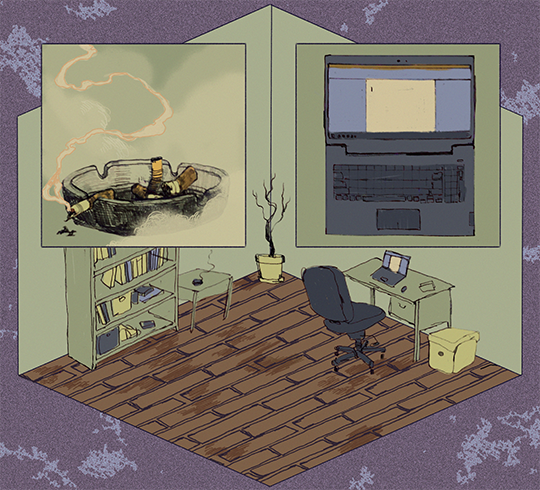

I look around me, searching the solitude of the room for understanding from the objects that surround me. I find it in the little Nazari table, in the ashtray full of cigarette butts, and in the tiny spiderweb on the ceiling. There flows between us a common current of contingency, and at the same time the joy of existence, of absurdity in the face of the vast dimensions of the stars. Our voids meet their abysses in perfect reciprocity. I appreciate the desire of each of them to be something else, to be on the verge of achieving it. If they don’t move, it’s out of shame, and out of respect for the domesticity we agreed to long ago. Like me and that Wolf Man mask. I will rescue it from an Amazon warehouse and make it feel important, I will bring it to life in a story, in the one I’m telling.

Matter is energy, of course, but it’s also poetry. It’s a matter of knowing how to use the right tool.

Sitting down to write is somewhat like making an appointment with yourself, to tell yourself a story using your own mask, or one from a more or less extensive collection. It can seem paradoxical, this business of meeting yourself at the keyboard, to observe yourself in the screen as if in a distorting mirror. But sometimes you part ways with yourself and someone else shows up, and that’s when things get interesting and a spark comes to your fingertips from who knows where.

The things around us are continually ‘happening.’ Not being, but acting. They maintain a dialogue made of colors, energy, and textures. The script has no restrictions, except those imposed by the stage itself. There is the coffee cup actress (gleaming whiteness), the Nazari table actress (geometry lesson), the money plant actor (phototropic addiction), the ashtray actor (embalmer of breaths), the PC actor (astonishing Aleph), the CD player actor (meek madness) . . . I’m attached to each of them by varying degrees of affection. I hold all of them in the same regard. I like to think that I’m part of the show, that they don’t play their role for me but that I’m part of the scene. And the role that has fallen to me is to accompany them for as long as my life lasts, to bear witness to their transformation. Before I leave I hope I’ve left something in them. Things (the vast majority of them, at least) will outlive us. They are part of our legacy. They are our heirs. The paradise in which we will be saved, or the hell to which we will be condemned, is embodied in things.

Before leaving the job, I could go days without writing a single line. Writing was a compensatory appendage to my work life, an organ that provided excitement on a regular basis, little more than that. Now an hour without writing, let alone a day, weighs on my conscience like a stone slab. I try to stick to a schedule (nine to eleven, a break for shopping and coffee, and a second shift from twelve to two), but I end up breaking it on the slightest pretext. I’ve always been a writer of impulsive bursts, of rather ephemeral creative raptures. My literature is basically an accumulation of intensities, incompatible with an office schedule.

I’m a writer of brief, intense efforts, a sprinter who arrives defeated at the finish line of the end of a paragraph.

In fact, it happens that in the moments of greatest literary effusiveness, when one knows he is doing well, the instant in which the craftsman finds both the greatest pleasure and the maximum dissolution in his work, in those moments something incites me without any logic to abandon writing and devote myself to who knows what activity, searching for an invoice or looking at shoes on the internet or opening my Facebook account or sharpening my pencils. It’s an incomprehensible act, lacking any explanation. Like a tightrope walker who decides to stop and contemplate the landscape before taking the last step over the abyss. It is, perhaps, the delectatio morosa, that delaying of the satisfaction of desire, of postponing it precisely so that it doesn’t reach its fulfillment and, along with it, the return to longing, the starting line of the circle of desire. We are an arrow aimed at the bullseye. We know that we’re heading in the right direction and that we won’t miss our target. So why not try to extend the time we have left until the moment of impact, like one of those paradoxes that the man from Elea was so fond of?

After glancing at my outstretched fingers I decide to cut my nails.

Although I’m right-handed, the thumbnail on my right hand grows faster than the one on my left. This isn’t true of the rest of my fingernails. Only the thumb. Perhaps it’s an encrypted message in my genetic code. Maybe I missed my calling as a guitarist. Then I remember that graphein is the word the Greeks use for writing, and that it comes directly from the Indo-European gerbh: to scratch, to scrape. That writing consists of scratching a surface (sand, wax, stone, clay) to inscribe signs in it; but, also, that it is necessary to scratch that which surrounds us in order to chip it away and peek into the magma hidden beneath the polished surface of things, and that this, perhaps, is the deepest meaning that lies behind writing. Or simply scratching (writing) to defend ourselves, to survive the threat looming over us. Writing can be an active and/or a passive exercise, an attack but also a defense.

The foregoing is beautiful reasoning, lacking in reality like most thoughts, but beautiful. A lovely justification for wallowing in laziness and not cutting my nails. Words may not capture the truth, but they are an ideal palliative for accommodating oneself to the mere facticity of what is happening.

I end up doing it in the end, though. Cutting my nails. All before facing the story, the document that demands my attention on the screen, the characters and the plot. Then I think that nails also deserve their own literature. In fact I record a video of me cutting them. A close-up of my hands and the small curved-tipped scissors slicing perfect lunules. Afterwards I post it on my Facebook profile. Someone said of Goethe that he was refined even while cutting his nails. That seems a splendid tribute. I want to see if any of my friends feel the same way when they see my manicure scene.

I should start writing (I’m already an hour late), but I don’t feel like it. In fact I find myself in one of those moments of disaffection with my own work. This happens to me all the time, but it doesn’t prevent me from feeling, time after time, that I’m a mediocrity, that what I have on my hands is a fiasco, a waste of time, a real piece of garbage. Then time passes and everything falls into place. But this stage is always too long and full of uncertainties. You have to tie yourself to the mast and resist the temptation to throw it all overboard. My main character still seems feeble to me. I know it’s normal, that characters are seedlings, that they need time to gain muscle and psychology, but I’m impatient by nature. I’ve killed a lot of plants by scratching in the soil to see if the seed has germinated. I’ve abandoned the construction of a lot of characters who have barely stammered their first word. The very word, ‘character’ (personaje), is annoying to me, like a debased double of the word person. That suffixed je that sounds like a bad joke. More than a suffix, a clown’s nose or a cancer.

It takes a year or two, sometimes even five or eight, to write a book. There are seasonal works and generational works. A novel can grow like a field of wheat or like a shrub clinging to the earth, too slow in either case for this growth to become a spectacle. Who has the patience to watch the movement of a glacier or the spiking of a wheat stalk? Literature is like that tree we only notice when it bears fruit.

I decide to wash the breakfast dishes. Scrubbing is good. It’s relaxing. With your hands wet and lathered with suds, you can let your imagination run wild. That’s the beauty of routine, performing an activity that occupies an infinitesimal part of your brain. There’s nothing like mastering a skill to allow the creative part of your brain to feel at ease. Only a total mastery of technique can give rise to that state of grace we call talent. I think at least a third of my literature (whatever good there may be in it) has germinated in these seemingly inconsequential moments: scrubbing, taking a shower, trimming my beard, or peeling potatoes. That’s why you should write like you shave or wash a dish, with the same nonchalance, so that the remaining ninety-nine percent of your brain can open up to the world and connect with really important things.

Man has achieved verticality by walking, and horizontality by means of his erection. Part of his anatomical perfection lies in this adherence to the right angle.

I leave the plate in the drainer and rush back to my post in front of the computer to write down that thought, before it returns to the subconscious from whence it came.

Xavier de Maistre believed that it was in these seemingly inconsequential moments that the soul withdrew from the beast that we are, to fly over the world and converse with the angelic powers. Thomas Alva Edison said that his work consisted of one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration. I believe, at least in the case of creation, that it’s the complete opposite, a tiny percentage that is routine and mechanical (typing, aiming for a standard use of language, breathing, imagining that someone will someday read what you are writing) and a vast unfathomable iceberg, a forest where you lose yourself in order to find (or not) the way.

I’m a man who scrubs, who cooks, and who writes. I also fuck, although that activity is currently in parentheses. I wonder how many things a man can do and still be considered a man. Or, conversely, how many he can stop doing. It’s like the joke about the spider whose legs are being cut off.

I receive a call from Giulia, my literary agent. She asks me how everything is going. I tell her fine. And how is her family? (She just became a mother for the second time.) I know she wants to talk about my novel project, but I don’t feel like it. She promptly snaps me out of my funk. She called me to recommend a magnificent Borges exhibition at La Casa de América. She was there last week. Why didn’t you call me, I ask. She replies that it was a whirlwind visit. Literary agents are rather like intelligence agents (in fact, they really are intelligence agents in the sense that they are constantly talking to intelligent men and women, trying to bring that intelligence to other languages), always in transit from one country to another, from one coffee table to another. She says there is first-rate material in this exhibition (she knows my weakness for the Argentine author). A photo, for example, in which Borges appears disguised as Wolf Man. Borges and the Big Bad Wolf. A metaphor that takes me a few moments to digest, like one of those disconcerting culinary creations whose fusion of ingredients seems suspicious to the intelligence but to which our palate nevertheless surrenders unreservedly. Yes, I’ll go see it, I reply. She seems pleased by my acceptance of her proposal. Perhaps Giulia is even more intelligent than I suppose and she’s trying in a sibylline manner to introduce variables in my mind that will only be resolved in a novel or a poem. We bid each other farewell until the next time.

I check my Facebook profile. On my post with the video, there is a solitary ‘like’ next to numerous emoticons expressing astonishment, sadness, and, above all, disgust.

I’m still a long way from becoming Goethe.

The doorbell snaps me out of my thoughts. It’s probably the courier. I open the door and, sure enough, there he is, with the package in his hands. Amazon is evil incarnate. Like evil, it is fast, omnipresent, and impossible to defeat. I open the cardboard box. It’s my mask. I put it on in front of the mirror. We look terrifying. Together we make for an explosive combination. We return, my mask and I, to the keyboard. We howl, and I feel the spiderweb, the Nazari table, and the ashtray shudder around me. I know what they’re thinking. If I can be something else then so can they, they seem to be saying. They plot the change of their acts. The table shines brighter in response to the light penetrating through the windows. The spiderweb yearns to be a harp. The ash is no longer an indistinct mass of dust but an accumulation of desiccated moths. My lungs harbor the dust from their wings.

Gradually the things settle down. I take the mask off to observe the objects having their siesta around me, emitting pulsating waves, transmitting an imperceptible message, like soundless cicadas under the blazing sun.

But it’s not just the objects. In fact, emotions can be as objective as the things around us. Noticing this consists of standing on the other side of our skin and contemplating from there the landscape of our feelings, the seed from which our thoughts (though perhaps it’s inappropriate to call them ours, just as the trees, the birds, and the buildings on the other side of the window aren’t ours) sprout.

If I look for the protagonist of the story of my life, then I see nothing but a disjointed succession of things and people. The story of my life is absolutely democratic and, therefore, I suppose, can no longer be considered a story but rather a tailor’s drawer (an expression that, by the way, as far it concerns me, lacks a referent—I have never in my life been on friendly enough terms with a tailor for him to show me his drawer—although I suppose it must be so, that the image that sums up the story of my life must be something that is excluded from the story itself, otherwise the image would be endowed with an undeserved prominence, or at least as deserving as the rest of the beings who have passed through it, and all of this would make of my life a paradox in which the defined entered into the definition, what a mess), a tailor’s drawer where all the objects contained in it are endowed with the same value, like one of those Chinese markets where one can buy all manner of products for the same price. It’s a story, therefore, devoid of events, and it’s possible that the others, the people I surround myself with, sense something and therefore hold a preemptive grudge against me, because no one likes to be equated with a vase or an oak leaf. But at the moment when I, the narrator of my existence, endow that vase or that leaf with an inordinate interest, this resentment is unfounded from any perspective. The problem lies rather in people and their sense of superiority towards all other beings (and this includes other people), but that is their problem, not mine, nor that of the vase or the leaf; and if any amazement attends this way of seeing things, it is that of witnessing an act of true democracy. Because democracy, like all absolutes, is scary. Everyone longs for that minute of glory that they would gladly take with them to the next world, and, in fact, they all get it, that minute. What happens is that this minute must be shared with the cup of coffee in their hands or the earrings or the dress (ah, that dress), because in reality they aren’t the exclusive protagonists of the scene, and sometimes it’s their voice or their clumsiness or their fame (yes, sometimes I let myself be dazzled by the tinsel), but I also let myself be duped by the utmost insignificance and triviality and frivolity, and all with a supreme lack of discretion, or rather I let myself be carried away by the sole consideration that everything in this world could be equally marvelous and, of course, exceptional, and when one is a true democrat with all beings, then one can sleep peacefully. Insignificance is the dust raised by the horseman in the epic, the fly perched on the pistol that appears in the scene and that no one shoots. Behind my consciousness lurks a filmmaker, a Franciscan documentarian specializing in minutiae who thinks that framing and lighting are everything when it comes to achieving poetic glory.

I once saw a seagull attacking a drone. It was on the Benidorm beach.